“When someone you care about gets hurt, make something pretty to look at,” Kenward Elmslie wrote to Lucia Berlin in late September 1995. They were corresponding about their friend, artist and organizer Ivan Suvanjieff, who’d been mugged and injured in Burma and for whom Kenward had made a collage book to cheer him up.

“Two years ago, though it seems further back, I made a collage book for Joe [Brainard], for his first trip to hospital, in Burlington, Vermont,” Kenward wrote Lucia. “So I made a collage book for Ivan. If you go see him, please, pretty please ask to see the book I made for him, OK? A Hurry Job, so it’s not refined, but it does show off my new visual stuff.”

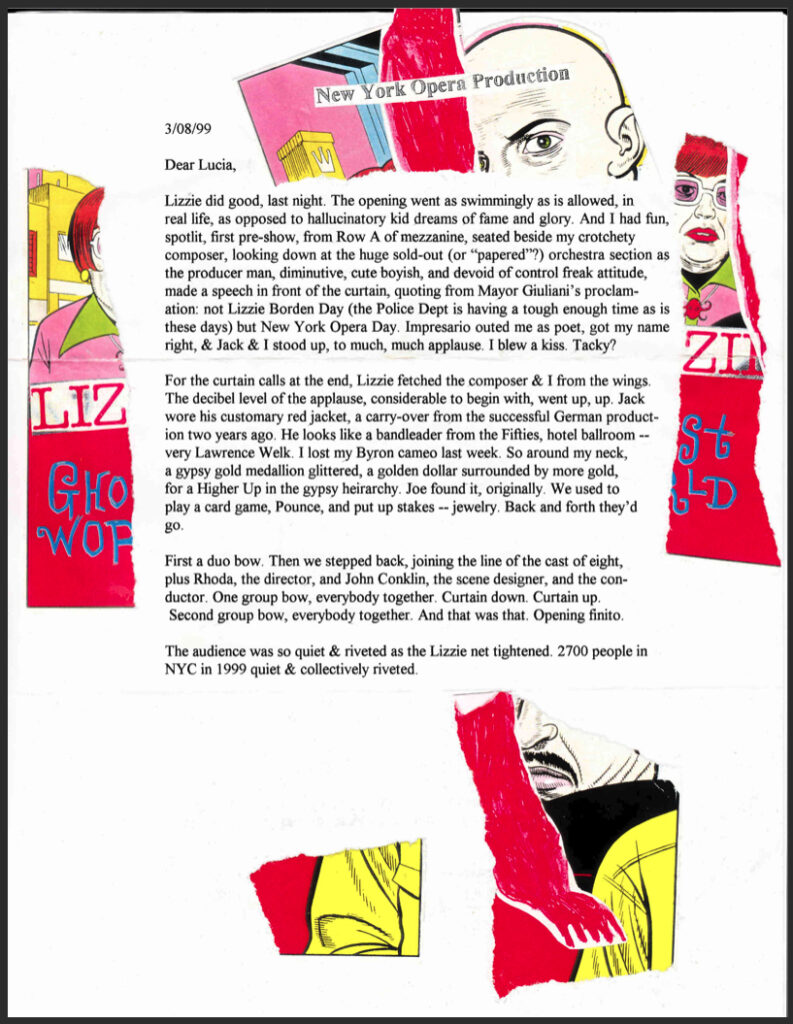

Elmslie—a New York School poet, lyricist, librettist, and collagist—often typed up his frequent letters to Lucia, printed them out, and then decorated the pages with pasted cutouts from magazines or postcards, poetry-reading flyers, and his signature dotted balloon lettering, adding color or “eye-candy” to accompany his weekly (often twice-weekly) reports.

In a March 26, 1999, letter to Kenward, Lucia wrote, “Dearest Kenward, I am honored that you sent me the beautiful, beautiful Lizzie [Borden] collage and poem, & the letter, which should be published as chapbook itself. I have read it over and over.” Lucia is referring to a 25-page letter/collage booklet Kenward made for her detailing the history and current production of his opera, Lizzie Borden.

The libretto he wrote, with music by Jack Beeson, premiered at the New York City Opera on March 25, 1965, but a new New York City Opera production had opened in March 1999 and had been in broadcast on PBS two nights before Lucia wrote the letter. She had watched Lizzie Borden’s “Live from Lincoln Center” transmission at her home in Boulder, Colorado. The Lizzie Borden letter and booklet Kenward made for Lucia included backstage anecdotes, gossip about hostess Beverly Sills’ prerecorded interview with Kenward that aired at intermission, poetry, dialogues, and cut-out, decorated, and drawn illustrations, including one new poem for Lucia in the shape of Lizzie’s axe.

“The poem is lovely, the shape of it exquisite,” Lucia wrote Kenward. “The artwork is delicate and dreamy and catches exactly what I thought most haunting about Lizzie … her lyrical tenderness, as when she protected her sister and especially that incredible scene, with language like leaves falling, sweet sweet, just before she quietly slips into anger. I am so glad to have seen the production and then to read it again.”

Several months later, after Lucia’s story collection, Where I Live Now, was published by Black Sparrow Books, Lucia wrote to Kenward of her worries about its reception. “Thanks again for reading my book and saying nice things. I continue to get very negative responses, now I hope it doesn’t get reviewed.” The book went on to receive rave reviews, but knowing Lucia’s fears about the book’s personal disclosures, Kenward turned to his vast postcard collection, assumed personas from across the globe, and showered Lucia with postcards from these imagined readers.

At least a dozen of these fantasy fan postcards from Kenward survive in their archives (along with hundreds of others), including one black-and-white photograph of French actress Anne Ducaux in a tightly curled coif, her lips hand-painted red, with a written message on the back: “Darling Lucia Berlin, Reading your new stories has changed my life. Well, my hair-do. My sausage curls and bangs are so… so… YOU! World-weary – and yet – chic! Kiss-Kiss, Your, Anne.”

In another postcard, fronted with an image of a forest ranger’s tower near Lynchburg, Virginia, Kenward took the guise of ranger Bob Eberhart-Jones and wrote, “Dear Loosha, I hope there are no fires! My nose is buried deep in your great book of stories, stories this ranger can identify with… They’re so ‘rangy’! Best, Bob Eberhart-Jones.” On the back of a postcard featuring the “world’s largest vase,” in the persona of Zinnia-Mae Everjohn, Kenward penned, “Dear Loosha, A mean witch has put your book inside the world’s largest vase. I’m dying to smash it! I want so bad to read you! What to do! XXX.”

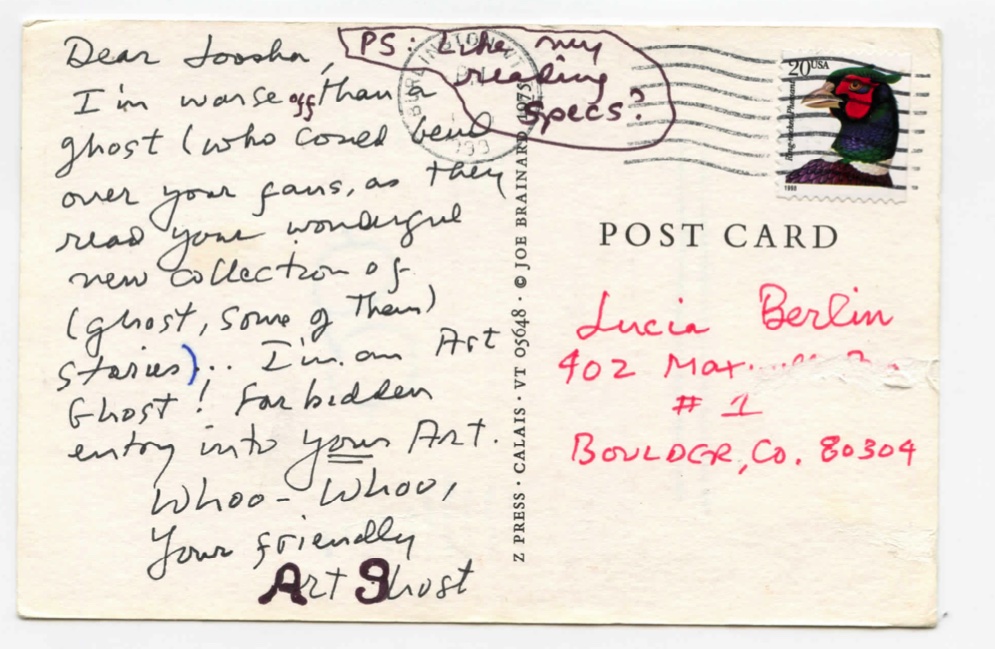

Another postcard features one of Kenward’s own designs, with “Hi Loosha” penned across the front in Kenward’s typical balloon lettering. On the back it reads, “Dear Loosha, I’m worse off than a ghost (who could bend over your fans as they read your wonderful collection of — ghost, some of them — stories)… I’m an Art Ghost! Forbidden entry into your Art. Whoo-Whoo, Your friendly Art Ghost. PS: Like my reading specs?”

These postcards, delivered from June to August 1999, meant a lot to Lucia; I know this because I was her student at the time and she excitedly showed them to me (along with some of her other writing students and friends).

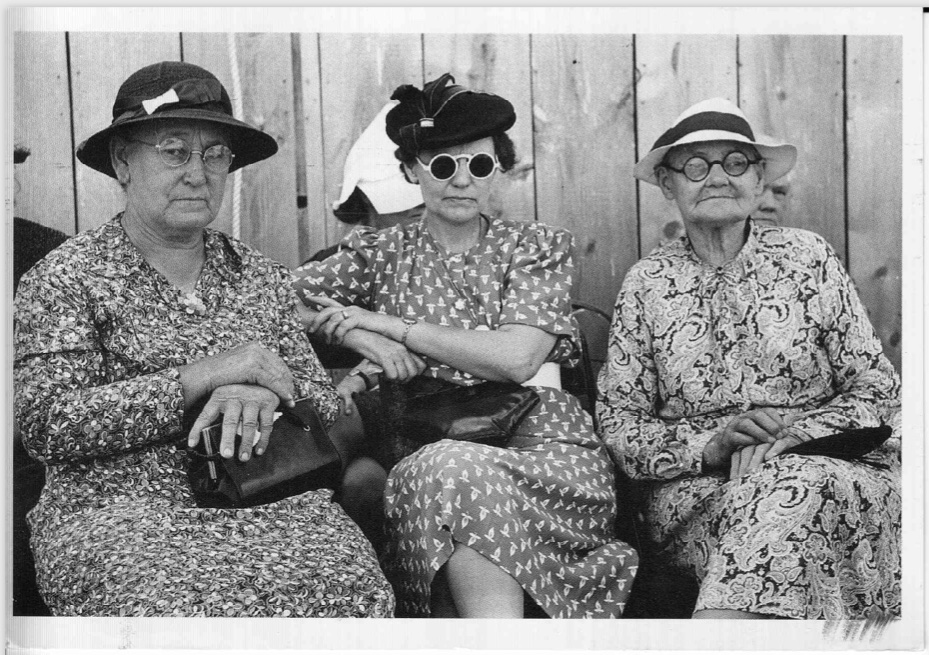

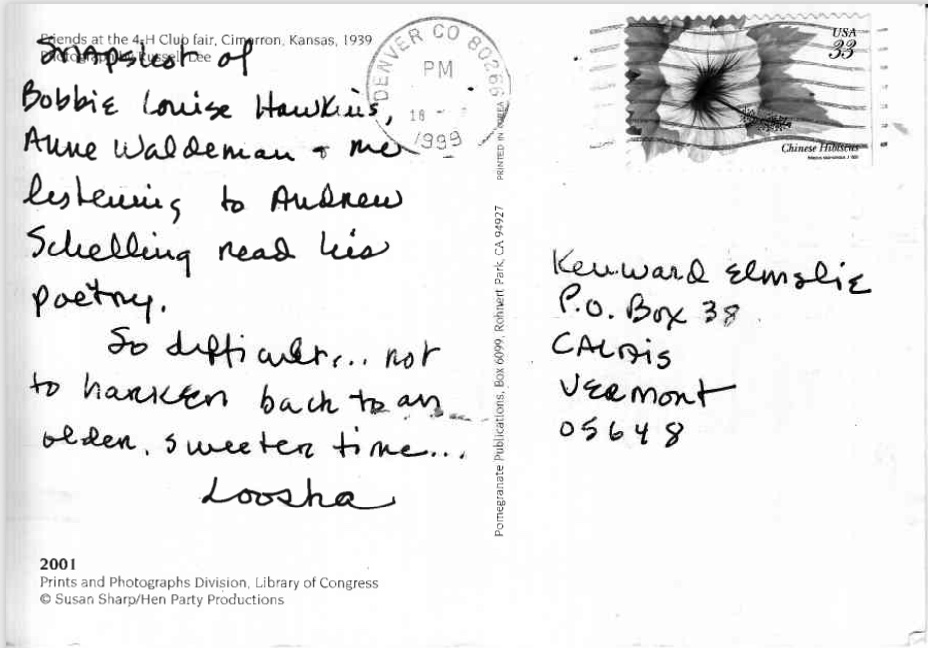

While not quite as avid a postcard collector or collagist as Kenward, Lucia did her best to keep up, sending him unusual postcards with anecdotes inspired from their images. In a 1999 postcard she sent Kenward that featured a 1939 photo of three women at a 4-H Club, Lucia wrote on the back: “Snapshot of Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Anne Waldman & me listening to Andrew Schelling read his poetry. So difficult… not to harken back to an older, sweeter time …. Loosha.”

In another 1999 postcard of an Algerian man wrapped in sackcloth and wearing a straw hat, Lucia wrote, “As my mother always said — The accessories are what make or break the outfit… Or in the words of Elaine Equi, early poem, ‘Even if I didn’t make it my shoes would.’ I haven’t a thing to wear for my reading at Naropa Friday. Agony of indecision… Casual chic? Ethnic… calm & clatter… Scarves? Basic Black? I’m losing my grip. Loosha.” This postcard provoked a response from Kenward, a paper-doll cutout outfit of a “back-to-school outfit for Loosha” that he included in his next letter.

In 2002, a few years after I’d graduated, Lucia suggested that I move to New York City to work as Kenward’s personal assistant, and after flying from Colorado for an interview, I moved into his four-story townhouse on Greenwich Avenue, a home filled with his art and postcard and collage collections. For two more years, I had the honor and duty of delivering letters and postcards from Lucia to Kenward as they arrived to his mailbox, and also the task of photocopying Kenward’s collaged letters and postcards to Lucia, before sealing and stamping the envelopes (also often decorated) to mail them to her.

I continued working for Kenward until the end of 2011, and during that decade, I received my own collaged gifts and letters and poems and postcards from him. For my birthday in 2003, Kenward made me a 30-page tiny booklet, “B-Day July One Liner,” that featured one word cut out and pasted to each 1-by-3-inch page; together they read out a personalized birthday poem for me. Kenward also sent Lucia birthday (and other occasional) greetings, which arrived in a series of numbered postcards mailed separately but which together combined to spell out a message.

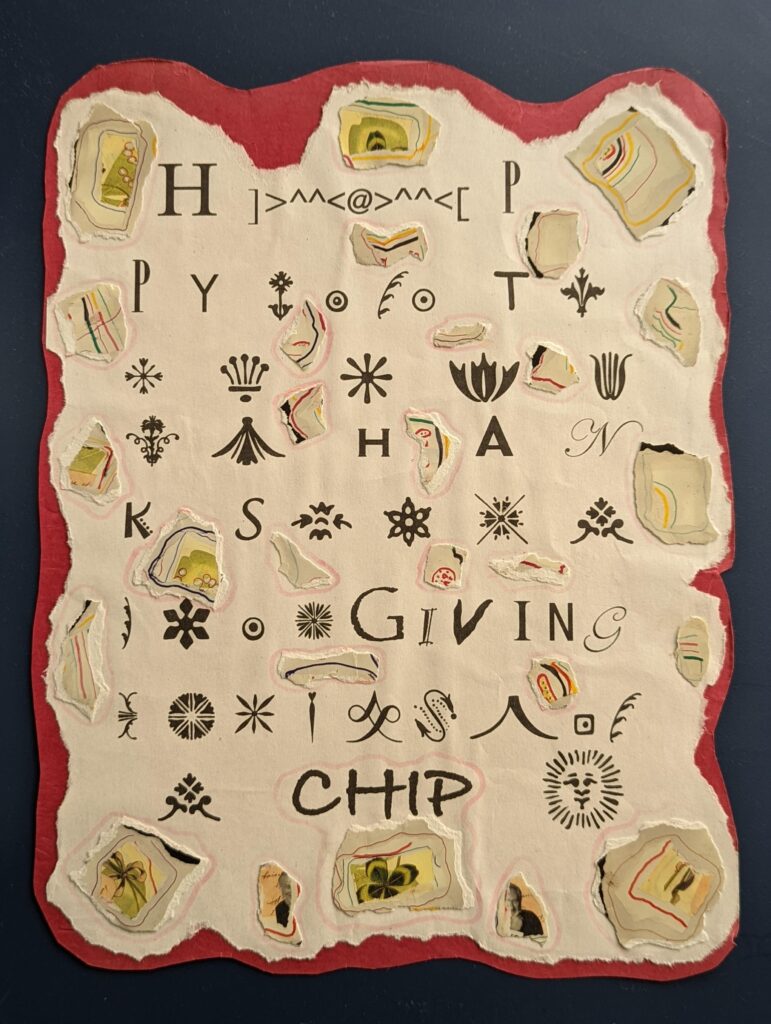

For my first anniversary of my working for Kenward, he presented me with a print and collage cutout—some of the material in the collage cut from his own designed postcards—as a Happy Thanksgiving message. Receiving these visual and playful linguistic treasures from Kenward made me feel like Lucia must have felt on the other end of his generous correspondence. Kenward showed people he cared about them by sharing his wit and keen eye for collecting in these surprising treasures of personalized postcards, poems, and collages.

Kenward enjoyed making visual poems and pieces for friends. He even decorated postcards from his collection into place settings for his dinner guests. For his dinner place cards, Kenward often repurposed collages from “Night Soil,” a set of his 41 color postcards published by Granary Books in 2000. Other times he pulled from his postcard collection, as he did for the hundreds of postcards he exchanged with Lucia over their ten-year correspondence. Kenward also used images and phrases from his boxes and boxes of collected postcards as prompts for poems or for poetic personalized mementos.

Many of the letters and postcards Lucia and Kenward illustrated (and amended, because they often printed out their computer-composed letters and then corrected or added information by pen to the pages) are included in the published volume of their correspondence, Love, Loosha. Many more of their letters and postcards are now housed in Lucia’s and Kenward’s respective archives at Harvard University and the University of California, San Diego. I have my own treasure of the letters and postcards they each sent to me, and one or two is usually displayed on my desk or bookcase in memorial and inspiration.

Like Kenward wrote to Lucia in 1995, “When someone you care about gets hurt, make something pretty to look at.” At the end of this last summer, I was hurting, missing both Lucia and Kenward as I completed copyedits for Love, Loosha, making last-minute additions to include Kenward’s death on June 29, 2022. Kenward’s passing hit me much harder than I expected, though at 93 years old, Kenward had earned his final rest. But it hurt me to know I’d never see Kenward in person again, and it hurt me to know he’d never hold a copy of his and Lucia’s published letters, never look over the book as a book, see one of his postcard collages for Lucia on the book’s cover. I’d hoped to visit Kenward in New York when Love, Loosha was published to personally hand him a copy.

At the end of July, I moved to a new apartment in Montevideo, which meant going through my own collections of memorabilia as I packed up and unpacked them. Among the papers and folders I combed through, I came across many things I’d forgotten, including an envelope with Kenward’s signature balloon lettering and handwriting. “For Chip Bye-Bye Eye Candy, Love, Kenward.” Inside the worn envelope were seven postcards selected for me from his collection: a black-and-white photo with the model’s clothing embroidered in silk thread, several postcards of handsome men, sailor suits, and even a postcard Kenward had received from his longtime partner, the artist/poet Joe Brainard.

It had been years since I’d opened this envelope. Of course, these images and postcards evoked many more memories of the decade I’d spent with Kenward and his collections, and they’d been stored with snapshots of the two of us—one where we’re dressed up for a Pulitzer Prize luncheon and another one we’re sitting on a bench at Vermont’s Gay Pride Parade. My grief is tempered by my gratitude; I have more than my memories of Kenward and Lucia. I have their postcards. I have Kenward’s personalized poems and collages. I have “something pretty to look at.”

__________________________________

Love, Loosha: The Letters of Lucia Berlin and Kenward Elmslie, edited by Chip Livingston, is available via High Road Books/University of New Mexico Press.