To love beyond boundaries is the most radical of acts. It also requires optimism. Richard Loving must have followed the light of his surname. In news clips he didn’t smile much, perhaps because his teeth were irregular. He didn’t look the part of an ardent integrator. His buzz cut, rugged face, and tobacco-scarred Southern accent marked him as a white, working rural man of simple means and tastes.

Like many Southerners, Loving knew people of color. But his relations with them were more intimate than most whites were willing to countenance. His father worked on a farm for a prosperous man of color, and his parents’ home was “down in the community where all the Indians lived,” according to a resident. Loving and friends would gather at a favorite bend in the road or at the back of a general store they had turned into a juke joint. Someone would bring a guitar or a fiddle, and this motley crew would play music and hang out together. They were black, white, racially ambiguous “high yellow,” or “Indian,” depending on the perspective of who was observing and who was claiming labels. Their crossing of color lines irritated the county sheriff, who literally was the race police and tried to break up their fun. Loving was perhaps the most culturally dexterous among this group. He could blend in with anybody, people said.1 He was playful and lived the life he wanted, loved the red-brown girl he wanted, drag-raced cars with his high-yellow friends. In the 1950s, in Central Point, Virginia—a hamlet with a penchant for race mixing—he and others willfully defied the old Jim Crow.

Mildred Jeter Loving accorded with central casting. In a documentary about the couple and the Supreme Court case that she and her husband brought fifty years ago, she played herself better than any actress could. She was dignified, slender, and pretty, with a quiet voice that made people lean in to hear her. Richard called her “Bean,” short for “String Bean.” She dressed like the housewife that she was; her short, bobbed hair was fuzzy at the roots but ended in shiny curls that betrayed either her complicated lineage or the pressing comb. She appeared to be a Negro or colored, words then used to describe African Americans, although as this book later describes, she identified herself as a descendant of an indigenous nation rather than slaves.

In 1958, Mildred and Richard were arrested and jailed for the felony crime of marrying. Virginia was among sixteen states in that era still sufficiently obsessed with the purity of its white citizens’ bloodlines to ban whites from marrying nonwhites, with varying definitions for who could claim whiteness. From 1661 until the Supreme Court ruled against such measures in the Loving case, forty-one states had enacted statutes that penalized interracial marriages. Every state with such laws discouraged or prohibited whites from marrying blacks, but many statutes also named other groups that could not intermarry with whites: Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, American Indians, native Hawaiians, and South Asians, among others.

There were legal bans, and there were social ones. Marrying, loving, and having sex across lines of phenotype were not considered normal or acceptable among most people in pre-civil-rights America. In 1958, only 4 percent of Americans approved of marriages between blacks and whites.

On June 12, 1967, the Supreme Court sided with the Lovings. The civil rights revolution had roiled from a Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, to a thousand similar nonviolent protests in over one hundred Southern cities, resulting in over twenty thousand arrests. When Police Commissioner Bull Connor turned water hoses and attack dogs on child protesters in Birmingham, Alabama, people of goodwill supported the protesters, as did moderate Republicans in Congress, who added their votes to overcome the staunch opposition of segregation-forever Southern Democrats. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred discrimination in education and employment and allowed people of color to dine, shop, and travel where they wanted. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 began to desegregate politics. In Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court added to the movement’s momentum.

“This infant step toward her personal liberation ultimately led to a transformation in national consciousness about the freedom to love.”Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for his unanimous brethren, plainly stated that Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage was “designed to maintain White Supremacy,” an objective no longer permitted by the Constitution. It was the first time the court used those potent words to name what the Civil War and the resulting Fourteenth Amendment should have defeated. Twice Warren mentioned “the doctrine of White Supremacy” animating these laws, implicitly acknowledging that the case was not only about intermarriage but also the ideology itself. This idea, created and propagated by patriarchs, had required separation in all forms of social relations. The ideology told whites in particular that they could not marry, sleep with, live near, play checkers with, much less ally politically with a black person. It built a wall that supremacists believed was necessary to elevate whiteness above all else. A dominant whiteness, constructed by law, was embedded in people’s habits. Perhaps Warren thought being transparent about this pervasive racial dogma would help cure the nation of its mental illness.

The onset of the long hot summer of 1967 may also have hastened the court’s desire to help dismantle the architecture of division. A race riot had erupted in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston on June 2 and raged for three days. The day before the court announced its Loving opinion, Tampa, Florida, had ignited. By the end of the year, 159 race riots had roiled the United States, most lethally in Detroit, where a police raid on an after-hours bar set off a revolt that ended five days later with forty-three deaths and two thousand injuries.

There was an “impasse in race relations,” as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delicately phrased it—a wide gap in perception between blacks and most whites about the aims of the civil rights movement and the riots. Black people were outraged by the inequality they suffered. They wanted opportunity and freedom from police harassment, squalor, and isolation. According to Dr. King, whites wanted improvement for the Negro, but not necessarily economic equality. When black folks moved beyond sitting down to order a hamburger to trying to integrate the neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools that whites dominated, a firm, even violent resistance ensued. Black people trapped in high-poverty ghettoes expressed rage at their limited possibilities, and white people considered riots evidence that blacks were unconstructive and undeserving. This was the impasse Dr. King described, alas, solely in terms of Negro and white. In 1967, the many-hued people of the United States were more focused on the Vietnam War and ameliorating or fleeing the aftermath of the riots than on the Lovings’ victory for quiet acts of interracial love. Mildred Loving was motivated more by her desperation to end her family’s years of exile from Virginia than by the civil rights movement. In lieu of prison, a Virginia judge had banished them from the state for twenty-five years. They had settled, unhappily, in Washington, DC, a world away from tight-knit Central Point. For Mildred, the last straw came when one of her children was hit by a car. At her cousin’s urging, she wrote a letter to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, asking for help. This infant step toward her personal liberation ultimately led to a transformation in national consciousness about the freedom to love.

Loving v. Virginia was one of a series of antiracist decisions by the Warren Court. Neither it, nor its famous predecessor, Brown v. Board of Education, would dismantle segregation, the enduring structures of white supremacy. While Loving removed legal barriers to interracial intimacy, the true import of the case is only beginning to emerge, as social barriers to interracial love have fallen and will continue to play out in coming decades.

In the long arc of history, the meaning of the case becomes clearer. It is impossible to understand America’s persistent race business without examining its origins, and antimiscegenation was an enduring protagonist. Enacting laws to ban or penalize interracial sex and marriage and stoking loathing about race mixing were key legal and rhetorical tools for constructing and propagating white supremacy. This ideology, in turn, was the organizing plank for regimes of oppression that were essential to American capitalism and expansion— from slavery, to indigenous and Mexican conquest, to exclusion of Asian and other immigrants, and, later, to Jim Crow.

For married couples, anniversaries mark time and the miracle that a marriage, whether rocky and redemptive, prosaic or blissful, has endured another year. The fiftieth anniversary of Loving v. Virginia is an apt time for reflection on the marriage of differences that is America and how we might improve, if not perfect, the Union.

Before Loving, lawgivers constructed whiteness as the preferred identity for citizen and country and then set about protecting this fictional white purity from mixture. Over three centuries, our nation was caught in a seemingly endless cycle of political and economic elites using law to separate light and dark people who might love one another or revolt together against supremacist regimes the economic elites created. After Loving, the game of divide and conquer continues, but rising interracial intimacy could alter tired scripts.

White people who have an intimate relationship with a person of color, particularly a black person, can lose the luxury of racial blindness if they really are in love with their paramour, their adopted child, their “ace” in that nonsexual way that one can adore a friend. They can lose their blindness and gain something tragic, yet real— the ability to see racism clearly and to weep for a loved one and a country that suffers because of it. For the culturally dexterous, race is more salient, not less, and difference is a source of wonder, not fear.

This transition from blindness to seeing, from anxiety to familiarity, that comes with intimate cross-racial contact is a process of acquiring dexterity. And if one chooses to undertake the effort, the process is never-ending. Some folks are more dexterous than others. Some, like Richard Loving, are more adventurous and get more practice than others at crossing boundaries or immersion in another culture. I do not make the simplistic and silly claim that interracial intimacy in and of itself will destroy white supremacy or eliminate race. Instead, I argue that a growing cohort is acquiring dexterity and race consciousness through intimate interracial contact, especially in dense metropolitan areas. Although I do not claim that every interracial relationship automatically confers such knowledge, many do, leading us on an arc toward less emotional segregation, of many but obviously not all whites choosing to work at adjusting to difference.

__________________________________

Adapted from the introduction to Loving: Interracial Intimacy in America and the Threat to White Supremacy by Sheryll Cashin (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

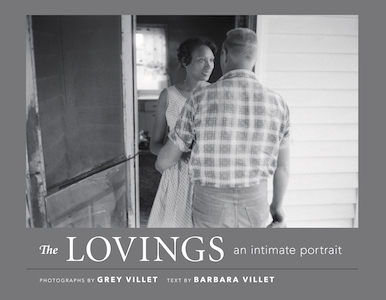

Photographs © Grey Villet, from The Lovings: An Intimate Portrait by Grey Villet and Barbara Villet, published by Princeton Architectural Press (2017)