Muslim America is Not a Monolith

Asma Uddin in the Complexities of the Liberal-Islam Coalition

“When I feel contempt, what should I do?” Arthur Brooks once asked a Buddhist leader.

“Show warmheartedness,” the Buddhist leader said. “What if I don’t feel warmhearted?” Brooks pressed. “Fake it,” the Buddhist replied.

In other words, attitude follows action. Choose the action and the feeling will follow. If you want to feel gratitude, act more grateful. And if you want to battle the culture of contempt, face contempt with warmheartedness.

We have to break our habit of contempt by reprogramming the parts of our brains that respond to that sort of stimulus. “Put something else in its place,” Brooks says. “Substitute a better behavior for a bad one. When you feel contempt rising up in front of you and you want to respond, increase the space between the stimulus and your response.”

This isn’t just a Buddhist teaching; it’s also what’s meant by the Christian injunction to “love your enemies” or the Qur’anic verse “Repel evil with good, and your enemy will become like an intimate friend” (41:34). In our polarized climate, though, the injunction can seem almost impossible to obey. I want to consider a few additional strategies attuned to our current predicament.

*

Unsorting is about complicating how we group ourselves and others into opposing camps. It creates a “partisan dealignment” and reveals “cross-cutting cleavages.” In the Christian-Muslim context, this process is aided when we begin to understand American Muslims for their fuller complexities.

We are beginning to see signs of that in the national discourse around gay marriage and homosexuality. In that conversation, Muslims and evangelicals are pitted against each other, with Muslims indisputably on the liberal or Democratic team. But as commentators are increasingly pointing out, the reality is far more complex.

“The way forward in the US political arena requires a synthesis of the best that both liberals and conservatives have to offer.”

It is true, according to the Pew Research Center, that Muslims’ support for same-sex marriage is growing, particularly among Muslim millennials (which includes those people who were born from 1981 to 1999 and came of age after 9/11). Only three in ten Muslim millennials believe that society should discourage homosexuality. Even among older American Muslims, almost half (44 percent) say that society should accept homosexuality. Overall, 52 percent of Muslims believe that society should accept homosexuality—compared to only 34 percent of white evangelicals who say the same thing. Religiosity is not the driving factor here; on coalition building with LGBTQ groups, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding’s (ISPU) 2020 American Muslim Poll found that political ideology and party affiliation are key drivers for Muslims, whereas religiosity has no predictive power.

That said, there’s work being done on the religion front, too. A number of Muslim scholars in America are reinterpreting Islamic sources on same-sex relations, and a few Muslim organizations, such as Muslims for Progressive Values and the Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity, are creating opportunities for gay Muslims to worship and engage meaningfully in the community. These initiatives, along with party affiliation and changing attitudes among Americans generally help explain the broad acceptance by American Muslims of homosexuality and same-sex marriage.

But it is also true that Muslims’ openness to homosexuality is in tension with traditional Islamic law, which doesn’t prescribe punishments for homosexual desire but does for homosexual behavior. According to Islamic law, sexual contact must be limited to married men and women, and marital intercourse is defined specifically as vaginal intercourse. The Qur’an tells the story of Sodom and condemns “its people’s overall immorality . . . specifically criticizing its men for ‘going to men out of desire instead of to women.’ Sodomy, understood as anal sex, was thus prohibited by the consensus of Muslim scholars . . .” Lesbian sex, while not sodomy, is also prohibited under the general rule against nonmarital sexual contact.

And despite growing acceptance, many American Muslims still hold conservative positions on homosexuality. A 2020 report by the ISPU found that while 48 percent of 18- to 29-year-old Muslims support coalition building with LGBTQ groups, only 38 percent of 30- to 49-year-olds and 26 percent of 50+-year-old Muslims support it. Overall, 55 percent of Muslims oppose forming political alliances with LGBTQ activists.

