Over the Pyrenees

September 11-13, 1940

During my first week as a courier, I was constantly on the run between the ERC’s office and Marseille’s central post office sending coded telegrams to New York. I went from one tabac (government-licensed tobacco store) to the next buying blank identity cards and taking them to a person staying at the Hôtel de l’Espérance (Hotel of Hope!) under the pseudonym Bill Freier. The blanks were official forms for the identity cards everyone in unoccupied France had to carry. One filled them out and took them to the police to be stamped. Of course, many of the refugees under the Vichy regime had no official status, so the stamp had to be forged. Freier was a master forger.

I remember having seen him before I joined the ERC, sitting in front of a fancy restaurant on the old harbor drawing caricatures of people for ten francs a picture. They were so artfully and skillfully done that I would have had him draw one of me had I had the money. Freier was using his skills to forge documents for Fry: Vichy identification cards complete with a police stamp and the signature of the “Commissaire de Police” flawlessly executed.

The first time I was on this mission, realizing that I carried a bunch of fakes with me, I kept looking over my shoulder to make sure I wasn’t being followed. Just to be on the safe side, before going back to the ERC office, I darted into a big department store with many entrances and exits, ran out again, and jumped onto a bus just as it drove off, a maneuver I’d seen in spy movies.

My first truly dangerous mission was undertaken in the second week of September 1940 when Fry asked me to meet him and one of his trusted assistants, Leon Ball, at 4:30am inside St. Charles Station. When I arrived, he and Leon were talking to two elderly couples surrounded by a mountain of suitcases. Fry was in a state of great agitation, gesticulating and walking back and forth in front of the people he was talking to. His behavior struck me as rather odd and very much in contrast to the subdued manner of the circumspect person I knew in the office.

While Fry went to the ticket window, Ball took me aside and told me that all of us would be boarding the train to Cerbère, a French town close to the Spanish border, and that I would be in charge of the baggage. From identification tags on the valises, I could tell that eight of them belonged to a Mr. and Mrs. Mahler/Werfel. Could it be, I wondered, Franz Werfel, the author of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, a novel that dealt with the genocide of the Armenians by the Turks during World War I and that had brought him world fame? The lady next to him must have been his wife, Alma, a celebrity in her own right, the widow of the composer Gustav Mahler and later of Walter Gropius.

There was an irony in these particular exiles’ situation, for they were people, it turned out, who had made their living by what they wrote on pieces of paper.The other suitcases belonged to Mr. and Mrs. Heinrich Mann, another name familiar to me as Heinrich was the author of several novels, in particular Professor Unrat, whose film adaptation known as The Blue Angel I saw that night with Elisabeth. Our task on this adventure would be to get all these people across the Spanish border. Though the Fascists had won their civil war with the help of the Germans and were more or less their allies, they were not obstructing French refugees from entering Spain as they attempted to leave Europe. Generally the French required one to have an exit visa to depart from France, but if you could get across the border without one, the Spanish as a rule would not send you back, though this was not always the case and what would actually happen varied from day to day. But the main obstacle in our adventure was that, except for Fry himself, none of us had exit visas.

By the time Fry returned with the train tickets, Golo Mann, Heinrich’s nephew (and Thomas Mann’s son) had joined us. Fry pointed to the mountain of valises and said, “Make sure that these bags get on and off the train with no problems.”

At precisely 5:30 am, the locomotive pulled out of the station into the panorama of Provence, still under the blackness of predawn. Two hours later at Nîmes two gendarmes came aboard to check the passengers’ papers. Traveling to the border without a special permit or French exit visa could lead to arrest.

They walked right past our first-class compartment. They must have thought that such distinguished-looking elderly people and their relatives would not be traveling without proper permits. With the gendarmes gone, the Manns, the Werfels, and Golo, who had Spanish, Portuguese, and US visas but no French ones, were still anxious. Fry calmed their apprehension, saying that his plan would enable them to travel directly from France to Spain without impediments. “Upon reaching Cerbère,” he said, “we have to get off the train to catch a connection to Portbou on another platform. To do this, you must go through a restaurant that exists between the platforms, to avoid having to pass through Passport Control.”

At the station at Cerbère, we all sat down in the restaurant, while Fry and Ball went out the other door to try out the stratagem, but they were stopped by customs officials. Only Fry was en regle (had proper papers) and could get to the train. They wouldn’t let Ball through. They came back to the restaurant.

Ball now took charge of the situation, gathering everybody’s passports and disappearing into the office where the officer in charge was sitting, but he soon came out again, looking rather glum. The border guard had strict orders: no exit visa, no boarding the Portbou train. Ball persuaded the officers to keep the passports—to ensure that we weren’t going anywhere— and allow us to find a hotel and stay overnight while the matter of our papers was straightened out.

Fry placed three possibilities before us: we could return as far as Perpignan (a large town about 30 miles away) and try to secure exit visas; Fry could do that while we waited in Cerbère; or we could cross the Pyrenees on foot and land in Spain.

I must say the whole operation seemed a little strange to me and still does so. What was Fry’s actual concern in getting these important people out of France? Why did he give them so much priority that he himself was accompanying them? I think it was because he wanted to show the people in New York his competence and that he was willing to take the risk. He was anxious, but also invigorated. If things misfired, he would be responsible for the arrest and internment of the people depending upon him, but as a matter of fact, the risk wasn’t actually his! The US still had diplomatic relations with both Vichy and the Germans. But if he pulled it off, it would be by the grace of his decisiveness and daring.

There were many practical matters involved in getting people safely out of France . . . . It seems I was to be a spear-carrier in the struggle for freedom.There was an irony in these particular exiles’ situation, for they were people, it turned out, who had made their living by what they wrote on pieces of paper. They were famous authors and their wives. Now suddenly their lives depended on what others wrote: Fry’s “list”; false names and fake passports; a primitive border map; the blue writing on visas; and instructions communicated by brief and enigmatic telegrams.

