Between the Lines: What Is Missing in the Diversity in Publishing Discourse

Thomas Gebremedhin Considers Text and Subtext in the Publishing Industry

On Saturdays in late ’90s, my father, a taxi driver, would pool his tips for the week and take me, a child too precocious for his own good, to a local bookstore in search of my next read. Together, we silently wandered the store, picking up paperbacks and inspecting their pages. On shelves that often faced the front windows sat the works of Don DeLillo and E.L. Doctorow and Virginia Woolf, while giants like Toni Morrison and James Baldwin and J. California Cooper, architects who built entire worlds depicting the plurality of the Black American experience, were relegated to a corner labeled “Black literature.” To get from one section to the next, I walked down aisles that felt as long as city streets.

*

Recently, following the departure of several high-level editors of color—particularly women of color—from various publishing houses, the conversation about diversity in the industry has been reignited. I’ve been surprised by the complicated feelings it’s raised in me, a Black, queer editor who has worked in magazine and book publishing for nearly a decade, the insecurities I thought my wins had extinguished, the fear. Certainly, diversity is a real and crucial issue in publishing. I know this all too well; I value it and try to hold the door open for others. As Toni Morrison once said, “The function of freedom is to free somebody else.” (Morrison is recognized by most readers for her novels, which are among the greatest of all time, but she was also a book editor, the first Black female editor in the history of Random House.)

I recently read a New York Times article entitled “‘A Lot of Us Are Gone’: How the Push to Diversify Publishing Fell Short.” It is not the first instance of such an article, and it will not be the last. But it has been uncomfortable to read stories about Black editors that hinge entirely on their subjects’ race, flattening individuals and cohorts, effacing their sensibilities. I feel abridged.

And it has made me question how the work of Black editors continues to be received. Where do we sit on the bookshelf of public discourse?

*

I joined Doubleday as vice president and executive editor in 2020. It was the year of the George Floyd uprisings, a time of sickness, both physical and psychic. Prior to Doubleday, I was an editor for The Atlantic, where I worked across genres—reportage, criticism, essays, fiction. Often, the magazine’s overall political coverage felt out of step with my own leftist ideals, but I was fortunate to find mentorship among the editorial staff, and, over time, my own instincts and tastes sharpened and coalesced, in response to the work. But as Covid surged, my own hypochondriacal neuroses pushed me toward the edge, my hands blistered over from too much washing. I thought about life and legacy as never before. So, when the opportunity in books presented itself, the question for me was much bigger, more poignant and loaded, than your average career change.

It has been uncomfortable to read stories about Black editors that hinge entirely on their subjects’ race, flattening individuals and cohorts, effacing their sensibilities. I feel abridged.The first book I managed to finish during lockdown was Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (Robinson had been my thesis advisor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop). The novel depicts the final days of a dying reverend looking back on his life. Talk of death was all there was to talk about during those dark days, and yet I was comforted by a critically ill man offering his final testimony, reflecting and interrogating his successes and his failures, his values. Gilead put me back together again, and I dreamed of one day doing the same for someone else. I pictured my father and mother pulling a book from a shelf, a book that I had edited, and reading it to one another as they had once read to me. (My mother still favors the maxim, “Language is power.”)

With that, I left my plum magazine job to honor my lifelong obsession with literature.

But despite my excitement about what possibilities a career in publishing might hold, I struggled to tune out the cultural murmurings that dominated our moment: that certain hires were only made to satisfy a diversity quota. Black editors like me and others who were being courted by the industry were, according to the media and even other book editors, a dubious answer to an annoying problem. Soon, the celebratory rush I felt upon accepting the Doubleday job faded and was overshadowed by self-doubt—a toll that must always be paid by people of color.

Racism plagues publishing, like most industries, presenting itself explicitly and not. Liberals and centrists abound—avid readers of Black and Brown writers who purport to be progressive eventually reveal themselves to be blind in the most critical ways. I, like most of my cohort, routinely confront microaggressions.

Once, while I was walking on another floor at the Penguin Random House offices, an employee handed me a package to be messengered.

Another time, I was invited to lunch with a (now former) white colleague. They vented to me about a Canadian editor with whom they shared a book. The editor, my colleague told me, was Black and hired around the same time as me. But she was not good on the sentence level and would likely be fired soon. The subtext blared: Be careful. You’re next.

*

During my first year, I took my time with acquisitions, careful not to be boxed in by agents with cynical agendas or buy a book simply to alleviate my anxieties. I am fortunate to work with a publisher who gave me the space and freedom to settle into my new role at my own pace. It’s a collaborative relationship the likes of which not everyone is afforded.

My first acquisition at Doubleday was Hua Hsu’s memoir Stay True, which went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award in autobiography. It was on the New York Times Bestseller list for seven weeks, and it was recently named one of the best books of the 21st century by The New York Times Book Review, making it among the most critically acclaimed books in recent memory. This June, I published my first work of fiction, Beautiful Days by Zach Williams, which Barack Obama selected as one of his favorite reads of 2024. I can recall handling the first warehouse copies of both books, flipping to the acknowledgements page and reading the author’s words about me. At least, I thought to myself, if I do nothing else in my life, I will live on in these pages forever.

