Life Got You Down? Time to Read The Master and Margarita

Or, How to Be Happy With Russian Literature

‘“And what is your particular field of work?” asked Berlioz. “I specialize in black magic.”’

![]()

If many Russian classics are dark and deep and full of the horrors of the blackness of the human soul (or, indeed, are about the Gulag), then this is the one book to buck the trend. Of all the Russian classics, The Master and Margarita is undoubtedly the most cheering. It’s funny, it’s profound and it has to be read to be believed. In some ways, the book has an odd reputation. It is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest novels of the 20th century and as a masterpiece of magical realism, but it’s very common even for people who are very well read not to have heard of it, although among Russians you have only to mention a cat the size of a pig and apricot juice that makes you hiccup and everyone will know what you are talking about. Most of all, it is the book that saved me when I felt like I had wasted my life. It’s a novel that encourages you not to take yourself too seriously, no matter how bad things have got. The Master and Margarita is a reminder that, ultimately, everything is better if you can inject a note of silliness and of the absurd. Not only is this a possibility at any time; occasionally, it’s an absolute necessity: “You’ve got to laugh. Otherwise you’d cry.”

For those who already know and love The Master and Margarita, there is something of a cult-like “circle of trust” thing going on. I’ve formed friendships with people purely on the strength of the knowledge that they have read and enjoyed this novel. I have a friend who married her husband almost exclusively because he told her he had read it. I would normally say that it’s not a great idea to found a lifelong relationship on the basis of liking one particular book. But, in this case, it’s a very special book. So, if you are unmarried, and you love it and you meet someone else who loves it, you should definitely marry them. It’s the most entertaining and comforting novel. When I was feeling low about not being able to pretend to be Russian any more, I would read bits of it to cheer myself up and remind myself that, whatever the truth about where I come from, I had succeeded in understanding some important things about another culture. It is a book that takes your breath away and makes you laugh out loud, sometimes at its cleverness, sometimes because it’s just so funny and ridiculous. I might have kidded myself that you need to be a bit Russian to understand Tolstoy. But with Bulgakov, all you need to understand him is a sense of humor. His comedy is universal.

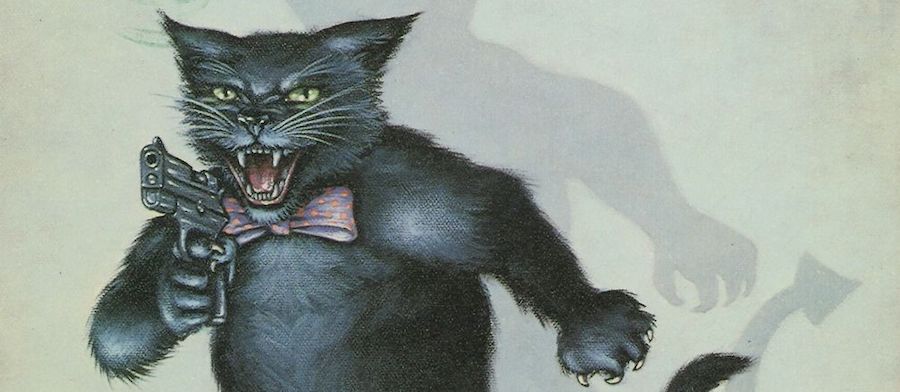

Written in the 1930s but not published until the 1960s, The Master and Margarita is the most breathtakingly original piece of work. Few books can match it for weirdness. The devil, Woland, comes to Moscow with a retinue of terrifying henchmen, including, of course, the giant talking cat (literally “the size of a pig”), a witch and a wall-eyed assassin with one yellow fang. They appear to be targeting Moscow’s literary elite. Woland meets Berlioz, influential magazine editor and chairman of the biggest Soviet writers’ club. (Berlioz has been drinking the hiccup-inducing apricot juice.) Berlioz believes Woland to be some kind of German professor. Woland predicts Berlioz’s death, which almost instantly comes to pass when the editor is decapitated in a freak accident involving a tram and a spillage of sunflower oil. All this happens within the first few pages.

A young poet, Ivan Bezdomny (his surname means “Homeless”), has witnessed this incident and heard Woland telling a bizarre story about Pontius Pilate. (This “Procurator of Judaea” narrative is interspersed between the “Moscow” chapters.) Bezdomny attempts to chase Woland and his gang but ends up in a lunatic asylum, ranting about an evil professor who is obsessed with Pontius Pilate. In the asylum, he meets the Master, a writer who has been locked away for writing a novel about Jesus Christ and, yes, Pontius Pilate. The story of the relationship between Christ and Pilate, witnessed by Woland and recounted by the Master, returns at intervals throughout the novel and, eventually, both stories tie in together. (Stick with me here. Honestly, it’s big fun.)

