Teju Cole on the Wonder of Epiphanic Writing

Or: How Authors “Evoke the Overspilling World”

The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”

“The Dead” begins at an annual Christmas gathering for friends and family in Dublin early in the 20th century. After the party, we are with a couple, the Conroys, heading to their hotel. And then we are with just the troubled thoughts of Gabriel Conroy, who is ruminating on what his wife Gretta has just told him about something in her deep past: when she was a girl, she loved a boy and the boy loved her. This boy, Michael Furey, waiting outside her window all those years ago like a figure in myth, or like a figure in a faintly remembered dream, later caught some illness and died. A song she heard at the party earlier that night had brought all this back to her. And now she is asleep in the hotel room and her husband, Gabriel, is awake, with his blizzard of emotions. Having zoomed in on the smallness of Gabriel Conroy’s concerns, of his angst at not having known the long-guarded secrets of his wife’s heart, Joyce zooms out again, taking in the entire landscape, deploying chiasmus and alliteration: “His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

It is as classic as a 20th-century literary passage gets. In my novel Open City, a book that is about many things, but certainly about how one man’s life is invaded by literature and literary antecedents, I cited “The Dead” directly. My narrator, Julius, is in Brussels, looking for his grandmother. He has spent most of his time wandering around in a haze of depression. To him, Belgian history and current Belgian politics both feel like open wounds, but there are personal pains he’s intent on suppressing too. But he’s also had a series of random encounters in the city that now come back to him. His journey is coming to an end. In one paragraph, I substitute rain for snow, and Belgium for Ireland, but otherwise make few changes to Joyce’s original. The lifting is obvious and unsubtle. Mature poets, as Eliot had it, steal (it is obviously another matter if your intention is to never be found out). My literary interests have been shaped in part by modernism, by Joyce and Woolf, by Mann, Musil, Broch: the flow of thoughts through minds, the blending of sensation into lyric passages. Far from having any anxiety of influence, I am skeptical of an originality that does not place itself in conversation with antecedents.

The ending of “The Dead” showed up again in a later book of mine, Blind Spot. The passage, titled “Rivaz,” is an account of a walk, and it is the penultimate entry in the book. It is a hymn of gratitude, full of sunshine, not nocturnal, far from rain and snow, the Joycean rush of it becoming apparent only at the very end, when I write “No longer are we alone: they are with us now, have been all along, all our living and all our dead.”

What we think of as the Joycean epiphany has strong 19th-century models—in Emerson, in Wordsworth—and it has had a vigorous afterlife in 20th-century fiction. Perhaps too vigorous, if you are Charles Baxter, author of “Against Epiphanies.” Baxter sees too many pat epiphanies, too many neat flashes of insight and pithy summations in contemporary American fiction, particularly in short stories. The lyric moment happens, and the conundrum the character has been mulling is suddenly solved. It’s all too easy. I think Baxter’s right, and I take advantage of the flexibility of the term epiphany to think not about this particular narrow narrative device, but rather of a stylistic mode which, as often as not, puts us in place but neither advances the plot nor solves any problem.

The secret reason I read, the only reason I read, is precisely for those moments in which the story being told is deeply and almost mystically alert to the world.

This passage from Mrs. Dalloway, for instance, does not really bring some staggering moment of insight. What it does is cook a list, nourish the eye and the ear, and bring us closer to Clarissa’s consciousness and to ours:

For Heaven only knows why one loves it so, how one sees it so, making it up, building it around one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh; but the veriest frumps, the most dejected of miseries sitting on doorsteps (drink their downfall) do the same; can’t be dealt with, she felt positive, by Acts of Parliament for that very reason: they love life. In people’s eyes, in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment in June.

