When Writing a Novel, Forget the How and Focus on the What

Carter Bays on the Transition from Scripts to Books, and Learning to Trust His Own Style

Back when we were running How I Met Your Mother together, my writing partner Craig Thomas and I had a sign hanging on the wall of our shared office, one of those little needlepoint samplers you can order on Etsy and personalize to say anything. Ours said, “WRITING’S HARD.”

Because it is. Writing is so hard. And there’s a peculiar amnesia attached to it—the mere fact that it’s hard always, always comes as a surprise. You sit down at your computer expecting a good time, and whammo, it’s work. Why is this so hard? you ask the blinking cursor. It should be fun! After all, every novel, movie, or show you love is, in some way or another, fun.

When you watch or read something great, the fun radiates from within, like heat from a furnace, so much that you assume there must be someone behind the scenes feeding it fun in great shovelfuls. And in a sense you’re right. Fun is one ingredient in the recipe of writing. Unfortunately, the other ingredient is writing. And writing’s hard.

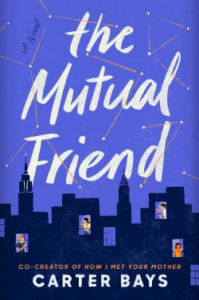

In the summer of 2014, not long after How I Met Your Mother ended, I had the idea for The Mutual Friend. Or ideas, really, since it wasn’t like it was one lightning bolt, but rather a few steady months of low-voltage static cling, as characters and observations and story beats began sticking to me like socks, until before I knew it I had cooked up an epic story about a former piano prodigy named Alice Quick who has one summer to study for the MCAT. Out of habit, I gathered up this story and turned the first few beats of it into a script for a television pilot.

But then the pilot didn’t sell. If I had to give a reason the pilot didn’t sell, I’d have to say it was because it was a pilot, and pilots don’t sell. Like, ever. It’s an age-old pageant for the professional television writer: you write the first chapter of what you hope will be a long tale, it doesn’t sell, you cry, you moan about how the business is changing and nobody takes chances anymore and besides act three never quite felt right anyway, and you move on to the next one. This cycle, if you’re very lucky, leaves you at the end of your career with two or three worthwhile successes, and a mountain of unproduced scripts in a box in your garage.

So I moved on. Only this time, even as I moved on to the next one, and then the one after that, and even the one after that, The Mutual Friend kept throbbing under the floorboards. I had brought Alice Quick to life, set her on the path to taking the MCAT, and then left her stranded. She didn’t want to be stranded. She was too determined for that. She would not be ignored, and I couldn’t ignore her. I had to find out if she actually pulls it off.

Of course, finding this out by making TV show would have required millions and millions of dollars Hollywood wasn’t ready to give me. So I’d have to tell this story another way. I’d have to write a novel.

This presented a problem. I love novels. But after twenty years in the business and thousands of Final Draft files on my hard drive, I was pretty sure writing television was, for better or worse, my craft. I had spent my allotted 10,000 hours, and was too old, and too much a father of three young children, to spend another 10,000 on anything else, aside from The New York Times Spelling Bee, and assembling my children’s Christmas presents.

Don’t write anything just because you think you’re supposed to. Write the parts you want to write, and skip everything else. Just tell the story.And frankly, I like not knowing how other people’s crafts work. I am an omnivorous fan of creativity, but especially in realms in which I boast no expertise. If there’s a harpist in a hotel lobby, I’m the guy who applauds when the songs end. If there’s a magician at a birthday party, I’m usually way more dazzled than the kids.

And no art form stokes my feelings of wonder and awe and how-dee-doo-dat goggly-eyes more than fiction. A good short story in The New Yorker hits me like one of those billiards tricks where the ball jumps over the other ball and then does a dogleg turn into the corner pocket. It’s like, what?! I don’t even particularly want to understand how it’s done, I just want to sit here enjoying the feeling of my jaw feeling the coolness of the hardwood floor. You can miss me with the How.

And writing a novel is such a big How—a Voltron, really, of many little Hows. How do you structure it? How do you know where to start the story, and where to end it? How do you know when to show and when to tell? What margins do you use? What font? How do you know where to put the he saids and the she saids?

I’d taken a few cracks at fiction over the years, and usually within a paragraph or two I’d come to an exciting moment in the story and suddenly worry that I haven’t described the room the characters are in, so I’d start talking about the furniture and the wallpaper and what’s so special about this wallpaper that I need to describe it and did they even have wallpaper in whaling-era Hawaii and it wouldn’t take long for my inner instructor-from-the-MFA-program-I-really-should-have-attended-in-order-to-seriously-do-this to tell me: “You’re doing it wrong.”

Sometimes in life you have to give yourself advice. So I gave myself some advice: Don’t worry about How. Focus on What.

When someone opens a book, of course they want pretty melodious sentences laid out like strings of pearls. Who doesn’t? But more than that, they’re there for the substance of what you have to say. The Great Gatsby is as ornately decorated as any book ever was, but it’s the doomed love, the details of Jazz Age excess, and the concrete observations about the way we all live in the past that keeps us ceaselessly coming back. Readers want you to tell them What. So tell them What! That’s your first job, How be damned!

