Mario Vargas Llosa: How Global Entertainment Killed Culture

From Eliot to Steiner, Debord to Martel, Some Ideas on the Death of Meaning

It is very likely that never in human history have there been as many treatises, essays, theories and analyses focused on culture as there are today. This fact is even more surprising given that culture, in the meaning traditionally ascribed to the term, is now on the point of disappearing. And perhaps it has already disappeared, discreetly emptied of its content, and replaced by another content that distorts its earlier meaning.

This short essay does not intend to add to the large number of interpretations of contemporary culture but rather to explore the metamorphosis of what was still understood as culture when my generation was in school or at university, and the motley definitions that have replaced it, an adulteration that seems to have come about quite easily, without much resistance.

Before developing my own argument, I would like to explore, albeit in summary fashion, some of the essays that, in recent decades, have focused on this topic from different perspectives, and have at times stimulated important intellectual and political debates. Although they are very different from each other, and are only a small sample of the ideas and theses that the subject has inspired, they do share a common denominator in so far as they all agree that culture is in deep crisis and is in decline. The final analysis in this essay, by contrast, talks of a new culture built on the ruins of what it has come to replace.

I begin this review with the famous, and polemical, declaration by T. S. Eliot. Although it is only some 67 years since he published, in 1948, his essay Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, when we reread it today, it seems to refer to a very remote era, without any connection to the present.

T. S. Eliot assures us that his aim is merely to help define the concept of culture, but, in fact, his ambition is much greater, for, as well as specifying what the term means, he offers a penetrating criticism of the cultural system of his time, which, according to him, is becoming ever more distant from the ideal model that it represented in the past. In a sentence that might have appeared excessive at the time of writing, he argues, “I see no reason why the decay of culture should not proceed much further, and why we may not even anticipate a period, of some duration, of which it will be possible to say that it will have no culture.” (Anticipating my argument in Notes on the Death of Culture, I will say that the period Eliot is referring to is the one in which we are now living.)

That ideal older model, according to Eliot, is a culture made up of three “senses” of the term: the individual, the group or class, and the whole society. While there is some interaction between these three areas, each maintains a certain autonomy and develops in a state of constant tension with the others, within an order that allows the whole of society to prosper and maintain its cohesiveness.

T. S. Eliot states that what he calls “higher culture” is the domain of an elite, and he justifies this by asserting that “it is an essential condition of the preservation of the quality of the culture of a minority, that it should continue to be a minority culture.” Like the elite, social class is also a reality that must be maintained, because the caste or group that guarantees higher culture is drawn from these ranks, an elite that should not be completely identified with the privileged group or aristocracy from which most of its members are drawn. Each class has the culture that it produces and that is appropriate to it and although, naturally, these cultures coexist, there are also marked differences that have to do with the economic conditions of each. One cannot conceive of an identical aristocratic and rural culture, for example, even though both classes share many things, such as religion and language.

Eliot’s idea of class is not rigid or impermeable; rather it is open. A person from one class can move up or down a class, and it is good that this happens, even though it is an exception rather than the rule. This system both guarantees and expresses a social order, but today this order is fractured, which creates uncertainty about the future. The naive idea that, through education, one can transmit culture to all of society is destroying “higher culture,” because the only way of achieving this universal democratization of culture is by impoverishing culture, making it ever more superficial. Just as the elite is indispensable to Eliot’s conception of “higher culture,” so also it is fundamental that a society has regional cultures that both nurture national culture and also exist in their own right with a certain degree of independence. “It is important that a man should feel himself to be not merely a citizen of a particular nation, but a citizen of a particular part of his country, with local loyalties. These, like loyalty to class, arise out of loyalty to the family.”

Culture is transmitted through the family and when this institution ceases to function in an adequate way, the result is that “we must expect our culture to deteriorate.” Outside the family the main form of transmission of culture through the generations has been the Church, not the school. We should not confuse culture with knowledge. “Culture is not merely the sum of several activities, but a way of life,” a way of life where forms are as important as content. Knowledge is concerned with the evolution of technology and the sciences, and culture is something that predates knowledge, an attribute of the spirit, a sensibility and a cultivation of form that gives sense and direction to different spheres of knowledge.

