Surviving New Orleans: On Love, Death, and Life in a Hurricane

Anne Gisleson in Conversation with C. Morgan Babst

Fifteen years ago, Anne Gisleson stood in front of a chalkboard at the top of a crumbling public school building and taught me how to read and write fiction. The windows of our writing classroom at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts looked out over the rooftops of the city, a blue-sky view that stretched all the way to the canopy of live oaks that arches over Audubon Park. Inside the classroom, Anne—together with many other generous New Orleans writers—took us, a rag-tag bunch of teenaged book nerds, through as much of world literature and film as could be crammed into three years of three-hour days. Through Welty and Genet, Thomas and Lorde, Murnau and Marker, we studied our craft with an intensity and focus unsurpassed by any of my classes at Yale or NYU. I’d do it all again now, if they’d let me. But since then, NOCCA has moved to sturdier digs downriver, New Orleans was flooded in the levee failures following Katrina, and Anne and I have gotten far enough away from that classroom to have a drink together—bourbon rocks for her, rye Manhattan for me. Recently, we sat across a little table together and talked about the storms, deaths, and reading binges we’ve survived since we last saw each other—and the books we made of them.

–C. Morgan Babst

CMB: I finished reading The Futilitarians last weekend, lying in slatted shutter light while Hurricane Nate staggered away from the mouth of the river. It was an eerie moment of reading: a plunge back through the last decade and a half, a stretch of time that syncs strangely with our last conversation about writing—at NOCCA—and today’s. It’s been a dark period, one that I’ve thought of as a kind of post-Katrina katabasis and that you’ve written about as a journey through a dark wood. This feels too tender to type about, but I am so very sorry for your losses.

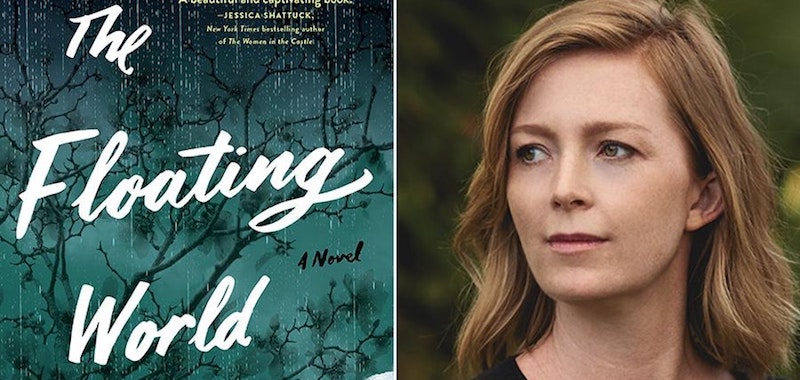

Anne Gisleson: Thanks, Morgan. I opened the envelope with The Floating World on the afternoon that forecasts for Hurricane Nate were laying a line straight through Orleans Parish. I saw that glorious, stormy cover and thought, “Oh, no no no.” But even though I had a visceral reaction to holding your book while a hurricane was menacing the Gulf, I read the first chapter, standing by the mailbox, riveted.

Funny you bring up katabasis, this idea of the journey to the underworld, towards the dead. Both our books begin prominently at night, invoking the dead in these otherworldly water-haunted landscapes. Mine even has an image of Cerberus guarding Hades. I hadn’t thought about that until you brought it up.

CMB: I knew from your first page, when, on your “Nighttime Industrial Jungle Cruise” you drink cocktails called “Night of Deepening Memory,” that we were prowling the same territory.

I became weirdly obsessed with the underworld after Katrina. In those weeks of flood, we had been literally separated from our lives by a dark, reeking lake, and it seemed likely that we would never be allowed to return to the other shore. I was worried about how much we would forget—and whether it would be possible to rebuild this city that sometimes seems to function solely out of habit, when so many of its memories had been washed away. My very rational response to these fears was to read the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and Virgil, and Dante, and books and books and books on mystery cults. It probably would have been good for my sanity if I’d tried to get other people to read with me, but I doubt I could have drummed up much interest in a Stygian Crisis Reading Group.

