On the Groundbreaking Art of Bascove’s Book Covers

From J.M. Coetzee to Alice Walker, a Book Designer Who Took Risks

Seldom do book jacket artists become household names, even in literary households, but there are a few whose work presents such a strong visual identity, readers and bibliophiles can pick them out—even seek them out, in the case of collectors.

Anne Bascove, known just as Bascove, is one of those artists, a master printmaker, illustrator, and painter who has designed dust jackets for Alice Walker, Robertson Davies, Jerome Charyn, T.C. Boyle, J.M. Coetzee, and others.

“She rode the crest of a wave that infused symbolic and metaphoric representation into American illustration,” writes Steven Heller, a former art director at the New York Times. “In fact, she embodied a broader rejection of conventional literalism and romanticism that held sway for decades in book marketing; she transcended commercial norms, imposed new tropes and appealed to readers that had learned to—to rephrase the old truism—tell a book by her covers.”

Many of those iconic covers are on view in Bascove: The Time We Spend With Words at the Norman Rockwell Museum (NRM) in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, through June 5. Deriving from the museum’s 2017 acquisition of 500 of Bascove’s original drawings, prints, paintings, and printing blocks, the exhibition showcases 75 items that reveal her signature style.

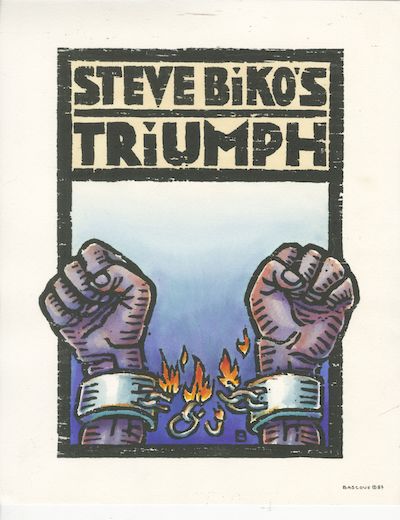

Illustration for “Steve Biko’s Triumph” by Karen Stabiner, Premiere Magazine, November 1987 (ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper). Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRM.2017.03.380, © Bascove. All rights reserved.

Illustration for “Steve Biko’s Triumph” by Karen Stabiner, Premiere Magazine, November 1987 (ink, watercolor, and colored pencil on paper). Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRM.2017.03.380, © Bascove. All rights reserved.

The show opens with Alice Walker’s books: a 1976 edition of her poems, Once; a novel, Meridien, published the same year; and a 1977 edition of the novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland. For all three, Bascove employed woodcuts and watercolor, achieving a bold look full of thick, dark lines and blocky lettering, brightened by spots of refreshing color. Woodcuts are “ridiculous” and “time-consuming,” she said during a March 12 virtual conversation hosted by the museum, but, “I loved doing woodcuts, so that’s what I did. You can’t get that line any other way than carving it out with a knife.”

Those early commissions were hard won. Though she had attended Philadelphia College of Art and trained to be an illustrator, a glass ceiling slowed her trajectory. “There were not that many women in the business,” she says in a video interview playing in the exhibition gallery. “Women illustrators, the few that there were, were doing fashion and children’s bookwork, and then you could do women’s magazines.”

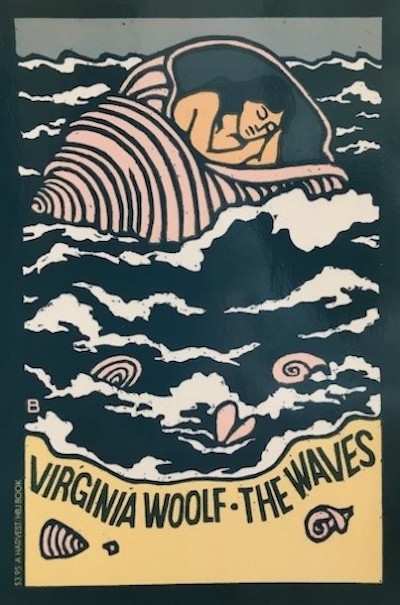

Soon, authors were requesting Bascove for their books. “I found a place for myself doing literature, which was extraordinary because I love reading.”She did that kind of work, too, landing her first assignments at Redbook and then the New York Times as she chipped away at publishing house art directors. In the late 1970s, she produced book jacket art for Harcourt editions of Georges Simenon’s Maigret books, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, and Luisa Valenzuela’s Strange Things Happen Here, among others. She didn’t always work in woodcut, opting for gouache, marker, and colored pencil, depending on the project, but she continued to focus on expression, on faces and bodies, sometimes with a surreal edge.

Cover illustration for The Waves by Virginia Wolff, 1995 (ink on paper). Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRM.2017.03.256 © Bascove. All rights reserved.

Cover illustration for The Waves by Virginia Wolff, 1995 (ink on paper). Norman Rockwell Museum Collection, NRM.2017.03.256 © Bascove. All rights reserved.

Soon, authors were requesting her for their books. “I found a place for myself doing literature, which was extraordinary because I love reading,” she said.

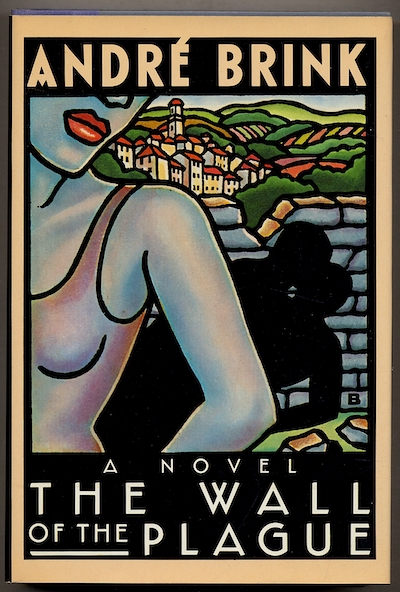

Bascove seemed a particular favorite for South African literature. On view at the NRM: three versions of her artwork for a 1987 reprint of Alan Paton’s 1948 novel, Cry, the Beloved Country, and three for André Brink’s The Wall of the Plague, from 1984. She talked about the latter during the March 12 event, recalling that she encountered pushback from publishing executives about the prominent appearance of Black people on book jackets, even when the main character, as in The Wall, is Black. “So I made her blue, and that got through … I tried my best to work within this system,” she said.

Cover illustration for The Wall of the Plague by Andre Brink, 1985 (ink on paper).

Cover illustration for The Wall of the Plague by Andre Brink, 1985 (ink on paper).

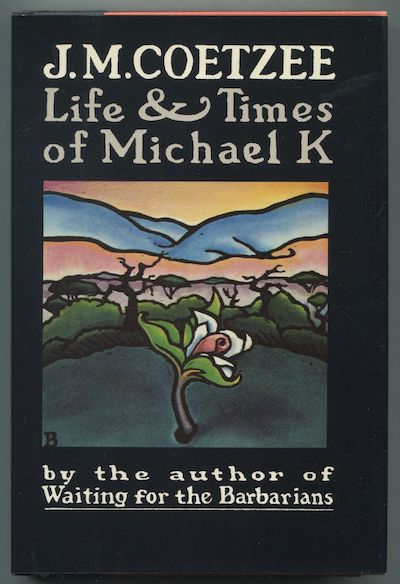

Her commission for Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People was killed for this reason, Bascove said. Her work on J.M. Coetzee’s novels also illustrates this point. The art she created in the early 80s for his Waiting for the Barbarians, depicting a white man washing the detached feet of a person of color, got the book banned in the South. When she produced an ink, watercolor, and colored pencil illustration for Coetzee’s Life & Times of Michael K featuring the main character, a Black South African who undertakes a long journey during apartheid, she was sent back to the drawing board and advised to avoid another controversy. One of the highlights of the NRM exhibition is the ability to see her initial concept for Michael K next to the one finally approved.

Cover illustration for Life and Times of Michael K by JM Coetzee, 1984 (ink on paper).

Cover illustration for Life and Times of Michael K by JM Coetzee, 1984 (ink on paper).

In part, she credits Norman Rockwell for pointing the way toward social justice in art, referencing his 1964 painting, The Problem We All Live With, as an inspiration. She also noticed how “everybody was white” in TV programs and magazines when she was growing up, something she felt she had an opportunity to change. “I’ve always tried to be inclusive even before I knew what inclusive was,” she said.

That ties into Bascove’s overall design philosophy when working on book jacket art. “When you’re working on a job, which is what illustration is, you’re trying to visualize what somebody else has thought and written,” she said. “You really want to be honest and loyal to what that writer has put in that book.”

The artist’s self-described obsession with books carried over into her fine art, some of which is included in the exhibition. In one of her collage pieces, Emily Wore White, she references Emily Dickinson and uses lace, thread, and needles to consider the idea of creativity, particularly for women.

Another collage, The Time We Spend With Words, from which the exhibit takes its name, remixes dictionary pages, photography, drawing, stencils, and microchips. Several of her oil paintings also feature readers and libraries, and in 2001, she published a book of her literary paintings, Where Books Fall Open: A Reader’s Anthology of Wit & Passion.

But her work with authors has always been special, each manuscript “like a gift,” she said. “I am intrigued by stories of wit or mystery, but especially of societies confronting dehumanizing situations, told through the unflinching voices of those who dare to write about what is happening around them. My objective is always to create, with the greatest respect, an image that interprets their words.”