On a Non-Native English Speaker’s Creative Journey to Authenticity

Dariel Suarez Considers Language is a Vehicle for Culture

As an undergraduate creative writing student, one piece of feedback kept appearing on the margin of my stories: awkward phrasing. Red markings littered my pages, arrows pointing every which way, words circled or crossed out, re-written passages squeezed between lines. As a result, I began to obsess over language. I read contemporary fiction by American-born writers, particularly those known for their stylistic prowess. I pilfered and repurposed any metaphor or descriptive passage I found appealing. I made and frequently updated lists of words to use in my stories. I carried a modern thesaurus and dictionary everywhere and actively avoided the kind of outdated language found in classic literature—you know, the one that had gotten me into writing in the first place.

After three years of this and getting into an MFA program, the feedback remained: your phrasing is awkward. By then, I’d developed a bit of a complex. When asked about my biggest area of weakness, my fixed answer became “language.” It wasn’t a huge confidence boost to admit this. The whole enterprise of being a good writer, it seemed to me, hinged on that very thing: your ability to successfully string just the right words together. I tried camouflaging my insecurities by claiming that conflict and plot were more important. Secretly, though, I felt profound envy for the writers who seemed naturally gifted at wielding evocatively inventive sentences at every turn.

Then, during workshop one night, a professor praised the supposed awkwardness of my style as something worthy of embrace. “Nurture it as your own,” he said after class. Suddenly, I realized what lay at the heart of my struggle. I was aiming to please an audience whose native language and cultural experience were fundamentally different from mine. No matter how much I tried, the result would be artificial, clunky, detached from the reality and sensibility driving my fiction.

I didn’t learn to speak English until I was 15 years old. The authors whose books led me to write were Latin American and Russian. My stories were set in Cuba, where I grew up. In essence, my writing was an act of literal and cultural translation. A new path opened for me the instant I recognized this. I began to incessantly read contemporary works in translation. I rediscovered the sort of global literature that had inspired me to draft my first few stories. I found authors from South Africa, Nigeria, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, China, and Korea who were engaging with place the way I wished to—with uncompromising authenticity. Their style, or that of their translators, would’ve been tagged as awkward in my classes.

Following the completion of my MFA, I committed to two projects: a story collection and a novel, both set in Cuba. My language, I decided, would remain “awkward.” Which, in practice, simply meant I would prioritize the cultural authenticity and idiosyncrasy of my characters over any American reader. Immediately, I experienced a level of freedom and confidence I hadn’t felt before.

At the same time, a new set of obstacles appeared. How could I remain true to a people and culture in a language that wasn’t theirs? What would I do when something was untranslatable? How much Spanish should there be in the writing? To what extent would I be willing to compromise for the sake of clarity or familiarity, especially at key moments in the story? The incessant wrestling with these questions could have a detrimental or even stifling effect if the answers weren’t clear.

Thus, I established a set of craft parameters I use to this day. The first is to use Spanish whenever a word or phrase would be severely undermined by translation. For instance, certain idiosyncratic Cuban expressions just wouldn’t have the same impact in English.

We have to challenge our audience and not just pander to them.

“!Carajo!” “Me cago en diez,” “Tremenda muela,” “Tírame un cabo”: there’s no way to translate these without losing the essence of the original. Therefore, if I choose to include them, instead of offering an immediate translation, I focus on placement and rely on the context and tone of the narrative for the reader to get what’s necessary.

Then there are the cultural references unique to a country or region. Having to constantly explain the context for a detail, setting, or circumstance—especially if it doesn’t deepen or complicate the story—is ultimately a burden for both writer and reader. I find it more effective to weave these types of references into the conflict and stakes.

If their inclusion is indispensable to the arc of the story, readers are more likely to experience them as an earned and authentic element, even if they don’t have the full picture. Being intentional and thorough in this area can also help avoid gratuitous or stereotypical details. The more deeply embedded your socio-cultural references are, the more you force yourself to genuinely engage with them and interrogate their usage.

Finally—though I’m writing in English to a largely American audience—everything happening in my work exists outside that language and country, and my job shouldn’t be catering to them. Instead, I need to honor my characters’ plight, respect the specificity of my characters’ experiences and culture, prod and get at some sort of complex truth in the context of the place they’re inhabiting and the forces they’re facing.

Language is a vehicle, the lens through which my reader can follow along. I have to tend to it, ensure it is effective and compelling. But it is in the authenticity of a story’s central conflict and its layered characters that I want my reader to connect and become invested. In order to achieve this, my language should be a reflection of my characters’ world and sensibilities, even if at times it might seem strange or awkward to someone not familiar with it.

None of the above are hardened rules, of course. If there’s something writers know to dwell in, it’s contradiction. I go through my fair share of concessions when it comes to language. There are enough nuances in every single sentence to render my decision-making process difficult and occasionally inconsistent; I’m not too hard on myself when I have to compromise.

But I’m always interrogating what ends up on the page, asking myself what my characters would think if they saw their own words and thoughts and actions depicted in a different tongue. It is exhausting work, no doubt, writing in-between two languages, the relentless effort of translating. It is also immensely rewarding to complete something which feels authentic and doesn’t water down, exploit, or demean your native home.

Now that I’m a writing instructor, I get asked about avoiding stereotypes and exoticism. I must admit the question frustrates me. If you’re asking, part of me thinks you’ve already failed. Not a generous response, I know, but some of the most critical responsibilities of a writer are to imagine, to dig, to engage, to persistently interrogate. We have to move past the obvious and recognizable. We have to avoid reducing characters and places to a few descriptors or buzzwords presented in a different language. We have to challenge our audience and not just pander to them. The same goes for ourselves.

In my most vulnerable moments, I still question the clarity of my style. I’ll read sentences out loud several times. I worry some readers will be confused by a word choice, even if it’s loyal to its linguistic and cultural source. The longwinded nature of Spanish betrays me more often than I’m willing to admit. But I’ve also grown to embrace the occasional awkwardness of my phrasing, as my professor encouraged me to do. I’ve accepted that my audience, whoever that is, will see it as a sincere attempt to tell an authentic story, no matter how different from their own expectations, experiences, or world view. Ultimately, even if I fully surrendered to an Americanized, more familiar, highly stylized mode of expression in my writing, a satisfying turn of phrase would only take my characters and their complex lives so far.

__________________________________

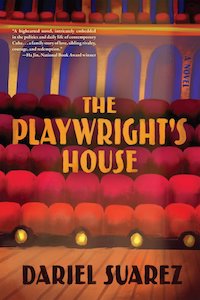

The Playwright’s House is available from Red Hen Press. Copyright © 2021 by Dariel Suarez.

Dariel Suarez

Dariel Suarez was born in Havana, Cuba and immigrated to the United States with his family in 1997. His debut story collection, A Kind of Solitude, received the 2017 Spokane Prize for Short Fiction and the 2019 International Latino Book Award for Best Collection of Short Stories. Dariel is an inaugural City of Boston Artist Fellow and Education Director at GrubStreet. His prose has appeared in numerous publications, including the Threepenny Review, Prairie Schooner, the Kenyon Review, and the Caribbean Writer, where he was awarded the First Lady Cecile de Jongh Literary Prize. Dariel earned his MFA in Fiction at Boston University and currently resides in the Boston area with his wife and daughter.