Seamus Heaney on William Wordsworth's One Big Truth

An Indispensable Figure in the Evolution of Modern Writing

As a child, William Wordsworth imagined he heard the moorlands breathing down his neck; he rowed in panic when he thought a cliff was pursuing him across moonlit water; and once, when he found himself on the hills east of Penrith Beacon, beside a gibbet where a murderer had been executed, the place and its associations were enough to send him fleeing in terror to the beacon summit.

Every childhood has its share of such uncanny moments. Nowadays, however, it is easy to underestimate the originality and confidence of a writer who came to consciousness in the far from child-centred eighteenth century and then managed to force a way through its literary conventions and its established modes of understanding: by intuition and introspection he recognized that such moments were not only the foundation of his sensibility, but the clue to his fulfilled identity.

By his late twenties, Wordsworth knew this one big truth, and during the next ten years he kept developing its implications with intense excitement, industry and purpose. During this period, he also elaborated a personal idiom: “nature” and “imagination” are not words that belong exclusively to Wordsworth, yet they keep coming up when we consider his achievement, which is the largest and most securely founded in the canon of native English poetry since Milton. He is an indispensable figure in the evolution of modern writing, a finder and keeper of the self-as-subject, a theorist and apologist whose Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1802) remains definitive.

Wordsworth’s power over his reader stems from his success in integrating several potentially contradictory efforts. More than a century before Yeats imposed on himself the task of hammering his thoughts into unity, Wordsworth was fulfilling it with deliberate intent. Indeed, it is not until Yeats that we encounter another poet in whom emotional susceptibility, intellectual force, psychological acuteness, political awareness, artistic self-knowledge, and bardic representativeness are so truly and resolutely combined (William Blake also comes to mind, but he does not possess–indeed he would have disdained–the “representativeness.”)

Take, for example, a poem such as “Resolution and Independence.” Democratic, even republican, in its characteristic eye-level encounter with the outcast, and in its curiosity about his economic survival. Visionary in its presentation of the old man transfigured by the moment of epiphany. Philosophic in its retrieval of the stance of wisdom out of the experience of wonder. Cathartic in the forthrightness of its self-analysis. Masterful in its handling of the stanza form. Salutary—not just picturesque—in its evocation of landscape and weather, inciting us to perceive connections between the leech-gatherer’s ascetic majesty and the austere setting of moorland, cloud, and pool. In a word, Wordsworthian.

Furthermore, “Resolution and Independence” exemplifies the kind of revolutionary poem Wordsworth envisaged in the Preface. It takes its origin from “emotion recollected in tranquillity;” that emotion is contemplated until “by a species of reaction the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced and does actually exist in the mind.” What happens also in the new poetry (again, these are the terms of the Preface) is that a common incident is viewed under a certain “colouring of imagination;” ordinary things are presented to the mind in an unusual way and made interesting by the poet’s capacity to trace in them, “truly though not ostentatiously, the primary laws of our nature.”

Faced with the almost geological sobriety of works such as “Tintern Abbey,” “Michael,” “The Ruined Cottage,” and the celebrated “spots of time” in The Prelude, it is easy to forget that they are the work of a young man. These poems, which enabled Wordsworth to speak with such authority—not just about the creative process but about the attributes of a poetry adequate to contemporary conditions—were written while he was still in his twenties. Yet the note is sure, the desire to impress absent, and the poems thoroughly absorbed in their own unglamorous necessities.

One of the reasons why Wordsworth’s poems communicate such an impression of wholeness and depth is that they arrived as the hard-earned reward of resolved crisis. The steady emotional keep beneath them has known tempestuous conditions. They are songs of a man who has come through, one in whom William Hazlitt noted “a worn pressure of thought about his temples, a fire in the eye . . . an intense, high narrow forehead, a Roman nose, cheeks furrowed with deep purpose and feelings”. That was in 1795, when the poet had almost weathered the storm and was lingering in the south of England, in the vernal clearings of Racedown in Dorset.

Behind him lay a childhood and schooltime full of luminous and enlarging experiences around Hawkshead, in the mountains of his native Cumberland. He had grown up visited by sensations of immensity, communing with a reality he apprehended beyond the world of the senses, and he was therefore naturally inclined to accept the universe as a mansion of spirit rather than a congeries of matter. He had also grown up in a rural society where the egalitarian spirit prevailed and people behaved with reticence and fortitude in a setting that was both awesome and elemental. All of which predisposed him to greet the outbreak of the French Revolution with hope and to espouse its ideals:

If at the first outbreak I rejoiced

Less than might well befit my youth, the cause

In part lay here, that unto me the events

Seemed nothing out of nature’s certain course,

A gift that rather was come late than soon.

The natural goodness of man he inclined to take for granted, so it did indeed seem possible that the removal of repressive forms of government and the establishment of unmediated relations between nature and human nature could lead to a regeneration of the world. Certainly, when Wordsworth and his friend Robert Jones went on a walking tour through France in 1790, the summer after the fall of the Bastille, they could not miss the atmosphere of festival and the feeling that the country had awakened.

