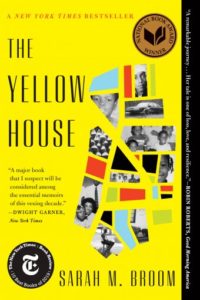

Looking Back to the Devastation of Katrina, 15 Years Later

Sarah Broom on a Disaster Almost 100 Years in the Making

Betsy

Nineteen sixty-five. Tail end of a notably mild hurricane season. It rained so hard the yards between the houses flooded—standing water for three days—but that was normal. This mid-September storm was erratic, busybodied; it seemed not to be able to make up its mind on where to go. “Wandering Hurricane Betsy, large and tempestuous,” the newspapers said.

The house was full of babies. Karen was not yet one; that birthday was two weeks away. Carl had just turned two. Michael was five. Darryl, four. Valeria, eight.

Simon had been called by NASA to join the emergency crew piling sandbags, but that was just in case. He expected to get right back. And anyway, Uncle Joe was staying at the house then. He was in between loves. No one knew the details, but some woman had put him out, or he had left some woman. Neither scenario was unusual for him.

“We all went to bed,” says Deborah.

Last she knew, the hurricane had turned, was headed to coastal Florida.

“All of a sudden I hear: ‘Get out the bed. Now, now, now.’”

It was midnight.

“We put our feet down on the floor.”

Water.

The house turned frantic.

Miss Ivory said, “Get the baby bag.” Karen was the baby.

*

Later, it was said that the water rose 20 feet in 15 minutes.

There was no attic to climb up into, no way to sit above it all to wait it out. When Uncle Joe opened the front door, water bum-rushed him. Deborah panicked: “We gon die, we gon die.”

“She started screaming at the top of her lungs like a person going crazy. So I slapped the piss out of her,” says Uncle Joe now. “Shut up,” he remembers saying. “This ain’t no damn movie.”

The water was waist-deep on the two adults. They waded through snakes and downed wires toward the high ground of Chef Menteur Highway, which was, for once, carless, to shelter in Mr. LaNasa’s high-sitting trailer park business at the corner.

Carl rode Uncle Joe’s back, Deborah his side, holding tight to the baby bag. Mom had Karen and Valeria, one on either hip.

Eddie, Michael, and Darryl swam like fish.

“I was a tiny boy,” says Michael. “Water was so high. I’m swimming, I’m swimming. The dogs, too. The water was moving through here like we was in a river.”

He’s right. The water was sweeping us down the street.

The water had in fact swept in like a river, its course and fury made possible by many things, most of them man-made. Poorly constructed levees, for one. And two: navigation canals touted as great economic engines that would raise the profile of a weakened Port of New Orleans by creating more efficient water routes that would, it was hoped, draw more commercial traffic.

The Industrial Canal, dredged in 1923, physically separating New Orleans East from the rest of the city in order to link the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain, was the first. Then in 1942, the Intracoastal Waterway was expanded through eastern New Orleans to connect with the Industrial Canal. But in 1958, construction began on one, more damaging than the rest: 70 federally funded miles of watery channel linking the Gulf of Mexico to the heart of New Orleans, shortening ocean vessels’ travel distance by 63 miles. It would officially be named the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, but everyone would call it MR-GO.

This is how water came to be rushing in at the front door when Uncle Joe opened it; and how water came to flood more than 160,000 homes.

As with much of New Orleans East’s development, in the early days of MR-GO only its positives were touted. In 1956, Louisiana governor Earl K. Long praised the “inestimable value to (1) the immediate area through which it passes, (2) the state of Louisiana and the city and port of New Orleans, (3) and the entire Mississippi Valley.” When construction began in 1958, the marshes lit up in a dynamite explosion that BOOM, BOOM, BOOMED, debris flying 300 feet in the air, raining fragments and mud on the heads of scurrying city officials, “many of whom looked for cover that was nowhere to be found,” the local paper reported.

Mayor Chep Morrison called it “one of the miracles of our time that will have the effect of bringing another Mississippi River to New Orleans.” He could not know just how true his prophecy would turn out to be.

Soon after it was built, the environmental catastrophe MR-GO wrought would become evident. Ghost cypress tree trunks stood up everywhere in the water like witnesses, evidence of vanquished cypress forests. The now unrestrained salt water that flowed in from the Gulf would damage surrounding wetlands and lagoons, and erode the natural storm surge barrier protecting low-lying places like New Orleans East.

This is what happened during Hurricane Betsy: 100-plus-mile-per-hour winds blew in from the east, pushing swollen Gulf waters across Lake Borgne, a vast lagoon surrounded by marshes and open to the Gulf. Water entered the funnel formed by the Intracoastal Waterway and MR-GO. Within this network of man-made canals, the storm surge reached ten feet and topped the levees surrounding it, breaching some.

This is how water came to be rushing in at the front door when Uncle Joe opened it; and how water came to flood more than 160,000 homes, rising to eaves height in some. At the same time, Lake Pontchartrain’s surge entered the Industrial Canal and ruptured adjacent levees, including those in the Lower Ninth Ward, topographically higher than the East, but equally vulnerable for how close it is to the canal.

It was a flood so devastating that our neighbor Walter Davis said, “I was thinking, ‘Man, I can tell my grandkids about this.’ That’s how awesome Betsy was.” So awesome was Betsy that her name was retired from the tropical cyclone naming list. Governor John McKeithen vowed on television and on the radio, in front of everybody, that “nothing like this will ever happen again.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson flew into the Lower Ninth Ward the next day—the area, even then, was a drowned and abandoned symbol of water’s destructive power when facilitated by human error—declaring the city and surrounding areas a disaster zone and eventually pledging an $85 million protection plan that would rebuild levees and shore up flood protection systems, which would, in August 2005, 40 years after Betsy, fail.

*

Even though expanses of New Orleans East Inc.’s property lay underwater, development surged on. Everyone vowed to rebuild higher, better. The levees would be shored up by the government just as Lyndon Johnson promised. New Orleans East Inc. and other eastern developers would use this fact in their advertisements to lure more and more people to the area. And in 1968, Congress would spur this repopulation along by creating the National Flood Insurance Program, which allowed people to buy flood insurance at low rates, even and especially in dangerous flood zones.

*

August 28th, 2005–September 4th, 2005

Carl

You gotta realize . . . the Yellow House was up and running.

A few years after the Water, Carl reconstructed for me what happened.

Carl and Michael sat outside the house, near to the curb. They were grilling, a half gallon of gin between them. The Mississippi River on one side, Lake Pontchartrain on the other. They were in between water. People who were evacuating drove past the intersection where Chef Menteur met Wilson, heading west toward the city; from Chef Menteur Highway they could see the smoke rising off Carl and Michael’s grill.

You gotta realize, Mo. It’s August. It’s beautiful. A Sunday. I then cut all the grass, weed-eated and everything. Had it looking pretty.

Mike, I don’t b’lee I’m going nowhere, Carl had said.

“I know I ain’t going,” Michael said back.

The city had imposed a 6 p.m. curfew.

It got dark, got to be 8, 8:30, still no rain or nothing. Shit, see bout 11, 11:30 at night that’s when it started to rain. When Carl tells a story he always gives two close options for the truth.

He packed his ice chest and told Michael good-bye, nothing memorable, and drove off in his pickup truck. Michael left to find his girlfriend, Angela, at their house on Charbonnet Street in the Lower Ninth Ward to see where they might head. It was already too late; he knew he was not going far.

The Yellow House, where Carl lived off and on when he had fallen out with Monica, stayed behind. Cords stayed plugged into the walls. His boil pots sat underneath the kitchen sink. That’s what “the Yellow House was up and running” was meant to say.

Carl took Chef Menteur to Paris Road to Press Drive to the brick house where Monica lived with their three girls. The street was empty and quiet, not unlike its normal self. Carl did not know if anyone else was around. Why should he have needed to know? He was feeling good.

Mindy and Tiger, his Pekingese dogs, did not appear at the door when he entered, but soon they were running by his slippered feet. The house phone was already ringing. Even though it was 2005, Carl still did not have a cell phone, having no desire whatsoever to be reached.

Mama and them kept calling, Boy, get your ass out the house.

He sat in the recliner and watched the television.

Well fuck, by my drinking I had then fell asleep, full of that gin.

He woke and moved from the chair to the bed, but before he slept again he made small preparations, just based on feeling.

Monica had a big ole deep attic, so I put the steps down. I had already mapped it out in case I had to get out of there. I had a hatchet up there already with the bottled water. Had my gun, the same gun right there, had my water and everything, the meat cleaver.

See bout three, four in the morning, the dogs in the bed scratching me, licking on me.

Damn, it’s dark.

You could hear it storming outside. I put my feet down.

Water.

*

Sound like a damn freight train derailing. Shit crashing. Shit flying, hitting shit.

I can’t see nothing, but I know the house. I throw Mindy and them up the attic steps.

I go in the icebox take the water out there. Shit, bout five minutes later the icebox come off the ground. The icebox floating. I got to go up now myself, the water . . . I got pajamas on.

On the way back, swimming, saltwater rushed into Carl’s mouth. Two, three more days passed in the same way with nothing changing.

I took a pair of jeans, I still got them jeans, my Katrina jeans. I go up there. Just waiting. Just riding it out.

Sitting there looking at the water coming. I got my gun, I got a light on my head, I say damn the hurricane rolling out there.

That water coming up higher and higher.

Ivory Mae

My mother calls Harlem from Hattiesburg, says, “Water is now coming into the house. We’re calling for help.” The phone line cuts out right as she is speaking so that is all I have to go on for three days.

Carl

It’s been bout four, five hours. All a sudden, the water don’t look like it’s coming no higher. It just stopped right there, bout six or seven feet. You could hear all kind of birds then came through all the windows.

See when daybreak come, that water it start coming again, it start coming all the way now.

I got to start cutting now.

The water coming.

It’s daytime now. I can cut now. The water steady rising.

I said, Shit I gotta get through this attic now.

*

Never panic, Mo. You can never panic.

*

I’m cutting through that sucker. I got an ax, I’m cutting through that son of a bitch.

I was gonna shoot my way through it if it wasn’t gone cut. I was gonna blow some holes through that son of a bitch. I’m getting out that roof.

Once I got my head out, I looked round.

*

“Hey man, I thought y’all was gone,” someone on a roof several houses down called.

*

Water edged the roof. Carl’s green boat was nowhere in sight.

It’s hot outside now, you gotta realize. They had a bucket floating. That’s how I kept the roof at the pitch cool.

It’s beaming on that roof. That attic don’t cool down until nine or ten o’clock at night. We’d stay up and talk all the way till about midnight. Survival shit. If them people don’t come, we have to swim out of here or this or that. I said whenever y’all ready but let’s give it a couple days.

Back then, the old folks across the way was telling stories bout they had a big alligator in the water. I mean if I had to swim I would have but you ain’t gone get in no water and people saying they got an alligator.

*

After three days, me and another dude got in the water.

*

There were still rules in the new Old World.

You swam up the middle of the street. You knew the neighborhood. We never dove because you never knew if they had a post or something down there. We swam to where them old people was. We made sure they were all right. We stood there a couple of hours, one dude had food and was grilling and smoking cigarettes.

*

“You must have been hungry,” I say.

But if you eat you got to use the bathroom.

*

On the way back, swimming, saltwater rushed into Carl’s mouth.

Two, three more days passed in the same way with nothing changing.

Harlem

Five days since the levees broke. I sit cross-legged before the television set in my swamp-green painted room, watching CNN on mute, searching only for Carl’s white cotton socks pulled up high, size 13 feet. In the day-to-day, I neglect serious consideration of any newspaper article except to scan for names and faces of my beloveds—Michael, Carl, Ivory, Karen, Melvin, Brittany.

Imagine this being all that you can do. It is as paltry as it sounds.

Carl

They finally come get us, some white guys from Texas. They pulled up in an airboat to the pitch of the roof.

*

Seven days had gone by.

*

Carl was deposited on the interstate right before the point where the bridge rose. This was not the quiet of the roof. Carl saw many people he knew, people from all over, out of the East, out of the Lower Ninth Ward, out of the Desire Projects.

Army trucks were taking people from the bridge to the Convention Center, which had become an impromptu shelter, but there were the old and infirm who needed to go first and Carl was in good health with legs he could use. Mindy and them wasn’t on no leash. I had some Adidas tennis on, but they was so tight. I took the shoestrings off and made leashes.

He took the dogs on a long walk to the Convention Center, joined by several men, bending his six-foot-three-inch frame down to better grasp the strings. From New Orleans East, they walked the five miles to Martin Luther King Boulevard, then back around to the Convention Center, a long route to avoid Orleans, St. Bernard, and Claiborne Avenues, all of which were underwater.

The walk took all day. But Carl never went inside the Convention Center itself. He stayed on the perimeter watching the clamor. For him, nighttime was not for sleep: a certain time of the night dogs would run loose from sleeping owners, sprinting through the dreaming masses.

Harry Connick Jr. appeared with TV cameras and buses showed up.

I wasn’t worried about getting on no bus, Carl said, opening another beer. Look like a movie, like the world coming to an end, people was just running. People just trying to get the fuck out of Dodge.

After days as part of a growing crowd that seemed to go nowhere, Carl set out from the Convention Center with two men he knew from the Grove. They headed toward the interstate where they found a boat with paddles sitting at the base of the ramp at Claiborne and Orleans Avenues, close to where Carl normally spends Mardi Gras day.

Whoever left it must have kicked ass. I said, Let’s take that mutherfucker and get the fuck.

Me and the two dudes pattlin.

The men paddled down Orleans away from the Convention Center, away from Canal to Broad Street.

The water was so high you couldn’t even much see Ruth Chris Steak House.

*

Carl and the two men moved through the watery city, one boat among many, down Broad Street sand back down Canal before night.

You thinking that’s mannequins floating by you, but when you get by it that body smell so bad, it then swoll up big. Man that ain’t no mannequin, that’s a dead body.

*

Now water leaking in the fucking boat. One dude got a bucket throwing it out, two of us pattlin.

Can the body feel the crossing of a state line, even if the mind does not grasp? Was Grandmother’s forgetfulness like drinking from the River Lethe?

They headed down Canal Street toward the Regional Transit Authority building where Monica worked, but by then it had already been evacuated. That night the men stayed in the boat, tethered to the massive metal rollup gates in front of the building’s parking lot, stranded cars and buses just inside.

Just like we were fishing somewhere. We just sit up in the boat all night smoking cigarettes and talking. Nodding off, fighting sleep.

That next morning they woke to the same watery city as the day before, but now there were boats with motors. That was the sound that woke them.

From the boat, Carl tried to see the next stage of things. The Dome—wasn’t nobody moving out. Convention Center, same. So now we all the way up Broad Street and Tulane. Now, what you think is there? What’s there, Mo?

I hesitate. It’s a geography test. I don’t know.

Orleans Parish Prison where inmates—some of whom were evacuated four days after the water rose to their chests—waited on top of the Broad Street Overpass in orange jumpsuits. Carl pulled his boat up to the bridge where other boats idled.

After the helicopter took all of the inmates, Carl headed to the top of the bridge instead of milling about at the foot with the others.

*

Helicopter was a big ole sucker, bigger than this damn house here. They always land at work, but I never rode on none of them hard-riding bastards. I say hey to the dude who was flying, Man where you taking us.

It was a rough ride. Mindy and Tiger bucked and pulled. Tiger was Mindy’s son and they acted it.

I’m home free now. I’m there now, said Carl, placing himself in the landscape. He knew exactly where he was: Int’national Airport.

Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport.

*

Grandmother

A yellow school bus full of ailing nursing home patients made its way down the highway, which highway? Van Gogh said yellow is the color of divine clarity. Was Grandmother sitting on a seat, was it plush, was it fake leather like on school buses where when you sit the air releases, or was she lying on pillows on the floor? What of her arthritic knees? Were they hurting at all, did she say a single word, did she sing like normal, did she look around, did she have a flash of clarity?

That is the thing I want to know: Did she have a moment of lucidity in her Alzheimer’s-ridden mind? Can the body feel the crossing of a state line, even if the mind does not grasp? Was Grandmother’s forgetfulness like drinking from the River Lethe? Did it cast her into oblivion, I wonder, erase the landscape of her former life, and is this the only condition, this unknowing, under which one should cross over state lines, leaving your familiarity behind? Is this the only way to properly leave home?

*

September 29th–October 2nd, 2005

St. Rose, Louisiana

Before the Water, I had six siblings outside of Louisiana and five in or near New Orleans. In the After, there were two siblings in Louisiana; neither resided in New Orleans. Now ten people had to fly back home instead of six. Most all of us came for Grandmother’s funeral, as if on pilgrimage. Grandmother’s burial would be the last time for a long time that this many of us—ten of twelve children—were gathered together in the same room.

Michael arrived from San Antonio where he had already found work as a life insurance salesman, his days spent driving up and down roads where “it would stop being pavement, start being dirt, and then turn into water,” for US Credit Union, which “wasn’t government, but sounded like it.”

Byron and Troy and Karen and Herman drove from Vacaville together, 36 hours straight. They retrieved Darryl from his home in Southern California along the way.

Grandmother’s funeral marked Darryl’s second time back in Louisiana after leaving New Orleans eight years before when I was a senior in high school. It was my second time seeing him and talking to him since, the first time that I could remember meeting and holding his eyes.

Our eldest brother, Simon Jr., drove the 13 hours from North Carolina.

Lynette and I flew in together from New York City.

All of us children, which is who we adults became in the presence of our mother, stayed together in Grandmother’s house. This was the house that used to receive us regularly on weekends, for holidays and birthdays, for celebrations of all kinds. It was not lost on us that Grandmother’s house, which she had bought and intended as a family home, was the very place that would keep us now.

Michael kept everyone fed. When visitors from the neighborhood stopped by to pay condolences he always asked, “How y’all flied through the storm?”

We wanted to memorialize Grandmother in the newspaper with an obituary, calling the Times-Picayune frantically, day after day, at every mundane moment, on our way to the grocery store or seconds after pulling into the driveway, just before getting out. But the line stayed busy; no one ever answered.

Far fewer people came to Grandmother’s funeral than would have if an obituary had run. My mother mentioned this over and over. It felt wrong to me, too, not to have Grandmother’s death in newsprint for someone other than those of us in the family to know or for someone to dig up years later, just as I have found evidence of my father’s having lived—and died.

The evening before Grandmother’s burial, I stood watching my brothers from the hallway of Grandmother’s house. They paid me no mind, or they did not know I was there. Byron pushed against Darryl, his arms making an X across his chest, the movements less brusque, more tender.

Michael was drunk and outside the house peering through the glass doors into the garage, my brothers pretending not to see. Carl, already a twig, was gaunt eyed, socks to his kneecaps, his face hiccupped in an ongoing laugh. I can still hear him laughing at everything, Simon Broom’s shadow.

Suddenly a sound—deep, guttural—rang out through the house.

UggggghhhhhAhhhhhh.

The noise seemed to come from someone who had not spoken for a long while. The whole house ran to the back bedroom. Mom was on her knees pulling the sheets down off the side of the bed. None of us children had ever heard her cry.

*

October 3rd, 2005

New Orleans East

Those of us who wanted to see the Yellow House crowded into Byron’s car for the drive to New Orleans East. It felt like an out-of-state trip; there were roadblocks everywhere. But because Carl had returned to work at NASA not long after the storm, his work ID procured us entry. When we arrived at the checkpoint on Chef Menteur, Carl pressed his work badge up against the window. “I got a Michoud badge,” he said to the officer through the closed window. “I’m legal.”