Reading Woolf, we are with her: creating every moment afresh, awakened further with each semicolon. A different master of this mode is W. G. Sebald, who, of the writers I have studied, might be the one in whom this intense, emotionally charged but intellectually unflagging approach is most pervasive. Sebald wrote entire books that are almost nothing but the headiness of an associative dream. The Rings of Saturn is a narrative of a fictional walk in Suffolk, the journal of a man who seems to carry around an antiquarian hypertext library in his head. I’m especially taken with the skill with which Sebald, at book length, connects one thought to another. If you stare hard, you can see the stitching—he’ll say “it occurs to me that,” or that so-so “may well have had an eye for these things”—but you only see it if you’re searching. Otherwise, what you have is a highly controlled delivery, a billowing cloud seen in slow motion.

I still remember my shock when I read The Rings of Saturn for the first time, a shock of illumination that was also a shock of recognition. The literary attitude I’m describing is characterized by a certain density, whether it is dealing with a dark and melancholy interiority, as in Sebald, or with the thrum and possibility of city life, as in Woolf, Walter Benjamin, or Bruno Schulz. Cities are made of multiplicity, and they invite inventory. To list is, somehow, to love. The following is from Toni Morrison’s Jazz, a book whose acceleration, attack, and improvisatory slyness honor the music of its title:

Breathing hurts in weather that cold, but whatever the problems of being winterbound in the City they put up with them because it is worth anything to be on Lenox Avenue safe from fays and the things they think up; where the sidewalks, snow-covered or not, are wider than the main roads of the towns where they were born and perfectly ordinary people can stand at the stop, get on the streetcar, give the man the nickel, and ride anywhere you please, although you don’t please to go many places because everything you want is right where you are: the church, the store, the party, the women, the men, the postbox (but no high schools), the furniture store, street newspaper vendors, the bootleg houses (but no banks), the beauty parlors, the barbershops, the juke joints, the ice wagons, the rag collectors, the pool halls, the open food markets, the number runner, and every club, organization, group, order, union, society, brotherhood, sisterhood or association imaginable.

“Everything you want is right where you are,” she writes. The scene is like that concept of the novel Stendhal wrote of in The Red and the Black: “A mirror carried along a high road.” We find a similar inventorial approach in Orhan Pamuk’s Istanbul. The subject of this passage is hüzün, the melancholia specific to Istanbul and Turkish history itself, which Pamuk begins with innocuously enough with the phrase “I am speaking of the evenings when the sun sets early,” but which he then takes very far indeed. The passage runs on, as a single sentence, for several pages, coming to more than a hundred lines, and ending as follows:

. . . of every thing being broken, worn out, past its prime; of the storks flying south from the Balkans and northern and western Europe as autumn nears, gazing down over the entire city as they waft over the Bosphorus and the islands of the Sea of Marmara; of the crowds of men smoking cigarettes after the national soccer matches, which during my childhood never failed to end in abject defeat: I speak of them all.

Each prepositional phrase is set off with the device “of the” such and such—like a chain of biblical “begats”—and each recalls the opening “I am speaking of”: of the evenings, of the fathers, of the old Bosphorus ferries, of the storks flying south. The repetition invites a hypnosis over the length of this gargantuan passage, and the technique is evocative of the fog of melancholy that the passage itself is describing, a hypnosis like that triggered by “falling”—the repeated word itself trochaic, falling—in Joyce’s “The Dead.”

And one cannot help but imagine, in this kind of inventory, an authorial and narrative self guiding us through the experience of city life, through its crowds and personages and ever shifting sights. At times it’s as though such authors are obeying Isherwood’s dictum: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.”

Those moments that are like a dark forest, a wide sky, or a landscape full of human history.