Meanwhile, outside the asylum, Woland has taken over Berlioz’s flat and is hosting magic shows for Moscow’s elite. He summons the Master’s mistress, Margarita, who has remained loyal to the writer and his work. At a midnight ball hosted by Satan, Woland offers Margarita the chance to become a witch with magical powers. This happens on Good Friday, the day Christ is crucified. (Seriously, all this makes perfect sense when you are reading the book. And it is not remotely confusing. I promise.) At the ball, there is a lot of naked dancing and cavorting (oh, suddenly you’re interested and want to read this book?) and then Margarita starts flying around naked, first across Moscow and then the USSR. Again, I repeat: this all makes sense within the context of the book.

“Literature can be a catalyst for change. But it can also be a safety valve for a release of tension and one that results in paralysis.”Woland grants Margarita one wish. She chooses the most altruistic thing possible, liberating a woman she meets at the ball from eternal suffering. The devil decides not to count this wish and gives her another one. This time, Margarita chooses to free the Master. Woland is not happy about this and gets her and the Master to drink poisoned wine. They come together again in the afterlife, granted “peace” but not “light,” a limbo situation that has caused academics to wrap themselves up in knots for years. Why doesn’t Bulgakov absolve them? Why do both Jesus and the Devil seem to agree on their punishment? Bulgakov seems to suggest that you should always choose freedom—but expect it to come at a price.

One of the great strengths of The Master and Margarita is its lightness of tone. It’s full of cheap (but good) jokes at the expense of the literati, who get their comeuppance for rejecting the Master’s work. (This is a parallel of Bulgakov’s experience; he was held at arm’s length by the Soviet literary establishment and “allowed” to work only in the theatre, and even then with some difficulty). In dealing so frivolously and surreally with the nightmare society in which Woland wreaks havoc, Bulgakov’s satire becomes vicious without even needing to draw blood. His characters are in a sort of living hell, but they never quite lose sight of the fact that entertaining and amusing things are happening around them. However darkly comedic these things might sometimes be.

While The Master and Margarita is a hugely complex novel, with its quasi-religious themes and its biting critique of the Soviet system, above all it’s a big fat lesson in optimism through laughs. If you can’t see the funny side of your predicament, then what is the point of anything? Bulgakov loves to make fun of everyone and everything. “There’s only one way a man can walk round Moscow in his underwear—when he’s being escorted by the police on the way to a police station!” (This is when Ivan Bezdomny appears, half naked, at the writers’ restaurant to tell them a strange character has come to Moscow and murdered their colleague.) “I’d rather be a tram conductor and there’s no job worse than that.” (The giant cat talking rubbish at Satan’s ball.) “The only thing that can save a mortally wounded cat is a drink of paraffin.” (More cat gibberish.)

The final joke of the book is that maybe Satan is not the bad guy after all. While I was trying to recover my sense of humor about being Polish and Jewish instead of being Russian, this was all a great comfort. Life is, in Bulgakov’s eyes, a great cosmic joke. Of course, there’s a political message here, too. But Bulgakov delivers it with such gusto and playfulness that you never feel preached at. You have got to be a seriously good satirist in order to write a novel where the Devil is supposed to represent Stalin and/or Soviet power without making the reader feel you are bludgeoning them over the head with the idea. Bulgakov’s novel is tragic and poignant in many ways, but this feeling sneaks up on you only afterwards. Most of all, Bulgakov is about conjuring up a feeling of fun. Perhaps because of this he’s the cleverest and most subversive of all the writers who were working at this time. It’s almost impossible to believe that he and Pasternak were contemporaries, so different are their novels in style and tone. (Pasternak was born in 1890, Bulgakov in 1891.) The Master and Margarita and Doctor Zhivago feel as if they were written in two different centuries.

Unlike Pasternak, though, Bulgakov never experienced any reaction to his novel during his lifetime, as it wasn’t published until after he had died. One of the things that makes The Master and Margarita so compelling is the circumstances in which it was written. Bulgakov wrote it perhaps not only “for the drawer” (i.e. not to be published within his lifetime) but never to be read by anyone at all. He was writing it at a time of Black Marias (the KGB’s fleet of cars), knocks on the door and disappearances in the middle of the night. Ordinary life had been turned on its head for most Muscovites, and yet they had to find a way to keep on living and pretending that things were normal. Bulgakov draws on this and creates a twilight world where nothing is as it seems and the fantastical, paranormal and downright evil are treated as everyday occurrences.

It’s hard to imagine how Bulgakov would have survived if the novel had been released. Bulgakov must have known this when he was writing it. And he also must have known that it could never be published—which means that he did not hold back and wrote exactly what he wanted, without fear of retribution. (Although there was always the fear that the novel would be discovered. Just to write it would have been a crime, let alone to attempt to have it published.) This doesn’t mean that he in any way lived a carefree life. He worried about being attacked by the authorities. He worried about being prevented from doing any work that would earn him money. He worried about being unable to finish this novel. And he worried incessantly—and justifiably—about his health.

