AUGUST

Beverly Lowry, Deer Creek Drive: A Reckoning of Memory and Murder in the Mississippi Delta

Knopf, August 2

The true crime boom of the past few years (particularly in podcasts, and their resulting TV adaptations) has left me conflicted, because while I find much of its product to be salacious and fear-mongering, I find a well-constructed nonfiction crime narrative to be among the most compelling type of book. In Deer Creek Drive, Beverly Lowry tells the story of the murder of Idella Thompson, a society matron in the Mississippi Delta where Lowry grew up. After claiming that an unknown Black man had committed the murder, Thompson’s daughter was convicted, but was released from prison after six years, following a widespread community campaign. In the book, Lowry explores the crime and its wide-ranging ripple effects in the community and her own life. This promises to be a thoughtful and gripping addition to the true crime genre. –JG

T.J. English, Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld

William Morrow, August 2

As T. J. English proves in this fascinating new work of nonfiction, the history of jazz has always been inseparable from the history of vice and crime. That’s partly because of where jazz originated—New Orleans has always had plenty of bordellos, in the salons of which a new kind of music emerged in the 1880s. The gangsters liked the music, and they started patronizing clubs where “jass” music would play. The musicians liked the gangsters and the madams because both were far less racist and moralizing than the cops and cultural authorities of the time (and, well, today). And so, a truly American musical form was born and nurtured by those deemed as decadent as the music they enjoyed. –MO

Lynne Tillman, Mothercare: On Obligation, Love, Death, and Ambivalence

Soft Skull, August 2

When was the last time a subtitle alone sold me on a book? This might be the first. Cultural critic Lynne Tillman’s latest delves into the 11 years that she and her sisters spent caring for their mother at the end of her life, as she experienced an unusual medical condition that causes memory loss. Both a treatise on the “grueling obligation” of caregiving and an ineffectual American healthcare system, as well as the frank recounting of loving and living with a difficult parent, Mothercare feels particularly apt for an era in which caregivers are more burnt than out than ever (or, perhaps more accurately, an era in which we’re finally paying attention). –ES

Alec Nevala-Lee, Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller

Dey Street Books, August 2

This new biography of the multi-hyphenate American icon and futurist promises to dig deep into both his professional and personal life and frames him as the father of startup culture, showing how his ideas infected Silicon Valley and still hold sway today—whether you live in a geodesic dome or not. –ET

Emmanuel Carrère, tr. John Lambert, Yoga: A Novel

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, August 2

What will Emmanuel Carrère do next? This is the self-described story of a “breakdown,” beginning with a Buddhist meditation retreat that is cut short, followed by a series of events including breakdown of a marriage, depression, treatment in a psychiatric facility, and eventually a process of settling in Greece. This seems like a gripping story, and I can’t wait to read it. –CS

Mohsin Hamid, The Last White Man

Riverhead, August 2

Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West, published in 2017, was a gorgeously written story of two lovers struggling to maintain their lives across war and the brutality of contested borders. I couldn’t be more excited to read his upcoming book, which, like Exit West, shows two lovers grappling with the consequences of power and injustice: they face a world in which some people’s complexions have suddenly begun to darken and all the consequences that follow. –CS

Anthony Marra, Mercury Pictures Presents

Hogarth Press, August 2

Billed as “epic tale of a brilliant woman who must reinvent herself to survive, moving from Mussolini’s Italy to 1940s Los Angeles,” the second novel by Anthony Marra (A Constellation of Vital Phenomena) follows Maria Lagana, a Roman immigrant working for the troubled titular production company on the eve of America’s entry into WWII. Peopled by a cast of eccentric performers and European creatives-in-exile, Mercury Pictures Presents sounds like a thrilling and big-hearted love letter to mid-century Hollywood. –DS

Banana Yoshimoto, tr. Asa Yoneda, Dead-End Memories: Stories

Counterpoint, August 2

From the author of Lizard comes a new short story collection; originally published in Japan nearly a decade ago, these stories are evergreen. Dead-End Memories (a haunting title) follows several women, each one coming back to her life after a traumatic event. Although you will find heartbreak, ghosts, and betrayal humming in the background of these tales, you will also encounter a great deal of heart and optimism. Don’t we all need that right now? It’s the kind of collection that leaves you a little lighter. –KY