Stop worrying about whether you’re doing it the way you’re supposed to be doing it, describing someone’s eyes in a way no one’s ever described eyes before. Don’t write anything just because you think you’re supposed to. Write the parts you want to write, and skip everything else. Just tell the story. And at the end of it, when you read it back over, you’re going to see all the little Hows you stressed out over, and all the places where you thought you were doing it wrong. And guess what? Turns out, that wasn’t you doing it wrong at all.

That was just your style.

Style! Figuring that out was a breakthrough. As soon as I internalized this idea that I’m allowed to have a style, it unlocked everything. Writing a novel wasn’t about squeezing through the eye of some needle. It was a leisurely drive on a freeway with infinite lanes.

Do you hate writing descriptions of things, and just want to write dialogue? Great! That’s your style! Roddy Doyle’s The Commitments is mostly a string of conversations, but what conversations they are! You can tell that the cadences and rhythms of human speech is where Doyle really gets his kicks, so that’s what he puts on paper. And besides, working class Dubliners starting a soul band? That’s a great What, no matter How you tell it.

Or maybe you like focusing on the details! You’re here for the décor, the food, what the characters wear…great! That’s your style. Your reader will get on board. Five pages into Crazy Rich Asians I found myself wondering, “So wait, every time a character walks in the room we’re going to stop the action and describe every stitch of clothing they’re wearing?” And by the end of the third book in the series, I was hungrily gobbling up every delicious detail about the hem of Astrid’s gown or the piping on Bernard’s jacket, because Kevin Kwan clearly has fun writing it, and that makes me have fun reading it.

I don’t want to completely minimize How. How is important. How is craft, and craft is essential. You have to learn the rules before you can break them, and nothing replaces years of study and trial and error. But if you’re anything like me, no amount of study will ever be enough, and the How will scare you off so badly that you’ll pack up a great What and go home. And that’s the worst thing you can do.

An inspiration I didn’t know I needed was Charles Portis. Portis was a real stylistic sphinx. In his five short but masterful novels, the details he chooses, the places he points his flashlight, are always surprising. Norwood, his first, sometimes feels like not so much a novel as a collection of details, but each detail feels like it has an entire novel hiding behind it.

Details like a house burning in an open field at night, or an owl hitting the windshield of a bus, both of which occupy less than a paragraph, and it’s the same paragraph, and we’re still only halfway through said paragraph before the book, and the bus, keep rolling along. I couldn’t begin to explain to you Portis’s method because his books feel so chaotically unmethodical.

Except his opening lines. And here’s what I love about him. He may go to places you couldn’t predict, but he always starts in a very straightforward way. His opening paragraphs almost always tell you what the book is about. And I don’t mean they suggest what the book is about. They don’t paint a subtle metaphor that on second reading you see is indeed symbolic of the entire text writ large. I mean he tells you, right away, what the book is about.

Like True Grit, for instance:

People do not give it credence that a fourteen-year-old girl could leave home and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood but it did not seem so strange then, although I will say it did not happen every day. I was just fourteen years of age when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.

This opening line is a basically a book report of the novel you’re about to read. I’d say “no spoilers,” but it’s all right here, right down to establishing the villain and giving him a first and last name. Of course, you can argue Portis is doing many things here below the surface, like endowing his protagonist with her signature plainspokenness and her need to display an ironic detachment toward violence, but I think it’s simpler than that. I think he just has a great story to tell, so he’s kicking it off by telling it.

Portis, a famous recluse, didn’t leave behind much in the way of shop notes, so I have no idea how the man wrote. But if I were to CSI my way to a forensic explanation of this line, it would go like this:

Portis has an idea for a novel. It’s the story of a fourteen-year-old girl who avenged her father’s death. So he sits down at his typewriter and taps out the first line of that novel:

One time a fourteen-year-old girl avenged her father’s death.

That’s the What, and it’s a doozy! I mean, are you kidding me? Avenging a father’s death? In the history of literature, from Hamlet on down, that’s maybe the biggest What there is. So now that his What’s on the page, he can relax, smoke a cigarette because it’s Arkansas in the 1960s, and set about doing the fun part: The How. One by one, he starts hanging ornaments on the Christmas tree. What if it’s the girl telling the story? What if it’s in the wintertime?

What if the bad guy makes off with two gold pieces that were in the dad’s trouser band? What if the bad guy’s named after my 7th grade math teacher who I hated, Mr. Chaney? These are the kinds of questions you ask while rewriting. They’re fun questions to ask, and even more fun to answer. Rewriting is a treat. Every second I spend rewriting, I’m grateful to the person who put this rolling boulder in motion: Past Me, who did the hard part and gave Present Me something to rewrite, by setting aside How and just saying What.

So that was it. Forget about How, focus on What. I realize this is not necessarily advice for everyone. In fact, I might very well be the only person on earth for whom it was useful. It might even been a lie. But for me, it was Dumbo’s feather— the possibly-magical thing that allowed me to fly.

________________________________

The Mutual Friend by Carter Bays is available now via Dutton.