The Biggest Literary Stories of the Year: 50 to 31

From Anne Carson Going Viral to the End of the Manuscript Thief Saga

And yet again, we’ve reached the end of a long, bad year. As is now our custom, for the sake of posterity, and probably because we’re masochists, starting today, we’ll be counting down the 50 biggest literary stories of 2023, so you can remember the good, the bad, and all the literary cool girls we met along the way. Join us:

50.

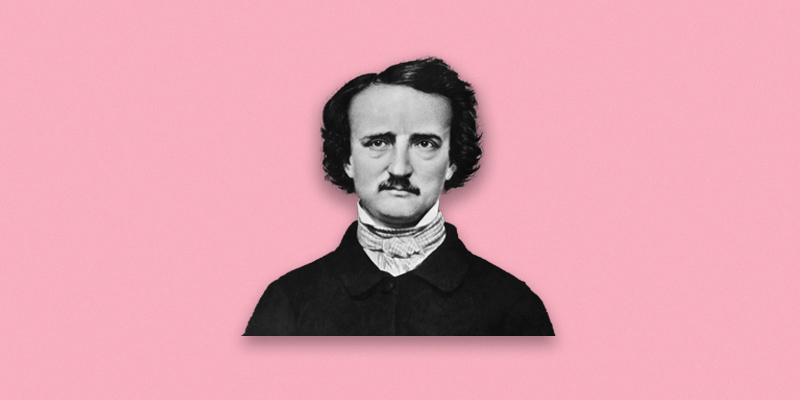

Edgar Allan Poe starred in the Eurovision Song Contest.

Competition was fierce at this year’s Eurovision Song Contest, but I was particularly partial to Teya & Salena’s “Who the Hell is Edgar?”, which featured Edgar Allan Poe’s visage looming over the singers on stage and my favorite group dance since “Single Ladies.” Go ahead, give it a listen and see if you can resist singing “Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe” ad infinitum. –Eliza Smith, Lit Hub special projects editor

49.

Anne Carson re-entered The Discourse.

There was no prior announcement, but an assessment took place this summer on the internet of our collective worth, a kind of Internet Speed Test for our souls.

On June 5, New Yorker writer Hannah Williams posted a screencap of Anne Carson’s 2017 POEM “Saturday Night As An Adult,” with the caption: “Think about this a lot” (editor’s note: the choice not to include a period perhaps emphasizing the open-ended nature of this thought). The poem captures a series of disappointments at a dinner out with second- and third-tier friends.

https://twitter.com/hkatewilliams/status/1665763486549307392

Like a weather balloon lofted into the sky, or a chubby wombat awakening with a new honing beacon attached to its ankle and rushing off into the bush, the scene was now set for The Study to begin.

By 10 a.m. EDT, June 7, Williams’ tweet had been retweeted 928 times, quote-tweeted 583 times, and liked almost 10,000 times, indicating 928 instances of people finding an outsized resonance in the original tweet, and 583 instances of people hoping to correct the discourse, which ran quickly off the rails into a series of what Carson might term “yell factions.”

Critiques of the short poem about getting dinner at a noisy restaurant and finding bones in your fish fillet ranged from “kill Anne Carson?” to “wow that’s crazy has the author ever thought about letting joy into their life.” Generally speaking, a common theme was “can’t we just have a nice dinner here on Twitter, Anne Carson?”

Critiques of the critiques argued for the salvaging of context amid anthropogenic context-decline. I note, for example, Carson’s formal choices around line breaks and choice in the poem to use the royal “we” to engage the reader (seemingly, it worked). The viral moment came as the government issued a Code Red for air quality across much of the Eastern U.S., and as scientists warned that Arctic ice-melt was approaching a tipping point.

“I think it’s about the Michael Cera movie,” said the internet in utter earnestness.

The conversation continued into June 7, showing no signs of letting up despite the orange skies over Twitter hotspot New York City.

“Anne Carson should go to therapy and work on setting boundaries” offered Lauren Oyler in presumed disappointment at the level of discourse we have to work with here.

Anne Carson should go to therapy and work on learning to set boundaries

— Lauren Oyler (@laurenoyler) June 6, 2023

As to Anne Carson herself, the prolific Canadian poet and classicist appears not to be on Twitter at all (you’ll have to follow @carsonbot instead, I suppose, or read this appreciation for Autobiography of Red).

In a good appraisal of the aptitude Carson’s poetry has for Twitter, Dirt’s Terry Nyugen wrote, “There seems to be a Carson verse suitable for any ruminative occasion (“Is it a god inside you, girl?”) or random outcry (“[scream] [scream] [scream] for my ruined city”). A line from An Oresteia can be repurposed into an ecstatic anti-work mantra: “Gods! Free me from this grind!” No other contemporary poet inspires such a rabid rush of retweets.”

In other words, this won’t be the last time we fail a simple comprehension test.

It’s possible that even Anne Carson has had enough of the Anne Carson discourse, writing in a new poem “No You May Not Write about Me” in the London Review of Books that:

I should go in. I go in. I say, You are the worst thing I know I

can’t breathe around you the world is more than this I am more than you put on your

black coat we’re going out. We go out.

With prescient timing, Carson obtained Icelandic citizenship last year, all the better to escape the encroaching QT-storm. –Janet Manley, Lit Hub contributing writer

48.

Everyone on the Booker shortlist was named Paul.

Okay, sure, it was only 50% of the people on the Booker shortlist, but that’s still a lot of people named Paul. And surprise, surprise, one of them won. (This year, the bookies called it.) Read an in-depth feature on Paul Lynch, the Paul in question, here. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub managing editor

47.

Tim O’Brien published his first novel in 20 years.

In October, Mariner Books published America Fantastica, Tim O’Brien’s first novel in twenty years. Arguably still best known for his 1990 story collection The Things They Carried, O’Brien’s new novel is a madcap road trip novel full of terrible people in a Trumpian America obsessed with “mythomania.” But in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, O’Brien said it would be his last, “I think I’m probably done. I will be 77 in two weeks. I’ve got bad carpal tunnel [syndrome]—really, really, really bad. Typing is just a chore. I’ve got to peck it out with one finger. God, writing a novel that way—it’s hard to imagine doing that. I can’t 100% say I’m not going to write another book, but the odds are really, really slim.” To be fair, he said that about the last one too, so here’s hoping. –Emily Firetog, Lit Hub executive editor

46.

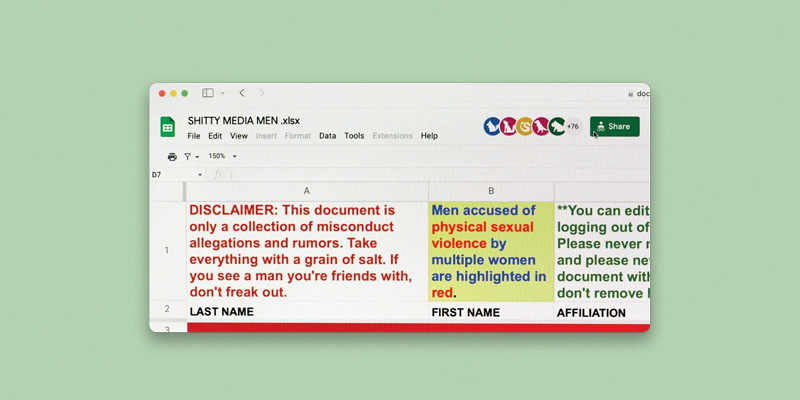

Stephen Elliot settled his defamation lawsuit against Moira Donegan.

This endless debacle may now hold the record for most years appearing on this list: news of Moira Donegan’s “Shitty Media Men” spreadsheet first circulated in late 2017, but became an international #MeToo sensation when Stephen Elliot decided to sue for defamation in 2018:

In a move guaranteed to offend pretty much everyone, including other people who were named on the list, Elliott in October filed a federal lawsuit against Donegan claiming defamation and seeking $1.5 million in damages along with information that would reveal who anonymously added to the spreadsheet or shared it.

Well, five years later, after much public whingeing from Elliot, he has settled his lawsuit for something in the six-figure range. It’s hard to say for sure, but given the overwhelming amount of support for Donegan during the trial—including free legal representation—one hopes that she hasn’t had to spend a dime on any of this. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub editor in chief

45.

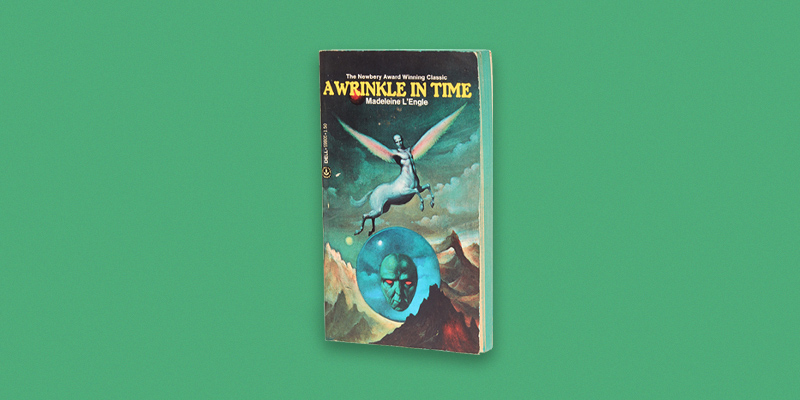

Internet sleuths wondered—and then discovered—who was behind the classic 1976 cover for Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time.

You probably recognize the iconic cover of the 1976 Dell edition of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, but have you ever wondered who illustrated it? This spring, artist Michael Whalen asked Twitter for help figuring it out, but for a while it looked like the mystery would be as unfathomable as the cosmos.

Finally, Amory Sivertson, the co-host and senior producer of the podcast “Endless Thread,” figured it out, as Amanda Holpuch reported in September. The artist’s name is Richard Bober, and he is also the creator of many other weird artworks, for Dell paperbacks and otherwise. The internet was useful for once! –ET

44.

44.

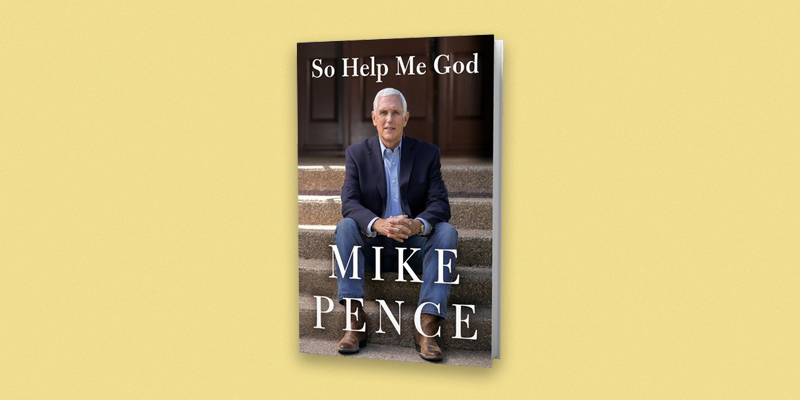

Mike Pence’s book became a best-seller . . . because his PAC spent $91,000 buying copies.

It is a time-honored tradition in American politics to beg, borrow, steal, lie, and otherwise outright cheat basically whenever possible. When it comes to stakes, best-seller lists might be relatively small potatoes when compared to, say, the authoritarian overhaul of our rickety democracy—but it turns out the main reason Mike Pence’s memoir hit the bestseller list is because he spent $91,000 of his PAC’s money to get it there. You’d think that would’ve earned a dagger on the list, or perhaps that the NYT and other list-makers would change the rules so that these bulk buys wouldn’t count! You would think. –Drew Broussard, Lit Hub contributing editor

43.

A new forensic study found that Pablo Neruda was poisoned.

Officially, Pablo Neruda, the Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet who wrote that love poem you like so much, died on September 23, 1973 from prostate cancer, coincidentally just shy of two weeks after Pinochet overthrew the government of Neruda’s (democratically elected) friend, President Salvador Allende, in a military coup backed by the US. Not surprisingly, there have always been rumors that Neruda was murdered for political reasons, and this year, 50 years after the poet’s death, forensic experts have confirmed once and for all that he was poisoned, or at least that the toxin clostridium botulinum was present in his body when he died.

“We now know that there was no reason for the clostridium botulinum to have been there in his bones,” Neruda’s nephew, Rodolfo Reyes, told the Spanish news agency Efe. “What does that mean? It means Neruda was murdered through the intervention of state agents in 1973.” –ET

42.

Maggie Tokuda-Hall refused to remove references to racism from her children’s book.

Back in April, Maggie Tokuda-Hall tweeted a story that those of us who fondly remember our Scholastic book fair days were horrified to learn: Scholastic’s educational division had approached Tokuda-Hall about licensing her book, Love in the Library, for use in classrooms—but the offer was contingent upon Tokuda-Hall removing references of racism from her author’s note. Originally published by Candlewick, the book for six- to nine-year-olds was inspired by Tokuda-Hall’s grandparents, who met and fell in love in an incarceration camp that held Japanese Americans during World War II.

The author’s note introduces readers to the real-life Tama and George, and references “the deeply American tradition of racism” that continues today in the police murders of Black people, Muslim bans, children in cages at the border, and so on—all of which got a big, red strike-through from Scholastic.

Tokuda-Hall declined Scholastic’s offer and sounded the alarm, and a public outcry ensued. Scholastic offered to publish the book with the original author’s note, an offer Tokuda-Hall refused, and the company paused production of the AANHPI narratives collection that Love in the Library would’ve been part of in order to evaluate their practices. One has to hope Scholastic will learn from the (extraordinary) mistake… but the top ten literary stories of the year reports otherwise. Stay tuned. –ES

41.

Michel Houellebecq filmed a porno . . . then had the Dutch courts suppress it.

It would be hard to find a literary news story in 2023 that was a greater source of delight to me, one of the few Lit Hub staffers who genuinely liked Michel Houllebecq’s early novels (he lost me with The Map and The Territory). As I wrote in March, somewhat breathlessly:

…defiantly unctuous French novelist-cum-provocateur Michel Houellebecq is having second thoughts about his whole “xenophobic libidinous creeper toad” thing—at least when it comes to doing it on camera with attractive young Dutch women. Allow me to explain.

According to Dutch art collective KIRAC (Keeping It Real Art Critics), the idea for the “experimental porn” originated at a Paris dinner party in which Houllebecq’s wife, Qianyun Lysis, suggested to KIRAC co-director Stefan Ruitenbeek that her husband get naked in front of the camera to “counteract his gloom.” Houellebecq and Lysis were familiar with KIRAC because of an earlier film by the collective, Honeypot, in which Dutch extremist Sid Lukkassen becomes entangled with a comely young leftist.

Unsurprisingly Ruitenbeek leapt at the opportunity to film sexy times with the increasingly misogynistic, xenophobic Houellebecq. Lysis also told VICE that she told Ruitenbeek he’d “have to turn [her husband] into a porn star.”

So far so good! I guess! Maybe. Ugh.

Houellebecq went to Amsterdam just before Christmas and proceeded to hang out on a hotel bed and drink wine in his pajamas, waiting for one of the “many girls in Amsterdam who would sleep with the famous writer out of curiosity.” Amidst the hedonist reveries Houellebecq signed a release waiver in which the only limitation on filming was that “his face and genitals would not appear on screen at the same time.”

A few days after arriving in Amsterdam, though, Houellebecq walked off the set, accusing Ruitenbeek of “gutter journalism” and citing “radically opposed” artistic conceptions of the film. This, of course, was after Houellebecq slept with KIRAC collaborator Jini van Rooijen. According to Ruitenbeek, “It was incredible, they did all kinds of positions. He’s very good in bed.”

Fast forward a few months and Houellebecq has made attempts in both France and the Netherlands to block the film’s trailer and release, claiming, among other things, that it will damage his honor (lol). Houellebecq’s petition was denied in France, and only yesterday a Dutch judge declared that KIRAC has every right to distribute the film, despite the novelist’s protestations that he was “depressed at the time of signing the agreement and had drunk several glasses of wine.”

And no, I have not yet watched the movie, and likely never will. –JD

40.

Gabrielle Zevin’s best-selling novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow sparked a debate about credit in fiction.

Gabrielle Zevin’s novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow which was published in July of 2022, stayed on the New York Times best-seller list for 33 weeks and sold more than a million copies globally. But earlier this year it sparked a debate about credit in fiction. TaTaT is a story about two video game developers and has a robust “Notes and Acknowledgments” section where Zevin “notes instances in which she referenced real games… and names half a dozen games that inspired a chapter called ‘Pioneers’ as well as their designers.” Missing from those acknowledgments is Brenda Romero, a game designer who read the book and saw the idea and structure of her board game Train, which she developed at MIT, is reflected in a key point in the book:

Regarding Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, my uncredited work is in the book. “Solution” is, by the author’s own admission, a take on my game Train. She uses the same theme, gameplay patterns, releases the game at the same location (MIT) … more

Article continues after advertisement— Brenda L Romero (@br) March 22, 2023

As the Washington Post explains, “In the novel, Sadie designs “Solution” as an MIT student in the 1990s. It’s a “Tetris”-like video game taking place “in a nondescript black-and-white factory that made unspecified widgets.” The player earns points for each widget but is constantly interrupted by a text bubble, which offers information about the factory in exchange for points. Through this feature, players eventually learn that the factory belongs to the Third Reich and that they can choose to slow, or stop, making parts. High scorers who dismiss the bubble eventually see a message calling them a Nazi. “The idea of ‘Solution’ was that if you won the game on points, you lost it morally,” Zevin writes in the novel. “Solution” bears a strong resemblance to Train, a game Romero created in 2009.”

Todd Doughty, Knopf Doubleday’s senior vice president for publicity and communications, issued a statement saying: “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is a work of fiction and when crafting a novel, every author draws from the world around them. As Gabrielle Zevin publicly stated in last year’s Wired interview, Brenda Romero’s undistributed board game, ‘Train,’ which Zevin has never played but was aware of, served as one point of inspiration among many for the novel, including books, plays, video games, visual art and locales.

Do fiction writers need to cite their inspiration? Or is this more a case of stealing an idea? At least readers now know about Train. –EF

39.

Cat Person ruined “Cat Person.”

Ah Cat Person: The Movie, was there ever any real hope for you? The ill-advised Emilia Jones- and Nicholas Braun-starring adaptation of Kristen Roupenian’s mega-viral 2017 New Yorker short story premiered at the Sundance Film Festival way back in January, and while initial reviews weren’t quite dead-on-arrival bad (nothing will ever top the The Goldfinch in that department), they were still pretty rough. By February, the writing was on the wall for Susanna Fogel’s film, and by the time Cat Person was released to the great unwashed masses in October, all remaining interest in the phenomenon had seemingly dissipated: the film limped to (a lot) less than half a million dollars (on a reported $12 million production budget) at the box office, and then disappeared. By the sounds of things, Cat Person wasn’t aided by its tacked-on horror movie ending, which The Guardian called “a bafflingly silly misjudgment with any of that previous, far scarier, unease replaced with in-your-face violence.” Meow. –DS

38.

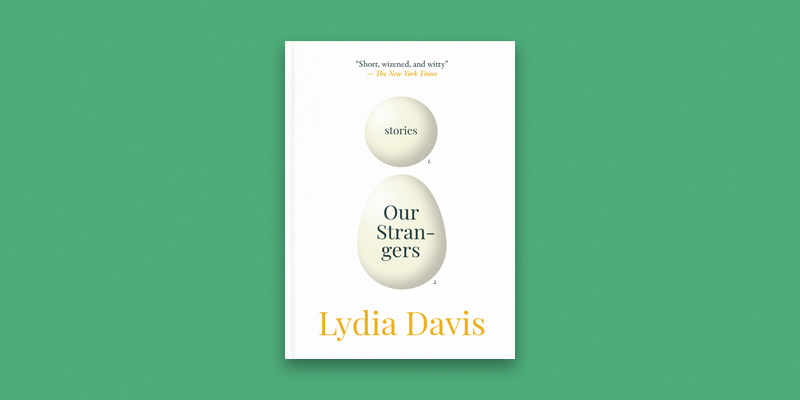

Lydia Davis published a new book, only to be sold at indie bookstores.

New work from Lydia Davis is always cause for celebration—but this new collection of stories isn’t just a book. It’s also an experiment: if a book is published without being distributed to Amazon, will it still make a sound? (It’s being distributed only to independent bookstores and through our friends at Bookshop.org)

It’d be a worthy effort even if the book was second-rate—but happily, the collection is a delight through and through. Some of the stories are barely as long as their titles, many of them are lightly off-kilter in one way or another, and I found it best read like a poetry collection: dip in, dip out; read one every night before bed for a week, then put it aside and pick it up again later. A good read and a good cause—an experiment worth investing in. –DB

37.

Granta published a new list of the Best of Young British Novelists and not all men were upset.

Once a decade since the year of our Lord 1983, the good people at Granta magazine have anointed a new crop of emerging writers to watch out for in the future. It dubs these precocious wordsmiths the “Best of Young British Novelists,” and many of the chosen have gone on to carve out nice little careers for themselves. The first BoYBN class included Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Pat Barker; the second had Jeanette Winterson, Ben Okri, and Hanif Kureishi; and the 2003 group featured Zadie Smith, David Mitchell, Rachel Cusk, and Hari Kunzru. Not bad, eh? Seems like they should keep producing these lists, right? Wrong! The latest incarnation, which arrived in April and featured only four red-blooded British male novelists, prompted this New Statesman article by Will Lloyd, in which the author asked the question that has kept many of us awake at night these past few years: “How did male literary novelists become uncool?”

Lloyd didn’t furnish us with a definitive answer, but he did murder poor old John Green (“Green was neither cool, nor was he sexy … Nobody could even be bothered to be rude about him”) on his way to this discourse-igniting conclusion:

Inevitably, it all comes down to status. The decline of male literary fiction is not down to a feminist conspiracy in publishing houses, nor is it evidence that the novel itself is in decline. Reality is simpler. If men cannot dominate the literary landscape, cannot walk into lists like Granta’s, deservingly or not, they will look for other landscapes to colonize.

I presume he’s referring to either Mars, the Metaverse, or the lost city of gold, but only time will tell. –DS

36.

BU’s Center for Antiracist Research, led by Ibram X. Kendi, was dismantled.

In the year that Donald Trump was elected President, Ibram X. Kendi won the National Book Award in Nonfiction for Stamped from the Beginning, which along with other endeavours like the 1619 Project, brough to the fore once again the notion that America’s foundation and entire history is inseparable from slavery. It’s fair to say that his 2019 book, How To Be An Antiracist, made him a bona fide star, and the protests across America in 2020 following the murder of Floyd George created a new moment of reckoning for public and private institutions, with corporations and colleges alike taking steps to show they were fighting racial injustice.

It was in this context in 2020 that Boston University announced that Kendi was to be appointed the inaugural director of the Center for Antiracist Research. The Center raised, by some accounts, up to $54 million and had a staff of over forty, with funding coming from the non-profit sector, the corporate sector, and individual donors. The Center would combat racism by, amongst other things, conferring a masters degree and an undergraduate major in antiracist studies.

But by September 2023 it was announced that over half of the Center’s staff would be laid off, that $30 million of the remaining funding would be placed in an endowment, and that the Center would refocus its attention to offering nine-month academic fellowships, a model familiar throughout the country. Of course, the right was quick to pile on, spouting all kinds of familiar racist tropes, but Kendi came in for some heavy criticism from former colleagues, who cited a culture of mismanagement, and fellow intellectuals, who found fault in Kendi’s aims and approaches from the beginning. Writing in the New Yorker, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor pointed out that Kendi’s individual approach, where personal work can lead someone to become an antiracist, seemed more likely to assuage liberal guilt than bring about systemic change in the way that Dr Martin Luther King Jr, Angela Davis or James Baldwin had championed. As Taylor noted, perhaps “Kendi’s decision to simply sit on much of his funding, as what seems like a kind of anti-racist rainy-day fund, deserves more explanation than a murky idea that academic fellowships can contribute to the effort to combat racial injustice.” –SR

35.

Anthony Broadwater, after being exonerated for the rape of Alice Sebold, received a $5.5 million settlement from New York State.