I’m interested to hear that you didn’t intentionally load your book with the katabasis that—probably due to my personal fixations—I found all over it, from your discussion of Koestler’s “Night Journey” archetype to your trips to Angola where you find shades of your father in the visitation room with his former client. I found myself thinking a lot about Aeneas while I read The Futilitarians. When he goes to Hades, it’s not to drag anybody back up to the daylight again but to check up on Dido and hang out with his dad. Your voyage, like that one, seemed to be about reaching to the dead for understanding, for communion. About achieving a sufficiently strong grip on the past that you can carry it forward into the future.

AG: Considering my father’s threat that if I ever wrote about my sisters’ suicides, he would take his anger over it to his grave, writing the memoir did feel like reaching out to him in his underworld of murky, conflicted motivations. I was also obviously trying to understand my sisters, who I was really writing about for the first time. While I was working on The Futilitarians I had a picture of them on my laptop’s desktop. So young and beautiful, in these strappy evening gowns, all this luminous skin. Every time I opened my laptop, there they were, Rebecca looking directly at me with a kind of smirk, Rachel looking at Rebecca. I knew I’d arrived on the other shore when after the second or third draft of the book, I no longer felt unsettled looking at that photo; instead, I felt a weird sort of peace, and I was able to drag it back to a neat little folder.

CMB: That movement, from discomfort to peace, is palpable in your book. And, for a memoir as haunted by death as yours is, your launch party at the Saturn Bar was one of the most life-affirming book events that has probably ever taken place. As far as I could tell, all of literary New Orleans was there, and I spent most of the night hemmed in by poets in a continuous circuit of the bar-line, alternating between pressing a frosty Red Stripe to my temple and dabbing my friend’s spearmint oil on the insides of my elbows. I’d worked up a real good New Orleans summer bar sweat by the time I made it to the front of the signing line. My mascara was running—your mascara was running—and it felt so good to hug you, to have you sign your book for me after 15 years out of touch. Still, I could feel that hole tragedy had carved out of our lives like a physical cliff behind us. Don’t fall, I thought (though maybe that was just all the Red Stripes).

AG: I didn’t know my mascara was running! But yes, that launch party was intense. The Futilitarians feels so much like a product of the communal—of growing up in a big family, of New Orleans, of our Existential Crisis Reading Group —that it seemed appropriate to have a big, messy, exhilarating event. Also, the Saturn Bar’s chief charms are of accumulation, of time, booze, art, ephemera, loss, celebration. When you invest most of your life in one place, in our case New Orleans, you’re rewarded by wonderful moments like when I got to sign your book and give you a sweaty hug. So much shared, lived history between us. But that night it was almost too much.

On every page of the The Floating World I feel the accumulation of the material and metaphysical and emotional weight that comes from knowing a place so well. Did that ever become overwhelming for you? How did you sort it all that out?

CMB: I think maybe, if you’re from New Orleans, it’s always overwhelming; most of the time, we’re up to our necks, and then sometimes the water rises. I’m amphibious, though, I guess—other places, the air’s too dry to breathe, and my skin cracks in less than 98 percent humidity. I did do a good little bit of running away, however. I remember a particular moment the summer I was twenty, sitting on a barge in the Fontanka Canal in St. Petersburg with this brilliant budding linguist and a crazy Swedish woman I’d met in Russian class, and thinking: “Nobody here knows my mom!” I looked down at Katya’s combat boots, then inched my hand across the table to steal one of Johanna’s Pyotr Perviis, the official cigarette of the Russian navy. While I sat there hacking up a lung, I felt, for the first time, actually free. It’s a sentiment I gave to Del in The Floating World—that only away from New Orleans is it possible to self-define—but I also gave her my unhealthy dependency on this city.

AG: You know, I’m envious of your loving generosity towards the city; you write about it with so much affection and insight. I grew up in state of ambivalence towards the place, my mother many generations in and my father an outsider. For over 40 years, he harbored that particular Midwestern love for New Orleans, its wildness and freedoms. He raised eight kids here, but even so, he always said he couldn’t claim to be “from” the city. Our mom embraced local ritual but also created her own, encouraging us to live in a way that’s most meaningful to us and not merely inherited. I think all that kept me from firmly anchoring myself anywhere within the many cultures of New Orleans and also open to all of them. While New Orleanians can fall into generational ruts, the city at its best can teach you to be flexible across many cultural lines and create the home you want.

CMB: Yeah, the city’s multiplicity is its best quality—that it can be for everyone, and sometimes all at once. Of course, we often also impede, neglect, and harm each other in ways that are literally deadly, as we did in 2005. I love the city, yes, but it does infuriate me that, while we throw the finest parties on earth, we can’t seem to take care of each other when it matters. With the completion of my novel, though, I feel like maybe I can put the anger away and start moving beyond all that destruction towards more fertile territory. Do you feel this too?

AG: Oh yeah. It definitely feels as though I’ve left that land and arrived in another terrain, one with its own joys and difficulties. And I’ll probably always be angry at New Orleans for something.

Both of our books end at night, just as they began, but it is a night of a different quality, affectionate and filled with connection and fellowship. Everyone’s still in darkness, but they’re together, they’re celebrating, and that’s okay.

CMB: I wonder if writing your book—which works, like the best memoir does, as a chronicle not so much of events but of mind—helped you carry your grief forward? I’ve always thought of the compulsion to repeat and relive crisis as a pathological symptom of grief—one I suffer from—but you made me think about it in a new and really helpful way.

AG: Well, is it repeating and reliving, or is processing and remembering? As Kierkegaard said, “Repetition is the same movement as memory, but going the other way… repetition is memory carried forward.” But every step forward is filtered through the time that’s passed, so memory is constantly being transformed. But in The Floating World, time doesn’t move forward in an orderly way—it seeps and swirls.

CMB: Yeah, it used to seep and swirl so much that I got in trouble with my editor. . . Through a few failed structural experiments—and the more successful ones that remain—I was trying to enact the way trauma disorders narrative. We tend to think of our lives as being strictly linear, though they’re not. We expect to move forward every day—changing, growing, learning—but grief and crisis are like low pressure systems, they suck us into them with tremendous force, even as we try to move away.

In these last 12 years, I’ve often thought about the afternoon my brother and I spent on the levee as Hurricane Georges made landfall 90 miles to the east. We spent the better part of an hour standing at the brink of the shell path, looking out over the river, leaning on the wind. It was so strong that we couldn’t move forward, couldn’t fall. Years later, it was on that levee that a good friend of my brother’s shot himself, done in by depression after the storm. Writing the novel was, in part, my attempt to understand how a disaster can stop a person’s forward momentum—how, even in the aftermath, the past retains its force. Caught in Katrina’s convection, I wanted to figure out if it would ever be possible to get away.

On the anniversary of Katrina this year, the mayor gave most of New Orleans the day off; he called it a “flash flood warning,” but it didn’t rain much. Instead, as far as I know, we all sat in front of our televisions watching Harvey fill Houston with water, reliving a 12-year-old storm. Everyone I know spent that day feeling awful, and we all got drunk that night, and most of us sent money and clothes to Houston, who’d taken care of us when we’d needed it. Afterwards, I felt maybe a little bit lighter; or, if not lighter, then at least less jittery, more whole, if that makes sense.

When you quoted Koestler, who writes about “establish[ing] contact with the Tragic Plane,” I thought—yes, that’s what this repetition is. A way of keeping the lines of communication open with our past selves, trying to incorporate our tragedies into our lives—so that they’re less like holes than mile markers.

AG: I like that—“keeping lines of communication open with our past selves.” And also open to other people who’ve suffered and are still suffering. There’s such an obsession with “resilience” these days, the go-to word after our increasingly frequent large-scale disasters, both natural and man-made. It’s used with such alacrity and approval in the news cycles, that it can remove the burden from everyone else to act or even feel. I worry that it shuts out the real value in fully connecting with tragedy, and I hope that we can come to a new understanding of how we really deal with disasters, that allows people to suffer and assess and recover at their own pace, and in their own way.