The Dark, Orwellian Power of Steve Bannon, on Display at CPAC

Timothy Denevi Gets a Little Too Close to the Real Power in the White House

It’s just after 10am at the Potomac Ballroom of the National Harbor Convention Center and Donald Trump is walking slowly toward the microphone. With each step he appears to stoop forward, his midsection slung out like a weight beneath the long arcing sweep of his spine. He reaches the podium. He grabs it on both sides. He slaps it. He grins in that flat, familiar manner. And when he finally straightens up, his head seems to take on a spectral glow—the lights are shining down on him from multiple angles, a blanching wash—and for an instant his hair assumes something of a gossamer density: threaded and translucent and finely spun.

He nods. He’s speaking deliberately. “I love you people,” he says.

I’m standing perhaps thirty feet away, along a stretch of wall that a secret-service agent has permitted me to lean against, despite the ballroom’s overflowing crowd. It’s Friday, February 24th: day three of the Conservative Political Action Conference, the annual gathering of Republican activists from all across the country.

“Dishonest media,” Trump muses now. He’s warming up, you can feel it. “They’ll say: ‘He didn’t get a standing ovation…They’re the worst!” And it’s at this precise instant—amid the cheers and shouts and chants of “USA! USA!”—that Donald Trump transforms.

He claps loudly. He circles behind the podium. He sidles back and forth. He’s light on his feet. Once again he has an enemy in his sights—“the dishonest media”—a necessary engine to the performance he’s about to give.

Make no mistake: it’s not as if the heavy-set 70-year-old up on stage suddenly seems younger or healthier—he still can’t escape his physique: that of a large elderly man who’s long since lost the ability to hide his profile with expensive suits—but what’s clearly changed is the style of the act he’s putting on. Everyone can see it. On stage, he’s become equal parts Mamma Cass and Don Rickles: a fleet and menacing sock-puppet brought glaringly to life, as big and unpredictable as a drunk college fullback willing to yell out whatever pops into his head next.

But all Trump can seem to think of, for the moment at least, is the national press. He calls them “enemies” of the American people and the crowd loves it; a few rows to my left someone even shouts, “They’re liars!” Trump hears this, nods. With his right hand he karate-chops the air. “They leave out the part: They never sat down!”

And for the next forty minutes, his words will unfurl quickly and boisterously. Some of the things he’ll say (as recorded in my notebook):

“False narrative!” “Fake news!” “No more sources!” “How many elections do you have to have?” “We get the drugs, they get the money!” “Beautiful clean coal!” “I will never apologize.” “I love setting records.” “I like Campbell’s Soup.” “Historic movement!” “The likes of which!” “I won’t say it was because of me—but it was!” “Nobody’s going to mess with us.” “Greatest military buildups.” “Totally obliterate.” “Take a look! Take a look! Take a look!” “Blood sucker consultants.” “Sucking the blood.” “The color of the blood we bleed.” “Bigger and better and stronger!” “Jim!” “Paris!” “City of Lights!” “It’s going to be…It’s going to be…” “America!” “Remember…” “Roaring!”

When all is said and done, the speech itself (if that’s the right word) will feel more like a free-association therapy session, and as I stand there against the wall of the Potomac Ballroom trying to follow along—standing within spitting distance of a man we usually only experience through the foreshortened lens of broadcasted video—I find myself arriving at a perspective I’ve failed, until now, to consider: for Donald John Trump, expression is a physical act.

As in: it’s not just that he’s made a career of saying whatever the fuck jumps into his head—no matter how offensive, threatening, or batshit it might sound—but that the elemental substance of this expression resides in the stunning grotesquerie of girth and freneticism that really only makes sense when viewed close-up, in a normal-sized room, during a live performance like the one I’m witnessing now.

After all, we’re talking about a man who clocks in somewhere around 250 pounds and well over six feet—who’s personally admitted, on tape, to sexually assaulting women in a manner that depends in part on the advantages such size provides—and to watch his enemy-hating frenzy of a speech from only a few dozen feet away is to acknowledge, on a certain level, that the form of his commentary has always been inseparable from its function.

I’ve seen Donald Trump speak on two previous occasions—last summer at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, and again, recently, at his Inauguration—but both times I was thousands of feet removed; really, I might as well have been streaming him on my phone. Or to paraphrase the late David Foster Wallace: Donald Trump on TV is to live Donald Trump pretty much as video violence is to the felt reality of human suffering.