Culture and religion are not the same thing, but they are not separable because culture was born within religion and even though, with the historical evolution of humanity, it has partially drawn away from religion, it will always be connected to its source of nourishment by a sort of umbilical cord. Religion, “while it lasts, and on its own level, gives an apparent meaning to life, provides the framework for a culture and protects the mass of humanity from boredom and despair.”

When he speaks of religion, T. S. Eliot is referring fundamentally to Christianity, which, he says, has made Europe what it is:

It is in Christianity that our arts have developed; it is in Christianity that the laws of Europe have—until recently—been rooted. It is against a background of Christianity that all our thought has significance. An individual European may not believe that the Christian Faith is true, and yet what he says, and makes, and does, will all spring out of his heritage of Christian culture and depend on that culture for its meaning. Only a Christian culture could have produced a Voltaire or a Nietzsche. I do not believe that the culture of Europe could survive the complete disappearance of the Christian Faith.

Eliot’s idea of society and culture brings to mind the structure of heaven, purgatory and hell in Dante’s Commedia with its superimposed circles and its rigid symmetries and hierarchies in which the divinity punishes evil and rewards good according to an intangible order.

Some 20 years after Eliot’s book was published, George Steiner replied to it, in 1971, in his In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Re-definition of Culture. In his concise and intense essay, Steiner is disturbed that the great poet of The Waste Land could have written a treatise on culture just three years after the end of the Second World War without linking his discussion in any way to the extraordinary carnage of the two world wars, and, above all, without mentioning the Holocaust, the extermination of six million Jews, the culmination of a long tradition of anti-Semitism within Western culture. Steiner proposes to remedy this defect with an analysis of culture that gives primacy to its association with political and social violence.

In Steiner’s account, after the French Revolution, Napoleon, the Napoleonic wars, the Bourbon Restoration and the triumph of the bourgeoisie in Europe, the Old Continent fell prey to “the great ennui,” a sense of frustration, tedium and melancholy, mixed in with a secret desire for explosive, cataclysmic violence, which can be found in the best European literature and in works such as Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. The Dada and surrealist movements were at the cutting edge and the most acute forms of this phenomenon. For Steiner, European culture did not simply anticipate but it also desired the prospect of a bloody and purging explosion that took shape in revolutions and in two world wars. Instead of stopping these bloodbaths, culture desired to provoke and celebrate them.

Steiner insinuates that perhaps the reason why Eliot had not encompassed “the phenomenology of mass murder as it took place in Europe, from the Spanish south to the frontiers of Russian Asia between 1936 and 1945,” was his anti-Semitism, private at first, but which the publication of some of his correspondence, after his death, would bring to public attention. His case is not exceptional because “there have been few attempts to relate the dominant phenomenon of 20th-century barbarism to a more general theory of culture.” And, Steiner adds,

Any theory of culture, any analysis of our present circumstance, which does not have at its pivot a consideration of the modes of terror that brought on the death, through war, starvation and deliberate massacre, of some seventy million human beings in Europe and Russia between the start of the First World War and the end of the Second, seems to me irresponsible.

Steiner’s explanation is closely associated with religion, which, in his opinion, is at the core of culture, as Eliot argued, but without Eliot’s narrow defence of “Christian discipline,” which is “now the most vulnerable aspect of his argument.” In Steiner’s argument, the “thrust of will” that gives rise to art and to disinterested thought, is “rooted in a gamble on transcendence.” This is the religious aspect of every culture. Western culture has been plagued by anti-Semitism from time immemorial, and the reason for this is religious. It is a vengeful response of the non-Jewish world to a people who invented monotheism, that is, the concept of a unique, invisible, inconceivable and all-powerful god who is beyond human comprehension and imagination. The Mosaic god came to replace the polytheism of gods and goddesses who were accessible to humanity in its different forms, and with whom diverse men and women could feel comfortable and get along. Christianity, for Steiner, with its saints, the mystery of the Trinity and the cult of the Virgin Mary, was always “a hybrid of monotheistic ideals and polytheistic practices,” which thus managed to revive some of the proliferation of divinities abolished by the monotheism of Moses. The unique, inconceivable god of the Jews is outside human reason—it is accessible only through faith—and it fell victim to the philosophes of the Enlightenment, who were convinced that a lay, secular culture would put an end to the violence and killings resulting from religious fanaticism, inquisitorial practices and wars of religion. But the death of God did not signify the advent of paradise on earth, but rather a hell, already prefigured in the Dantesque nightmare of the Commedia or in the pleasure palaces and torture chambers of the Marquis de Sade. The world, liberated from God, gradually became dominated by the devil, a spirit of evil, cruelty and destruction that would culminate in the world wars, the Nazi crematoriums and the Soviet Gulag. With this cataclysm culture came to an end and the era of post-culture began.