Kirk Wallace Johnson, The Fishermen and the Dragon: A Fight for Justice on the Texas Gulf Coast

Viking, August 2

Though The Fishermen and the Dragon is ostensibly an investigative accounting of past events (the Texas Gulf Coast in the late 1970s) it reveals much to us about our future. What happens when multinational corporations destroy traditional, local ways of life through greed, incompetence, and malfeasance? And then what happens when displaced communities, with no agenda other than to feed their families, are added to the mix? Kirk Wallace Johnson tries to answer these questions—and more—in this deeply reported story of struggling Texas Gulf Coast fishermen, Vietnamese refugees, rampant and widespread pollution, blatant xenophobia, and the deeply racist violence that inevitably ensues. There is a lesson here, and we’d better learn it fast. –JD

Robert Lowell; edited and with a preface by Steven Gould Axelrod and Grzegorz Kosc, Memoirs

FSG, August 2

The poet Robert Lowell (1917-1977) was a renowned writer and recipient of the National Book Award as well as the Pulitzer Prize for poetry twice over. But while he was a prolific and celebrated poet, Lowell dealt with his fair share of struggles. He suffered from severe bipolar disorder for most of his life, something that he discussed and alluded to in Life Studies, but his memoirs offer an open and honest account of what it was to grow up with his brain and his illness. Memoirs is predominantly made up of unpublished childhood memories that demonstrate who Robert Lowell will become, as well as who he was: a child in pain, trying to find a way forward, a way to heal. Writing may not have cured all, but it did allow us to experience the great work of someone who had been to the darkest places and back and lived to tell us of it. –JH

Sarah Thankam Mathews, All This Could Be Different

Viking, August 2

In Sarah Thankam Mathews’ debut novel, we are introduced to Sneha, a college graduate on the brink of a new life in Milwaukee. She’s got a corporate job that pays enough so she can send money home to India. She’s got a crew of new friends. She starts dating women and falls for one in particular, the ever-elusive Marina. But life has a way of unraveling just when things start to feel settled… All This Could Be Different promises to be a bildungsroman, an immigrant story, a hero’s journey not to be missed. –KY

Andrew Bacevich and Danny A. Sjursen (eds.), Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Long War

Metropolitan, August 2

We have not yet reached the one-year anniversary of American withdrawal from Afghanistan and already the disastrous fallout—at home and abroad—of this multigenerational forever war recedes from public consciousness. This cannot be allowed to happen. We *should* know by now that the half-life of a war and its effects goes on much longer than its official end date… and maybe we would if we spent more time listening to the soldiers themselves rather than the politicians who sent them away to die.

Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Long War, edited by Andrew Bacevich and retired army officer Danny A. Sjursen, shares the voices of post-9/11 veterans as they wrestle with the unimaginable moral and material debt accrued through over 20 years of largely misguided war. It takes courage in this country to speak out as a soldier, and if we are to avoid the kind of imperial folly that gave us the War on Terror, we will need to make more space for the voices of veterans who know of what they speak. This book does that. –JD

Amina Akhtar, Kismet

Thomas & Mercer, August 2

I’m a huge fan of Amina Akhtar’s cult classic debut, #FashionVictim, based on Akhtar’s experience working in the fashion magazine world. Her second novel skewers the wellness industry of Sedona (Amina Akhtar is now based in Arizona) and also includes a light supernatural touch that’s perfectly integrated into the thriller arc as a whole. In Kismet, a young desi woman follows her #livelaughlove mentor from New York to Sedona, befriends a bunch of ravens, and also solves some murders. Someone is killing extremely annoying people in this book, and readers may find themselves actively encouraging the killer. –MO

Emma Seckel, The Wild Hunt

Tin House, August 2

I never knew crows could be so creepy, but Emma Seckel schooled me in her richly imagined debut novel. Every year on the first of October, the crows arrive in threes—so many of them that the islanders off the coast of Scotland board up their homes for 30 days, instruct their children not to run under any circumstances (it attracts the birds), and celebrate the crows’ clockwork departure on the first of November.

But according to Celtic legend, these aren’t just any crows—they’re slaugh, ancient creatures known to ferry the souls of the dead. And in the solemn days after World War II, the slaugh are more numerous and aggressive than ever. When a young islander goes missing, Leigh Welles—harboring no small amount of guilt over feeling useless during the war, and no small amount of grief after her father’s recent death—teams up with the widowed RAF pilot Iain MacTavish—also guilt-ridden and reeling from the war—to investigate. A moving historical novel haunted by folklore and reality alike, best enjoyed during the slow slide from summer into fall. –ES

Alejandro Zambra, tr. Megan McDowell, Bonsai

Penguin Books, August 2

Bonsai has been praised the world over by now. The debut novel of the brilliant Alejandro Zambra, it was originally published in 2006 and drew well-deserved attention; now reissued by Penguin Books in a new translation by Megan McDowell, this is the perfect time to discover (or re-discover) it. Not a single word is wasted in this powerful, elegantly told story, which traces through a few episodes in the lives of Julio and Emilia, two young people who fall for one another at university—bonding over their love of literature and discussion—then retreat from one another’s lives.

This is the story of a love affair, but more to the point, it’s the story of all the moments that happen around, and after, an affair’s conclusion: the wondering, the distance, the passage of time that feels normal and not-normal all at once. A brief, striking story about all the imperceptible ways that lovers change one another (and the ways that they don’t), this book is unforgettable. –Corinne Segal, senior editor

Tess Gunty, The Rabbit Hutch

Knopf, August 2

In Vacca Vale, Indiana—a poisoned corner of the Midwest, where the chemical remnants of an abandoned auto industry have leached into the water of a town and the bodies of its residents—the inhabitants of an apartment complex nicknamed the Rabbit Hutch try to get by. At the story’s center is Blandine, an unusually intelligent young woman who’s fascinated by the writings of mystics, but who dropped out of high school; she lives with three boys who, along with Blandine, have aged out of the foster care system. (As you might expect, the boys are all obsessed with her.)

The four of them are surrounded by a varied cast of characters, from a new mother to a content moderator at a memorial website for the deceased and others; their private heartaches, longings, and fumblings toward connection drive the story forward. Gunty writes with such compassion for her characters as they build their lives and assert their agency in a country that utterly disregards them, and in particular Blandine’s bright, fierce curiosity for the world kept me moving through the story; she’s a warrior, an intellectual force, a young woman who refuses to be disempowered. This is a skillfully told, beautiful, human story. –CS

Megan Giddings, The Women Could Fly

Amistad, August 9

Lakewood author Megan Giddings offers a dystopian sophomore novel about 28-year-old Josephine Thomas, a Black woman who has never made sense of her mother’s disappearance. There’s the terrifying thought that Josephine doesn’t want to consider: was her mother a witch? Now, 14 years after her mother seemingly vanished into thin air, Josephine is fast approaching the state-mandated cut-off for marriage at age 30. Will Josephine learn the truth about her mother—and herself? I’m always down for stories about witches, especially if they’re about witches of color. In Giddings’s capable hands, I’m sure the narrative will be equal parts magic and revelatory. –Vanessa Willoughby, assistant editor

Emi Yagi, Diary of a Void

Viking, August 9

As Walker Caplan wrote in our Most Anticipated Books of 2022 roundup, Emi Yagi’s Diary of a Void has “one of the most fun premises I’ve heard of all year”—and fortunately, the premise pays off. Tired of making coffee and cleaning up after her male coworkers, single, 34-year-old Ms. Shibata makes a spontaneous announcement that she’s pregnant (whomst among us). Suddenly, her team stops expecting the most menial tasks to fall to her, she gets to leave work early (which is to say, at the decent hour of 5 pm), and she even makes a new circle of friends at a pregnancy aerobics class.

