Uncle Vanya and George Clooney: Julianna Margulies Recalls the Tipping Point of Her TV Career

“In that moment I felt like I was playing Russian roulette.”

After the ER pilot filmed, I said goodbye to the cast, wishing them luck with the show, packed my bags, and flew back to New York. After one week home, I was offered a job as a series regular for a show I had guest-starred on the year before called Homicide: Life on the Street, which filmed in Baltimore. Tom Fontana, the showrunner, to whom I owe my career in many ways, called to say that they wanted me to join the cast.

He and I had met when he cast me in a pilot the year before in a small recurring role. That show was about firefighters, and the part was for a character named Linda, a nurse at a Philadelphia hospital and the almost ex-wife of the main character. Tom was the first person who fought for me. The network felt that I was too ethnic looking for the part; they wanted an all-American girl. Tom was set on casting me and took them to task, eventually winning that fight. I heard that a lot during my auditioning years: What is she? Black? Hispanic? Black Irish? I never heard Jewish, but the feedback was, more often than not, that I looked un-American.

My first day of the shoot was fairly simple. I had one tiny scene, where I run to peer through the window in the door to a hospital room where my husband is lying in bed. He’s been in a ravaging fire that injured him badly and killed his captain, a man he looked up to as a father. He is weeping, inconsolable, and alone. That was all I had to do, just look.

I was waiting in my trailer, the size of a postage stamp (the bench I sat on doubled as the toilet when you lifted up the seat), but I didn’t care, I was just so happy to be there. Being paid to sit and wait was a new experience for me, one that I found quite luxurious.

The wait for my scene became longer and longer; production assistants popped their heads in from time to time to apologize and ask me if I needed anything. After about six hours, Tom and the director came to my door, apologizing profusely for the long wait, and told me they were having a difficult time filming the scene. The actor playing my husband couldn’t get there emotionally and they really needed that emotion to hook the audience, to make them care for the main character. Tom announced that he’d rewritten the scene and was wondering if I could do him a favor.

“I would love it if you could run to the door, look at him lying there, and break down crying. I think that will show the audience how well you know him, that even though your marriage is on the rocks, you know he is weeping inside after what happened. You cry for him, for the pain he’s in that he can’t express. That way the audience will understand just how devastating losing his captain is to him.”

“So . . . you want me to look in, cry, and walk away?” I asked, trying to picture the scenario in my head.

“Yes! I know it’s not in the script, but we need to be creative here, we’re losing this location in an hour and we need the emotional aspect of this scene. Otherwise it just won’t work.”

My brain started ticking, trying to figure out how to get there emotionally in such a short time with no dialogue.

“Okay . . . Do you think I could have five minutes somewhere quiet on set to figure this out before you film?”

“Whatever you need,” Tom said with a small smile spreading across his face.

While they set up the shot, I was ushered into a fire exit stairwell next to the room they were shooting in. I began to recite the only thing I could think of to bring me to tears, the last monologue in the play Uncle Vanya, where Sonya tells her uncle that one day they shall rest:

What can we do? We must live our lives. Yes, we shall live, Uncle Vanya. We shall live through the long procession of days before us, and through the long evenings; we shall patiently bear the trials that fate imposes on us; we shall work for others without rest, both now and when we are old; and when our last hour comes we shall meet it humbly, and there, beyond the grave, we shall say that we have suffered and wept, that our life was bitter, and God will have pity on us. Ah, then dear, dear Uncle, we shall see that bright and beautiful life; we shall rejoice and look back upon our sorrow here; a tender smile, and we shall rest. I have faith, Uncle, fervent, passionate faith. We shall rest. We shall rest. We shall hear the angels. We shall see heaven shining like a jewel. We shall see all evil and all our pain sink away in the great compassion that shall enfold the world. Our life will be as peaceful and tender and sweet as a caress. I have faith; I have faith. My poor, poor Uncle Vanya, you are crying! You have never known what happiness was, but wait, Uncle Vanya, wait! We shall rest. We shall rest. We shall rest.