Even with windows rolled up, the post-Water smell (chitlins, piss, stale water, lemon juice) forced its way through the air-conditioning vents. We drove on, along Chef Menteur Highway, where instead of working traffic lights there were stop signs planted low to the ground. Like flowers. The actual flowers were now dead. We drove past Lafon nursing home where Mom used to work.

The lot was full of abandoned cars, the building empty inside. I don’t remember the rest of the sights on our way to getting there. Remembering is a chair that it is hard to sit still in.

We arrived at Wilson Avenue and made the right turn.

Mom wore a white surgical mask. I glimpsed her through Byron’s front windshield, her body parallel to the Yellow House, facing Old Gentilly Road, her shoulders slightly tilted, sunk in the buttery leather front seat, a hand cradling one side of her face. We, her children—Byron, Lynette, Carl, Troy, and me—jolted to the house.

Birds were now living in our childhood home. When we approached it with its broken-out windows, they flew away, en masse.

The house looked as though a force, furious and mighty, crouching underneath, had lifted it from its foundation and thrown it slightly left; as though once having done that it had gone inside, to Lynette’s and my lavender-walled bedroom and extended both arms to press outward until the walls expanded, buckled, and then folded back on themselves. The front door sat wide open; a skinny tree angled its way inside.

And the cedar trees: once majestic, at least 25 feet tall, and full of leaves that I hid in as a small girl. An impossibility now, for the sole surviving one was puny and on the way to dead.

We poked our heads through the house’s blown-out windows—peered into the living room through the wide-open frames. Walked along the side and stood in front of the new entrance, a fourth door designed by Water. The house had split in two, the original structure separated from the later addition that Simon Broom, my father, built.

On the original section of the house, the yellow siding hung off like icicles, revealing green wood underneath. That was the house of my siblings, a green wooden house, not the Yellow House that I knew.

We did not enter, even though the house we knew beckoned. We stayed outside, looking through the one big crack.

Somehow, standing as we were—spaced perfectly apart—made me think of the time, a few days before Grandmother’s burial, when I wandered through Providence Memorial Cemetery with Lynette and Michael. It was an impromptu trip. Michael said he knew where our fathers were. “I got two daddies in one cemetery,” he bragged as we turned into the graveyard on Airline Highway.

Michael gestured toward one of the only trees in sight. Webb, his birth father, was buried over there, he seemed to know. It was a month after the Water; everything was still ruined. There was no grave tender to ask.

We walked and walked. Over to the tree then past the tree to the rows of graves beyond it.

“My daddy not buried too far from your daddy,” Michael kept saying. It was strange, his separating us out as siblings. It felt unnatural.

When we did find the men, they were nowhere near where Michael thought, but they were close together in the ground. I had never seen the burial spot of my father, Simon Broom. I learned his birthday—February 22nd—for the first time on that day and saw that he had died on June 14th, 1980.

The three of us stood apart saying nothing whatsoever. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do.

At the cemetery that day, there was little to look at, unlike this moment outside the Yellow House where there was too much detail for the eyes to make sense of: The white plastic art deco chandelier dangled from a white cord in the girls’ room. A pair of Carl’s pants in a dry cleaner’s bag hung from the curtain rod. The white dresser that was painted over so many times that the drawers were permanently shut, the dresser Lynette and I used to pose in front of, where I would make rabbit ears behind her Jheri-curled head.

I felt that old, childish shame again. I did want the Yellow House gone, but mostly from mind, wanted to be free from its lock and chain of memory, but did not, could not, foresee water bumrushing it. I still imagined, standing there, that it would one day be rebuilt.

*

Carl needed to go back to Monica’s house, from where he escaped the flood, for his weed eater, he announced after we were settled back into the car. At Monica’s, Carl entered through a wooden fence, crumpled like an accordion. I photographed his every movement as if to save him from disappearance. Mom kept yelling from the car: Just leave the damn thing, Carl. I’ll get you another one. Come on now, boy.

Her voice was resigned, muffled by the mask.

But Carl always does what his mind wants. Next we saw, he was up on the roof walking with a loping stride.

Picture a man set against a wide blue sky, wearing a bright-red Detroit Pistons hat, blue jean shorts that fall far below the knee, and clean blue sneakers. In the first frame, he is bent down, holding himself up by his hands, entering the escape hole, a rugged map carved through the roof, feet first. By the second frame he is shrunken to half a man. In the last frame, we see only his head. Then he disappears inside.

*

Carl reappeared holding a weed eater in one hand, a chain saw in the other.

Now he was pointing at the hole in the roof. He was performing, his movements quick, wild but measured; he was earning his nickname. Rabbit. We formed a semicircle, looking up at him from the ground, as if poised to catch him.

Water will find a way into anything, even into a stone if you give it enough time. In our case, the water found a way out through the split in the girls’ room.

Come on, boy. Carl, come on now, get your ass down now. Leave that goddamn mess behind, my mother was still yelling. It was rare to hear her curse, but still we stayed watching Carl. None of us obeyed her command.

We were here, it was apparent, as witnesses to what Carl had come through. To retrieve, in some way, not the weed eater but the memory.

*

July 2006

Wilson Avenue

Water entered New Orleans East before anyplace else. On August 29th, 2005, around four in the morning, water rose in the Industrial Canal, seeped through structurally compromised gates, flowed into neighborhoods on both sides of the High Rise. But that was minor compared with what would come two hours later when a surge developed in the Intracoastal Waterway, creating a funnel, the pressure of which overtopped eastern levees, destroying them like molehills.

Water rushed in from in the direction of Almonaster Avenue, over the train tracks, over the Old Road where I learned to drive, through the junkyard that used to be Oak Haven trailer park, and into the alleyway behind the Yellow House, which may have served as a speed bump.

The water pushed out the walls that faced the yard between our house and Ms. Octavia’s. The standing water that remained inside caused the sheetrock to swell. Water will find a way into anything, even into a stone if you give it enough time. In our case, the water found a way out through the split in the girls’ room.

“Water has a perfect memory,” Toni Morrison has said, “and is forever trying to get back to where it was.”

*

The foundation of the Yellow House was sill on piers, beams supported by freestanding brick piles. Not an uncommon way of building in Louisiana, this foundation did not stand a chance against serious winds and serious flooding. The autopsy report testifies that our sill plate was severely damaged, that the connection was “pried or rotated.”

It could be said, too, an engineer friend told me, speaking more metaphorically than she was comfortable with, that the house was not tethered to its foundation, that what held the house to its foundation of sill on piers, wood on bricks, was the weight of us all in the house, the weight of the house itself, the weight of our things in the house. This is the only explanation I want to accept.

*

The house contained all of my frustrations and many of my aspirations, the hopes that it would one day shine again like it did in the world before me. The house’s disappearance from the landscape was not different from my father’s absence. His was a sudden erasure for my mother and siblings, a prolonged and present absence for me, an intriguing story with an ever-expanding middle that never drew to a close.

The house held my father inside of it, preserved; it bore his traces. As long as the house stood, containing these remnants, my father was not yet gone. And then suddenly, he was.

I had no home. Mine had fallen all the way down. I understood, then, that the place I never wanted to claim had, in fact, been containing me. We own what belongs to us whether we claim it or not. When the house fell down, it can be said, something in me opened up. Cracks help a house resolve internally its pressures and stresses, my engineer friend had said. Houses provide a frame that bears us up. Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up. I was now the house.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Yellow House. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press. Copyright © 2019 by Sarah M. Broom.

Sarah M. Broom

Sarah M. Broom's work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, Oxford American, and O, The Oprah Magazine among others. A native New Orleanian, she received her Masters in Journalism from the University of California, Berkeley in 2004. She was awarded a Whiting Foundation Creative Nonfiction Grant in 2016 and was a finalist for the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Creative Nonfiction in 2011. She has also been awarded fellowships at Djerassi Resident Artists Program and The MacDowell Colony. She lives between Harlem and New Orleans. The Yellow House is her first book.