Looking to the Past to Change the Future: On Japan's #MeToo Movement

Shiori Ito on Her Widely Publicized Assault Case, and Ensuing Activism

On May 29, 2017, I held a press conference at the Tokyo District Court. The purpose of the press conference was to publicize my appeal to the Committee for the Inquest of the Prosecution to reopen the investigation in the report I filed claiming to have been raped, which the Public Prosecutor’s Office had decided to drop.

The incident in question had in fact occurred more than two years earlier.

The press conference was likely the first time many of those present learned of the assault. Yet, over the course of those two years, how many times had I repeated the same story—to the police, to lawyers, and to various members of the press?

At the time, an amendment to the criminal law concerning rape crimes had been proposed in the National Diet, as the Japanese parliament is called. The criminal code regarding rape crimes dated back to 1907, without any major revisions having been made over the past 110 years. This old-fashioned and outdated legal system stipulated that a person cannot be charged with a crime unless the victim files a formal complaint to prosecute. Deliberations about the amendment had been postponed, and I found myself wondering whether the Diet would ever actually pass the amendment.

There were numerous other reforms that needed to be made—not only this amendment to criminal law, but also how investigations were conducted with victims of sex crimes, not to mention society’s general attitude toward them.

I needed to communicate all of this in my own words, with my own voice. If I waited for someone else to speak out, things would never change. I had finally begun to realize that myself.

This was the moment for me to come forward, with my own name and my own face on display, and for people at last to hear what I wanted to say.

*

On September 22, 2017, the Committee for the Inquest of the Prosecution announced its determination: “Nonprosecutable. Case dismissed.”

The Japanese criminal code regarding rape crimes dated back to 1907, without any major revisions having been made over the past 110 years.

Their conclusion sided with the prosecutor’s decision.

But what “facts” did the committee base their decision on?

I had been told by the prosecutor in charge of my case that, because the assault occurred behind closed doors, the incident was a “black box.”

In the days and months and years since then, as one of the parties involved and as a journalist, I have focused my efforts on how to shine light into this black box.

But each time I thought I’d pried open that box, I found yet another within the legal and investigative systems in Japan.

I hope by reading this you will learn what happened that day—the facts that became clear through my own experience; the account of the other party, Noriyuki Yamaguchi; the investigation; and further research. I have no way of knowing what you will think about it all.

Nevertheless, if there is no possibility for this incident to be tried within the current legal system, then I believe it is for the benefit of the world we live in to reveal the details and circumstances of the attack, in the hope of fostering a broader discussion within our society.

*

When people hear the word “rape,” many probably imagine a situation in which a woman is suddenly attacked by a stranger in a dark alley.

But in a survey conducted in 2014 by the Cabinet Office of the Japanese government, the percentage of cases in which a woman was forced to have sexual intercourse against her will with a total stranger was only 11.1 percent. The vast majority of cases involve victims who are acquainted with their assailant. Just 4.3 percent of all assault victims go to the police, and of that percentage, half were raped by a stranger, which makes it seem much more prevalent.

Why was I raped? There is no answer to this question. I have blamed myself, over and over. It’s simply something that happened to me.

In circumstances where the victim is acquainted with their assailant, it proves difficult to report the incident to the police. And under Japan’s current legislative system, if the victim was unconscious when the crime occurred, there are tremendous hurdles to prosecuting.

This was true in my case.

*

If you are taking the time to read this, I wonder what you may already know about me. Do you think of me as the woman who was raped, the woman who had the courage to hold a press conference, or the woman who appeared on TV with her shirt not buttoned all the way up when she was discussing rape?

After the press conference, whenever I saw the “Shiori Ito” portrayed in the media, it felt as though I was watching someone I didn’t know.

There were all kinds of things on the internet about this other, unfamiliar “Shiori” who looked just like me: she was a North Korean spy, a graduate of Osaka University, a dominatrix, politically motivated—these and all manner of unrelated and unheard-of details appeared alongside my picture. It was appalling the extent to which my family and friends—whom I had wanted to protect—were scrutinized. A month after the press conference, I heard from my friends that people were wondering where I was or saying that I had vanished.

But I was leading my life, the same way as before. I hadn’t gone anywhere, and I hadn’t disappeared.

*

Many things can happen in your lifetime: events you never imagined, stories like the ones you see on television, things you thought only happened to other people much different from yourself.

I aspired to become a journalist. I studied journalism and photography at an American university, and after returning to Japan in 2015, I began an internship at Reuters. And just then, something happened that changed my life forever. I had traveled to over sixty different countries; I had interviewed Colombian guerrillas and reported on stories from the cocaine jungles of Peru. When people heard this, they always said, “You must really have been putting yourself at risk!”

But while I was covering stories in such remote areas of these countries, I never felt at risk. The place where I encountered real danger was in Asia, in my own famously “safe” country—Japan. And the events that transpired afterward were even more devastating. The hospital, the hotlines, the police—none of these institutions were there to save me.

I was astounded to realize this about the society I had been living in so blissfully unaware.

*

Sexual violence causes unwanted fear and pain for all its victims. Our trauma continues for a long time afterward.

Why was I raped? There is no definitive answer to this question. I have blamed myself, over and over. It’s simply something that happened to me. And unfortunately, no one can change what happened.

I want to believe this experience isn’t in vain. When it happened to me, I had never been in so much pain. At first, I had absolutely no idea how to deal with such an unimaginable event.

Now I know what needs to be done. And in order to accomplish this, we must make changes—simultaneously—to the societal and legal systems that handle sexual violence. Above all, I hope to enable a society in which we can discuss trauma more openly. For the sake of myself, for my sister and the friends I love, for the children of the future, including my own, and for the many people whose names and faces I don’t know.

Keeping my shame and anger to myself wouldn’t have changed anything. That is why I decided to write this book—to speak my mind and to expose the problems that need to be addressed.

At the risk of repeating myself, I did not write this book because I wanted to tell the story about “what happened.”

I want to raise questions such as “How can we prevent assault from happening?” and “When assault does happen to someone, how can they get the help they need?” The only reason I even bother to bring up the past is so that we can strive to have these discussions in the future.

__________________________________

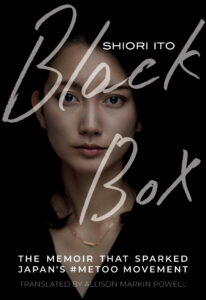

From Black Box by Shiori Ito. Published by the Feminist Press in July 2021. Reproduced with permission.

Shiori Ito, translated by Allison Markin Powell

Shiori Ito is a freelance journalist who contributes news footage and documentaries to the Economist, Al Jazeera, Reuters, and other primarily non-Japanese media outlets. She was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People of 2020.

Allison Markin Powell has been awarded grants from English PEN and the NEA, and the 2020 PEN Translation Prize for The Ten Loves of Nishino by Hiromi Kawakami. She is based in New York.