Steiner emphasizes that feelings of “self-indictment” or remorse are at the heart of the Western tradition: “What other races have turned in penitence to those whom they once enslaved, what other civilizations have morally indicted the brilliance of their own past? This reflex of self-scrutiny in the name of ethical absolutes is, once more, a characteristically Western, post-Voltairian act.”

One of the characteristics of post-culture is not to believe in progress, that history is on an ascendant curve. Instead we find a Kulturpessimismus or a new stoic realism. Curiously this attitude coexists with evidence that, in the fields of technology and scientific understanding, our era is producing miracles on a daily basis. But modern progress, we now know, often has a price to pay in terms of destruction, for example, with the irreparable damage done to nature and ecological systems, and it does not always serve to decrease poverty but rather to widen the chasm of inequality between countries, classes and peoples.

Post-culture has destroyed the myth that the humanities humanize. What so many optimistic educationalists and philosophers believed, that a liberal education accessible to all would guarantee a future of progress, peace, liberty and equality of opportunity in modern democracies, has not proved to be the case: “. . . the libraries, museums, theaters, universities, research centers, in and through which the transmission of the humanities and of the sciences mainly takes place, can prosper next to the concentration camps.” In individuals, as in society, high culture, sensibility and intelligence can, at times, coexist with the fanaticism of the torturer and the assassin. Heidegger was a Nazi, but he composed his great work on the philosophy of language within earshot of a death camp: “Heidegger’s pen did not stop, nor his mind go mute.”

In the stoic pessimism of post-culture, the security that certain differences and hierarchical value structures once offered have now disappeared: “The line of division separated the higher from the lower, the greater from the lesser; civilization from retarded primitivism, learning from ignorance, social privilege from subservience, seniority from immaturity, men from women. And each time ‘from’ stood also for ‘above.'” The collapse of these distinctions is now the most salient feature of contemporary culture.

Post-culture, which is sometimes also called, significantly, the “counter-culture,” can admonish culture for its elitism and for the traditional links that the arts, literature and science have had with political absolutism: “What good did high humanism do the oppressed mass of the community? What use was it when barbarism came?”

In his final chapters, Steiner sketches a rather gloomy picture of how culture might evolve, in which tradition, lacking any validity, would be confined to academia: “Already a dominant proportion of poetry, of religious thought, of art, has receded from personal immediacy into the keeping of the specialist.” What was previously active life will become the artificial life of the archive. And, worse still, culture will be the victim—it is already the victim—of what Steiner calls “the retreat from the word.” Traditionally, “spoken, remembered and written discourse was the backbone of consciousness.” Now the word is increasingly subordinated to the image. And to music, the “universal dialect” of the new generations, where rock and pop and folk music create an enveloping space, a world in which writing, studying and private communication “now take place in a field of strident vibrato.” What effect will this “musicalization” of our culture have on our brains, our mental faculties?

As well as stressing the progressive decline of the word, Steiner also points out as salient features of our time the preoccupation with nature and ecology and the prodigious development of the sciences—mathematics and natural sciences in the main—which has revealed unexpected aspects of human life, the natural world and atomic and interstellar space, and created techniques capable of altering and manipulating the brains and behavior of human beings. The “bookish” culture that Eliot referred to exclusively in his work is losing its vitality and it exists on the margins of contemporary culture, which has cut itself off almost exclusively from classical humanities—Hebrew, Greek and Latin—while the humanities themselves become the refuge of specialists who remain almost inaccessible due to their hermetic jargon, their asphyxiating erudition and their often delirious theories.

The most polemical part of Steiner’s essay is where he argues that postmodern society requires all cultured men and women to have a basic knowledge of mathematics and natural science so that they can understand the notable advances that the scientific world has made and continues to make in every area of chemistry, physics and astronomy, that are often as prodigious as the most audacious inventions of fantastic literature. This proposition is as utopian as those that Steiner decries in his essay, because if in the recent past it was unimaginable that a contemporary Pico della Mirandola would be capable of embracing all the knowledge of his time, in our age this would be out of reach even of those computers much admired by Steiner, with their infinite capacity for storing data. It is possible that culture is no longer possible in our age, but not for this reason given by Steiner, because the very idea of culture never implied any given quantity of knowledge, but rather a certain quality and sensitivity. As with Steiner’s other essays, this one begins with its feet on the ground and ends in an explosion of wild intellectual speculations.

A few years before Steiner’s essay, in November 1967, Guy Debord published in Paris La Société du spectacle, whose title is similar to the subtitle of my own collection of essays, although it approaches the theme of culture in different ways. Debord, an autodidact, a radical avant-garde thinker, a militant and a promoter of 1960s counter-cultural events, defines as “spectacle” what Marx called “alienation” in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, a condition caused by commodity fetishism, which, in advanced capitalist societies, has taken on such a central role in the life of consumers that it has displaced any other cultural, intellectual or political reality. The obsessive acquisition of manufactured products, which keeps commodity production actively increasing, brings about the “reification” of individuals, turns them into objects. Men and women become active consumers of objects—many of which are useless or superfluous—that fashion and advertising impose on them, emptying them of social, spiritual or even human concerns, isolating them and destroying their consciousness of others, of their class and of themselves to such an extent that, for example, the proletariat, “deproletarianized” by alienation, is no longer a danger, or even a form of opposition, to the dominant class.

These ideas of the young Marx, which he never managed to develop in his mature writings, are at the basis of Debord’s theory of our times. His central thesis is that in modern industrial society, where capitalism has triumphed and the working class has been (at least temporarily) defeated, alienation—the illusion of a lie that has become a truth—has taken over social existence, turning it into a representation in which everything that is spontaneous, authentic and genuine—the truth of humanity—has been replaced by artificiality and falsehood. In this world, things—commodities—have become the real controllers of life, the masters that men and women serve in order to guarantee the production that enriches the owners of the machines and industries that manufacture these commodities. “The spectacle,” Debord says, “is the effective dictatorship of illusion in modern society.”

Although in other areas Debord takes many liberties with Marxist theories, he accepts as canonical truth the theory of history as class struggle and the “reification” of men and women as a result of capitalism, which creates artificial needs, fashions and desires in order to maintain an ever-expanding market for manufactured goods. Written in an abstract and impersonal style, his book contains nine chapters and 221 propositions, some as short as aphorisms, and almost all lacking concrete examples. His arguments are at times difficult to follow given the intricate nature of his writing. Specifically cultural topics, relating to the arts and literature, are given only marginal coverage. His thesis is economic, philosophical and historical rather than cultural, an aspect of life that, faithful to classic Marxism, Debord reduces to a superstructure built on the relations of production that are the foundations of social existence.

This essay, by contrast, is anchored in the realm of culture, understood not as a mere epiphenomenon of social and economic life, but as an autonomous reality, made up of ideas, aesthetic and ethical values, and works of art and literature that interact with the rest of social existence, and that are often not mere reflections, but rather the wellsprings of social, economic, political and even religious phenomena.

Debord’s book has a number of insights and intuitions that coincide with certain topics that are explored in my essay, such as the idea that replacing life by representation, turning life into a spectator of itself, leads to an impoverishment of human existence (proposition 30). Likewise, his assertion that, in an environment in which life is no longer lived, but rather represented, one lives by proxy, like actors who portray their false lives on stage or screen: “The real consumer becomes a consumer of illusions” (proposition 47). This lucid observation has been amply confirmed in the years following the publication of Debord’s book.

This process, Debord states, leads to a sense of futility “which dominates modern society” due to the multiplication of commodities that the consumer can choose, and the disappearance of freedom because any social or political changes that occur are not due to the free choices of individuals, but rather to “the economic system, the dynamic of capitalism.”

Far removed from structuralism, which he calls a “cold dream,” Debord adds that any critique of the society of the spectacle will be possible only as part of a “practical” critique of the conditions that allow it to exist: practical in the sense of instigating revolutionary action that would bring an end to this society (proposition 203). In this respect, above all, his arguments are diametrically opposed to mine.

A large number of studies in recent years have looked to define the characteristics of contemporary culture within the context of the globalization of capitalism and of markets, and the extraordinary revolution in technology. One of the most incisive of these studies is Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy’s La cultura-mundo: Respuesta a una sociedad desorientada (Culture-World: Response to a Disoriented Society). It puts forward the idea that there is now an established global culture—a culture-world—that, as a result of the progressive erosion of borders due to market forces, and of scientific and technical revolutions (especially in the field of communications), is creating, for the first time in history, certain cultural values that are shared by societies and individuals across the five continents, values that can be shared equally despite different traditions, beliefs, and languages. This culture, unlike what had previously been defined as culture, is no longer elitist, erudite and exclusive, but rather a genuine “mass culture”:

Diametrically opposed to hermetic and elitist vanguard movements, this mass culture seeks to offer innovations that are accessible to the widest possible audience, which will entertain the greatest number of consumers. Its intention is to amuse and offer pleasure, to provide an easy and accessible escapism for everyone without the need for any specific educational background, without concrete and erudite references. What the culture industries invent is a culture transformed into articles of mass consumption.

This mass culture, according to the authors, is based on the predominance of image and sound over the word. The film industry, in particular Hollywood, “globalizes” movies, sending them to every country, and within each country, reaching every social group, because, like commercially available music and television, films are accessible to everyone and require no specialist background to be enjoyed. This process has been accelerated by the cybernetic revolution, the creation of social networks and the universal reach of the Internet. Not only has information broken through all barriers and become accessible to all, but almost every aspect of communication, art, politics, sport, religion, etc., has felt the reforming effects of the small screen: “The screen world has dislocated, desynchronized and deregulated the space—time of culture.”

All this is true, of course. What is not clear is whether what Lipovetsky and Serroy call the “culture-world” or mass culture (in which they include, for example, even the “culture of brands” of luxury objects), is, strictly speaking, culture, or if we are referring to essentially different things when we speak, on one hand, about an opera by Wagner or Nietzsche’s philosophy and, on the other hand, the films of Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford (two of my favorite directors), and an advertisement for Coca-Cola. They would say yes, that both categories are culture, while I think that there has been a change, or a Hegelian qualitative leap, that has turned this second category into something different from the first.

Furthermore, some assertions of La cultura-mundo seem questionable, such as the proposition that this new planetary culture has developed extreme individualism across the globe. Quite the reverse: the ways in which advertising and fashion shape and promote cultural products today are a major obstacle to the formation of independent individuals, capable of judging for themselves what they like, what they admire, or what they find disagreeable, deceitful or horrifying in these products. Rather than developing individuals, the culture-world stifles them, depriving them of lucidity and free will, causing them to react to the dominant “culture” with a conditioned, herd mentality, like Pavlov’s dogs reacting to the bell that rings for a meal.

