The Grief of Displacement: On Being a Child in a Refugee Camp

Mondiant Dogon Considers the Experience of Collective Suffering

In April 1996, the land surrounding the Congo‑Rwanda border was a whirlpool of lost and forgotten people. Refugees and internally displaced people had walked or been driven to the camps established on both sides, where families eaten through by genocide and war tried to put themselves back together. People around the world thought that the Rwandan genocide was over, but for millions of people living in Rwanda and the surrounding countries, our suffering was just beginning. North Kivu was on the brink of a new kind of war that would last for decades. Hundreds of thousands of newly displaced wandered, looking for places to rest. We lived on top of graveyards.

My own broken and distraught family first arrived in a refugee camp just across the border in Rwanda, only about two miles from Goma, the capital of North Kivu. Almost one year had passed since we left Bikenke and I was still very young, and at first I saw the camp like a child would. I was excited to see that the tents were big enough to share with other families, and I hoped those families would include young kids like me. I barely noticed the UNHCR logo, a laurel and a pair of hands encircling the figure of a person, all in bright blue, stamped on the sides of the tents, salvaged from previous camps. I had no idea how that logo would follow me and my family for decades, becoming at once a sign of hope, a symbol of all we had lost, and a branding of who we had become.

When I was a young boy, I thought those tents were beautiful; after so much time sleeping in the forest, hiding from murderers, I wasn’t used to having anything over my head. Sunlight filtered through the plastic and cast my gangly shadow far across the dirt floor. It was like living inside the sun. I played with the shadows of other kids, still strangers, darting back and forth through the tent, chasing the patterns, laughing. The camp grew with hundreds of new, glowing tents. I was a child. I thought, Wow. I felt sorry for my older siblings, who had to act mature. They stood with my parents in line to register with the Red Cross. “Where are you living?” The workers asked impossible questions. “Where did you come from?” The same time we learned the word “refugee,” we learned about the massive organizations that would at times seem designed to help us, at others to hold us back. Our first day in a refugee camp, we took comfort in the presence of the Red Cross. We thought of them as our rescuers.

Maybe I would make friends. Were there only Tutsis in the camp? Were there Hutus as well? Hunde? I didn’t know. They gave us cookies! Crumbly cookies the color of fresh milk, which they shook out of large cellophane packets directly into our hands. At home cookies were a rare treat, brought to Bikenke by a visitor or bought by my mother, and handed out after dinner like she was a priest blessing our childhood.

It was as though we had left our individual identities in our towns and villages when we fled.

We arrived to find tents pitched on hard, black rock. “It’s from when Nyiragongo erupted,” another kid, a bit older than me, said, pointing to the massive volcano that loomed in the near distance. Mount Nyiragongo, with its massive, active lava lake, was more powerful than anyone living in its path, whether refugees or Interahamwe. The hard ground beneath our camp had been scorched by previous eruptions. Even Congolese living busy city lives miles away in Goma feared that one day their homes would be buried. It had erupted 14 years before we arrived in the camp, and the ground was still scorched.

At first, there weren’t enough tents. We spread mats, also UNHCR branded, on the rock, lying down and staring up at the night sky until sleep came. We were starving, but not sure who was there to help us. Some people had been so ravaged by ants they had to walk delicately on the sides of their feet, wincing and on the brink of tipping over.

I was a child; I watched everything like it was a movie. Fear felt like a cut my mother could heal, her comforting words a bandage. One second I was scared, and the next I was fine, curious, close to happy.

My aunt Agnes, my mother’s youngest sister, though, couldn’t stop crying. “I don’t like sleeping outside,” she told me.

Agnes was 23 when we fled Bikenke, and recently married. She was very tall and striking. When her new husband was nearby, Agnes looked even more beautiful. “We’re going to have a lot of children,” she said to my mother, giggling. On the day of the attack, her husband was watching the cows. He never showed up at the cave or the school, although Agnes watched every day for him. After a while, everyone assumed he was dead, but my aunt kept waiting. “It’s just the wind, Mondiant, that makes my eyes water,” she told me one day. “I’m just crying because of the ants,” she insisted, on another day.

In the camp, we began to experience the empty time that comes with being displaced from your home. After months of running and fearing for our lives, we had time to think. We thought about home and the people we had left. We thought about how close we had come to dying. We thought about the volcano that was now always in sight, boiling its lava and waiting for the day it would turn us into rocks.

