Saving Our Trees, Saving Our Animals

Dr. Kinari Webb on Partnering with Rainforest Communities in Indonesia

A year after I was stung by the deadliest creature on the planet – a box jellyfish, my survival was still in question. But seeing death face to face was making it clearer that I needed to expand my work of addressing the health of the planet by enacting the solutions of rainforest communities. That listening had led me to found a program in Indonesian Borneo where people could learn sustainable agriculture and pay for healthcare at a clinic where communities got discounts for stopping logging. As I saw the dramatic impacts, hope for our planet began to seep in.

*

Back in Bali, my health deteriorated, and it was very unclear how long it would take me to recover or if I ever would. Facing mortality yet again was forcing me to be as honest as possible with myself and try to learn to listen more to my limits. It was strange to have expectations for my own life shrinking while my understanding of possibilities for the earth were expanding.

I recalled a conversation I once had with a new volunteer. We were traveling out to a village, and as we rounded a curve in the road, we were greeted by an exquisite view of the forest stretching up into the mountains of the park. The volunteer asked me if I really thought Gunung Palung National Park could be saved—and even if it could, would it really matter anyway? Wasn’t this all hopeless? Why was I even trying?

My answer at the time was quite pessimistic. “I will be very surprised if we can decrease the illegal logging. And if we can, and if we do manage to save some of the biodiversity, honestly, I believe that it will be for some post-human world. It looks very likely to me that humans will destroy themselves. Population growth, ecological collapse, increasing divisions between rich and poor, and an unwillingness to recognize what’s happening—it’s the perfect storm.” I took a deep breath and looked at her. “But the only thing in my hands is this day, this life saved, this tree saved. I believe that we still have to give our whole lives to doing the right thing, in whatever way we can. We may be smashing just one small hole in a huge wall. But someday—like the Berlin Wall—maybe enough of us will break down parts of our false sense of separation from the natural world, and we will be free. All we can do is try, even if it is hopeless.”

Most days, I believed my prediction of doom; I saw humans as inhabiting a kind of petri dish, in which we would continually expand our use of resources until they ran out. Those were the beliefs I lived with daily (and which Cam reinforced). But recently, a feeling of dangerous hope had been seeping in. I say dangerous, because, if there was some real chance of averting disaster, I knew I would have to face up to that quiet, persistent voice that told me that transformation might be possible on a vastly bigger scale and that I should start working on that broader level.

The volunteer asked me if I really thought Gunung Palung National Park could be saved—and even if it could, would it really matter anyway?As humans, we struggle to grasp how radically things can change; as soon as one problem is solved, we focus on the next. I knew this in my own soul. I tend not to look back, to remember where we started from, or to give myself credit for all the changes in my own life. I could only see the next issue to work on. We forget to recognize how far we have come: from a world essentially continually at war, to the greatest period of peace the world has ever known; billions have been lifted out of extreme poverty; life expectancy keeps rising; and women now can vote in every country in the world (New Zealand was the first in 1893 and Saudi Arabia the last in 2015). Obviously, we still have much yet to do, but we should also see where we have come from (Hans Rosling has fabulous interactive graphs that illustrate all these points). However, much of the progress of humanity has come at the expense of the natural world and only because of the use of fossil fuels.

The problem is, in most rights revolutions, a core group of disenfranchised people usually begin by putting themselves on the line. But the birds, insects, orangutans, orchids, and rivers can’t argue on the streets or in the courts that their well-being should be considered. Even so, many humans are stepping forward to advocate for them and for the health of our planet. I personally know many, many people who are passionately committed to defending the natural world and even more who are its silent supporters.

Nor is this true only among the wealthy of the world. I will always remember one woman who came into our clinic from a nearby village; she puzzled our registration manager when she didn’t want to be seen as a patient but asked to see me—and refused to say why. When I sat down with her, she started by saying how much she appreciated that the clinic cared about the natural world as well as saving people’s lives. Then she made me promise that if she told me something, I would make sure that the right people got the information. I agreed. With some trepidation, she told me that someone she knew had killed an orangutan, and that the male’s head was still in his house. By this time, a few other staff members had gathered around to hear her story.

Some men she knew in her village had been hired by a businessman in the capital city of Pontianak to hunt an orangutan. Apparently, the trader planned to sell the meat at very high prices to rich people who wanted to eat exotic bushmeat. The hunters went into the forest and searched for days until they found a big male orangutan in a tree. She told us that she had heard how the first shot only wounded him and that, before they managed to kill him with another bullet, the orangutan used some leaves to try to stop the bleeding. “He was just like a human! We use leaves from the forest to cure our ailments as well. He was using traditional medicine! And after they brought his body to the village, I saw his hands. They were just like human hands. I am so angry at them for killing the orangutan. How could they do that? I don’t want to turn them in, but it isn’t right. What they have done is just wrong.” As she spoke, tears ran down her face.

The staff and I were crying as well. Many of us were thinking about Riki, the baby orangutan whom we had treated in our clinic. International Animal Rescue, another nonprofit near us that cares for orangutans who were losing their habitat to the palm oil plantations encroaching south of the park, brought him in while their veterinarian was traveling. Riki had been rescued after his mother was shot trying to escape from the bulldozers. He was severely dehydrated, and our nurses had no trouble finding a vein for an IV (the veins were in exactly the same place as in a human baby). It appeared that he may have also been shot, because I felt small, hard objects in his belly. We started him on antibiotics after consulting with the local Indonesian veterinarian, and he perked up enough to be taken back to the recovery center. Sadly, though, Riki had not survived, and an autopsy indeed showed bullets in his abdomen. Our tears were not only for these two but all the thousands of orangutans dying each year in Borneo.

The birds, insects, orangutans, orchids, and rivers can’t argue on the streets or in the courts that their well-being should be considered; many human beings are stepping forward to advocate for them.After sharing her story, the woman proceeded to give us exact directions to find the remains of the male orangutan. That information (along with other details gathered by another nonprofit called Yayasan Palung) was critical in making a case against the bushmeat trafficker, who was finally arrested with untold blood on his hands. Catching this culprit had a widespread impact, since these traffickers are actually rare. That woman’s bravery, along with a dedicated community, helped stop a poaching ring that operated far beyond Gunung Palung.

There will always be some people who are willing to do almost anything for money, whether out of desperation or greed. But once social norms change enough, the public no longer tolerates activities that were once accepted. When we first started our work around Gunung Palung, most of the communities already wanted to save rainforests—even though logging was still unchecked. I’m not sure where these beliefs came from, but they were quite strong. In our survey, 92 percent of non-loggers were opposed to cutting down trees, and amazingly, two-thirds of the loggers agreed. That meant that the large majority of people who were logging didn’t even consider it a legitimate activity. They also nearly all said they would prefer alternative work. This is notable because there is considerable variation in the ethnic groups surrounding the park with successive waves of migration into the area. Yet there wasn’t any variation by religion or race in their desire to still have thriving rainforests near them.

If one defines Indigenous people as those who believe they belong to the land and not the other way around, all these groups would likely fit in that category. This worldview likely has very deep roots in all the cultures in Indonesia but is also reinforced by living daily in proximity to the natural world and being dependent on it. However, there had also been about ten years of educational and conservation outreach work done by the nonprofit Yayasan Palung, who had helped break the poaching ring. Their work may have helped tilt the scales before we began our radical listening sessions. (Yayasan Palung was started by another orangutan researcher, Cheryl Knott, who has continued to conduct research through Harvard and Boston universities.)

But even though these communities wanted to protect the forest, that wasn’t enough; on their own, they didn’t have some of the knowledge or the resources to bring about positive change within changing economic realities. In theory, these problems could have been solved by the government (especially if they knew what the community-determined solutions were).

Our local regency had over the years been increasing access to medical care and even providing free services to many patients, but still there often ended up being unexpected expenses, especially if a patient was referred to another regency. I wondered if Indonesia carried through on its plan to provide universal health insurance by 2022, whether that might have a big impact on illegal logging throughout the country. They planned to have citizens pay monthly premiums, but maybe someday we could convince them to allow people to be able to pay their premiums with seedlings. It would even be possible in an integrated government system for forest communities to get discounts for their premiums based on logging rates.

In my perfect world, these discounts and the seedlings would be paid for by carbon offsets from companies and governments around the world that cared about a sustainable future for us all. Indonesia would get help with health care, and the world would get a healthier planet.

Something similar could work in the developed world, too, where taxes for universal health care could be prorated based on carbon footprint. This would make visible the true link between human and environmental health and how we all have an obligation to both.

Would we realize that we simply had to learn to live in balance with our earth or face an un-survivable future? Would our love and compassion for the natural world triumph over our desire to look the other way? My reading and reflections during this forced rest were starting to shake my belief that this change was impossible.

Maybe Indonesia could lead the way in showing the world how to do it.

_______________________________________

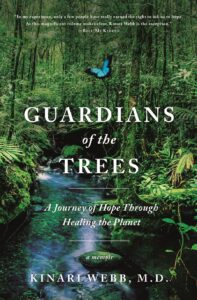

Excerpted from Guardians of the Trees by Dr. Kinari Webb. Copyright © 2021 by the author and reprinted by permission of Flatiron Books.