On this morning, as he shouts and sways behind the Potomac Ballroom’s bright podium, I’m beginning to wonder if the speech I’m hearing will ever come to an end. At one point—this is about halfway through—I find myself noticing, as if in a dream, that the people around me all seem to be glancing in my direction.

Did I say something? I wonder. Are they on to me? For the conference I initially applied for a media pass, but my request was denied—and fair enough: the anti-Trump content of my Twitter account pretty much reads like a hastily compiled FBI file—and to be completely honest, I have been planning to shout something: a short phrase that, in a space like this, Trump and everyone else will be able to hear.

In other words: as our enormous, frenzied, and deeply agitated president extemporizes viciously on the many threats he alone will protect America against, I’m hit by a genuine flash of paranoia.

But in the next moment it passes; I realize that the true object of attention is located perhaps ten feet to my right.

A man has just emerged from behind the blue security curtain. I recognize him immediately; we all do. The day before I heard him speak at the same podium Trump occupies now. He’s dressed in a long black coat that seems way too heavy for our DC winter—let alone a ballroom. His shirt is open at the collar. The skin beneath his chin is loose and pale, an unshaven wattle. His gray hair is slicked back. He looks, in a word, unhealthy.

The person I’m talking about is Steve Bannon: former Navy officer and Goldman Sachs banker who, after making a fortune investing in Seinfeld rights, went on to help create the white-nationalist magnet Breitbart News—an outlet he resigned from, last summer, to serve as the executive officer on Donald Trump’s campaign.

Now, in his current role of Senior Counselor to the President, he resides on the Principals Committee of the National Security Council. In short: he is, along with Trump, one of the most powerful people on the face of the earth…

He’s also, as it turns out, a self-proclaimed advocate of globalized chaos. “Lenin wanted to destroy the state,” he reportedly told a correspondent from the Daily Beast in 2013, “and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down.”

*

Two days earlier, I arrived at CPAC not knowing what to expect. The conference, held annually for more than four decades, got its start by catering to the Republican Party’s more traditional wing: a place for mainstream politicians and activists to exchange ideas.

This no longer appears to be the case. What’s more, the controversy surrounding the 2017 gathering has been especially intense. Earlier this week, one of its keynote speakers, bigoted attention-seeker Milo Yiannopoulos, was very publicly uninvited—for his comments about pedophilia, specifically, as opposed to the vast effluence of hate he’s spent a career spewing out—and only a few days later, on Thursday, conference organizers found themselves in the awkward position of having to eject from the premises the Nazi-saluting white supremacist Richard Spencer.

Not that any of this should seem particularly surprising—for years now, CPAC has been in the process of transforming itself into a celebrity-centric publicity enterprise (the same could be said about American politics in general, to be fair)—but what’s unique about this year’s incarnation has everything to do with the confluence of three factors: the rising popularity of white nationalism across non-traditional media, especially on websites like Breitbart; Steve Bannon’s improbable ascendancy to the top of the White House’s labyrinthine and immensely influential power structure; and the month-old, mercurial, counterfactual, hopelessly combative tenure of the 45th president of the United States, Donald John Trump.

That being said, my main goal, arriving at CPAC—a conference for conservative activists with whom, apart from the not-insubstantial advantages of societal privilege, I share very little in common, politically and professionally—can perhaps be best summed up with a single verb: Listen. And that’s what I promise myself I’ll do, no matter how many awful things I hear.

Don’t get me wrong: I firmly believe that the new administration’s penchant for lying is a threat to American democracy; that its rhetoric has violent real-world consequences; and that its bigoted policies—against basically anyone who’s not considered white, straight, cisgendered, and male—represent a direct attack on the pluralism we’ve been working toward, in fits and starts, for centuries.

But I also think that any coalition looking to combat the forces behind Donald Trump’s startling rise will need to avoid tactics that, while effective, run the risk of sacrificing the very ideals we’re hoping to defend.

In other words: how can we respond, personally and as a group, to the very real and horrible manner in which the current administration delegitimizes all other points of view—from the press to the judiciary to the citizenry to lawmakers in both parties—without falling into the trap of dismissing, out of hand, any and all criticism of the values on which our perspectives depend?

Does this sound naïve? When is rationality just another synonym for unexamined prejudice? Could it actually be that we’re all destined, in the end, to spend eternity being tortured by a many-horned Goat-God in an afterlife of someone else’s choosing?

I hope not! In the meantime, an additional question: when it comes to Donald Trump’s presidency, who actually stands to benefit most from his policies; how will these benefits be attained; and what’s the best way to characterize the worldview of the person or people responsible for influencing his judgment?

*

At the podium of the Potomac Ballroom Donald Trump has moved to a new topic: “Our beloved military.” He’s talking about upgrades, and offensives, and strength. “Nobody will question our military might again!” he intones.

Steve Bannon is still standing only a few feet to my right. He’s watching impassively. He’s holding his glasses in his hands. He may or may not be cleaning the lenses with his fingers.

The day before, Bannon took the stage for a rare joint appearance with Reince Priebus, his White House officemate and alleged rival. For a while the two of them played up an odd-couple act—a lukewarm attempt, at best; I was seated about five rows back (as close as I am now to Trump), and I can honestly say that I wasn’t the only one in the audience who cringed—but the fireworks really got going when Bannon got to speak at length. He disparaged the media as “corporatist” and “globalist.” He talked about “economic nationalism.” And in a revelatory moment, he explained that one of his main goals will be to carry out what he calls the “deconstruction of the administrative state.” He added: “If you look at the cabinet appointees, they were selected for a reason, and that is the deconstruction.”

This last word is the one I keep thinking about as I listen to Trump’s performance—a speech that lacks any preparation, let alone an actual script—and as I watch Bannon watching the president, I’m suddenly overcome by the complete absence of a single coherent thought: a sensation that, in retrospect, is probably as good an articulation as any for the emotion I’ve been feeling, on and off, since Donald Trump was elected president.

And this is when I find myself shouting out, in a voice that’s loud enough for everyone in the ballroom to hear, the phrase I’ve been considering—but never actually thought I’d go so far as to do so.

“WAR IS PEACE!” I scream. The line is from George Orwell’s novel 1984. My voice is loud and clear. But I’m drowned out by another wave of applause. Before I can stop myself I shout it again, twice—WAR IS PEACE! WAR IS PEACE!—screaming in a manner that, in my opinion at least, the president is sure to hear.

To be clear: members of the audience have been shouting things throughout the speech. You Can Do It! a bro in a red hat intoned within the first few minutes. And later, during a disturbing tangent about violence in the inner cities, someone even bellowed Chiraq!

But after my outburst I have the distinct feeling of descending back down into the relentless cage of my body, within which I’ll now be forced to endure whatever happens next.

The affable secret service guy catches my glance; his eyes are blank and terrifying. In front of me, an older woman has turned around. She smiles. So does someone else. And at last I understand. All these people must actually think I’ve screamed something favorable: my own version of the old Reagan line Trump keeps dusting off: Peace through strength.

In the next moment I glance to my right. Steve Bannon is still holding his glasses. And while it’s impossible to say for sure, in retrospect, whether the gaze he’s training in my general direction also includes an acknowledgement of the Orwell line that everyone around me has clearly heard (and misunderstood), what I’m struck by, just then, is the sudden rapidity with which the jowly drape of his lips and chin seem to tighten back against his teeth.

Again, what I’m describing now is how it looked to me at the time. And even though I’ve come to question this experience in the days since (which is natural enough), I have to admit that if you were to ask me right then just what it was I was seeing in the face of arguably the most radical person to assume such an extensive share of American power in at least two generations, I’d respond, without hesitation: a smile of unmistakable depth.

After all, who else in the surreal theater of our modern American moment is better equipped, in terms of experience and personal ideology, to perceive the true meaning of Orwell’s line: its brilliant, irreversible decoupling of fact from reality; its simultaneous collapse of harm into safety; and most of all, its sky-dark intimation of unlimited consequence?

Not the version of Donald Trump who’s Bob Hope-ing his way through yet another presidential speech—that’s for fucking sure—at least not on a logical level.

No. The sort of power Orwell is talking about demands foresight. Before you can erase the past with the future you need to understand, with a degree of precision that true power depends on, the nature of the columns holding both apart.

Which brings us to another question—one that represents just about the limit of how far I think I’m willing to go, at least with this topic:

If the nature of your power is rooted in the act of chaos itself, then is it ever possible to limit the degree to which you unleash such a weapon on the world, especially if the means through which you exert this power—destabilization—has become at the same time your only way of influencing what happens next: a conflation drastic enough to make previously diametrical concepts like chaos and control as indistinguishable (speaking in the Orwellian sense) as something like war from something like peace?

*

Later that night, long after Trump’s speech was done—after the crowd had lingered to the opening chords of the Rolling Stones You Can’t Always Get What You Want and then departed, the day shining like a second sky in the Convention Center’s enormous glass ceiling—I would find myself on a dock in the harbor, face-to-face with The Spirit of Mount Vernon, a huge garish yacht the color of white sand.

This was just after 9pm. I was here for the Breitbart party. An old friend had gotten me on the list. Before Trump’s speech, I’d enjoyed some of the conversations I’d been having at the conference—by forcing myself to listen, a fresh chance at dialogue seemed suddenly possible—but then I watched the president of the United States swivel and lurch like a circus bear that’s spent its entire life in sad captivity, and things had been going downhill ever since.

The theme for this party was a Hawaiian luau. I arrived to find actual Polynesian dancers swaying in grass skirts and coconut bras for a galley of people that, along with the usual smattering of conservative activists, also included journalists, politicians, celebrities, and more than one white nationalist.

It was a spectacle purposefully engineered to offend, in the most blatantly juvenile way, anyone who’s ever cared about the basic moral tenets of postcolonial thinking (I lived in Honolulu myself from 2002 to 2007, which no doubt makes me especially sensitive) and now I felt an overwhelming urge to punch one these ogling young men right in his frat-boy face.

Instead, I went to get a drink. The former baseball player and famous loudmouth Curt Schilling was there. After a few more drinks I went up to him and said, “Nuke! Nuke LaLoosh! It’s me, Crash Davis. And I got a feeling you couldn’t hit water if you fell out of a fucking boat.” But he just laughed.

I saw Duane “Dog the Bounty Hunter” Chapman. And the British politician behind the Brexit movement, Nigel Farage. Though thankfully enough, Steve Bannon was nowhere to be found. And after a while I retreated to the top deck, where I talked to a reporter from the Daily Beast about Flannery O’Connor and Joan Didion and tried my best to keep myself from freaking the fuck out.

A few minutes later, as I was waiting at the bar, a young man with a smug grin and thin, restless eyes cut in front of me in line.

For a moment we glared at each other. He knew exactly what he’d just done.

“Nice jacket,” I finally said to him. “I have the same one.”

His eyes narrowed. “Maybe,” he said in a British accent. His hair was slick with gel. “The difference,” he added after a pause, “is that you’re not me. And you never will be.” He flashed a smile at a woman who’d been standing alongside him, someone he appeared to be trying to impress.

“True,” I told him. “But then, you didn’t spend all those summers at your Hitler Youth Camp to get accidentally mistaken for a guy like me.”

Late I’d find out that his name was Dan Jukes; he was Nigel Farage’s communications director—something that, at this party at least, he expected everyone to know.

At my Hitler comment the woman alongside let out a loud laugh. And then there was suddenly no way for Mr. Jukes to hide the schoolboy disappointment that swept like a blue shadow across his flat wounded face—a grimace of confusion and indignation and genuine surprise—and right then, as I gave up and drifted back upstairs, I couldn’t help but think that this young British communications director looked a lot like a youthful Donald Trump might, today, were our current president to grow up in this century instead—a young man of personal failing who nevertheless remains many decades removed from the real fate awaiting him: a destiny of physical and moral monstrosity that had been on full display, only a few hours earlier, under the bright-hot lights of an otherwise indistinct Maryland ballroom.

*

The next day, Saturday, was the conference’s last. I spent most of the afternoon typing up my notes—watching as the harbor and the city beyond disappeared beneath the advance of a thunderstorm, its rain flowing in fluid sheets off the glass of the ceiling, its lightning baring the sky with long, brilliant seams—but toward the end of the night, just as I was finishing up, I found myself in the unlikely presence of three conservative journalists: women who all, in some way or another, had worked with the one person at CPAC I still hoped to learn more about: Steve Bannon.

Each of these women had opposed Trump from the start. It was all off the record, of course, but they answered every single question I asked, allowed me to type up their responses on my computer, and offered to let me use the information for this essay—as long as I didn’t reveal their names.

What follows comes directly from my notes, which have been combined and edited at points for clarity—and to protect the identities of the women speaking.

Me: What sort of person is Steve Bannon? How would you characterize him?

Three Women: He’s amazingly clever. Crafty. Very good at long-term planning. He has the ability to create and build out a narrative over a long period of time. He has an incredibly long attention span.

Me: What does he want—what are his long-term goals?

Three Women: One way authoritarians always get power is by undermining trust in institutions. When he says he’s against the establishment, he really means longstanding institutions. Government agencies. He wants to destroy trust in the media—for him, it’s not that they’re biased, it’s that they’re illegitimate. He uses Trump’s quickness to overreact to his own ends. He’s not like the other people at Breitbart who just want to shock and get publicity and get famous. He enjoys it whenever somebody feels pain on the other side—to hurt them is his goal—and for him Breitbart was a weapon, an agent of change, a thumb on the scale to tilt things in his favor.

Me: How would you compare/contrast him to Trump?

Three Women: He met Trump through Roger Stone. They’ve known each other for years. With Trump he’s the tail wagging the dog. To an extent, Trump knows Bannon is using him. But it doesn’t matter. Trump’s goals don’t need to be remaking the system; he just wants to feel important. He’s a kid from Queens who’s never felt accepted by the New York aristocracy and has a chip on his shoulder. He’s an emotional toddler. Bannon has bigger plans. He’s authentic. He’s ruthless. He’s already as rich as he wants to be.

Me: Can you talk about why he’s so dangerous?

Three Women: The rumor is he’s begun putting things together at the state level, going around Trump. That he has ops that don’t involve Trump. He’s coalescing his power. He’s got an enemies list. People to put in demotion. List of people he’d like to exact revenge on. In my opinion, he seems okay with violence on a certain level. He believes in societal conflict. He is the most powerful man in the White House.

In the end, our conversation lasted longer than Trump’s speech. Later, after an extensive digression into the Russian intelligence dossier (its validity/lack thereof), as well as a back-and-forth on the many shady casino deals Trump has struck up over the last 30 years, a friend sent me an article from Twitter about all the recent staffing problems at the White House; in it the author went so far as to compare Bannon to a very specific type of devil: the kind that knows exactly what to whisper in its victim’s ear.

After that our conversation turned metaphorical. What kind of devil best describes the person Steve Bannon really is?

Someone started by comparing him to a standard Christian demon—the Gnostic sort who’s playing the long game: working for all eternity to find and capture the souls of earthbound humans.

Someone else thought he was more of the Loki type: a trickster-coyote sowing chaos and disorder for the simple reason that these are the very things he enjoys most.

Someone else brought up the 19th-century Russian novels. Which got me thinking about a book that’s always been dear to me and that feels especially pertinent now: Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.

Later that night, back home at last from the conference, I opened up this novel in search of a passage I’ve never been able to forget: the description, early on, of the character Woland, a distinctly Russian version of the devil come back to haunt the Soviet elite:

Afterwards, when, frankly speaking, it was already too late, various institutions presented reports describing this man. A comparison of them cannot but cause amazement. Thus, the first of them said that the man was short, had gold teeth, and limped on his right leg. The second that he was enormously tall, had platinum crowns, and limped on his left leg. The third laconically averred that the man had no distinguishing marks. It must be acknowledged that none of these reports is of any value.

First of all, the man described did not limp on any leg, and was neither short nor enormous, but simply tall. As for his teeth, he had platinum crowns on the left side and gold on the right. He was wearing an expensive grey suit and imported shoes of a matching color. His grey beret was cocked rakish over one ear; under his arm he carried a stick with a black knob shaped like a poodle’s head. He looked to be a little over forty. Mouth somehow twisted. Clean-shaven. Dark-haired. Right eye black, left eye—for some reason—green. Dark eyebrows, but one higher than the other. In short, a foreigner.

–Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita

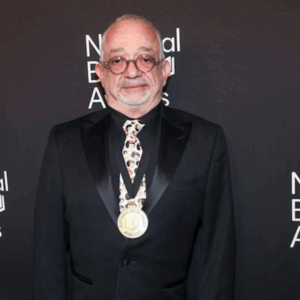

Timothy Denevi

Timothy Denevi’s most recent book is Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism.