On the “Future Shock” of David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs

Taking Sci-Fi Inspiration from Nineteen Eighty-Four and Metropolis

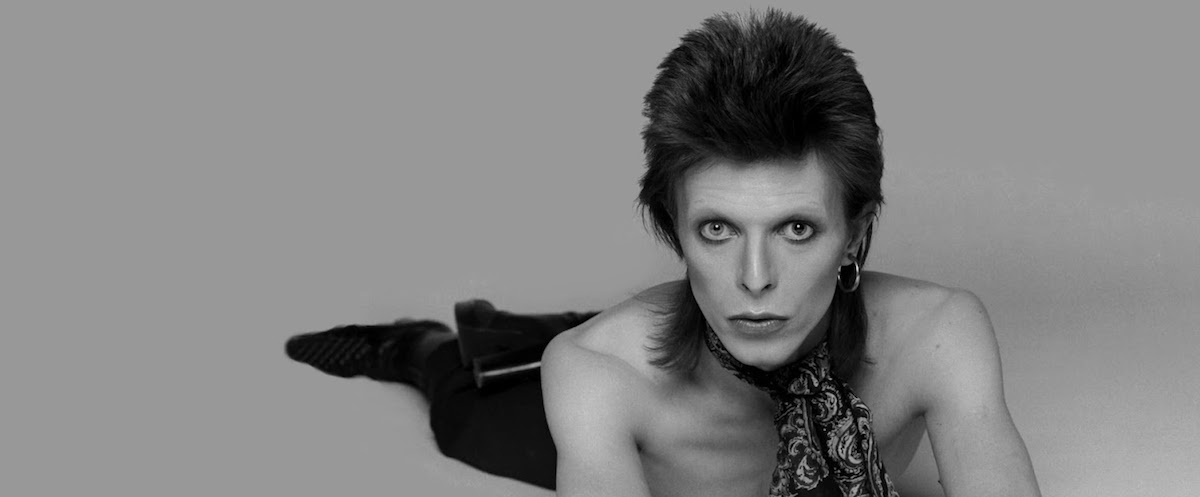

David Bowie darted around his conjoined hotel suites at the venerable Pierre in Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Instead of a guitar, he wielded scissors and glue. Movie cameras and video editing equipment were strewn throughout his rooms. He’d been in New York just a few days; he’d trekked up from Philadelphia, where he’d been recording his upcoming album Young Americans. The plan was to finish working on Young Americans at the famed Record Plant studio in New York. On this night, however, Bowie wasn’t obsessing over his current album-in-progress or even entertaining his habitual retinue of groupies. With images from his most recent record, Diamond Dogs, dancing through his mind, he was building a model.

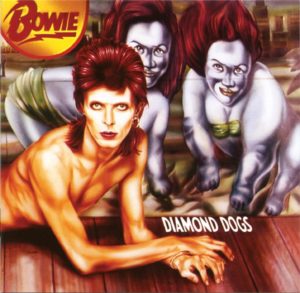

Diamond Dogs came out in May of 1974, and its vision of a post-apocalyptic urban hellscape had come to consume him. In New York, he was surrounded by skyrocketing crime and urban decay. A nationwide recession deepened in the wake of 1973’s stock market crash. The oil crisis was fueling global unrest and fears of long-term energy scarcity. Richard Nixon’s resignation in August laid bare the fragility of democracy. Diamond Dogs resonated.

Bowie wanted to turn the album into a movie. In an interview years later, he recalled that he wanted it set in a world ravaged by fuel shortages and populated by cyborgs. He knew he needed a treatment of some kind to show Hollywood producers, but rather than typing up a simple synopsis, he rented camera equipment and hired a film crew to come to his suites at the Pierre. There they would capture on celluloid a half-hour teaser for the big-screen adaptation of Diamond Dogs, as Bowie envisioned it.

The model he was building for the teaser was of a city. It was called “Hunger City,” a crumbling metropolis rife with social and economic collapse where—according to “Future Legend,” the album’s ominous opening track—“corpses lay rotting on the slimy thoroughfare.” From the tops of skyscrapers, “red mutant eyes gaze down” on the city’s scavenging tribes of barely human survivors. Melody Maker called the song “doom through science fiction.”

In his hotel room, Bowie hung a piece of black fabric. When his model of Hunger City was finished, he installed it in front of that canvas, evoking an aura of eternal night. Then, as his producer Tony Visconti remembered, “He videoed his set for 30 minutes against a black cloth backdrop. Afterwards he played back the tape and he walked against the black cloth background and narrated his story treatment. We combined the prerecorded tape and live David, many times reduced, onto a second machine via the console, and it appeared as if he was actually in the city . . . The Lilliputian-sized David was at the right scale for the set, and it all looked very convincing.”

Visconti never saw the film again, and it’s never surfaced since. One can only imagine the stupefying strangeness of a low-budget short starring a miniaturized David Bowie strolling through his own handmade model of the dystopian Hunger City, sterile skyscrapers looming and red mutant eyes gazing down.

“Diamond Dogs’ debt to Nineteen Eighty-Four makes perfect sense. The album began as an adaptation of the book.”

Then again, the Diamond Dogs album itself is all that’s needed. Grim and oppressive, it was Bowie’s return to science fiction after the success of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. With his Ziggy persona retired, he found himself drawn to a different strain of sci-fi. Visconti, who contributed to the production of Diamond Dogs, called it a work of “future shock,” using the Alvin Toffler titular term that the Los Angeles Times had also deployed while reviewing Bowie’s historic Santa Monica concert in 1972. Indeed, the album brought the cosmic speculation of “Space Oddity” and Rise and Fall plummeting horrifically back down to Earth’s own tomorrow. Bowie had explored terrestrial sci-fi before, most notably in 1967’s “We Are Hungry Men,” whose spoken-word intro presaged Bowie’s eerie opening monologue in Diamond Dogs’ “Future Legend.”

Bowie was reaching beyond his own penchant for future shock. More blatantly than he ever had or ever would again, he cited specific works of science fiction in his music—especially one of his favorite books, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, just as he’d promised William S. Burroughs, in a way, when he’d boasted during their conversation for Rolling Stone in 1973, “Now I’m doing Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four on television.” Where Bowie’s 1970 dystopian song “Saviour Machine” featured the Big Brother–like President Joe, Diamond Dogs contained numerous direct references to literature’s most enduring work of dystopian fiction. The song “We Are the Dead” is a line from the novel, something the book’s protagonist Winston says to his lover, Julia, as the Thought Police come to arrest Winston for his crimes against the state. Bowie sang, “I hear them on the stairs”; Orwell wrote, “There was a stampede of boots up the stairs.” Even more explicit are the songs that immediately follow, “1984” and “Big Brother.” In the latter song, Bowie appears to call back to “Saviour Machine” with the lines “Please, savior, savior, show us.” He also squeezes in a little lingering Ziggy-esque space imagery, as if to purge it from his system: “Give me pulsars unreal.” It was a line that could have served as the title of a sci-fi manifesto.

Diamond Dogs’ debt to Nineteen Eighty-Four makes perfect sense. The album began as an adaptation of the book. Bowie first pictured it as a combination stage production, feature film, and concept album that retold Orwell’s cautionary tale about tyranny and conformity. He dove into the ambitious multi-media project, but he soon ran into a unbeatable opponent: Sonia Orwell, the author’s widow and executor of his literary estate. Unhappy with prior adaptations of her late husband’s work, she refused to grant Bowie permission to adapt his book. As Bowie remarked, “I found out that if I dared touch [Nineteen Eighty-Four], Mrs. George Orwell would sue or something. So I suddenly had to change about in midstream, in the middle of recording.”

That change encompassed a complete overhaul of the story line, including grafting remnants of his Orwell adaptation to an entirely original setting: his mutant-infested Hunger City tableau. It made for a patchy, uneven narrative—there’s even less of a coherent tale to Diamond Dogs as there is to Rise and Fall—but it also gave Bowie poetic license to completely reframe the aftermath of the apocalyptic. The triptych of “We Are the Dead,” “1984,” and “Big Brother” was grandfathered in from the original adaptation plan; it’s entirely possible that part of Bowie’s reason for including these openly Orwell-quoting songs was simply out of spite.

As he explained years later, still fuming, “At the end of 1973 George Orwell’s widow, Sonia, withheld permission for the Nineteen Eighty-Four project. Mrs. Orwell refused to let us have the rights, point blank. For a person who married a socialist with communist leanings, she was the biggest upper-class snob I’ve ever met in my life. ‘Good heavens, put it to music?’ It really was like that.” In some quarters, the prejudice against pop music being a valid vehicle for serious science fiction held.

Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn’t the only work of sci-fi that went into the seething, murky stew of Diamond Dogs. Bowie seemed happy to point them out; they were, after all, works he’d been championing for years just combined in a different way. “I had in my mind this kind of half [Burroughs’s] Wild Boys and Nineteen Eighty-Four world,” he said. “There were these ragamuffins, but they were a bit more violent than ragamuffins. I guess they staggered through from A Clockwork Orange too.” He went so far as to cast himself as one of those ragamuffins, “a real cool cat who lives on top of Manhattan Chase” named Halloween Jack who is mentioned in Diamond Dogs’ title track and whose decadent, shock-haired, eye-patched visage could have belonged to an alternate-reality version of Ziggy Stardust. For that matter, both of them could just as easily have been hitherto unknown incarnations of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion, alongside Elric of Melniboné and Jerry Cornelius.

“Visconti used an array of new digital effects technology on the recording, including the space-age sounds of noise gates, flangers, and phasers—equipment that would later become commonplace but still seemed startlingly futuristic in 1974.”

Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi classic, loomed large over the project as well. The pioneering silent film takes place in a futuristic city where severe class divisions give rise to revolution and one of cinema’s first and most compelling robots indelibly brands the screen. Bowie claimed it was just as important as Orwell’s work in his conception of the album, stating, “I know the impetus for Diamond Dogs was both Metropolis and Nineteen Eighty-Four—those were the two things that went into it.” On the resulting tour to support Diamond Dogs, he indicated that Metropolis’s stark illusion of tomorrow should be an element of the set. The set also contained a hydraulic arm that hoisted Bowie 70 feet above the stage for his nightly rendition of “Space Oddity.” The man who created the astronaut Major Tom, however, was afraid of heights and had to conquer his phobia in order to perform. During one show, the hydraulic arm malfunctioned, leaving Bowie hovering perilously over the audience for six songs—much the same way Major Tom had become stranded in space.

Since the days of “Space Oddity,” Bowie had been as interested in sonically representing science fiction as he was in lyrically representing it. He took that a step further on Diamond Dogs. Visconti used an array of new digital effects technology on the recording, including the space-age sounds of noise gates, flangers, and phasers—equipment that would later become commonplace but still seemed startlingly futuristic in 1974. Most strikingly, the album ends with “Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family,” a song whose coda is a sampled loop of the single syllable “bro” from the word “brother.” Recalled Visconti, “David asked if I could capture the word ‘brother’ at the end of the last track, ‘Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family,’ and repeat it ad infinitum. Of course I could, but lo and behold, that short word was too long for the puny memory banks in the machine. Storage was very limited in those days. So I managed to capture just ‘bro’ with a snare drum hit, and that actually sounded amazing, like a robot with AI that was not working very well singing it.”

It all added up to an alarming, end-times soundtrack that Bowie himself regarded as “desperate, almost panicked.” Looking back, he called Diamond Dogs a “very English, apocalyptic kind of view of our city life” with “obvious inspirations from the Orwellian holocaust trip. It was pretty despondent.” In 2016, bestselling speculative author Neil Gaiman was asked to pick a favorite Bowie album. He chose Diamond Dogs

. . . because it was kind of mine. It was science fiction, it came out when I was 13-and-a-half, and it was a weird mash-up of this strange, dystopian, mutant-y Nineteen Eighty-Four. It filled my head. I loved the imagery. I loved trying to work out what it was about . . . Talking to [fellow author] Alan Moore, who’s a little bit older than I am, we both fed on Bowie imagery and absorbed it, and it went into that early melting pot where you believe it, you take it in, and you let it grow.

If Bowie had known how much his sci-fi music—which was directly inspired by his favorite authors—would go on to inspire future sci-fi authors, he might have thought differently about his next stop. Young Americans, the album he was working on while building his Hunger City model in the Pierre in December of 1974, had nothing to do with science fiction. Newly immersed in contemporaneous R&B, it’s the point at which Bowie resurrected himself as a soul singer—and in 1974, nothing screamed sci-fi less than soul music, at least compared to the likes of glam. Yet on Diamond Dogs, Bowie forged an intriguing fusion of funk and sci-fi; the song “1984” mixes Orwell’s nightmare with music clearly influenced by Isaac Hayes’s 1971 blaxploitation anthem “Theme from Shaft.” But he abandoned this fleeting experiment in sci-fi funk just as others were about to pick up that idea and run with it—and in the process rival Bowie as the decade’s preeminent practitioners of science fiction in popular music.

Bowie wasn’t done with sci-fi, though, and definitely not permanently. He may have abandoned his plans to turn Diamond Dogs into a movie—despite his elaborate efforts in filming a treatment for it—but he was prescient about one thing: his next big sci-fi project was going to be cinematic.

__________________________________

From Strange Stars. Used with permission of Melville House. Copyright © 2018 by Jason Heller.