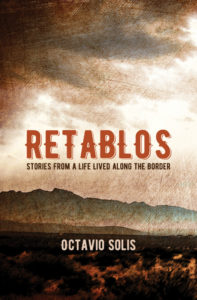

On God, Country, and Being Brown on the US-Mexico Border

Octavio Solis Recounts a Life on the Frontera

ON MY “RETABLOS ”

Memory is its own muse. Every time we recall a specific moment in our past, we remember it differently; we embellish upon it, we turn it into a story or a fable, something that will draw a straighter line between the person we were then and who we are now. Consciously or unconsciously, we trim away the details that seem inconsequential in order to endow the things we remember with greater clarity, with even more weight and significance. And we make connections we weren’t capable of noting before, so that each event in our past is seen in the context of other trials and rites and moments of insight. Sometimes, the spark of a single memory will ignite others, things we hadn’t recalled until now, like suddenly realizing that the room we thought we knew so well has an extra door we never noticed before. Open that door and there’s a new room with its own new store of memories.

This means that every memory has a patina of invention on it. That patina thickens every time we revisit those moments in our past, until they seem more like stories and myths of our formation, more dreamlike and yet more real than what really happened to us. So where is the fact of what actually happened? It’s still there, lost inside of and enhanced by fiction.

When my memories of the actual events of my youth began to feel more like something I’d dreamed, I knew I had to write them down. By committing them to words on paper, I was reclaiming them as my own authentic recollections. But as the act of writing is inherently a fictive one, I found that even the most authentic memory became imbued with the same strange unreality. I wondered if perhaps it wasn’t actually my perspective, but something about the place I’d grown up, Texas, the border, la frontera, that was surreal. Some years ago, a substantial amount of naturally occurring lithium was discovered in El Paso’s drinking water supply. Maybe that’s what gives this otherworldly cast to my memories of the city of my origin, but I suggest it’s more than that. I feel it’s something verging on the divine, though not the divine we are taught to believe in.

That’s why I choose to call these stories retablos. A retablo is a devotional painting, usually laid on a small, thin plate of cheap, repurposed metal, in which a dire event is depicted—an accident, a crime, an illness, a calamity, some terrible rift in a person’s life, which they survive thanks to the intercession of the Divine. They are ex-voto, that is, “from a vow,” commissioned and created as a form of thanks. At once visual and literary, they record the crisis, the divine mediation and the offering of thanks in a single frame, thus forming a kind of flash-fiction account of an electrifying, life-altering event. I imagined the stories of this collection in this same disconnected (and yet thoroughly interconnected) way.

“When my memories of the actual events of my youth began to feel more like something I’d dreamed, I knew I had to write them down.”

I’ve found that every time I read one of the stories, the same thing happens. I change it a little, adding another patina, another layer to the memory. But this is what any writer should do in the interest of storytelling. In the end, they’re only stories. I’m not interested in autobiography. If this is a memoir, it’s a faulty one, because I have given myself leave to invent elements within it. I suppose I am using the poetic voice to convey the authentic. I am more interested in depicting the events of my life as a means to identify and limn the mythology of being brown along the US/Mexico border during a specific period in time, beyond politics, beyond polemics and rhetoric, in order to share those resonances with others who are my age and others who are experiencing similar things right now.

One thing I have learned from writing these retablos: the shit on the border never changes. There will always be those who want to come across, and those who want to keep them where they are. The push and pull, the friction between the tectonic plates that are Mexico and the US will always create mountains of stress, dislocation and upheaval among the people who live there. Maybe this is political, after all, but I think it’s really a condition of our culture: it’s how we live now, it is our particular mythology, replete with gods and monsters, heroes and fallen angels, troubadours and exiles.

In the end, I’m trying to figure myself out. I’m coming to terms with who I am by looking back at what I was. I wrote Retablos to see how that skinny brown kid riding his bike out there in the desert made sense of his complicated, deeply beautiful and troubled world. So that perhaps I might learn to make sense of the one I live in today.

JESUS IN OUR MOUTHS

I win an essay contest when I’m 17. It’s the year of the Bicentennial, and it’s about America and patriotism and God. Two other girls from my school are traveling with me to Brownwood, Texas, to present our essays before large appreciative audiences from all over the state.

