The Cultural Encyclopedia of Mushrooms That We Need Right Now

From Lewis Carroll to John Cage, the Mycelium Are Everywhere

The following entries are from Lawrence Millman’s encyclopedia of fungal lore, Fungipedia, a compendium of all things mushroom; with illustrations by Amy Jean Porter.

*

ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Delightfully surreal 1865 novel by the Reverend Charles Dodgson, otherwise known as Lewis Carroll, which features perhaps the most famous mushroom in all of literature. On top of that mushroom is seated an almost equally famous hookah-smoking caterpillar. “One side [of the mushroom] will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow smaller,” the caterpillar observes to the heroine, Alice, who, being of an adventurous nature, decides to test this seemingly peculiar remark. It turns out to be correct.

It’s likely that Carroll learned about the mushroom in question, probably the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), from reading English mycologist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke’s 1860 book The Seven Sisters of Sleep. This book describes the effects of eating the fly agaric as follows: “Erroneous impressions of size and distance are common occurrences . . . a straw lying on the road becomes a formidable obstacle to overcome.” It should be noted that the first illustrator for Carroll’s own book, John Tenniel, depicted not a fly agaric but a generic mushroom. Carroll’s own illustration for Alice’s Adventures Under Ground looks like a generic mushroom, too.

Alice evolved to become a popular countercultural figure in the 1960s. For example, Grace Slick’s song “White Rabbit” includes these well-known lines: “You’ve had some kind of mushroom, and your mind is moving slow / Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know.” Grace herself certainly knew.

*

CAGE, JOHN (1912-1992)

Composer–performance artist who tried to emancipate music from its, to him, turgid system of notes by using goose quills, pressure cookers, old wine bottles, rubber ducks, ice cubes, sneezes, and silence in his compositions, which have been described as being akin to a circus taken over by its clowns.

Cage often referred to the fact that the word “mushroom” precedes “music” in dictionaries. In the words of writer David Rose, “the mycological and musical are revealed by Cage as parallel universes.” Indeed, the chance or indeterminate feature of Cage’s music may owe some of its inspiration to mushrooms, which seem to appear or not appear owing to their own idiosyncratic whims.

Cage helped establish the New York Mycological Society in 1962. He also taught a course in mushroom identification at the New School in New York City. Until late in life, he made his living not by his music but by collecting and selling mushrooms to upscale restaurants in New York.

Cage’s attitude toward mushrooms was often worshipful. Indeed, he wrote a poem that ends with this statement about them: “So far they’ve remained just as mysterious as they ever were.” Less worshipful, perhaps, was his belief that if you play a recording of a Beethoven quartet for a fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), it will become a prime edible.

*

FICTION

Mushrooms figure prominently in fiction not only because they can be used to kill another person, but also because they sometimes look like works of fiction themselves. In addition to Alice in Wonderland, here are a few examples:

· “The Purple Pileus,” a short story by H. G. Wells in which a timid shopkeeper with an odious wife uses a hallucinogenic mushroom to improve his life

· Babar the Elephant, a children’s book by Jean de Brunhoff in which the King of Elephants dies from eating a poisonous mushroom

· Anna Karenina, a novel by Count Leo Tolstoy in which children go from being unruly to joyous at the prospect of hunting mushrooms, and a man eager to propose to a woman ends up identifying mushrooms with her instead

· Journey to the Center of the Earth, a novel by Jules Verne that includes a journey through a forest of giant subterranean mushrooms

· “The Voice in the Night,” a horror story by English writer William Hope Hodgson that features a man shipwrecked on an island of malevolent fungi

· Stowaway to the Mushroom Planet, a children’s book by Eleanor Cameron in which two boys take a spaceship to a planet called Basidium

· The Documents in the Case, a mystery novel by Dorothy Sayers where mushrooms are employed as a murder weapon—a good example of what happens when a fiction writer seems to know nothing about mycology

*

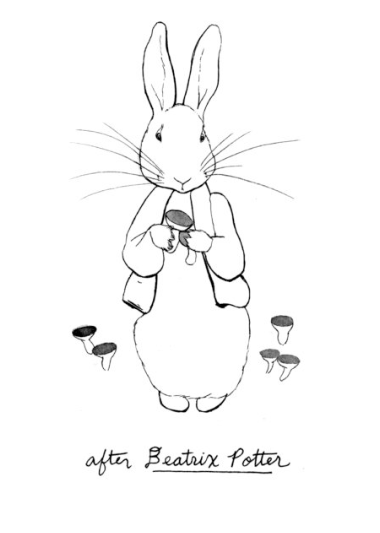

POTTER, BEATRIX (1866–1940)

An Englishwoman who possessed an interest not only in mycology but also in geology, entomology, and archaeology. She may have been the first person to propose that lichens are the marriage of an alga and at least one fungus. She also made exquisite illustrations of mushrooms and very precise drawings of their spores, although she admitted that she “could not find the courage” to draw stinkhorns.

Ms. Potter couldn’t present a scientific paper titled “On the Germination of Spores in Agaricinaceae” to the Linnaean Society in London in 1897 because, as a woman, she couldn’t attend the proceedings in order to read the paper. Since she wasn’t allowed to do serious mycological work for the same reason, she began writing as well as illustrating children’s books about bunnies, badgers, and cute frogs in breeches. The best known of these books is, of course, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published in 1901.

*

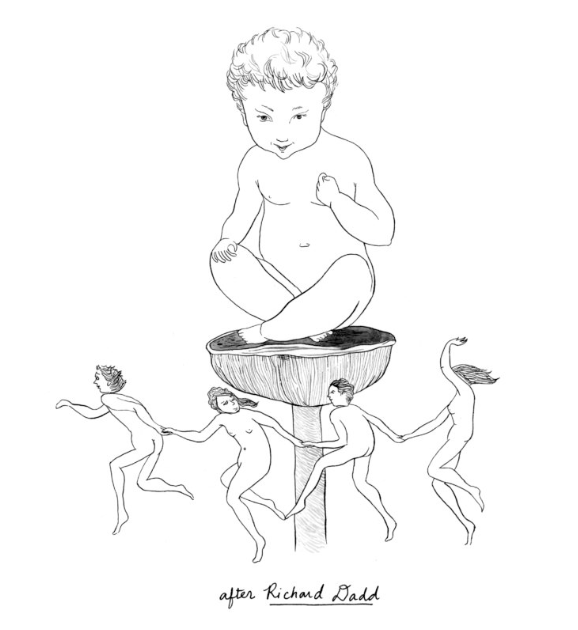

PUCK

Not the chef Wolfgang Puck, who has created numerous mushroom dishes such as his justly acclaimed farro risotto with wild mushrooms, but the mischievous supernatural fairy or sprite of English folklore as well as a prominent character in Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

In paintings and illustrations, especially Victorian ones, Puck is frequently depicted as sitting on a mushroom, which would seem to indicate that the English used to associate mushrooms with mischief as well as the supernatural. In a Victorian production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he rose onto the stage atop a mechanical mushroom; and in a striking painting by the artist Richard Dadd (1817–1891), a Puck with an extremely puckish grin on his face is squatting on top of a mushroom, and a number of naked men and women are dancing around him as if he were a deity on a throne.

In the past, the English often attributed Puck’s origin to Ireland. After all, the mischief-making abilities of the Irish far surpassed their own . . . or so they believed.

*

Schobert, Johann (ca. 1735–1767)

A German of Silesian composer who shouldn’t be confused with the somewhat better known, not to mention considerably better, Austrian composer Franz Schubert. Nowadays Schobert is more famous for the manner of his death than for his music.

Although the young Wolfgang Mozart admired Schobert’s music, Mozart’s father, Leopold, thought that the composer’s talent was, as Leopold put it, “low.” But however low Schobert’s musical talent was, his ability to identify mushrooms was even lower. At Le Pré-Saint-Gervais outside Paris, he picked a batch of mushrooms and brought them to a restaurant so the chef could cook them. “Poisonous,” the chef said. Schobert left in a huff and brought them to another restaurant, whose chef said the same thing. Whereupon Schobert went home and cooked the mushrooms himself. The species was probably the death cap (Amanita phalloides), with the result that Schobert, his wife, and all but one of his children departed this world.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Fungipedia: A Brief Compendium of Mushroom Lore by Lawrence Millman. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Lawrence Millman and Amy Jean Porter

Lawrence Millman is a mycologist and author of numerous books, including Our Like Will Not Be There Again, Last Places, Fascinating Fungi of New England, and At the End of the World. He has done mycological work in places as diverse as Greenland, Honduras, Iceland, Panama, the Canadian Arctic, Bermuda, and Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he has documented 321 different species.

Amy Jean Porter is an artist, illustrator, and naturalist. Her illustrated books include Of Lamb and The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook, and her artwork has appeared in such publications as McSweeney’s and The Awl.