Earlier this year, Edward St. Aubyn spoke with Merlin Sheldrake about their most recent books: St. Aubyn’s Double Blind, which wrestles deeply with ideas and questions from the sciences, and Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, about fungi. Their conversation is below, and you can listen to them together on Vintage Books’ podcast here.

*

Merlin Sheldrake: I’m interested in what led you to write this amazing novel, Double Blind. What caused you to think and write about the sciences and the practices of the sciences?

Edward St. Aubyn: Well, I think the trouble probably started as long ago as 1996, when I went to a conference in Tucson, Arizona, called Towards a Science of Consciousness, and realized that consciousness, which is the only thing we know we have and the basis of everything else we think we know, was something which hadn’t been successfully included in science’s majestic description of the world. And as time went on, I started to wonder to what extent the authority of science was undermined by that explanatory gap. The first-person narrative of experience seemed to refuse to be reduced to the third-person narrative of experiment. And the narrative of electrochemical activity and neuroimaging and genetic sequences somehow failed to capture the quality of being alive.

This book took me a long time to write because I wasn’t trained as a scientist. My subject at university was English literature. I had to try and absorb so much new and alien knowledge and then integrate it into a fictional world of characters and plot and imagination and metaphor.

What struck me about Entangled Life was how much you integrated imagination and metaphor into a book written about a scientific subject. Was that something you thought about a lot while you were writing it?

MS: Yes, it was. One of the reasons that metaphor plays an important part in scientific inquiry is because researchers often explore phenomena which are inaccessible to their unaided senses. Metaphors and analogies provide frameworks that guide our imaginations and help generate new ways of thinking. Metaphors and analogies, in turn, come laced with human stories and values, meaning that no discussion of scientific ideas—this one included—can be free of cultural bias.

In particular, I wanted to explore the metaphors that have been used to make sense of the subvisible world of microbes and try and think about new ways to imagine these phenomena. It seems to me that we need a balanced narrative diet. We get into trouble where we prioritize one type of story over other types of story for ideological reasons.

ESA: Even the title of the first chapter of Entangled Life, “What is it like to be a fungus?” is surprising. I took it to be an echo, to some extent, of Thomas Nagle’s famous essay on what it’s like to be a bat. There are other worlds of experience that we only have limited access to because we have different bodies, but we can explore them through imagination. I was struck by how much you made an effort to see the world from the fungal point of view, in the same way that I try and make an effort to imagine other mentalities and characters who have lives completely different from my own. Did you throw yourself into that process very consciously?

MS: Yes. When thinking about the living world I feel like I have a responsibility to try to step outside my human-centered perspective. Even if my attempts to see the world from a fungal perspective are doomed to failure I feel that it’s good manners to try. We won’t be able to understand fungal lives unless we at least make an effort to think about the worlds that they’re exposed to from their point of view.

ESA: In a sense, metaphors resemble one of the great themes of your book, which is not only about this relatively obscure kingdom of life—fungi—but about symbiosis, in that metaphor takes elements from different parts of experience and brings them together. If a ship ploughs through the water, the agricultural and the nautical are brought together and generate a hybrid in our imagination—in that case a very clichéd one, but a cliché is just a metaphor that’s been destroyed by its own success.

Symbiosis is something that was a revelation for me in reading Entangled Life. The complexity of these relationships is astonishing. Not only do fungi collaborate with plants, but within the fungi are bacteria, and sometimes bacteria within bacteria. Your descriptions totally justify the title of the book. Were you aware of this before you started your fieldwork, or was there a process of discovering life to be more and more entangled as you went along?

MS: The more you look, the more entangled the living world becomes, which is a great thrill. When I was doing fieldwork in Panama it really hit home, because I existed there in a kind of disciplinary symbiosis. In chatting with other researchers I would find out that they were thinking about an aspect of my subject matter but from the perspective of another other actor in that relationship.

Historically, professional specialization within the sciences made it difficult for researchers to study the relationships between very different organisms because they were separated by disciplinary chasms. One of the trends that we’re seeing now in the biological sciences is towards more and more interdisciplinary work. And I think this is a reflection of our greater understanding of the living world as inextricably entangled; fundamentally so.

Something I really enjoyed about Double Blind is that many of the characters are wrestling with different kinds of scientific problem, but that as a reader, I experienced the scientific problem and inquiry firmly embedded within their lives. Their own personal, emotional, and intuitive worlds are in dialogue with their scientific inquiries. Scientists are not portrayed as disembodied rationalities. Your approach helps to explore the role that disciplinary relationships can have in our lives, and how confusing it is when we start trying to divide one area of human thought and experience from another.

ESA: Well, I felt that was my responsibility as a novelist. Although I was fascinated by scientific arguments and interpretations, I couldn’t turn my characters into advocates of one position or another. Unlike the novelist Thomas Love Peacock, who created characters like the phrenologist, Mr. Cranium, I resisted the temptation of having a neuroscientist called Mrs. Magnetic-Resonance.

I wanted my characters to be rounded human beings. W. H. Auden said that he was a poet when he was writing poetry and the rest of the time he was a person. And I felt that this must be true of scientists as well, that they didn’t wear their white coats in bed. I also wanted to ground science in ordinary human experience. There’s a character in my novel who’s suffering from cancer. There’s another character who’s schizophrenic. These are ways into science that don’t go through the laboratory door. We’re all living with science the whole time: during this pandemic, for example, or when we wonder what to eat, or how to travel.

MS: One of the things that becomes clear when you think about the sciences is that they are not unified and monolithic, but rather an evolving collection of practices and values undertaken by people with very different backgrounds and ways of thinking and understanding. A quantum physicist is a layperson with regard to a herpetologist, for instance. There’s a wonderful passage in Double Blind where you discuss this.

The character, Saul, says: “I guess the thing I’ve been trying to get across to you over the last year is that if science offered a unified vision of the world, it would be a pyramid, with consciousness at the apex, arising explicably from biology, and life arising smoothly from chemistry, and the Periodic Table, in all its variety, emerging inevitably from the fundamental forces and structures described by physics; but in reality, even physics isn’t unified, let alone unified with the rest of science. It’s not a pyramid; it’s an archipelago—scattered islands of knowledge, with bridges running between some of them, but with others relatively isolated from the rest.”

I wonder if you could talk a little bit about this image and how this became a theme for you.

ESA: I felt that there were puzzling explanatory gaps between the big branches of science, and that what Saul just described is true: there isn’t a pyramid, although we’re often invited to believe that we’re only minutes away from seeing it completed. The way forward is going to be in integrating different disciplines, in going with the bridge builders and not the wall builders—a familiar situation—and in finding ways to collaborate. This rests on an assumption that there’s a unity to knowledge, that we can approach describing reality together, whether it’s from the point of view of a fiction writer or a field researcher.

There’s an enjoyable passage in Entangled Life where you take LSD under very controlled conditions. Being a scientist, you don’t take psychedelics in a hedonistic or haphazard way, I’m pleased to say. It was administered by a nurse who made sure that you swallowed the entire dose in the beaker. And after your experience, you had to fill out a psychometric questionnaire, and you write this:

“The psychometric questionnaire I was struggling to complete had been designed to assess this kind of experience. But the more I tried to cram my sensations into a five-point scale on a page, the more confused I became. How can one measure the experience of timelessness? How can one measure the experience of unity with an ultimate reality? These are qualities, not quantities. Yet, science deals in quantities. I squirmed, took several deep breaths and tried to approach the questions from a different angle. How do you rate your experience of amazement? The bed seemed to sway gently and a school of thoughts scattered through my mind like startled minnows. How do you rate your experience of infinity? I could feel the scientific procedure groaning under the strain of what seemed to be an impossible task.”

I love this passage because you’re taking psychedelics, which are category-dissolving and ego-dissolving, and which throw the whole subject/object relationship into question. And then, because of the habits of science, you have to award points to these various kinds of transformative experience. On the one hand, you have the quantitative habit of science and on the other hand, the qualitative nature of experience. What did you end up writing on the questionnaire, or did you abandon it?

MS: Well, I spent much of the time laughing but I couldn’t abandon the questionnaire. I had to fill it out every hour or so; there was no escape.

ESA: Oh, I didn’t realize! I thought it was a one-off.

MS: It was a remarkable situation. The nurses would come in and take a blood sample from my arm, and immediately afterwards I would contend with the questionnaire. The blood samples provided the investigators a way to observe my body, as matter. The questionnaires were designed to give them access to my subjective, qualitative experience—as if objectively. The whole dance of the experimental procedure became unbearably funny.

We’re all living with science the whole time.

It’s often taken for granted among scientific researchers that we can subject more or less anything to an experiment as long as we’re deft and intelligent enough to design a suitable course of study. But there are some things that you just can’t access in an objective fashion—like the inside of someone’s subjective experience. I feel like this pantomime gets to the heart of the matter that you described earlier—the relationship between first-person experience and third-person experiment.

ESA: Absolutely. It’s no wonder you were laughing. You were undergoing an experience which threw into question the whole idea of objectivity because often under the influence of psychedelics, your subjectivity flows into an object and the object flows into you, and can make the strain of clinging to the old divisions between subject and object seem absurd.

Do you feel that fungi have a special genius for taking over animal minds? There’s a vivid passage in your book where you describe the startling example of carpenter ants which become possessed by a species of Ophiocordyceps. What I found particularly interesting about your description was that the fungus doesn’t grow into the ant’s brain. We would assume that the first thing one would try and get control of would be the brain because we have a central nervous system. But the fungus doesn’t have a brain and it doesn’t go for the ant’s brain. It commandeers the ant by other means.

MS: Yes. The researchers who reported the phenomenon were surprised to find out that the fungus was everywhere in the ants; as much as 40 percent of the mass of an infected ant is fungus. But one of the few places the fungus wasn’t were the ants’ brains. This led them to suggest that the fungus is able to puppet ants’ behavior by releasing chemicals that act on the brain, controlling the behavior of their hosts with exquisite pharmacological precision.

The fungus causes ants to climb up to a particular height—25 centimeters above the forest floor—and to bite onto the underside of leaves. The fungus orients ants according to the direction of the sun, and infected ants bite in synchrony, around noon. They don’t bite any old spot on the leaf’s underside. 98 percent of the time, the ants clamp onto a major vein. One of the researchers, David Hughes, describes infected ants as a fungus in ants’ clothing. By hijacking an animal body the fungus gets the benefits of animalhood for a short while and then it can return to its decentralized fungal ways.

ESA: On the symbiotic spectrum, that sounds like a clear case of parasitism. On the other hand, you point out in Entangled Life that historically there was resistance to the idea of truly mutual relationships. One of the metaphors you objected in the case of lichen, for instance—a symbiosis between fungi and algae that forms a new fusion—was that of master and slave. Seeing through the assumption that one of the participants is always in charge at the expense of the other was an important breakthrough, wasn’t it?

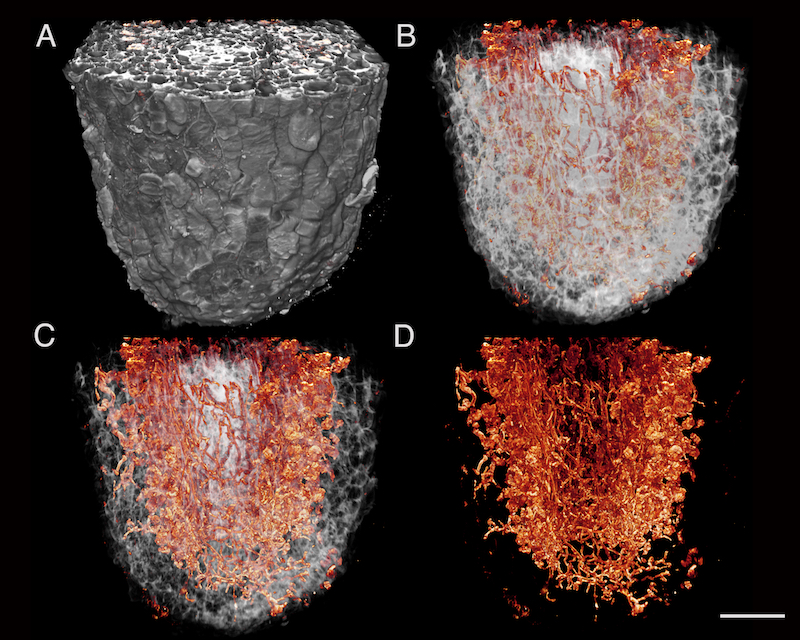

MS: Definitely. When you think about fungi for more than a minute or so it becomes clear that you can’t talk about these organisms without talking about where they’re living and with whom they’re entangled. Mushrooms are only the fruiting bodies of fungi: for the most part, they live their lives as branching, fusing networks of tubular cells known as mycelium. Mycelium is how fungi feed. They insinuate their bodies within sources of food and then digest it. This means that they need maximum contact with their surroundings, which makes it very hard to think about what a fungus is doing without also thinking about where it happens to be. I’m reminded of that John Muir line, that when you try to pick out anything by itself, you find it hitched to everything else.

In Entangled Life, I think a lot about the shimmering networks of interconnectivity and interdependence from which we’re inseparable and in which we belong. Individuals aren’t so much natural facts as categories that depend on our point of view. The intricacy of these webs of relation raises interesting questions for researchers studying the living world. What are you calling an individual?

For the purpose of this study, how does it make sense to define an individual? You have to enclose and define your subject matter somehow, otherwise systematic investigation would be overwhelming. And so the question of where you draw the line becomes a question rather than an answer known in advance.

ESA: Absolutely. We need to pretend to be an individual when we’re applying for a passport or paying a parking fine, but we’re unlikely to end up thinking that it’s a fundamental idea if we’re lucky enough to be invited to a hospital to take LSD. Or indeed, if we think about resting in awareness, as one of my characters—a naturalist called Francis—does while he’s walking around a rewilding project that he’s helping to run. And by resting in awareness he’s trying to get to something beyond his individuality, beyond the accident of his personality. Many of the most interesting experiences involve seeing through individuality to a deeper interdependence, something you’ve studied in great detail biologically, but which has been discussed in many forms, from many different points of view.

Individuals aren’t so much natural facts as categories that depend on our point of view.

MS: While reading Double Blind I enjoyed spending time within long, blossoming thoughts that unfurled over whole chapters. I had a strong sense that the conscious experiences that are being relayed had a branched, connective structure, rather like a shrub or a fungal network. They felt like portrayals of minds as a living organisms; flows of consciousness constantly growing into new spaces and into new relations. I feel that there’s a connection between the inquiry into the way that we think—the way that we experience our minds from the inside—and the ways that organic forms arise in the living world; in what we can see a fungal network or a plant’s root system doing, for example.

ESA: If consciousness doesn’t emerge as a complete surprise out of this dead world, one of the reasons might be because everything is proto-conscious; that our particular form of consciousness is just one way in which these proto-conscious elements are arranged; that creatures without brains and without central nervous systems, like the slime molds you write about it so enchantingly, can also be having some experience or at least exhibiting intelligence.

There are countless ways to be alive. Even atoms are full of fervent activity, with electrons spinning around nuclei. They’re not as dead as we like to think when we put ourselves into an I/it relationship to the world, which is what reinforces our sense of isolated individuality. This is one of the reasons I think Entangled Life is in such interesting territory because by questioning these borders, we’re opening up the possibility of solutions to some of the chronic problems which generate dualism, fragmentation, over-specialization, and misery.

MS: There’s a passage that I’d like to read from Double Blind on the subject of Darwin. This is Francis reflecting: “Being a naturalist wasn’t a bad tradition. After all, before Neo Darwinism, there’d been Darwinism. And before Darwinism, Darwin, a man writing about earthworms, and making detailed observations of living creatures, and joining pigeon fancying clubs, and gardening, and corresponding with other naturalists without treating their testimony as merely anecdotal.”

ESA: The anecdote is precisely where experience can turn into evidence, and not just under the extremely controlled conditions of a double-blind experiment. We don’t have to shoo away anecdote, as if it was a stray dog that was going to invade our perfectly sterile picnic.

MS: Some people say the plural of anecdote is data, but many within the sciences say that this is not the case, because what we think of as datum is not just incidental information received in the normal course of a day, as an anecdote might be. Rather, data has been teased out of the world through a careful arrangement of apparatus, procedure, and replication that we might call an experiment. But it’s not always possible to perform controlled experiments. Much of astronomy, for example, depends on what phenomena researchers are lucky enough to observe. We can’t start intervening experimentally on a cosmic scale in the way that we would do in a controlled and replicated study down here on Earth. Pulsars or fast radio bursts just happen. They’re celestial anecdotes, in a sense.

Anecdotes can also become part of scientific explanation, as you discuss in Double Blind so elegantly. Many of the stories which are used to make sense of the nature of reality become anecdotal in their retelling and retelling and retelling, sometimes to the point where we forget that really what we’re saying is we don’t know how or why something is the way it is.

ESA: In a sense, the Big Bang is an anecdote, and it begins with a tautology: initial conditions. What else could there have been but initial conditions at the beginning? We still have a mystery, an unsolved mystery at inception. I think Terence McKenna used to say, “Give me one free miracle and I’ll explain the rest.”

MS: The free miracle being the creation of matter and energy and all the laws that govern it in a single instant, from nothing.

When you answer a question, it stops being a question.

ESA: Exactly. So once you grant me that, which we’re going to fig leaf with the phrase “initial conditions,” then everything makes perfect sense. But I prefer to experience the vertigo of what we don’t know.

MS: I agree. There’s a perhaps more old-fashioned form of science communication which involves disseminating slick certainties to a naive public who need to be filled with facts. I find that I learn much more if I’m invited into the big questions and shown how to navigate the uncertainty, even though it’s not always easy to be comfortable in the space created by open questions. Agoraphobia can set in. It’s tempting to hide in small rooms built from quick answers. But when you answer a question, it stops being a question. In some sense, you’ve killed the question with the answer. An open question that you’re not in a hurry to extinguish, in contrast, summons you into its continued becoming.

ESA: I think that’s what makes life and narrative dynamic and entertaining and honest.

__________________________________

Double Blind is available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Edward St. Aubyn.