After being wrongly convicted and spending 16 years in prison for the 1982 rape of Alice Sebold, author of the memoir Lucky (which describes the attack and ensuing court case) and The Lovely Bones, Anthony Broadwater—who was exonerated in 2021—was granted a $5.5 million settlement from New York State. The New York Times reports that Sebold made the following statement: “No amount of money can erase the injustices Mr. Broadwater suffered. But the settlement now officially acknowledges them.” (As of 2021, Scribner no longer publishes Lucky.) –ES

34.

Hanif Kureishi dictated poignant daily dispatches from his hospital bed.

On January 6th, Hanif Kureishi (The Buddha of Suburbia) shared with his Twitter followers that he’d suffered a grievous injury several days earlier, when he collapsed in Rome and regained consciousness without the use of his arms or legs. “It occurred to me then that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body,” he wrote in the dictated Twitter thread. “I had become divorced from myself. I believed I was dying. I believed I had three breaths left.”

Kureishi continued to dictate to his family (of whom we get glimpses as well); his missives—poignant and funny, beautiful and candid—proved incredibly popular and eventually turned into a Substack newsletter called The Kureishi Chronicles. He writes about sex and drugs and music, his trepidation over returning to an able-bodied world, and of course writing and reading (among a smattering of other topics). A memoir, Shattered, that will expand further on the material, is planned for 2024—a major publishing event, to be sure. –ES

33.

Lit Hub made the Pulitzers change the rules (sort of).

In August we published an open letter to the Pulitzer Prizes from almost three hundred writers imploring the prize to “update your requirements for the Pulitzer Prize to include the work of our peers who through accidents of geography, of violence perpetrated on our lands, and the personal familial reckonings with survival, have come to have or have been born into a mixed or undocumented status.” (Many people in the literary community first learned that in the categories of Fiction, Biography, Memoir, Poetry, and General Nonfiction, the Pulitzer Prize required authors to be United States citizens from Javier Zamora’s op-ed piece, It’s Time for the Pulitzer Prize for Literature to Accept Noncitizens.)

After our letter, the Prize reached out to let us know that they had been discussing the issue since last year and planned to address the issue at their fall meeting. In September, the Pulitzer Prize Board announced it had decided to expand eligibility for the Books, Drama and Music awards beyond the current U.S. citizenship requirement to include permanent residents of the United States and those who have made the United States their longtime primary home. The amended criteria will go into effect beginning with the 2025 awards cycle, which opens in the spring of 2024. “This expansion of eligibility is an appropriate update of our rules and compatible with the goals Joseph Pulitzer had in establishing these awards,” the Board said in a statement from co-chairs Prof. Tommie Shelby and Neil Brown. Did Lit Hub change the rules of the Pulitzer Prizes? Well, I don’t think we didn’t help! –EF

32.

Feminists bookstores came back.

One heartening trend as conservative lawmakers and “concerned parents” attempt to ban books about anyone who isn’t straight, white, Christian, and entirely without sexual parts or urges: Feminist bookstores are experiencing a welcome revival. Ms. reported that the number of self-identified feminist bookstores in the country has more than doubled since 2017.

At a moment when the rights of women, LGBTQ+ and BIPOC people are under assault and book bans are reaching a fever pitch, vibrant activist communities are once again coalescing in and around feminist bookstores.

Ms. highlighted business thriving as both bookstores and community spaces, particularly in states where freedom to read is the most imperiled—Burdock Book Collective in Alabama, Violet Valley in Mississippi, and the recently opened Eleanor’s Norfolk in Virginia. Once again, indie bookstores continue to be much-needed beacons of hope in a bleak, bleak national landscape! –JG

31.

The manuscript thief saga came to an end.

Remember the frankly dazzling series of heists that had the literary world on edge? No new manuscript was safe, it seemed, from some enterprising con artist who wanted them for… well, to read them, it seemed. Filippo Bernardini was unmasked last year and his case came to an end in March when a judge convicted him of a felony, without jail time. The judge described the case better than anyone: “I have no idea what to do with this case, and I’ve thought about it a lot. I don’t expect to see anything like this ever again.” The guy just… wanted to read books in advance! And instead of asking for galleys like the rest of us, he engaged in a moderate amount of fraud. We at Lit Hub are not endorsing any further breaking of the law, but it’s also true that this year was a little more boring without a great unifying mystery like this one to bring us all closer together. –DB

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.