In literature, the camera is metaphorical; in film, it is literal. Cabiria, the lovelorn sex worker who is the hero of Fellini’s 1957 film Nights of Cabiria, is certainly not Federico Fellini. The role is played to perfection by Giulietta Masina. And yet, at certain heightened moments, what we experience is a merging of her vision with his, and that vision becomes ours as well. In the final scene of Nights of Cabiria, Cabiria, disappointed in love yet again, wanders from the edge of a desolate lake into the quiet woods. She’s all alone, she’s been crying and now wears a stony expression. Music begins to play, she walks past trees and is now on a road. First one woman enters the scene, then another, lively, calling out, then several characters in the distance, prancing, playing music. Guitars, party hats, a motorcycle, an accordion, all become visible onscreen. The screen fills up with youthful revelers. Cabiria continues walking down the road, but the night’s temper has changed. The music gets louder, the revelers try to draw her into their revelry. “Buona sera,” one sweet-voiced girl says, and poor sad-faced Cabiria, with the makeup of a circus clown, softly smiles. The music builds to a crescendo and she’s smiling more broadly now, through tears.

8½, made later, is a film about making a film. The conclusion to 8½ is like a perfected form of the idea Fellini had first attempted six years earlier in Nights of Cabiria. It is a longer scene, it is more complicated, but the same energy pertains: that of an individual swept up in the sights and sounds and personae of others all around, all that activity rising to a crescendo, a sensational crescendo, because all the senses are being excited. We see things, we hear the voices and the music, and we imagine all the things the characters must be feeling. Guido, the lead, played by Marcello Mastroianni, is experiencing all the complexities of his life as a dream sequence in the form of a grand parade—his long-dead parents, his colleagues, his lovers, everyone is magically there— with himself as the band leader.

Fellini’s filmmaking, Nino Rota’s music, infectious joy. More sober is James Salter in his memoir Burning the Days. This passage from Salter is one to which I say, yes, this, too, is where I want to be. We are brought across the landscape by a solitary figure on whom all of it, out there, is having an effect, who is receiving all of it with senses tuned. It is morning, but light is still low. If it had music, it would be an andante, the music of flight and morning:

Below, the earth has shed its darkness. There is the silver of countless lakes and streams. The greatest things to be seen, the ancients wrote, are sun, stars, water, and clouds. Here among them, of what is one thinking? I cannot remember but probably of nothing, of flying itself, the imperishability of it, the brilliance. You do not think about the fish in the great winding river, thin as string, miles below, or the frogs in the glinting ponds, or they of you; they know little of you, though once, just after takeoff, I saw the shadow of my plane skimming the dry grass like the wings of god and passing over, frozen by the noise, a hare two hundred feet below. That lone hare, I, the morning sun, and all that lay beyond it were for an instant joined, like an eclipse.

I am dazzled and helped by passages of this kind. Conversations between characters are all well and good; I suppose countesses must sweep into rooms, as they do in certain novels. But the secret reason I read, the only reason I read, is precisely for those moments in which the story being told is deeply and almost mystically alert to the world, an alertness that sees things as they are or dreams them as they could be. Those moments that are like a dark forest, a wide sky, or a landscape full of human history.

In Open City, after Julius receives news of a death, he is induced to walk a great distance, all the way from Harlem to Chinatown. I gave an account of this walk in a long and complex passage that extended over several pages. Those pages, perhaps the strangest in the whole novel, were an attempt at a certain kind of epiphanic writing. In writing them, I was thinking about the many wonderful instances in which the density of a text, or the artfulness of a camera’s movement, had been used to evoke the overspilling world. I wanted to pay homage to that kind of inventory: of what could be felt or seen but never fully described.

__________________________________

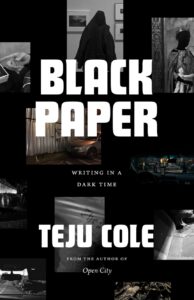

Reprinted with permission from Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time by Teju Cole, published by the University of Chicago Press. (c) 2021 by Teju Cole. All rights reserved.

Teju Cole

Teju Cole is a novelist, photographer, critic, curator, and the author of seven books, which include Open City, Blind Spot, and Golden Apple of the Sun. He was the photography critic of the New York Times Magazine from 2015 until 2019. A 2018 Guggenheim Fellow, he is currently the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard.