Secret, Unruly, and Progressive: The History of the Heterodoxy Women’s Club

Joanna Scutts on the Early Days of the Feminist Social Club in Early 1900s New York

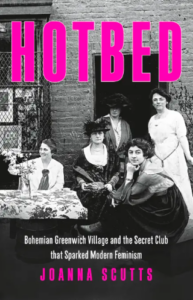

Header image via Impossible Objects.

On Saturday afternoon, in a place that feels, just then, like the brightly pulsing center of the universe, a group of women gathers to talk about the world, and their place in it. They haven’t come far—physically, at least. Most have walked: from shared apartments, boardinghouses, and cooperative lodgings, or from red-brick mansions and smaller family homes, to a townhouse on MacDougal Street, in the middle of a busy, scruffy block just below Washington Square Park, the heart of the bohemian New York neighborhood they call Greenwich Village.

In the basement is a restaurant that everyone knows simply as Polly’s, its walls painted with sunny yellow chalk paint and hung with local artists’ work, and its wooden tables crammed close together. The whole point is to overhear your neighbors’ conversations, lean over, and join in. It’s what makes the Village the Village, this contagious buzz, sitting elbow to elbow with artists and radicals and waiting for the chef, an anarchist poet, to bang down your plate of goulash or liver and onions with his signature hiss “bourgeois pigs.”

Short-haired young women in loosely tied, batik-print tunics smoke cigarettes and flirt with long-haired young men in wire-rimmed spectacles, tweed coats, and soft-collared shirts. Upstairs, the Liberal Club bills itself as “A Social Center for Those Interested in New Ideas,” and next door, in the Washington Square Bookshop, browsers hang out for long enough that the owners protest they aren’t running a lending library. The Village isn’t a tourist attraction, at least not yet—it’s a place to live, to be, to become. Uptown, there might be more “light and space and air,” but downtown “there is another and larger and altogether incalculable element, which we might call sentiment,—atmosphere.”

At the head of the table in Polly’s, a pretty woman in her early forties with a pile of dark-gold hair raps a gavel on the tabletop and brings the meeting to order. The women around the table describe themselves as “the most unruly and individualistic females you ever fell among,” and pride themselves on their voracious interests and varied outlooks.

They are “Democrats, Republicans, Prohibitionists, socialists, anarchists, liberals and radicals of all opinions.” Sometimes they accuse each other of being “cranks on certain subjects,” but no woman obsessed by a single issue lasts long in their proudly eclectic meetings. To give each other space to doubt and to disagree, the women keep no records of their meetings. They give their secret, unruly club a name that celebrates the difference of opinion: Heterodoxy.

One thing distinguishes the chatter at this gathering from the usual lunchtime buzz: the voices are exclusively feminine. This doesn’t mean it’s much quieter than any other afternoon or that there’s no argument (or, indeed, flirting). But it does change the atmosphere, just a little. In almost every other club and society and discussion group in the bohemian Village, political or artistic or purely social, men are part of the conversation, and their voices tend to carry.

It is hard to talk over them, to interrupt or correct, without being labeled stubborn or strident. Among women, it is easier to be heard. At heart, that is the simple idea that the club’s founder, Marie Jenney Howe, uses to gather the prominent women of her acquaintance into yet another club. What it will become—a network of mutual support whose legacy runs long and deep in the lives of its members—she has no idea, on that first Saturday afternoon.

To give each other space to doubt and to disagree, the women keep no records of their meetings. They give their secret, unruly club a name that celebrates the difference of opinion: Heterodoxy.The women around the table belong to many other groups: leagues, associations, societies, and organizations of all stripes crowd their schedules. They are veterans of social reform efforts and tireless in their work for an array of causes. It’s how women, denied the vote, get things done. This club is different, however, because it isn’t trying to do anything or change anything.

A unique hybrid of the politically oriented Progressive Era women’s clubs and the freewheeling, mixed-sex discussion groups that proliferate in Greenwich Village in the early 1900s, Heterodoxy is “the easiest of clubs . . . no duties or obligations.” It offers a place to meet that is free of rules and formality, a place where ideas burst forth from intimacy. It’s enough to be, as one member puts it, “women who did things, and did them openly.” It’s enough simply to show up.

There are twenty-five charter members of Heterodoxy, one of whom is so proud of that distinction that she says she wants it carved on her tombstone. Most of them are public figures, in the way that women in professional fields at the time could often be, purely for doing their jobs. For being, if not the first or the only woman in their profession, then among the first and among the few. The majority are college educated—placing them among a tiny, elite percentage of American women—and several hold even rarer graduate degrees in law, medicine, and the social sciences.

