The Man Behind the Guns

of World War I

Nathan Gorenstein on John Moses Browning's Beginnings

in Weaponry

Nineteen-year-old Gavrilo Princip, a self-styled patriot but a terrorist to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, was a slight, dark-haired youth with a thin mustache atop his upper lip. On the morning of June 28, 1914, he slipped a small pistol into his pocket. It weighed barely more than a pound, so no saggy bulge could betray him to the Sarajevo police. The machine—and by any standard it was a finely made machine—was an expensive bit of modernity, but then Princip and his handlers were serious men. To kill the future king they’d chosen the very best tool. There were six assassins. Two carried grenades and four were armed with handguns newly manufactured in Belgium, designed by an American and selected by a Serbian colonel in the “Black Hand” terrorist underground. Like so many other revolutionaries of the left and right, the Balkan nationalists hoped to cut their way through history with a murder.

The first attacker threw a grenade. He missed his target, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who sat in the back seat of a slow-moving touring car with his wife, Sophie, the Duchess of Hohenberg. The grenade bounced onto the ground and detonated beneath a trailing automobile. Arriving at city hall, the unharmed archduke scolded the Sarajevo mayor, “I come here on a visit and I am greeted with bombs. It is outrageous!” and then drove off to comfort the now-hospitalized wounded. En route the archduke’s driver took a wrong turn, the car slowed to a stop, and there on the sidewalk was Princip.

There were 1.25 million Browning pistols circulating in Europe by 1914.

The gun that appeared in his hand represented the pinnacle of small arms manufacture. In design and function it demonstrated an unrivaled combination of mechanical invention and aesthetics. The curved and contoured steel, combined with the ornate initials “FN” on the grips, gave it visual cues that echoed the elegance of Europe’s “Belle Epoque,” the era Princip would soon end. In the hand—and the gun was meant to be fired with a single hand—the weapon balanced well, was easily gripped, and pointed naturally at a target.

A short movement of the index finger fired a round. The exploding propellant shot the bullet down the barrel. The effect was to make the gun jump in Princip’s hand as the recoil energy operated the semiautomatic firearm. The slide, a steel cover surrounding the barrel, flew backward, ejected the spent cartridge, cocked the mechanism, and loaded a fresh cartridge. Faster than could be seen, almost faster than could be conceived, the gun was ready to fire again. It was like a small combustion engine, only held in your hand.

The gun was no sharpshooter’s weapon. Made by Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre and named the FN 1910, it was meant for self-defense or close-in police work. It slipped smoothly from a pocket and was very accurate over a short distance. And as Princip proved when he fired two bullets, one striking the archduke’s neck, the other Sophie’s stomach, it could also be used to start a world war.

Its creator was the American John Moses Browning. Thanks to the scope, variety, and particularly the mechanical ingenuity of his inventions, there were 1.25 million Browning pistols circulating in Europe by 1914. His name was synonymous with pistols of all types. (The French referred to any pistol as “le browning.”) Across the Atlantic, however, Browning remained unknown to the general public, even though millions of Americans owned or used a firearm he’d invented and then sold or licensed to famous firms, including Winchester, Colt, Remington, and Savage. They were rifles, shotguns and pistols, and soon machine guns. As Henry Ford was to automobiles, and Thomas Edison was to electricity, Browning was to firearms, and his inventions had similar world-changing influence. Unlike those contemporaries, Browning sought no publicity. His relative obscurity lasted until 1917, late in his life, when the United States entered World War I and Browning found himself suddenly elevated to the status of a national icon.

He was a straight-backed man, over six feet tall, whose most visible luxury was the elegant brick and stone home with splendid oak woodwork he shared with his wife, Rachel, and their eight children. That Browning would live a life that curved history was inconceivable when he was born, before the Civil War, in the isolated frontier settlement of Ogden, Utah, where in 1865, at age ten, he began a career in guns.

*

Browning’s first firearm was a crude shotgun, fashioned from a discarded musket barrel as long as he was tall. He built it in his father’s workshop in less than a day and afterward went hunting in the grass of the high plains with Matt, his five-year-old brother and future business partner.

The 1865 Browning home in Ogden, Utah, was adobe brick, situated a few steps away from untrammeled land filled with grouse, a small wildfowl that made tolerable eating once it was plucked, butchered, and cooked, preferably with bacon fat to moisten the dry flesh. Utah’s five varieties of grouse could fly, but mostly the birds shuffled about on the earth. The male “greater” grouse reached seven pounds, making a decent meal and an easy target, as yellow feathers surrounded each eye and a burst of white marked the breast. A skilled hunter could sneak up on a covey picking at leaves and grasses and with one blast of birdshot get two or three for the frying pan.

Browning’s first firearm was a crude shotgun, fashioned from a discarded musket barrel as long as he was tall.

Such frugality was necessary. The closest railroad stop was nearly one thousand miles east, and the largest nearby town was Salt Lake City, 35 miles to the south and home to only ten thousand people. Ogden’s settlers ate what they grew, raised, or hunted. Water for drinking and crops depended on the streams and rivers that flowed west out of the mountains into the Great Salt Lake, and irrigated wheat, corn, turnips, cabbage, and potatoes. Each settler was obliged to contribute labor or money to construct the hand-dug ditches and canals. They made their own bricks, cured hides for leather, and made molasses out of a thin, yellowish juice squeezed from sugar beets with heavy iron rollers and then boiled down to a thick, dark bittersweet liquid.

The rollers were made by John’s father, Jonathan, himself a talented gunsmith who also doubled as a blacksmith. Jonathan’s shop was his son’s playground, and John’s toys were broken gun parts thrown into the corner. At age six, John was taught by his “pappy” to pick out metal bits for forging and hammering into new gun parts. Soon the boy was wielding tools under his father’s direction.

To build that first crude gun John chose a day when his father was away on an errand. From the pile of discards John retrieved the old musket barrel and dug out a few feet of wire and a length of scrap wood. He clamped the barrel into a vice and with a fine-toothed saw cut off the damaged muzzle. He set Matt to work with a file and orders to scrape a strip along the barrel’s top down to clean metal. With a hatchet John hacked out a crude stock. The boys worked intently. On the frontier a task didn’t have to be polished, but it had to be right. Basic materials were in short supply, and to make his gun parts and agricultural tools Pappy Browning scavenged iron and steel abandoned by exhausted and overloaded immigrants passing through on their way west. Once, he purchased a load of metal fittings collected from the burned-out remains of an army wagon train, and as payment he signed over a parcel of land that, years later, became the site of Ogden’s first hotel.

John used a length of wire to fasten the gun barrel to the stock, then bonded them with drops of molten solder. There was no trigger. Near the barrel’s flash hole John screwed on a tin cone. When it came time to fire, gunpowder and lead birdshot would be loaded down the muzzle and finely ground primer powder would be sprinkled into the cone. The brothers would work together as a team: John would aim, Matt would lean in and ignite the primer with the tip of a smoldering stick, and the cobbled-together shotgun would, presumably, fire.

This wasn’t without risk. There was no telling if the soldered wire was strong enough to contain the recoil, or if the barrel itself would burst. Then there was the matter of ammunition. Gunpowder and shot were expensive imports delivered by ox-drawn wagon train. And the Browning brothers’ makeshift weapon might prove ineffective, or John could miss, and anger their father by using up valuable gunpowder with no result. Despite the risks, John pilfered enough powder and lead shot (from Jonathan’s poorly hidden supply) for one shot.

In ten minutes the brothers were in open country. Ogden’s eastern side nestled against the sheer ramparts of the Wasatch Mountains, and to the west lay the waters of the Great Salt Lake. To the north the Bear and Weber rivers flowed out of the Wasatch to sustain the largest waterfowl breeding ground west of the Mississippi River. Early white explorers were staggered by seemingly endless flocks of geese and ducks. In the 1840s pioneers described the “astonishing spectacle of waterfowl multitudes” taking to the air with a sound like “distant thunder.” Mountains rose up in all four directions, with one range or another flashing reflected sunlight. It was a striking geographic combination, magnified by the bright, clear sunlight of Ogden’s near-mile-high elevation. A settler’s life was lived on a stage of uncommon spectacle.

John carried the shotgun while Matt toted a stick and a small metal can holding a few clumps of glowing coal. The idea was to take two or three birds with a single shot, thereby allaying parental anger with a show of skilled marksmanship. Barefoot, the brothers crept from place to place until they spotted a cluster of birds pecking at the ground. Two were almost touching wings and a third was inches away. John knelt and aimed. Matt pulled the glowing stick out of the embers, almost jabbed John in the ear, and then touched the stick to the tin cone to fire the shot. The recoil knocked John backward—but in front of him lay a dead bird. Two other wounded fowl flapped nearby. Matt scampered ahead and “stood, a bird in each hand, whooping and trying to wring both necks at once.”

The next morning, as Jonathan breakfasted on grouse breast and biscuits, John listened to sympathetic advice from his mother and chose that moment to tell Pappy the story of his gun, his hunt—and the pilfered powder. Jonathan sat quietly and when John was finished made no mention of the theft. He did ask to see the weapon and was unimpressed. “John Moses, you’re going on eleven; can’t you make a better gun than that?”

Matt snickered. John choked down his remaining breakfast. “Pappy has drawn first blood, no doubt about that. He hadn’t scolded about the powder and shot, and the sin of stealing. But he’d hit my pride right on the funny bone,” John told his family decades later. A moment later he followed his father into the shop. He unrolled the wire from the barrel, “whistling soft and low to show how unconcerned I was,” and then stamped on the stock, snapped it in two, and tossed the pieces into a pile of kindling. “I remember thinking, rebelliously, that for all Pappy might say, the gun had gotten three fine birds for breakfast. Then I set to work. Neither of us mentioned it again.”

The father, Jonathan, who was tutor and goad to his son John, was born in 1805 to a family that emigrated from Virginia to rich farmland outside Nashville, Tennessee. At 19 years of age apprenticed himself to a Nashville rifle maker, opened his own shop in 1826, and in November, married Elizabeth Stalcup. She was 23, the only child of a widowed mother. In 1834 they began a move to Illinois, the start of a decade-long trek westward as they added children at the rate of one infant per year.

The extended Browning family included a cousin, Orville, a politically ambitious attorney who practiced real estate law. Orville was elected to the state legislature, where he befriended another young lawyer, a tall, thin man with a distinctive jaw named Abraham Lincoln. The men were of similar age and background. Both grew up in Kentucky, served in the state militia, and had similar politics—they were opposed to the expansion of slavery—which eventually led them to join the new Republican Party.

The two legislators became friends, and Browning family oral history says that at Orville’s behest Jonathan and Elizabeth, who enjoyed a relatively spacious home on account of their ever-expanding family, played host to Orville’s friends or clients in need of lodging. On two occasions young lawyer Lincoln was the guest. So the story goes, anyway. Research by a Browning descendant comparing the dates and locations in family lore with the available records of Lincoln’s travels wasn’t definitive but suggests the family lore is “likely” grounded in fact. One story does have a strong whiff of verisimilitude. At an evening meal with Lincoln, probably around 1840, Jonathan remarked how earlier that day he’d set a neighbor’s broken arm, a skill learned after trading a gun for a “doctor book.”

“Fact is, that’s the way I got my first Bible, traded a gun for it.”

Lincoln said that reminded him of “the saying about turning swords into plowshares—or was it pruning hooks?”

“Plowshares,” Jonathan replied.

“Well, that’s what you did, in a way turned a gun into a Bible. But the other fellow—he canceled you out by turning a Bible into a gun. Looks like the trade left the world about where it was.”

The men chuckled; then Jonathan admitted “there was something else funny” about the transaction. “To tell the truth, the mainspring in that old gun was pretty weak, and some other things . . .”

“You mean to admit that you cheated in a trade for a Bible—a Bible!” Lincoln exclaimed.

Jonathan said that the artful deal making went both ways. “When I got to looking through the Bible at home, I found that about half the New Testament was missing.”

Mending, be it bones or guns, was the evening’s favored metaphor. “The United States are to become the greatest country on earth. But what if the hotheads break it in two, right down the middle? That would be a welding job!” Lincoln declared. “It would need the fires of the infernal for the forge. And where was the anvil? Where is the hammer? Where was the blacksmith?” That blacksmith turned out to be Lincoln, and the fires four years of bloody civil war.

Of greater significance for the Browning family was Jonathan and Elizabeth’s introduction to another man, the charismatic Joseph Smith, who in 1823 declared that he’d found a new holy gospel written on golden tablets discovered buried in a New York hillside, and so was inspired to found a new religion, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or the Mormons. Forced to flee Missouri in 1839, Smith and his followers trekked to Illinois, where the new faith expanded. Unlike most other sects born during the spiritual revival of the mid-1800s, Smith’s religion provided a cohesive community and economic security, a “theocratic-democracy” that offered structure “for lives beset by unpredictability, disorder and change” amid the uncertainties, isolation, and insecurity of the frontier.

In 1840 a proselytizing Mormon in need of a gun repair introduced Jonathan to the faith and later presented Jonathan with the Book of Mormon. Jonathan wasn’t economically insecure—his business dealings were thriving. Though uneducated in any traditional sense, he was an ambitious, curious man who may have seen the church as an alternative to the many warring Protestant sects. It offered the promise of salvation and a comprehensive social network that was rooted in a patriarchal family structure. “He seemed to perceive a clearly marked road to salvation, a map in effect, to guide man through the wilderness of life to the gates of heaven,” his grandson Jack wrote a century later.

Jonathan was baptized into the church, and briefly became owner of a two-story home and gun shop. Around this time that Jonathan designed a second firearm, soon much sought after by his Mormon brethren. It was an ingenious device called the slide bar repeating rifle, colloquially named a harmonica rifle, since a vital part indeed bore a resemblance to the musical instrument.

In Jonathan’s harmonica gun five chambers were drilled in a steel rectangle, and each loaded with powder and ball. The loaded bar slid sideways into the rifle and was locked in place by a lever. With a pull of the trigger the hammer snapped forward, struck a percussion cap, and ignited the powder. To reload, the lever was released, the bar was slid over, and the next chamber was aligned with the barrel. About four hundred of the rifles were built over the next decade as the family traveled west, pausing in Iowa before setting out for Utah with eleven children and seven wagons of supplies and equipment, and carrying a respectable $600 in savings. They arrived in Salt Lake Valley on October 2, 1852, midway through the great Mormon migration.

By then Jonathan was 47 years old and had lived more than half his life. Nevertheless, he marked his arrival in Utah by starting two new families, permitted by the Mormon doctrine of plural marriage. In 1854 he married his second wife, a 37-year-old native Virginian, Elizabeth C. Clark. What the first Elizabeth thought is unclear, though some family accounts say displeasure prompted her to find separate living quarters.

The second Elizabeth and Jonathan had three more children. The first was John Moses, who arrived in 1855, followed by a sister who died as an infant in 1857. Two years later Elizabeth gave birth to Matthew. John Moses became the inventor and Matthew the financial wizard behind what eventually became a joint enterprise called the Browning Bros. Jonathan wed for a third time in 1858, marrying Ann Emmett, 28, an emigrant from the United Kingdom with a two-year-old daughter, Sarah, who died before she reached adulthood.

The families lived a simple, difficult frontier existence, in three different homes. One of Ann’s sons, T. Samuel, recalled their adobe home had only two rooms, two windows, and a dirt floor. “Mother made all of our clothes,” he said. “She would wash and card the wool, spin and weave it, and cut it and sew it.” The ubiquitous sagebrush was used as fuel for heating and cooking, and Jonathan “usually killed a beef, put it into brine and then hung it high above the fireplace to dry. We could just slice it off and I remember how good it tasted.” Unruly children were disciplined with “a strap on the seat of our pants.”

Jonathan branched out into new business endeavors, including a brickyard, a leather tannery, and a sawmill, though none brought prosperity. Grandson Jack described Jonathan with this carefully written paragraph:

Thus, versatile in imagination and mechanical skills, generous, never thrifty, obeying more wholeheartedly than most the admonition to “love thy neighbor as thyself” and, let it be admitted, gullible, Jonathan soon saw his shop turned into a kind of community first-aid station. He made a good deal of money, but always, as it came in a new project was waiting for it—or the outstretched hand of a borrower. If he had possessed a moderate talent for business management, he could have become wealthy. As it was, no man in the community worked harder, accomplished more, and had less to show for it. He lived in confusion, and seems to have been only mildly troubled by it.

The business failings of the father were not to be repeated by John and Matt.

Ogden’s isolated character abruptly changed in 1869 with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, 1,933 miles long and connecting Omaha, Nebraska, to a wharf on San Francisco Bay, with a major hub in Ogden. Chinese and Irish emigrants had built the line by hand, 40-foot rail by 40-foot rail, installing each with a choreographed display of hard labor. Divided into crews of a dozen men, the first laid down wooden crossties, atop which another crew laid one-thousand-pound iron rails. Lever men moved each rail into place, bolters connected it to the previous rail, and spikers pounded in ten spikes per rail. Then it was all repeated again, and again, and again. The Union Pacific crew working westward arrived in Ogden on March 8, 1869, to find the entire town gathered for a celebration. At 2:30 pm the coal-fired locomotive Black Hawk steamed into view, slowly rolling in on the newly laid tracks.