That monologue brings me to tears every time I read it. The words are enough to carry you, they transport you on their own. There’s no need to act; just say the words, that’s all you need.

Someone popped their head in to say they were ready for me. The director yelled, “Action!” I ran up to the window, looked inside the room, and silently wept for Sonya and Uncle Vanya. One take. Done. Wrap. Go home.

Tom never forgot that. The pilot didn’t get picked up. But Tom remembered me and cast me as a guest star on Homicide, which I filmed a few weeks before I headed out to LA to visit my boyfriend. (On a funny side note, years later ABC aired the pilot episode and critics chastised Tom for being so unoriginal by casting me as the nurse. Just for the record, Tom Fontana was the first person to cast me as a nurse.)

*

So there I was, back in my walk-up apartment on Fifty-third Street and Second Avenue, having just returned from shooting the ER pilot. I could never hear myself think in that apartment, with all the traffic barreling down Second Avenue. How quickly I had forgotten about this noise when I was in my Laurel Canyon hideaway.

The restaurant that occupied the corner storefront of my building was called the Royal Canadian Pancake House. Their gimmick was that their pancakes were the largest ever served and what you couldn’t eat went to the homeless. On Sunday mornings there were lines all the way down Fifty-third Street to First Avenue. If only those people knew about the little rodents that squeaked through my kitchen radiators, fat and content from these doughy, large discs of sweetness. I bought Brillo pads, cut them up, and stuffed them into any hole I could find, hoping to redirect the mice’s journey away from my kitchen.

In that moment I felt like I was playing Russian roulette. How could I walk away from Homicide, a firm gig, without a direct offer from ER.I was standing in my apartment, excited about the Homicide offer and nervous at the same time. I would have to move to Baltimore if I took this job, but Tom Fontana and Barry Levinson were at the helm of this heralded show filled with great actors, and it would be a full-time job! I wouldn’t have to worry about money for a long time; maybe I could even move to a quiet, mouse-free apartment. I decided to go for a run in the park to clear my head before calling Tom back. Moving to Baltimore was a huge decision for me. I needed a minute to adjust to the idea of it. But to tell the truth, I knew I would take it; this was a great opportunity and I was in no position to turn down work.

When I got back to my apartment, there was a message on my answering machine. It was George Clooney:

Hey, it’s George, I heard through the grapevine that your character tested really well. I can’t say for sure, but if you are thinking about taking another job you might want to hold off. I think they are going to offer you something on ER.

I was shocked. How on earth could they offer me anything? My character overdosed in the pilot, I came in brain dead on a gurney.

I called George and asked him specifically what he knew. He said he had been to a screening and overheard Steven Spielberg tell John Wells that they should keep me on, the character was too interesting to lose. Plus he knew from John Levey that when they tested the pilot, audience members were unhappy that my character died.

In that moment I felt like I was playing Russian roulette. How could I walk away from Homicide, a firm gig, without a direct offer from ER. And even if I did walk away and I got the job on ER, a first-time TV show was a crapshoot; you never knew if it would actually make it to a second season. Homicide was a seasoned show, already going strong. Who was I to walk away from that? I needed job security.

I called Tom to tell him of my dilemma. In two minutes he set me straight.

“I think you should wait and see if they offer you ER.”

“Really? But what if they don’t? Then I’ve walked away from Homicide and I’m back to being unemployed.”

There was a gentle silence on the other end of the phone, and then Tom said, “Sometimes in life you have to take the risk of losing something in order to gain something. But I can promise you if the ER gig doesn’t work out, I’ll find you a role on Homicide.”

A few days later I was offered the role of Nurse Hathaway on ER. That decision changed my life. Till the day I die I will be thankful to Tom and George.

___________________________________________________

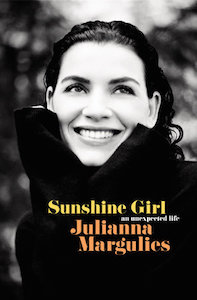

From the book Sunshine Girl: An Unexpected Life. Copyright © 2021 by Julianna Margulies. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.