Religious scholars—including “rockstar imams” with massive followings—also encourage American Muslims to hew closer to traditional Muslim teachings. For example, in a widely circulated article targeting Muslim social justice activists, dozens of religious thinkers and community leaders urged the activists to “preserve all that is special about being Muslim” by prioritizing “the nonnegotiable teachings of Islam.” They also cautioned against forming alliances with “special interest groups” (either liberal or conservative) that would “unduly alienate large swaths of the demographic that activists and/or religious scholars themselves claim to represent.”

Instead, “the way forward in the US political arena requires a synthesis of the best that both liberals and conservatives have to offer,” and Islamic values should guide who we work with and on which issues: “Our main desire is that Islam and the preservation of its values be given priority and not sacrificed on the altar of political opportunism . . . Islamic mores [are] worth showcasing . . . even if they clash with those of our allies at times.” An influential Muslim leader, Dawud Walid, captured this approach in his book Towards Sacred Activism. Major conservative Muslim scholars negotiate traditional Islamic values and gay rights advocacy by both supporting the legal right to gay marriage and also taking a noncompromising position on the morality of homosexual relations. For example, a leading conservative Muslim scholar came out in full support of Obergefell when the case was decided, and says he would never turn away LGBTQ Muslims from the mosque or make them feel marginalized. But he also wrote a scathing critique of progressive Muslim activists who reinterpret Islamic law to support homosexual relations. In a Facebook post for his one million Facebook followers, the scholar, Yasir Qadhi, said “there is very little Islam” in what these activists advocate.

And in February 2020, Qadhi invited me to speak at an event at his mosque on religious liberty and gay marriage. There, he made clear that he sympathizes with the conservative Christian position in gay rights cases, and though he doesn’t think the Masterpiece scenario is likely to occur with Muslim business owners (he doesn’t think Islamic theology supports or requires a Muslim to refuse, for example, a custom wedding cake to a gay couple), he does worry about challenges to the rights of Muslim religious institutions to teach traditional Islamic doctrine and hire and fire employees on the basis of whether their sexual behavior conforms to traditional Islamic beliefs.

Though Qadhi has taken the lead here, he is by no means alone in his concern; many (if not all) conservative Muslims worry about preserving their way of life the way conservative Christians do. There is a growing gap between traditional Islam and the positions of Muslims’ political tribe (Democrats). When Beto O’Rourke declared during the 2019 CNN town hall that religious institutions should lose their tax-exempt status if they oppose same-sex marriage, John Inazu suggested in the Atlantic that

journalists should ask O’Rourke and every other Democratic candidate how this policy position would affect conservative black churches, mosques and other Islamic organizations, and orthodox Jewish communities, among others. It is difficult to understand how Democratic candidates can be “for” these communities—advocating tolerance along the way—if they are actively lobbying to put them out of business.

When I asked him to elaborate, Inazu said:

Many Muslim Americans hold social views similar to those held by Christian conservatives . . . non-religious Democrats pushing progressive policies they see aimed at Christian conservatives often fail to recognize—or at least acknowledge—how those policies will also harm Muslim Americans.

It remains to be seen how existing Muslim-liberal alliances will fare as these tensions continue to come to the fore. Conservatives generally agree that liberals will never target conservative Muslims the way they do conservative Christians. But others are less optimistic.

For example, Fuller Seminary professor Matthew Kaemingk tweeted in response to O’Rourke’s comment, “Muslims and the black church have historically enjoyed the warm embrace of the left,” but “Beto signals that, in the future, the left’s embrace could grow increasingly tight and even disciplinary.” Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times wrote in a confession of liberal intolerance, “We progressives believe in diversity, and we want women, blacks, Latinos, gays, and Muslims at the table—er, so long as they aren’t conservatives.”

The answer, as numerous Muslim scholars have noted, is not to switch tribes but to complicate our unassuming relationship with any tribe.

Meanwhile, Ben Sixsmith of the American Conservative warns of a liberal “subversion” of Islam, the manner in which the Left “pays cloying respect to the symbolism of Islam while undermining its significance.” This “subversion” happens most obviously with the Muslim headscarf, or hijab, and its modest dress codes generally. Sixsmith’s example is a Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue that featured a Muslim model wearing a clingy “burkini.” The burkini covered her body and hair, yet this “salute” to Islamic modesty “was superficial at best. While the model might have covered up, she was still lazing in the surf, her hands behind her head, as her swimsuit hugged her contours.” Sixmith argues:

The accidental subversive genius of American liberalism has been in presenting the hijab not as a symbol of faith but as a symbol of choice. . . . By encouraging Muslims to defend traditional dress on the grounds of choice, though, liberals and leftists have encouraged them to internalize individualistic standards. The hijab becomes less of a religious symbol, virtuously accepted according to God’s will, than an aspect of one’s personal identity, which one is free to shape and exhibit according to one’s wishes.

Such criticisms are common among Muslim commentators as well—me included. In 2016, I wrote in a similar vein when Noor Tagouri, a Muslim woman who wears a headscarf, was featured (fully clothed) in a Playboy interview on Muslim modesty. I doubted the magazine’s intentions. Playboy’s founder, Hugh Hefner, had a clear position on religiously mandated modesty and sexual ethics: he saw them, and most any other limit on public sexual expression, as fundamentally anti-freedom. What did it mean, then, when the magazine chose a woman in a headscarf to make, in its pages, a “forceful case for religious modesty”?

When the interview first came out, two other Muslim women who wear headscarves wrote publicly that they had also been approached by Playboy. The magazine appeared adamant about including the hijab in its pages, and I suspected it had something to do with redefining the nature of the hijab. I wrote, “Yes, Playboy has for a long time offered a range of hard-hitting political and social commentary unrelated to its pornography, but this topic in particular—religiously mandated modesty—does more than comment on a social phenomenon. Featured among overtly sexual content, a piece on Muslim modesty seems to mock and undermine those precise ideals. For many Muslim women, the hijab is about reclaiming ownership of their image—but the Playboy piece arguably takes away that agency and instead imposes its own frame, making the hijab sexy.”

I recognize, of course, that others might have more charitable interpretations of these Playboy and Sports Illustrated features. But it is indisputable that some tension exists between traditional Muslim values and practices and more liberal conceptions of sexuality. Increasingly, the popular discourse is becoming attuned to that tension.

The answer, as numerous Muslim scholars have noted, is not to switch tribes but to complicate our unassuming relationship with any tribe. They advise Muslims to strive toward a moral center; to place religious authenticity over and above any tribal loyalty.

There’s a role here for Christian conservatives, too. Princeton professor Robert George has long pleaded with his fellow Christian conservatives “not to push our Muslim fellow citizens away by fearing and despising them and causing them to fear and despise us.” But, he laments, “few conservatives have heeded me.” He continues to believe, though, that the same cross-cutting issues—fast-changing sexual norms, the corporatization of religion, and so on—that are triggering a gradual dealignment of American Muslims and the political Left can also serve as fruitful grounds for Muslim-Christian engagement.

__________________________________

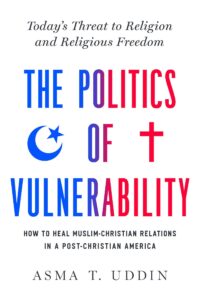

From The Politics of Vulnerability: How to Heal Muslim-Christian Relations in a Post-Christian America by Asma T. Uddin. Used with the permission of Pegasus Books.

Asma T. Uddin

Asma T. Uddin is a religious liberty lawyer who has worked on cases at the U.S. Supreme Court, federal appellate courts, and federal trial courts. She is the author of When Islam Is Not a Religion: Inside America's Fight for Religions Freedom, and the founding editor-in-chief of altmuslimah.com. Asma was an executive producer for the Emmy and Peabody-nominated docu-series, The Secret Life of Muslims. She has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Teen Vogue. Asma lives in Washington, DC.