The Comma Queen and

the Internet’s Copy Chief on What Matters to a Copyeditor

Mary Norris and Benjamin Dreyer Talk Grammar and Style

We asked Mary Norris, The New Yorker‘s “comma queen” and author, most recently, of Greek to Me, and Benjamin Dreyer, copy chief of Random House and author of Dreyer’s English, about their love of editing, the mistakes people make, and whether or not this intro has too many commas. (It probably does, doesn’t it?)

*

When did you first become interested in studying grammar?

Mary Norris: I was always good at English—the nuns started drilling us early in the misuse of “like” for “as”—and we spent a few days diagramming sentences. I had a formative teacher in seventh grade, Mr. Smith, who made spelling interesting by having us write stories that employed as many of that week’s spelling words as possible. But this is not grammar. Strictly speaking, grammar is case (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative) and agreement (plural verbs for plural nouns) and antecedents and other stuff with scary names. I learned grammar when I studied German in my senior year of college. Too bad I was taking the course pass/fail, because I aced it.

Benjamin Dryer: To be perfectly honest, I’ve never been interested in studying grammar. I certainly recall being taught which one was the subject and which one was the predicate, and by the time I graduated from elementary school I knew, more or less, the difference between an adjective and an adverb, but grammar held no fascination for me, and I’m happy to confess that I don’t know how to diagram a sentence. What I was interested in was reading, voraciously, so that’s what I did and have done, my whole life. By the time I wandered into proofreading and then copyediting, I’d cultivated a good ear for what worked and what didn’t work on the page—which is not quite the same thing as knowing what’s right and what’s wrong—but I certainly realized that if I was going to do this sort of work for a living, I’d need to have some knowledge to back up my instincts. So truly, it was only in my thirties that I began to read up on grammar. I still firmly believe that copy editors need only enough grammar to get them through the demands of their particular manuscripts; being a grammarian is entirely beside the point. Or to put it another way, grammar is part of what you do as a copy editor, but only a part. That said, it’s fun to know about the subjunctive, so I’ll concede that particular pleasure.

*

In your opinion, what is the number one grammar rule that everyone should know?

BD: As much as some people continue to predict the imminent death of the word “whom,” it seems to me, nearly 30 years into my publishing career, to be thriving just fine. People would do well to learn the difference between “who” and “whom,” and “whoever” and “whomever.” And if you can conquer the difference between “I” and “me,” or “they” and “them,” that shouldn’t be so hard. That said, always better to use a “who” where a “whom” might be considered correct than to use a “whom” where a simple “who” is all that’s called for.

MN: You can have friends or you can correct people’s grammar.

*

What’s a common mistake people make?

BD: If we’re speaking of garden-variety errors, the most common error I’ve observed that manages to get past any number of sets of expert eyes and wind up printed in books is the use of “lead” where “led” is meant—that is, the past tense of the verb “to lead.” If we’re speaking of a larger, more overarching mistake that writers make, it’s not taking the time to read their work aloud as they’re refining and editing it. If they did, they might easily find all sorts of errors and infelicities that they could themselves solve, leaving their copy editors to work on more abstruse (but important) stuff.

MN: They mistake the apostrophe for a piece of punctuation when it is a spelling issue. The confusion between lie and lay is embedded in the language by now, such that people who know better go out of their way to use the wrong word. People also confuse grammar with usage. I was taught that “masterly” is the right word for something that has been done expertly, in a wonderful way, and cringe when I see a book described as “masterful,” which means powerful and forceful. It’s a distinction someone made up. I consider it a useful distinction and try not to cringe anymore.

I’ve heard people use “antepenultimate” to mean something even more ultimate than ultimate: ultimate super plus, like extra-high octane gas. Ultimate means last. “Pen” is the suffix for almost, so penultimate is almost the end. (Peninsula is “almost an island.”) Antepenultimate is before (ante) the second-last, or third from last. So it’s not as good as ultimate.

*

How would you describe your work place’s style when it comes to written pieces?

MN: The term “house style” refers to mechanics: use of italics or quotes for titles, adherence to the serial comma, how to handle numerals consistently. For example, it’s house style at The New Yorker to write out round numbers, but increasingly we have come to regard all numbers as round—or so it would seem. Numerals jump off the page; numbers written as words lie on the page and don’t interrupt the flow. New Yorker house style is for readers who have the leisure to savor what they read.

The other kind of style is a writer’s personal style, her way with words and sense of the sentence. Copy editors do not meddle with a writer’s personal style. Sometimes we might not like something—for instance, the use of “they” when a singular pronoun is called for—and we can make a suggestion, but if the writer feels strongly that the suggestion isn’t in her voice, then it’s more important to let the writer have her voice.

BD: One thing that pleases me about working at a book-publishing house rather than at a newspaper or magazine is that I don’t have to participate in, or live up, a complex and complicated house style. The house style of Random House is that we don’t have a house style—well, except for the series comma, which we take as much delight in imposing as newspapers tend to take delight in deleting. But the real house rule is that every book gets the copyedit it needs, a copyedit that attends to a particular author’s particular style.

__________________________________

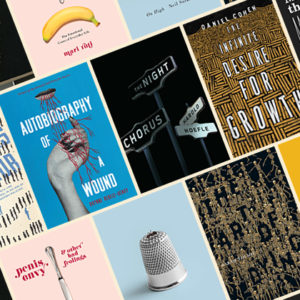

Benjamin Dreyer is vice president, executive managing editor and copy chief, of Random House. He has copyedited books by authors including E. L. Doctorow, David Ebershoff, Frank Rich, and Elizabeth Strout, as well as Let Me Tell You, a volume of previously uncollected work by Shirley Jackson. He is the author of Dreyer’s English. A graduate of Northwestern University, he lives in New York City.

Mary Norris is the author of Greek to Me and the New York Times bestseller Between You & Me, an account of her years in The New Yorker copy department. Originally from Cleveland, she lives in New York.