While we played, we were oblivious, but the refugee camp was a dangerous place for children. We would drown while fetching water from Lake Kivu. We would fall into ditches that were dug for latrines, the walls of mud caving in on us. We would get lost, running over black rock between endless rows of identical tents until it all became one big indistinguishable mass. Even the adults we passed began to look the same, their appearances muted by identical expressions of grief and fear. They had lost weight and were tired. They wore torn and dirty versions of the clothes we recognized. They couldn’t protect us as we’d thought they could, and so none of them were really our parents; maybe they weren’t even adults. Seeing us running through the camp and knowing how easy it was for children to injure themselves, Red Cross workers would catch us and try to reunite us with our families. “What is your name?” they asked, and we would tell them, wondering if we were in trouble. But when they asked us the names of our parents, many of us shook our heads. “Mama and Papa,” we would say, and wonder if we would be lost forever. Parents cried every day looking for their lost children.

Our thoughts became weapons we used against ourselves. People sank into grief, retreating from the world. Others were angry, picking fights. Some mothers, unable to care for their children, killed themselves in the nearby lake. “I’m going to the market,” they would say, and then walk down to the water. After a few days the government started building a fence around the camp.

I often remember those years as only a collective experience. We fled, we thought, we remembered. We collected our tents and our cookies. We listened to stories about the changing world around us—the war, the genocide, the new leader in Rwanda, the volcano that we swore we heard rumble above us, the other borders we might have to cross. Who was protecting us from the killers now? How long would it take to get home, and when would we be able to go? It was as though we had left our individual identities in our towns and villages when we fled. We hoped, we prayed. We laid out UNHCR mats side by side in our UNHCR tents and we tried to stop thinking about what we had all been through, and then one by one the luckiest among us fell asleep.

For me, the camp quickly became unremarkable. When you’re that young, suffering becomes routine. Everyone slept outside, so sleeping in the dust was no big deal. Everyone got sick, so I wasn’t scared of getting sick. After almost a year in the forest, I thought, Wow, the world is so dangerous. I was relieved to be in the camp. I didn’t think about serious things anymore. Compared with life in the forest, I was in heaven. But we didn’t stay long.

One day a man—a father not much older than my own—was shot while he put up his tent. The bullet seemed to come from so far away that I thought, watching him fall, that he had tripped over something or been pushed over by an invisible force, maybe the wind, maybe the angry spirit of the volcano watching over us. “Did he have a heart attack?” people wondered, forming a circle around him. My father knew. “Faustin, get your mother’s kitenge,” he said, and they ran to the man’s side, where a pool of blood had begun to form.

“He’s dead,” my father announced, spreading the kitenge over the body. “He’s been shot.” Hutu rebels were targeting us from a nearby camp. “These are the people who did the genocide,” people whispered. I didn’t understand why the government would make a camp for Hutus. I thought, again, who did they need protection from?

We began to forget that any of our Hutu neighbors in Bikenke had ever been our friends. A gulf opened between us, so that no amount of evidence of their own suffering could bring us back together. My mother and father and the church had taught me to love everyone. When we’d prayed in Bikenke, it was outside, Hutus and Tutsis together under the open Kivu sky until it rained and we found shelter. I was too young then, and I didn’t really understand the difference between a Hutu and a Tutsi. My mother and father had loved their Hutu friends, and had we stayed in Bikenke, their sons and daughters would have grown up to be my friends. But in the tents in that first refugee camp, I started to hate them.

__________________________________

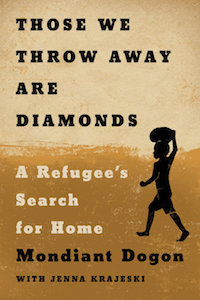

Excerpted from Those We Throw Away Are Diamonds: A Refugee’s Search for Home. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mondiant Dogon.

Mondiant Dogon with Jenna Krajeski

Mondiant Nshimiyimana Dogon is an author, human rights activist, and refugee ambassador. Born into a Congolese Tutsi family in Bagogwe tribe in North Kivu province, at age three he was forced to leave his home village, Bikenke, because of the Rwandan genocide against Tutsis that spilled over into the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Jenna Krajeski is a reporter for The Fuller Project whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Nation, among other publications. She is the coauthor of Nobel laureate Nadia Murad’s memoir, The Last Girl, and was a Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan.