On the Eve of WWII:

Three Days Before the Bombing of Paris

Françoise Frenkel Experiences the Evacuation of France

In France, nobody believed war was approaching. I breathed in the air of the capital. Very swiftly, I allowed myself to be won over by the general feeling of confidence. I found myself hopeful of an imminent departure and of being reunited with my family.

Throughout these days of heightened crisis, Paris retained its usual outward appearance: movement, color, vitality.

People were discussing the situation on the café terraces, on street corners. In the metro, they would read their neighbor’s newspaper over their shoulder; the need to communicate and, if possible, to discover any fresh details from somebody who was perhaps better informed, spurred people to speak to anybody they encountered, to stop in the street to listen, to look, to discuss matters endlessly.

The general public would wait outside the printers’ to buy the papers, ink still wet from the presses. The crowd would jostle to snatch up any new issue; news vendors on their bicycles seemed to sprout wings as they flew down the street. People queued up in front of the newsstands well before the arrival of the newspaper couriers. Some would take several papers, of differing opinion, scour them feverishly on the spot, then pass them on to other readers.

At times the mainstream broadsheets would reassure the population; at other times they encouraged people to prepare for the inevitable.

Radios blared relentlessly in homes, courtyards, squares, offices, restaurants, and cafés. It was impossible to escape their hold. Their rasping tones permeated everywhere, even into theaters, and into the intervals of classical music concerts.

People listened haphazardly to bulletins in any language. A true tower of Babel! Some made certain to wake up in the middle of the night to listen to American broadcasts. It was an obsession! Nervous tension grew to indescribable levels in those days.

Horror made itself at home in everyday life.Utterly consumed by a fervent desire for peace, the French people were hoping. The notorious phrase: Last year, too, we expected the worst and yet everything worked out . . . circulated from mouth to mouth, like the chorus of a popular song.

Which is why, when hostilities broke out, the whole of France was plunged into dark despair.

For me, it was heartrendingly distressing.

Only then did I truly comprehend the distance separating me from my mother. I saw myself remaining far from her and all my loved ones for the duration of the war, that is for an eternity of torment and worry about them.

The German army was advancing, trampling over Poland and taking control. I anxiously followed the enemy’s lightning progress on the map . . .

The wireless relentlessly reported the horrifying details of carnage, battles, bombardment, devastation, and civilian massacres. Bulletins were broadcast at mealtimes and one had to get used to eating, drinking, chewing, swallowing, all the while listening to the bloody and disastrous stories in the news. Horror made itself at home in everyday life.

From one day to the next, Paris had fallen strangely silent. And so began for France that curious military lull, “the Phoney War.”

It was then the press initiated an extensive campaign against what was known as “the Fifth Column,” which had been growing for years. Keen for a diversion, the general public became obsessed with these sensational revelations.

The prefecture of police instituted “extraordinary measures” of a broad-reaching nature, resolving to conduct a census of all foreigners and to review their status.

These measures, drawn up without any forethought, were implemented on the spot. Police stations, hotel management, landlords, concierges, all those who employed foreigners were asked to ensure compliance with the new regulations.

The whole population started to keep an eye out for “suspects.” Overnight, thousands of foreigners took up position in front of the prefecture of police, forming a line that stretched past the Quai aux Fleurs and reached all the way to Boulevard Saint-Michel.

They would start lining up from dawn; they would bring a folding stool, a little food, a book, newspapers, and they would wait, first in the rains of September and October, then through the snow of November and December.

Separated from their countries of origin by the war, with no possibility of return, some without any money or assistance, these people waited, weary and numb. A terrible despondency reigned over this disparate crowd of uprooted souls.

With most able-bodied men having been called up under the general mobilization, the prefecture of police was staffed almost entirely by young women. They were completely unprepared for this enormous task and were quickly overwhelmed.

Armed with my folding stool, I queued for hours on end in order to obtain my residence permit to allow me to remain in France.

It was physically and mentally exhausting. On the inside I was fretting and fuming, but I valiantly endured the official police requirements. All foreigners, regardless of nationality or race, were required to undertake these lengthy formalities, implemented somewhat haphazardly. There was no intent to harass; it was merely a symptom of the general state of disarray.

Thus I waited patiently, some days coughing, and others even suffering a fever.

No matter! It was Paris, Paris with its afternoons spent along the banks of the Seine, next to the bouquinistes’ stalls, which seemed to have filled with new treasures since my last visit.

There was widespread uncertainty. The press and radio lavished us with advice and instructions.The publishers were remarkably generous toward me. They congratulated me and pledged their support for a new bookshop. The cultural attaché, who had, in turn, arrived back in Paris, had these very encouraging words for me. “You should be credited for remaining at your post until the very last minute.” And he added, smiling, “Just like a valiant soldier.”

He was trying hard to lessen the pain of separation from my beloved bookshop, just as before he had been so generous in helping me to defend it in the face of every adversity.

And so commenced for me, under a rainy sky, the infinitely dark days of the new war.

At last I obtained my residence permit. It stipulated that I could enjoy France’s hospitality until the cessation of hostilities.

*

The rhythm of war accelerated at an ever-increasing rate. The Germans breached new borders. The enemy was approaching France. The “Phoney War” was drawing to an end.

However, confident in the strength of the Maginot Line, everybody still considered it impossible that the national border would be crossed.

At that moment, German reconnaissance raids commenced over Paris and its surrounds. Bombs fell on factories in the suburbs.

There was widespread uncertainty. The press and radio lavished us with advice and instructions. The public remained hesitant. Was it better to die in your home or suffocate in a cellar? When the sirens sounded, some remained in their beds, others went down to the cellar, then came back up or stationed themselves in the stairwell. Some ventured onto the front steps of the building “to see what was going on” and to gossip with neighbors.

Air-raid wardens were strict at first; then they relaxed. “At the end of the day, who knows what’s best?” they admitted.

Parisian women took pride in not having been scared and would spend their mornings sharing their experiences on the telephone.

Only when confidence of being able to defend the city fell abruptly, toward the end of May 1940, did people consider abandoning Paris.

The government was advising people to leave; anybody whose presence in the capital was not absolutely necessary should go, and old people should be the first to leave.

Schools closed; the holidays were thus effectively brought forward by two months. Everybody was preparing to leave, and calmly so.

My elderly former professor, who had remained a devoted friend, suggested I follow him to Avignon, where he was heading himself. I remember the two of us sitting there on the terrace of our regular café, La Boule d’Or, on Place Saint-Michel. He was describing to me the delights of the historic town. The Pont d’Avignon, which until then I had known only as the bridge in the song, a memory from the distant past, was to become a reality . . .

The radio was recommending procuring a safe-conduct pass for the journey, so I took myself off to the police station in my neighborhood very early one morning. I was not in the least astonished to find a line of applicants. After the hours I had spent waiting outside the prefecture of police, I was not about to be put off by anything of that nature.

A group of us were led over to a table where some policemen were sitting. We discovered it would be necessary to get hold of either a medical certificate attesting to the need for a stay at the seaside or in the countryside, or a personal invitation from the place where one was planning to go, preferably from a close relative or, even better, from a patient requiring care.

Some went straight from the police station to besiege doctors’ consulting rooms, others discovered relatives of varying degrees of proximity; everybody was just trying to extricate themselves as best they could, and people began to acquire a fresh spirit of innovation to cope with the changing circumstances.

My old friend urgently contacted his godson, who promptly sent me a formal invitation as required.

The appeals to evacuate Paris were growing urgent, but at the same time, safe-conduct passes were increasingly difficult to obtain.The appeals to evacuate Paris were growing urgent, but at the same time, safe-conduct passes were increasingly difficult to obtain. I received mine not a moment too soon.

On the eve of my departure from Paris, I received news of my bookshop from the Swedish Ambassador: the boxes of books and records, as well as the furniture and fittings, had been put into storage, thanks to the Swedish Embassy.

Three months later, I was informed by a contact in Switzerland that it had all just been confiscated by order of the German government on the grounds of my race.

Having learned from experience, and in order to guard against all eventualities, I had the notion of asking publishers for a letter of recommendation before I headed off into the unknown. I was directed to the appropriate office of the President of the Council of Ministers where I obtained a document drafted in the following terms:

Madame F*** has for many years been the committed and intelligent manager of a bookshop devoted exclusively to French literature, a bookshop which she established in Berlin in 1921. She has rendered significant service to France through the distribution of French literature abroad. May she avail herself of every freedom and benefit our nation has to offer, the nation for which she has so tirelessly toiled.

The document was signed by a high-ranking official from the office of the President of the Council.

My luggage, two suitcases in total, was swiftly packed; my great trunk, salvaged from Berlin, was put into storage in Paris.

My old friend generously took up position at the Gare de Lyon and, after several hours of waiting, obtained two tickets for Avignon.

Finding a car at that time was a challenge; I stationed myself on the side of the footpath in plenty of time, my two suitcases in front of me, in the hope of snaring a taxi. A good hour later, a driver stopped.

*

It was a glorious spring day.

I crossed the city from west to east; the whole Right Bank unfolded before me in a melancholy display, its magnificent perspectives seeming to disappear into infinity.

Paris appeared more beautiful than ever in her imposing grandeur, and as the city passed by I said a painful farewell.

What a fright I had when the driver slowed down a little at Place de la Bastille. An extremely elegant young woman leapt onto the running board of my vehicle and, clinging to the door, said with a charming smile, as if paying a social call, “I hope you don’t mind, madame? It’s just to reserve the car.”

It was so congested in front of the Gare de Lyon that the driver had to set me down at the end of the ramp. I was delighted when a drunkard improvising as a porter offered me his services. Indeed, he acquitted himself of the task admirably.

Half an hour later, we were on our way.

The quiet fields, the peaceful surroundings, the cheerful countryside unfolding outside, it was still as magnificent as ever. We spoke little. We were thinking about those countries already invaded and ravaged, of the dark night ready to descend over France.

Three days later, Paris was bombed. There were a thousand victims.

War had been unleashed on France. The Germans were approaching the capital.

—————————————————

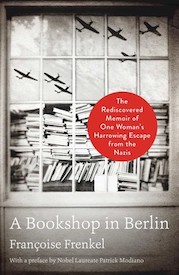

From A Bookshop in Berlin: The Rediscovered Memoir of One Woman’s Harrowing Escape from the Nazis by Françoise Frenkel. Reprinted by permission of Atria, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2019 by Françoise Frenkel.