During his lifetime Bulgakov was known for his dystopian stories “The Fatal Eggs” (1924) and “The Heart of a Dog” (1925) and his play The Days of the Turbins (1926), about the civil war. Despite his early success, from his late twenties onwards, Bulgakov seemed to live with an awareness that he was probably going to be cut down in mid-life. He wrote a note to himself on the manuscript of The Master and Margarita: “Finish it before you die.” J.A.E. Curtis’s compelling biography Manuscripts Don’t Burn: Mikhail Bulgakov, A Life in Letters and Diaries, gives a near-cinematic insight into the traumatic double life Bulgakov was leading as he wrote the novel in secrecy. I love this book with the same intensity that I love The Master and Margarita. Curtis’s quotes from the letters and the diaries bring Bulgakov to life and are packed full of black comedy and everyday detail, from Bulgakov begging his brother not to send coffee and socks from Paris because “the duty has gone up considerably” to his wife’s diary entry from New Year’s Day 1937 which tells of Bulgakov’s joy at smashing cups with 1936 written on them.

As well as being terrified that he would never finish The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov was becoming increasingly ill. In 1934, he wrote to a friend that he had been suffering from insomnia, weakness and “finally, which was the filthiest thing I have ever experienced in my life, a fear of solitude, or to be more precise, a fear of being left on my own. It’s so repellent that I would prefer to have a leg cut off.” He was often in physical pain with a kidney disease but was just as tortured psychologically. There was the continual business of seeming to be offered the chance to travel abroad, only for it to be withdrawn. Of course, the authorities had no interest in letting him go, in case he never came back. (Because it would make them look bad if talented writers didn’t want to live in the USSR. And because it was much more fun to keep them in their own country, attempt to get them to write things praising Soviet power and torture them, in most cases literally.)

It is extraordinary that Bulgakov managed to write a novel that is so full of humor and wit and lightness of tone when he was living through this period. He grew accustomed to being in a world where sometimes the phone would ring, he would pick it up and on the other end of the line an anonymous official would say something like: “Go to the Foreign Section of the Executive Committee and fill in a form for yourself and your wife.” He would do this and grow cautiously hopeful. And then, instead of an international passport, he would receive a slip of paper that read: “M.A. Bulgakov is refused permission.” In all the years that Bulgakov continued, secretly, to write The Master and Margarita—as well as making a living (of sorts) as a playwright—what is ultimately surprising is that he did not go completely insane from all the cat-and-mouse games that Stalin and his acolytes played with him. Stalin took a personal interest in him, in the same way he did with Akhmatova. There’s some suggestion that his relationship with Stalin prevented Bulgakov’s arrest and execution. But it also prevented him from being able to work on anything publicly he wanted to work on.

How galling, too, to have no recognition in your own lifetime for your greatest work. When the book did come out in 1966-7, its significance was immense, perhaps greater than any other book published in the 20th century. As the novelist Viktor Pelevin once said, it’s almost impossible to explain to anyone who has not lived through Soviet life exactly what this novel meant to people. “The Master and Margarita didn’t even bother to be anti-Soviet, yet reading this book would make you free instantly. It didn’t liberate you from some particular old ideas, but rather from the hypnotism of the entire order of things.”

The Master and Margarita symbolizes dissidence; it’s a wry acknowledgement that bad things happened that can never, ever be forgiven. But it is also representative of an interesting kind of passivity or non-aggression. It is not a novel that encourages revolution. It is a novel that throws its hands up in horror but does not necessarily know what to do next. Literature can be a catalyst for change. But it can also be a safety valve for a release of tension and one that results in paralysis. I sometimes wonder if The Master and Margarita—the novel I have heard Russians speak the most passionately about—explains many Russians’ indifference to politics and current affairs. They are deeply cynical, for reasons explored fully in this novel. Bulgakov describes a society where nothing is as it seems. People lie routinely. People who do not deserve them receive rewards. You can be declared insane simply for wanting to write fiction. The Master and Margarita is, ultimately, a huge study in cognitive dissonance. It’s about a state of mind where nothing adds up and yet you must act as if it does. Often, the only way to survive in that state is to tune out. And, ideally, make a lot of jokes about how terrible everything is.

Overtly, Bulgakov also wants us to think about good and evil, light and darkness. So as not to be preachy about things, he does this by mixing in absurd humor. Do you choose to be the sort of person who joins Woland’s retinue of weirdos? (Wall-eyed goons, step forward!) Or do you choose to be the sort of person who is prepared to go to an insane asylum for writing poetry? (I didn’t say these were straightforward choices.) On a deeper level, he is asking whether we are okay with standing up for what we believe in, even if the consequences are terrifying. And he is challenging us to live a life where we can look ourselves in the eye and be happy with who we are. There is always a light in the dark. But first, you have to be the right kind of person to be able to see it.

![]()

From The Anna Karenina Fix, by Viv Grokop, courtesy Abrams. Copyright 2018, Viv Groskop.