We agreed that the refugees should trek over the mountains. The distance to Portbou was about five miles as the crow flies, but it involved a very difficult climb over rough terrain up the Pyrenees and down. It was especially difficult for the elderly people in our party. Ball and I would go along to assist them, and Fry would travel with the luggage to Spain and meet them at Portbou. Now I had to make sure that the luggage went along with him. Fry downplayed the difficulty of the passage across the mountains, though it should have been clear that the aging couples would have no easy time of it. Werfel was a short, plump man with a pear-shaped body and bottle-bottomed glasses, and soon had trouble keeping up with the purposeful stride of the imperious woman—Alma Mahler—at his side. Eventually she and Ball had to prop him up to get him over the mountains. Heinrich’s wife and I, in turn, helped Heinrich.

During our long forced march—a hike that would normally take two hours took us six—I got to know Nelly Mann pretty well. She was a relaxed and jovial woman, even under these trying circumstances, and was very happy to have someone with whom to talk German. Every so often she discreetly pulled out a small flask of brandy, took a swig, and offered it to me. She told me her maiden name was Kröger and that she had married Heinrich—who was now seventy years old—only ten years before, though they had been together since the 20s when as a young cabaret dancer she met him.

She was now just 41. From the mountaintop we could see Portbou below, directly adjacent to the Spanish border. As soon as they arrived at the border and made it across, they would have to register and show their Spanish transit visas. Once their passports were stamped, they would be free to take the first train to Barcelona, and from there to Madrid and Lisbon. All this happened without any further difficulties. Fry went with them, Ball and I boarded a train, I to Marseille, Ball to other projects.

On the ride back I gave some thought to what I was doing at the American Emergency Rescue Committee. There were many practical matters involved in getting people safely out of France. It required a lot of money, a lot of planning, and a lot of people to carry out the tasks that made rescue possible. I think of these people as the spear-carriers in an army. It seems I was to be a spear-carrier in the struggle for freedom.

*

Walter Benjamin

Late September 1940

When I got back to the ERC office on September 13, since I was the first returning from what was in fact a test run across the Pyrenees, everyone in the office was relieved to see me and wanted me to tell them of my experience. Two weeks later the place was abuzz with the story of another attempt to get refugees across the Pyrenees, this one not quite as successful as ours. The ERC, it turned out, was not the only group involved in this line of work. Hans and Lisa Fittko, as private individuals, had established themselves in a pension at Port-Vendres near Portbou and were helping refugees, intellectuals, artists, and anti-Nazi organizers without proper exit visas leave France. Walter Benjamin had approached the Fittkos and he was part of a party on their way into Spain.

I knew nothing about this Walter Benjamin, who in fact was one of the most insightful, original, and eccentric intellectuals of the 20th century, though he struggled all his life for academic and other recognition. There had been a period when he was known as a leftist thinker among German intellectuals—a close associate of Theodor Adorno, Gersholm Scholem, Hannah Arendt, and many other important thinkers. Though his scholarship was impeccable, his views, his habits, and the sheer inventiveness of his literary manner made an academic career very difficult.

At 48, in frail health when he attempted to leave France, Benjamin was not on Fry’s famous “list” and he had not sought our help. I have often asked myself why that was so. I had once taken a peek at that list, and what I noticed was that though prominent artists and intellectuals, many of them “radical” in various senses, were on it, known left-wing political ideologues and activists were conspicuously absent. Be that as it may, he had come to Marseille seeking to leave France, where he was fairly well connected to other important intellectuals, including the novelist Arthur Koestler. His friends had succeeded in getting him visas to cross Spain, enter Portugal, and to enter the United States, where a position at the New School for Social Research awaited him. The only thing lacking was the French exit visa, which, as we have seen, was only necessary some of the time.

On the journey across the mountains, Benjamin, according to everyone who accompanied him, remained stoical and gracious in spite of the fact the man was suffering from a heart condition, depression, and general nervous fatigue. He followed a regular procedure, walking steadily for exactly ten minutes, then resting. He kept that rhythm for the whole journey.

Though he and his group made it across the border, they were stopped right in the village at Portbou where the local Spanish—not the French—authorities would not let them proceed through Spain without the French exit visa. They would be allowed to spend the night in Portbou but would then have to return to France, unless of course the rules changed. The next day the rules did change. The refugees were allowed to go on, but Benjamin had been too distraught to wait out the night and try again. A longterm drug user, he was carrying a supply of 14 morphine capsules, swallowed them all, and was found dead in the morning. It was no accidental overdose. He left a suicide note for Theodor Adorno in the hotel room.

I felt that Benjamin’s tragic death confirmed an observation I had made while trekking across the Pyrenees; namely, that especially gifted persons—what the French academy dubs “les Immortels”—have their weaknesses, temptations, fears, and doubts, just like any of us mortals. We idolize those whose innate capacity, ambition, sometimes public-mindedness, some- times necessity, sometimes rank desire—have propelled them toward achievement. There are no geniuses, really, only what people make with what they are given—that, and a confluence of circumstances. I myself have had an interesting life and a successful academic career. This is certainly partly due to my ability to learn languages with ease, but just as much to the people I met, the historical events I happened to be a part of, narrow escapes in dangerous situations, and the habit I formed of thinking seriously about what was happening along the way.

—————————————

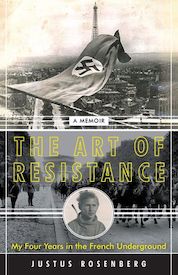

From the book, The Art of Resistance: My Four Years in the French Underground. Copyright © 2020 by Justus Rosenberg.