“A number of us boys had heard that it was coming,” Samuel said. “So we went out to the south end of town and climbed over a bank and heard it whistle.” He was nine years old and had never seen a train or heard an earsplitting steam whistle and found, “It frightened us very much.” The track crews worked into the center of town, and “when the train came into Ogden, and whistled, people were so frightened they ran in all directions.” Children fell into a muddy trench in their panic.

After the Black Hawk ground to a halt, a band played, artillery fired a salute, and a celebration lasted into the night. Track work resumed the next day, and on May 10, after another 57 miles of rail were laid, a Union Pacific train met a Central Pacific train at Promontory, Utah. The moment was recorded in the famous photograph of two locomotives head-to-head on a single track, surrounded by workingmen and dignitaries posing motionless for the camera.

The railroad changed the national concept of time. A trip from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, which previously took months, cost $1,000, and required either a voyage around Cape Horn or a trek across the disease-ridden Isthmus of Panama, was reduced to seven days, including stops. Within a year, $65 purchased a seat in “immigrant” class—on a bench—and a trip from one coast to the other. Equally important, freight no longer moved at the pace of an ox or horse, and the telegraph, paralleling the rails, joined cities and towns in near-instant communication.

The quality of life in Ogden also changed. Some Mormons worried that an influx of railroaders and non-Mormons would undermine the Latter-day Saints’ strict prohibitions against drinking, swearing, premarital sex, and gambling, and there was, inevitably, an influx of “Gentiles” and their less-than-Mormon practices. The wickedness reached its apogee at a transient “hell on wheels” labor camp in Promontory. Workers lived in box-cars surrounded by tents serving as hotels, restaurants, saloons, gambling dens, and brothels. There were con men, assorted criminals, and one fellow called Behind the Rock Johnny, said to have bushwhacked five people. Ogden’s population grew to ten thousand and it acquired the nickname Junction City, along with a red-light district of national repute.

The year of the railroad’s arrival also marked the end of John’s formal education. At age 15, he had completed the equivalent of eighth grade. His few teachers had only modest educations themselves, and one is said to have told John he’d exhausted his instructors’ store of knowledge. Life outside the classroom continued to offer an education of its own.

For nearly a decade, starting in the 1860s and ending in the early 1870s, a Native American—his tribe is unknown—appeared at the Browning homestead twice a year. He dropped a ragged bundle of possessions in the barn, set himself down at the base of an apple tree, and began constructing moccasins. “He never spoke, never even nodded; the lot might still have belonged to his people so did he make himself at home,” Jack wrote. Once or twice a day Elizabeth sent John out with a meal. In the first years the young Browning delivered the food and wandered away, until one day he delivered an extra ration of food and asked the Indian to show him how to cut and sew the deerskin into footwear. “Although there was no exchange of words, there was doubtless a spiritual confabulation between the two creative artists. John was permitted to pick up this or that piece for close examination, to slip a hand into a finished moccasin, and trace every seam,” Jack wrote. Years later Browning came across a display of Native American handiwork and showed his children the little tricks of construction taught to him as a child.

He also built himself a bow and carved and fletched his own arrows, becoming sufficiently skilled to trade his handiwork to siblings and neighbors’ children in return for their labor. “He could get his chores done for a week for a bow and a couple of arrows.” Of course, the buyer would soon need additional arrows, which John traded for eggs, potatoes, and the occasional nickel.

By 1869 Browning possessed a range of metalworking skills. He could saw, file, weld—hammering strips of metal into a larger, stronger piece—and use a hearth and bellows to forge and shape iron and steel. That spring a freight wagon driver arrived with a finely made but now badly damaged single barrel shotgun. It had been crushed when a wooden cargo box fell on the stock and metal parts—the trigger, springs, hammer, and levers that comprise a firearm’s “action.” The barrel was intact, but the warped and twisted action made the cost of repair exorbitant. The customer was both in a hurry and drunk, the story went, so he purchased one of Jonathan’s reconditioned guns with a $10 gold piece. On his way out he handed the seemingly useless shotgun to a surprised and pleased young John.