There are pairs of sisters and pairs of lovers; women entwined by family and marriage; and those who have studied together, worked together, and marched side by side for the vote. They already know each other by reputation, if not personally— an exposé of the group calls it the “de facto star chamber council of the prominent women of New York.” Together, in that room, they represent something new, and they know it.

As I look round and see your faces—

The actors, the editors, the businesswomen, the artists—

The writers, the dramatists, the psychoanalysts, the dancers.

The doctors, the lawyers, the propogandists [sic]

As I look round and see your faces

It really seems quite common to do anything!

Only she who does nothing is unusual.

–Paula Jakobi entry, “Heterodoxy to Marie” scrapbook

Forging such exceptional lives, well outside the mainstream of expectations for women of their era, can feel daunting and isolating. It is easier in the company of others.

Yet despite the enormous impact of the club on the lives of its members, and the fame of those members in their day, the most basic facts about Heterodoxy remain elusive. We don’t know exactly where and when the club first met, only that it was sometime in 1912, probably in the spring, although some historians date it to the fall. Polly’s restaurant at 135 MacDougal Street, and the Liberal Club upstairs, which are usually identified as its first meeting places, did not open until 1913.

We know that the women met on Saturday afternoons, every other week, skipping the summer months when members went out of town to mini-Village enclaves in actual villages, including nearby Croton-on-Hudson and Provincetown, Massachusetts. At some point, meetings moved to Tuesday evenings. There were modest dues, a couple of dollars a year plus eighty-five cents for the meal, and the topic for discussion was agreed in advance. The meetings could stretch on for several convivial hours.

Because of the lack of records, we don’t know what was discussed at any particular meeting, nor who attended, though we can gather something of the meetings’ shape. The aim was not “mere clever conversation” but an organized discussion on a specific subject, from psychology to childbirth techniques, pacifism to anthropology, labor organizing to education reform.

Guest speakers, frequently invited, included Margaret Sanger, the poet Amy Lowell, Emma Goldman speaking on “Anarchy,” and Edith Ellis, a lesbian writer in an open marriage with the scandalous sexologist Havelock Ellis, speaking on the topic of “Love.” Every now and again, the doors would be opened to men for what were jokingly called husbands’ evenings. “We thought we covered the whole field,” one member recalled, “but really we discussed ourselves.”

After the second full year of Heterodoxy’s existence, the New York Tribune ran a story that claimed to blow the lid off this secretive club, divulging the names of several prominent members who belonged to the group and guests who had addressed it. The paper appeared impressed, or bewildered, that the club could operate without bylaws or written rules and that its criteria for membership were so vague—it was open to “advanced” women, but that meant pretty much whatever the members wanted it to mean.

The only other rule was the limit of forty people per meeting, a practicality to make discussion possible—although the gatherings could still be raucous. According to the Tribune, Heterodoxy was by this time meeting at the Greenwich Village Inn, at 79 Washington Place, just off Washington Square— another of “Polly’s” restaurants, a bigger space that reflected the growing fame of both the restaurateur, Polly Holladay, and the Village itself as a hotbed of countercultural ideas.

Unlike most clubs and institutions in that rapidly evolving quarter, which ran with enthusiasm for a year or two, Heterodoxy weathered the gentrification of the bohemian Village, the upheaval of World War I, and the tyranny of the first Red Scare, during which several of its members were harassed, surveilled, and arrested.

It held together through the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which splintered so many women’s rights organizations, and of Prohibition, which drove much of the artistic energy of the Village underground or overseas. It lived on beyond the death of its founder, the onset of the Depression, and the scattering of key members to Paris, New Mexico, Hollywood, or simply uptown. After a quarter century, it dimmed its lights only with the advent of another world war.

Drawing Heterodoxy together more strongly than any other idea was feminism: a new word in America in the early 1910s, if not exactly a new idea. Newspapers and magazines devoted extensive space to defining, explaining, and ridiculing the word, adapted from the French féminisme, and before long it was part of the common lexicon—a word that, depending on your point of view, spelled doom or liberation.

Those opposed to women’s rights seized on feminism as a catchall term for everything they feared: “non-motherhood, free love, easy divorce, [and] economic independence for all women.” In an era consumed by the debate over women’s right to vote, anti-suffragists fulminated that feminism was the secret end goal of the suffragists, and that the vote was a slippery slope straight to the hell of gender equality. “The implication,” as one Heterodoxy member put it, was that feminism was “something with dynamite in it.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism, by Joanna Scutts. Copyright © 2022. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.