There is an artistry to editing that is not often associated with Black editors and left out of the discourse on diversity. Editors of color are more often credited with shepherding works of sociological importance; “Black literature” is treated like autoethnography. I take pride in my job. I bring considerable craft and ingenuity to the projects that land on my desk because it is not simply about spotting trends but rather making a damn good book.

Editing Stay True was a nourishing experience. It is a memoir about growing up and finding one’s place in the world, about the Bay Area counterculture of the ’90s, about building an identity free of the dictates of race. It is about self-discovery, rediscovery, and the often-rocky path taken to discover life’s moments of sheer beauty. When I read the manuscript, Hua’s voice was a beacon, guiding me across my sea of angst to solid ground. He found me when I needed him most.

The brilliance of Stay True—the reason, I think, it landed the way it did for readers—is that it rejects tidy binaries: it is a universe of many things all at once. I worked closely with Hua to deepen the story he wanted to tell. We braided together challenging ideas, we disagreed on edits, and eventually, in my small way, I helped him see his vision through to the end.

Since the publication of Stay True, I have noticed the industry’s perception of my tastes became more multidimensional, although there are still those agents who will never think of me as a potential editor for a biography of Chaucer or a history of 20th century physics. During those early days on the job, I had to push back against the small-mindedness—the lack of imagination—that I was met with by these agents (though, of course, there were those who engaged with me with earnestness and savvy from the very beginning).

And my list has grown, encompassing my wide-ranging interests: film, politics, science, technology, personal narrative, fiction. Earlier this year, I published a work of criticism examining the impacts of social media algorithms on arts and culture. Around the same time, I acquired an intellectual history of the roots of Zionism. I recently completed edits on a memoir about the convergence of motherhood and technology. Over the next few years, I will publish a biography of Ursula Le Guin; a historical novel set during the interwar years in Germany that centers a Black cabaret performer; a righteously angry study of neoconservative politics; and a cultural investigation on the ways women survive and heal from violence.

It would be impossible to capture the true plurality of experiences of Black people in publishing in a series of topical essays, but shaping a neat narrative at the expense of the texture of truth won’t suffice.My background informs how I read a manuscript, the sounds I hear in a text when certain notes are played, my commitment to elevate voices shunted to the margins. But my identity is not limited to my Blackness. Queerness and nationality and generation—my socioeconomic upbringing—also shape my reading of a text. These identities work in tandem and yet, like different colors of light in a prism, they refract in distinct way. A rule of mine? I must run into myself in everything I acquire.

The range of my interests as a reader, a thinker—as well as those of other editors of color—speaks to what is missing from the current discourse. On August 21, the writer Brandon Taylor took to Instagram to rightfully question this omission. Articles like one that had recently appeared in the New York Times presuppose “to an insane and limiting degree what a black editor might acquire or be interested in or what they bring to the table.” Taylor also pointed out that some of the most celebrated books on Black life today have been edited by white editors. This is undeniably a symptom of the larger problem of the makeup of editorial departments across publishing, but Taylor’s line of thought foregrounded a very real concern, the idea that perhaps we should begin to ask why many white editors are not acquiring more innovative, interesting books written by people of color and other marginalized voices. Too often, the burden of fixing these ossified corporate and cultural structures falls on us, the ones with the most to lose.

And then there is the question of the range of experience that receives the attention of, specifically, white gatekeepers. Publishers, it is apparent, feed on Black trauma—Percival Everett captures the practice brilliantly in his novel Erasure; corporations race one another to commodify our most painful experiences. No person of color moves through this world without bearing the scars of trauma. But there is a splendor to our lives, too.

When I was five or six, my mother and father and I walked to our car, which was parked outside our apartment. The windshield was caked with orange, chunky vomit. On the trunk, the letters “KKK” were etched into the paint.

This is one experience that stays with me.

I remember, too, an even earlier memory. My father returns home from work, this time to an even smaller apartment, and wakes me up around 2 AM, when his taxi shift ended. With fanfare, he presented me with a Little Mermaid Barbie. I played with the doll in the bath, her red nylon hair weightless in the water.

*

Racism is pervasive in our industry. Racism is pervasive in America and the world writ large. Its tendrils are inescapable. Like a predator, it stalks people of color, follows us into every room we enter. The quality of life for us, especially junior level employees and women, is near impossible to fathom for anyone who does not identify as such. We are reduced, tokenized, and condescended to. But the coverage of these issues is now guilty of the same crimes: the material reality is a far more complicated story than the simple rise and fall of any publishing executive. An utter incuriosity overshadows basic questions: What are the external and internal forces, alongside race, that contribute to the success—or downfall—of an editor? Was their manager supportive? Were they a good manager? What is their sense of aesthetics, culture, politics? How do they advocate for their books? What is their relationship to their authors?

Sexism, without question, plays its part, too, and I recognize that my gender grants me privileges in moving through the world.

Now, of course, it would be foolish and counterproductive to deny the cynicism that informed hiring practices in 2020, or the lack of support (financial, emotional) that many editors of color feel day to day. But to reduce the story to a Manichean simplicity is a double crime: it highlights an oversimplified version of the truth and intentionally ignores the experiences of those of us who remain. Our successes, sure, but also the challenges that we continue to face. And what about Black booksellers, publicists, and marketers? When the story becomes solely about skin, elevating only a handful of voices and anointing them as authorities, we as people of color—all of us—are not actually the story but merely window dressing.

It would be impossible to capture the true plurality of experiences of Black people in publishing in a series of topical essays, but shaping a neat narrative at the expense of the texture of truth won’t suffice. Take, for instance, the article “‘A Lot of Us Are Gone’: How the Push to Diversify Publishing Fell Short.” In response to that headline, the question becomes “Did we do a good job?” The “we” there is not Black people, it is the white middle management that oversees us—the putatively liberal establishment that wields power. But the reporters of that story and others like it continue to rely on the same sources to construct a tidy, tendentious narrative that is easy for white readers to metabolize, are complicit in allowing the establishment to contextualize its failures without admitting culpability, an admission that we are owed.

*

The initial cover for Filterworld by Kyle Chayka—the social media algorithm book I published earlier this year—depicted an illustration in the vein of a Flat Stanley, a figure reminiscent of the paper doll chains that decorate children’s classrooms, one cut-out indistinguishable from the next. We ran with an alternative cover, but it is that first image that I have conjured again and again over the last several months, as I have witnessed the stultifying conversations around recent layoffs. Somehow, by no choice of my own, I feel flat.

It is essential that our conversations surrounding the dearth of people of color in publishing attempt to highlight our dimension as well as the full and complicated scope of the crisis in the industry. It is equally important to consider the lack of Black and Brown junior publicists or production assistants as it is to consider the careers of Black executives. Because the junior positions in publishing comprise the unsung heroes of the grand project of bookmaking.

The pressures of my job, and the expectations placed upon me—corporate and cultural pressures, too—have a flattening effect, yes, turning me into something like the Flat Stanley figure from the original Filterworld cover. But I know the figure has a mind, varied and complex passions. It has fingers and joints. It has a heart and an aim and an awareness of its own place in the world. A definition of itself.

I know that figure has a face.

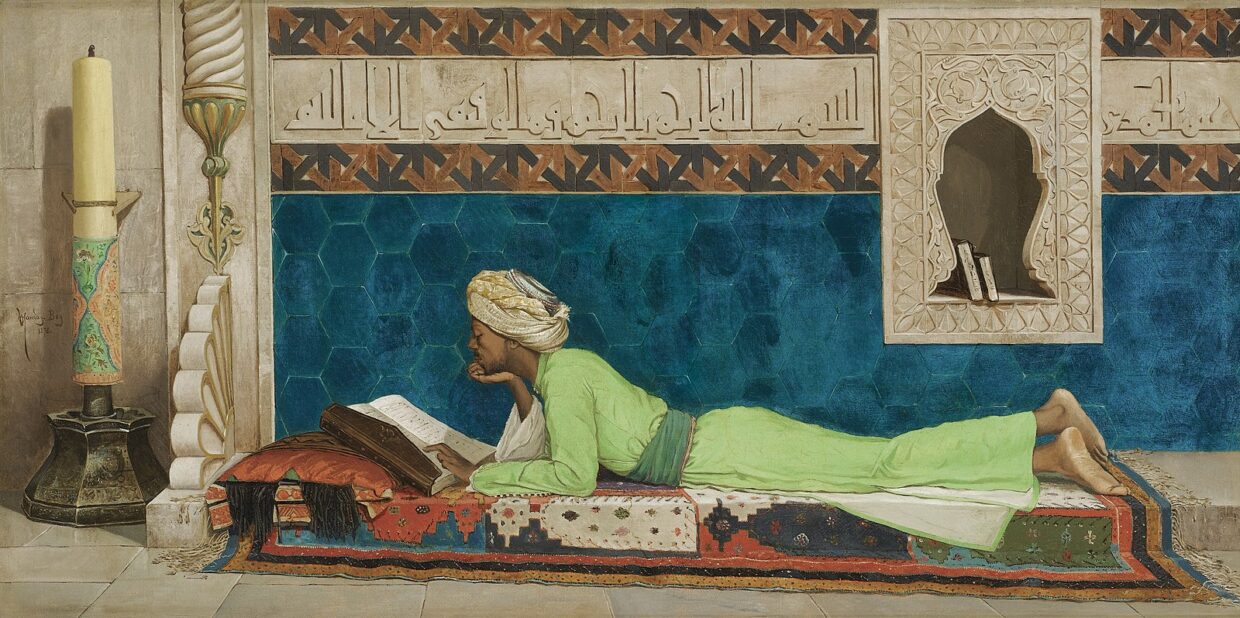

Image credit: The Scholar, Osman Hamdi Bey (1878)