Unconstrained by time or the need to turn a profit, Browning saw an opportunity, as the expensive barrel was the one part Jonathan’s shop couldn’t replicate. He laid the damaged gun parts out on the bench for a close inspection and felt his confidence vanish. John had no idea what, exactly, to do. Where to begin? How was he to convert this mashed-up collection of metal and wood into a functioning firearm? Frustrated, stewing in a potent mix of youthful anger and pride, with the chance to own the best shotgun in town disappearing before his eyes, John burst out with a curse. “Damn it to hell!”

On the other side of the shop Jonathan was shaping metal parts for a sawmill, his latest entrepreneurial effort. He looked up and pointed a big steel file at his son. “John Moses, don’t you know that everything you say and do is recorded?” And jabbed the tool skyward.

For young John it was a moment of sublime exasperation, followed by the discovery that the unconscious mind, stimulated by stress, can solve the previously insoluble. Spurred by his irritation, Browning’s mind spit out an idea, and he hit on the thought process that underlay his work for the next six decades.

“A good idea starts a celebration of the mind, and every nerve in the body seems to crowd up to see the fireworks,” he said years later. “It was a good idea, one of the best I ever had, and so simple it made me ashamed of myself.”

“Boy-like—and very often man-like too—I had been trying to do the job all at once, with some kind of magic,” Jack wrote in the 1950s, quoting the story told by his father decades earlier. Browning at that young age taught himself how to solve mechanical problems by first discovering where to start—importantly the correct place to start—and then proceeding in a strict sequence. “The oldest ‘step at a time method,’” he called it. “The idea was no great shakes itself,” but as he correctly observed, “It requires a lot of patience and a good many men get discouraged and quit.”

The years already spent in his father’s shop also proved their value. “It seemed as though every haphazard bit of knowledge I picked up playing in the shop, watching Pappy, doing little jobs for him, and every knack I’d learned they all bunched together and focused like a lot of little lights. In the aggregate to make quite an illumination. I learned right there how to use your brain.”

The next morning he spread the parts across the workbench and, as he examined each piece, saw “that there wasn’t one I couldn’t make if I had to.”

John rebuilt the shotgun in two months, finding time between chores and work in the shop. The quality of his final product was on par with the high-end barrel, though Jonathan couldn’t quite come out and say so. Instead, he offered a thick plank of expensive walnut for the shotgun’s new stock.

As he grew out of his teens Browning realized a life spent repairing old muzzle-loaders offered only terrible boredom. It would have taken an exceedingly dim mind not to be inflamed with curiosity and restlessness by the strangers crowding Ogden streets, borne back and forth across the continent by locomotives moving east and west at all hours of the day and night. Browning could have pursued other work—the railroad would have welcomed a talented mechanic—but he never did so: “I couldn’t bring myself to ask anybody for a job. It seemed to me that by the act of asking a man for a job I admitted my inferiority to him.” Browning added, “The fact is, I was lazy.” If so, it was laziness only by Browning’s definition: “The only shop work I liked was gun work.”

Indeed. By the time of Browning’s death in 1926 he had invented rifles, shotguns, pistols, automatic rifles and machine guns that long survived him. If his first small pistol started World War I, then it was his other guns what won World War II—his .45 caliber 1911 pistol, his Browning Automatic Rifle and his .30 caliber light machine gun carried by millions of soldiers, and his .50 caliber heavy machine gun that armed all 300,000 American fighters and bombers. Every American battle on land and air was fought, and mostly won, with Browning’s guns.

__________________________________

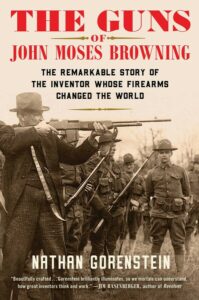

Excerpted from The Guns of John Moses Browning by Nathan Gorenstein. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Nathan Gorenstein.

Nathan Gorenstein

Nathan Gorenstein is a former reporter and editor for The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he covered city and state politics and produced a wealth of groundbreaking work. He was previously a reporter for the Wilmington News Journal, where he led coverage of Sen. Joseph Biden’s first presidential campaign. He is also the author of Tommy Gun Winter, the story of a Boston gang from the 1930s that included an MIT graduate, a minister’s daughter, and two of Gorenstein’s own relatives. He currently lives in Philadelphia.