It’s a long drive to this place. We go in a rented van, the three of us and our teacher who is in the habit of saying Praise God all the time. In fact, she says it so often, we started saying it too.

We’ll need to stop and get some gas.

Praise God.

The baloney sandwiches are good.

Praise God.

We’ll be there before dark.

Praise the Lord.

That evening in Brownwood, we get a tour of the Douglas MacArthur Academy of Freedom and admire his corncob pipe. American flags everywhere. Then we go to a big ranch house where a huge buffet spread is laid out for us. There must be about 30 people there. And they say Praise God too. After we eat some more sandwiches and mashed potatoes, this man gets up and gives witness, that is, he tells us how he found Jesus and let him into his heart, and then we all stand in a wide circle, hold hands, close our eyes and pray. I hear my teacher leading the prayer, intent and passionate, then someone else’s voice takes up where she leaves off, and so on. My eyes are clamped shut as I try hard to feel the rapture in the room, but I just can’t get into it. I really need to pee.

I’m fairly certain it’s a man holding my left hand because I can feel his big class ring digging into my pinkie, but nestled in my right is a smaller, softer hand. A girl’s hand like a little bird with bird smoothness, warm and tentative. I don’t know who she is, or what she looks like, but it doesn’t matter. We’re two hands randomly clasped together in this circle of faith. I’m not sure if all the overheated praying has anything to do with it, but I sense our pulses quickening. Amen, someone cries. I feel her press against my hand and I send that pressure back as softly as I can. I caress her knuckle with my thumb, slowly at first, imperceptibly, like I’m not even aware of it myself. Then I feel her fingernail drawing circles on the back of my hand. Amen, I hear again. Our palms now moist, fingers caress and lace and chafe against the urges inside. Through her hand I touch every intimate part of her as she whispers oh yes Lord yes Lord oh yes. This goes on for a while obliterating all the prayers in the room and when the last amen of many is uttered, we open our eyes and regard each other for the first time. She’s a pretty Permian Basin girl with large penetrating blue eyes and straw-blonde hair. Pure West Texas loveliness. That’s what I see. What she sees I can’t say. But her neck breaks out in a rash all the way down to her chest.

“I don’t know who she is, or what she looks like, but it doesn’t matter. We’re two hands randomly clasped together in this circle of faith.”

While everyone goes for seconds at the buffet table, I go to the bathroom and then sneak outside to the large sloping backyard. I find a bench in an arbor and quietly sit in the dark and cry. I don’t know why but the sobs just burble up like they’ve been waiting for this time. Then before I know it, the Permian Basin girl is sitting beside me, holding my hand again just as tightly as before, and she’s crying too. I’m ashamed and I say so, but she won’t let me say anything more. We just huddle in that arbor crying and then kiss like crazy fools for a while, digging our tongues deep into each other, finding Jesus in our mouths.

The next morning, we read our essays in this huge auditorium and I put everything I’ve got into mine. It’s all about Love of God and Country and the righteousness of our Christian nation, but I’m feeling none of it. I don’t want to pray and I don’t want to tell America how great she is and I don’t want to be 17 anymore. I want to get back in the van and go home. Not with Jesus in my heart but the ghost pressure of her hand in mine taking me there.

I get a letter from her a few weeks later, a sweet note saying hello and how much she’d like to see me if I come by town again, and how that night with me has made a difference she didn’t expect. I can feel her Permian Basin heart in every word. But all over the letter, in almost every other sentence, she writes Praise God.

__________________________________

From Retablos: Stories From A Life Lived Along The Border. Courtesy of City Lights Publishers. Copyright 2018 by Octavio Solis.

Octavio Solis

Octavio Solis is considered one of the most prominent Latino playwrights in America. His works have been produced in several theatres, including the Center Group Theatre and the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, South Coast Repertory, the Magic Theatre and the California Shakespeare Theatre in the San Francisco Bay Area, Yale Repertory Theatre, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and Dallas Theater Center. Among his many awards and grants, Solis has received an NEA Playwriting Fellowship, the Kennedy Center's Roger L. Stevens award, the TCG/NEA Theatre Artists in Residence Grant, the National Latino Playwriting Award, and the PEN Center USA Award for Drama. His fiction and short plays have appeared in the Louisville Review, Zyzzyva, Chicago Quarterly Review, and Huizache, among others. Retablos, his first book, is available from City Lights.