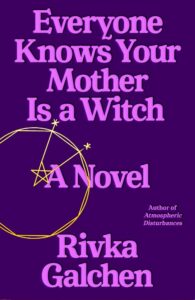

Rivka Galchen Talks Writer’s Block and Her Pandemic Cat

Lit Hub Speaks with the Author of Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch

Rivka Galchen’s sophomore novel Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch draws upon real historical documents to tell the story of Katharina Kepler, a widow who is accused of being a witch and, in turn, relays her account of herself to her next-door neighbor Simon, a mysterious recluse. Below, Galchen answers a few questions about her writing process and favorite books.

*

Literary Hub: What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Rivka Galchen: No one ever asks me about my cat. She’s a pandemic pet, so she hasn’t been around for many interviews, true. She hunts pipe cleaners and small rubber erasers. She likes to spend time in boxes, paper bags, and also in doorways. She looks like an arctic fox and sleeps like an arctic fox. I’ve long wanted an excuse to refer people to the section of the poem Jubilate Agno by Christopher Smart, in which he praises his cat: “For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.” I have lived my life skeptical of cat people—I’m a dog person, though sadly without a dog at the moment—and now, here I am, a cat person.

LH: How do you tackle writers block?

RG: I find reading to be a remedy for: anxiety, rage, boredom, writer’s block, even allergies. I do best when I’m spending many more hours reading than writing. I sometimes think of writing as just a very intense form of reading, it’s just that you have to generate the words that you’re going to then read. I like to read at night in bed, until that magic moment when I’m deceiving myself into thinking my eyes are still open, that I’m still reading, but really I’m just dreaming that I’m reading. In that way, I think sleep is another good way through writer’s block. Especially little naps.

LH: Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

RG: There was about a decade of my life when I would turn to Epitaph of a Small Winner by Machado de Assis, The Third Policeman by Flann O’ Brien, and The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon. I’d open those books to anywhere, read a little bit, and feel crackly and electric. Even a half-sentence in those books gives joy, or a little laugh, or a little something.

I find reading to be a remedy for: anxiety, rage, boredom, writer’s block, even allergies.That reading has shifted for me in the past year and a half or so. Probably because everyone’s reading has shifted in this past year and a half or so. I’ve been reading books that are loosely woven, but layer on top of each other, which is a long-winded and somewhat pretentious way of saying I’ve been reading serial books. The Wooster and Jeeves books by PG Wodehouse, the mysteries of Agatha Christie and of Rex Stout. When you read the ‘next’ book, you’re really reading the same book again, but also it’s a different book, but not that much more different than reading the same book at a different moment in your life. It’s sort of like painting layer after layer of the same color paint. But the color intensifies, or at least alters, as the layers accumulate. The individual sentences—that’s not where the magic is for these books. (Though actually there are a lot of magic sentences, especially in dialogue, in the Wodehouse books.) The magic instead is sort of interstitial.

It brings me back to one of the many little details in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman that I love. One of the (essentially mad) policemen (in hell) explains that when you’re born, you take on the color of the wind at that moment. It’s on you as a very, very, very thin cloth of a particular color. You can’t see it at first. Then over time, each year, another thin layer—same color. Until eventually it’s like you’re an unmistakable pigeon grey, or grapefruit blush, or whatever it is. Now that idea—that’s so goofy, but also so great. Today it makes me think that it’s the very best description of how one grows into one’s essential character over time. It was there from the start. Your experiences are more like a filter that the character flows through, but the character remains essential, your algorithm.

The Third Policeman also has an excellent backstory that writers will recognize. O’Brien’s publisher rejected it, finding it too weird. O’Brien then pretended he had lost the manuscript, because he was so embarrassed and ashamed.

LH: What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

RG: My earliest book memory is of the children’s book Ticki Ticki Tembo. It’s the story of a little boy named Ticki-Ticki-Tembo-No-Sa-rembo-Chari-Bari-Ruchi-Pip-Peri-Pembo, and because his name is so long he nearly drowns in a well, because when his little brother runs to ask for help from a series of people, it always takes so long for him to narrate what happened. We had very few kids’ books in the house, and this was one of them. The book had silly language, and it had repetition, and it had a spooky, ambiguous ending, in which it’s unclear if the boy dies but is still present as a ghost, or if, in the end, he survives. The words say one thing and the illustrations seem to say another. My mother still refers to it as “one of the few interesting books,” because she had an aversion to most other kids’ books.

The book says it’s based on an ancient Chinese myth, I’ve also been told it’s an old Yiddish story, I’ve also been told it’s all invented nonsense. Probably all those things are true, maybe that’s part of why it reads as so elemental, and stayed with me all these years. It also feels like one of those Russian fables against class pride? The kids’ version of The Nose.

LH: Is there a book you wish you had written (why)?

RG: The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark. It’s a perfect book, that presents as an idle comedy, but is profound. And somehow under 200 pages, and with a dozen memorable characters, and no central one. It has the tight elegance of the Pythagorean theorem, and I would feel like a metamathemagician if it were mine.

__________________________________

Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch by Rivka Galchen is available now via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.