Jones! as from Calais southward you and I

Went pacing side by side, this public Way

Streamed with the pomp of a too-credulous day,

When faith was pledged to new-born Liberty:

A homeless sound of joy was in the sky:

From hour to hour the antiquated Earth

Beat like the heart of Man: songs, garlands, mirth,

Banners, and happy faces, far and nigh!

When he wrote this sonnet, twelve years after the events it describes, Wordsworth was only thirty-two, but he had already completed the Dantesque journey into and out of the dark wood. Having come near to breakdown in the early 1790s because of emotional crises (the outbreak of war between England and France separated him from his French lover and mother of his child) and political confusions (the Reign of Terror had dismayed supporters of the Revolution), he was helped back towards his characteristic mental “chearfulness” by two indispensable soul-guides. His Beatrice was now his volatile and highly intelligent sister Dorothy, his Virgil the ardent philosophical poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and it was in residence in France for an annus mirabilis, composing the poems that would make up the 1798 edition of Lyrical Ballads, the epoch-making volume that initiates modern poetry. A trip to Germany followed, during which William wrote several of the “Lucy” poems, and the first draft of his autobiographical masterpiece, The Prelude. Finally, the Wordsworth country as we know it came into being when the poet and his sister settled in the Lake District, at Dove Cottage in Grasmere, at the end of 1799.

When they moved out in 1808, The Prelude existed as a major poem in thirteen books, William had married Mary Hutchinson and was already the father of four children, the Lyrical Ballads had reached a fourth edition, a two-volume collected edition of his poems had appeared in 1807, and, all in all, the work of “the essential Wordsworth” was mostly completed.

In 1813 he would move to the stateliest of his addresses, Rydal Mount, an imposing house between Grasmere and Ambleside, where he and his family (still accompanied by Dorothy) lived until his death in 1850. The poet suffered personal losses in his prime—a son and a daughter, Thomas and Catharine, died in 1812—and his final years were darkened by Dorothy’s mental breakdown and the death of another daughter, Dora, in 1847; but this had little effect in lessening the general impression that as the years proceeded Wordsworth became more an institution than an individual. It is an impression reinforced by the sonorous expatiation of his later poetry and the roll call of his offices and associations—friend of the aristocracy, Distributor of Stamps for Westmoreland, Poet Laureate. He had lost the path that should have kept leading more confidently and deeply inward; still vivid as an intelligence, nationally celebrated, domestically fortified, he ended up industriously but for the most part unrewardingly marking time as a poet.

It was Wordsworth’s destiny to have to endure and try to make sense of the ebb of his powers and the flight of his vision. Yet he had schooled himself in the discipline of maintaining equanimity in the face of loss, and the ultimate rewards of his habit of patience are to be found in masterpieces of disappointment such as the “Immortality Ode” and “Elegiac Stanzas”. But equally the reader rejoices in the occasional unapologetic cry of hurt, so immediate and so powerful—as in “Extempore Effusion”—that it overwhelms his customary resignation. As a poet, he was always at his best while struggling to become a whole person, to reconcile the sense of incoherence and disappointment forced upon him by time and circumstance with those intimations of harmonious communion promised by his childhood visions, and seemingly ratified by his glimpse of a society atremble at the moment of revolution.

Excepted from William Wordsworth: Poems Selected by Seamus Heaney. Used with permission of Faber & Faber. Copyright © 2016.

Excepted from William Wordsworth: Poems Selected by Seamus Heaney. Used with permission of Faber & Faber. Copyright © 2016.

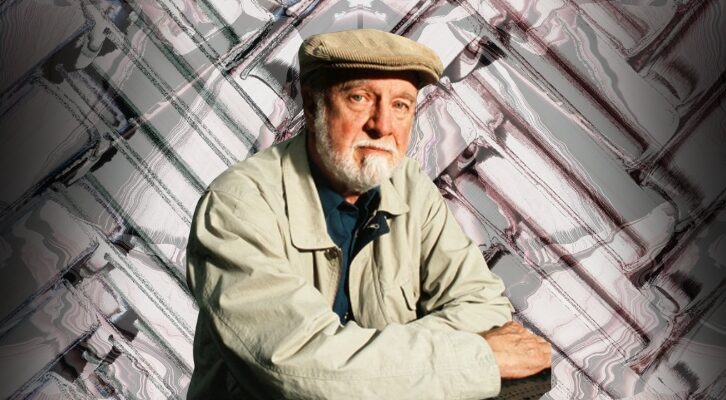

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney is widely recognized as one of the major poets of the 20th century. A native of Northern Ireland, Heaney was raised in County Derry, and later lived for many years in Dublin. He was the author of over 20 volumes of poetry and criticism, and edited several widely used anthologies. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995 "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past." Heaney taught at Harvard University (1985-2006) and served as the Oxford Professor of Poetry (1989-1994).