Another of Lipovetsky’s and Serroy’s ideas that seems questionable is the assertion that because millions of tourists visit the Louvre, the Acropolis and the Greek amphitheaters in Sicily, then culture has lost none of its value, and still enjoys “a great legitimacy.” The authors seem not to notice that these mass visits to great museums and classic historical monuments do not illustrate a genuine interest in “high culture” (the term they use), but rather simple snobbery because the fact of having been in these places is part of the obligations of the perfect postmodern tourist. Instead of stimulating an interest in the classical past and its arts, these visits replace any form of serious study and investigation. A quick look is enough to satisfy people that their cultural conscience is clear. These tourist visits “on the lookout for distractions” undermine the real significance of these museums and monuments, putting them on the same level as other obligations of the perfect tourist: eating pasta and dancing a tarantella in Italy, applauding flamenco and cante jondo in Andalucía, and tasting escargots, visiting the Louvre and the Folies-Bergère in Paris.

In 2010, Flammarion in Paris published Mainstream by the sociologist Frédéric Martel. This book demonstrates that, to some extent, the “new culture” or the “culture-world” that Lipovetsky and Serroy speak of is already a thing of the past, out of kilter with the frantic maelstrom of our age. Martel’s book is fascinating and terrifying in its description of the “entertainment culture” that has replaced almost everywhere what scarcely half a century ago was understood as culture. Mainstream is, in effect, an ambitious study, drawing on hundreds of interviews from many parts of the world, of what, thanks to globalization and the audiovisual revolution, is now shared by people across five continents, despite differences in languages, religions and customs.

Martel’s study does not talk about books—the only one mentioned in its several hundred pages is Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, and the only woman writer mentioned is the film critic Pauline Kael—or about painting and sculpture, or about classical music and dance, or about philosophy or the humanities in general. Instead it talks exclusively about films, television programs, videogames, manga, rock, pop and rap concerts, videos and tablets and the “creative industries” that produce and promote them: that is, the entertainment enjoyed by the vast majority of people that has been replacing (and will end up finishing off) the culture of the past.

The author approves of this change, because, as a result, mainstream culture has swept away the cultural life of a small minority that had previously held a monopoly over culture; it has democratized it, putting it within everyone’s reach, and because the contents of this new culture seem to him to be perfectly attuned to modernity, to the great scientific and technological inventions of our era.

The accounts and the interviews collected by Martel, along with his own analysis, are instructive and quite representative of a reality that, until now, sociological and philosophical studies have not dared to address. The great majority of humanity does not engage with, produce or appreciate any form of culture other than what used to be considered by cultured people, disparagingly, as mere popular pastimes, with no links to the intellectual, artistic, and literary activities that were once at the heart of culture. This former culture is now dead, although it still survives in small social enclaves, without any influence on the mainstream.

The essential difference between the culture of the past and the entertainment of today is that the products of the former sought to transcend mere present time, to endure, to stay alive for future generations, while the products of the latter are made to be consumed instantly and disappear, like cake or popcorn. Tolstoy, Thomas Mann, still more Joyce and Faulkner, wrote books that looked to defeat death, outlive their authors and continue attracting and fascinating readers in the future. Brazilian soaps, Bollywood movies, and Shakira concerts do not look to exist any longer than the duration of their performance. They disappear and leave space for other equally successful and ephemeral products. Culture is entertainment and what is not entertaining is not culture.

Martel’s investigation shows that this is today a global phenomenon, something that is occurring for the first time in history, in which developed and underdeveloped countries participate, no matter how different their traditions, beliefs or systems of government although, of course, each country and society will display certain differences in terms of detail and nuance with regard to films, soap operas, songs, manga, animation, etc.

What this new culture needs is mass industrial production and commercial success. The difference between price and value has disappeared; they are now the same thing, where price has absorbed and cancelled out value. What is successful and sells is good, and what fails or does not reach the public is bad. The only value is commercial value. The disappearance of the old culture implied the disappearance of the old concept of value. The only existing value is now what the market dictates.

From T. S. Eliot to Frédéric Martel, the idea of culture has witnessed much more than a gradual evolution: instead it has seen a traumatic change, in which a new reality has appeared that contains only scant traces of what it has replaced.

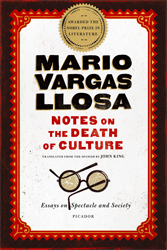

From NOTES ON THE DEATH OF CULTURE. Used with permission of Picador. Copyright © 2012 by Mario Vargas Llosa. Translation copyright © 2015 by John King.