The latter is where this story really shone for me—Yagi captures Shibata’s loneliness and the community she’s granted upon “falling into step” with her married peers in such a keen way that, reading along, you’re on pins and needles to discover what will happen as this fake pregnancy runs its course. (You won’t get any spoilers out of me!) –ES

Jane Campbell, Cat Brushing

Grove, August 9

Eighty-year-old Jane Campbell’s elegant and necessary debut collection centers the experiences of older women who have long been deemed invisible in society. These 13 stories give us 13 different voices, the likes of which we’ve never heard: they are all women, past middle age, with a keen sense of their own mortality, but still with a hunger for experience and understanding. A dying woman experiences lust for the first time for the young nurse taking care of her in an elderly facility. A woman brushes her cat and remembers the pleasures of youth and sex, mourns what has past. Mysterious cuts and scratches found on a woman’s body foretell the end, though she doesn’t remember how she got them. A woman who believes her life is over meets a man on a train and finds love, but finds cruelty too. With serenity and the weight of years lived, Campbell sketches a quietly transgressive collection of characters both familiar and entirely new, sharp with grief and wit, and resolutely ready to tell their stories. –JH

Elliot Ackerman, The Fifth Act: America’s End in Afghanistan

Penguin Press, August 9

The history of the American invasion and occupation of Afghanistan is only beginning to be written, and it will likely be decades before a fuller picture emerges. But an early and important voice in that story will be that of writer and veteran Elliott Ackerman, who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. The history of any war will always be an ongoing collation of subjectivities—as such Ackerman brings his own deeply personal perspective as a marine (and later as a CIA paramilitary officer) who returns to Afghanistan on the eve of its return to the Taliban to help in impromptu, large-scale evacuations. Ackerman then works backward to look at 20 years of American misadventure in the Middle East, and the deep impact it has on two decades of his life. –JD

Jesse Ball, Autoportrait

Catapult, August 9

Jesse Ball’s memoir, inspired by the memoir Édouard Levé wrote shortly before his death, has been called “frank” and intimate” but I imagine its greatest strength is the clear and somewhat unsettling way in which Ball—as he does in his many novels—is able to pinpoint the best and worst of everyday life, of the basic situation of simply being alive, and make it strange and slightly absurd. “Autoportrait will leave you feeling utterly invigorated, inspired, and a little afraid.” Sounds about right! –EF

Italo Svevo, A Very Old Man: Stories

New York Review of Books, August 9

Italo Svevo achieved international acclaim as the author of Zeno’s Conscience, a modernist novel following the story of Zeno Cosini as he narrates his thoughts about family life, romantic misadventures, and the neuroses that make up his daily life. Now, NYRB Classics is issuing a set of five stories that Svevo wrote later in life; originally intended to be parts of a novel, they are available here to read in translation by Frederika Randall, with an introduction by Nathaniel Rich. It’s always fascinating to see a great writer’s work in progress; this is no exception, and is a great reason to revisit Svevo’s work in general. –CS

Michael W. Twitty, Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew

Amistad Press, August 9

Michael W. Twitty’s Koshersoul is an exploration of Black Jewish identity, lived and expressed through food. Twitty dives right into some of the more difficult conversations around Judaism and race, drawing on his own experience along with conversations with spiritual leaders and activists—always with a focus on the joy, ingenuity, and diversity of Black Jewish life.

In this interplay of history, Jewish teachings, and memoir, Twitty shows us the ways that he and others engage in a dialogue with their ancestors through food; a kitchen can be a sacred space, and nourishment in its many forms carries spiritual significance. There are recipes, too: “a koshersoul community cookbook of sorts,” filled with the knowledge of those whom Twitty interviewed. –CS

Kathleen Hale, Slenderman: Online Obsession, Mental Illness, and the Violent Crime of Two Midwestern Girls

Grove, August 16

Kathleen Hale’s Hazlitt piece on the Slenderman story still stands out from the general sensationalist coverage of the case for its level of empathy for all involved. When two middle schoolers stabbed another middle schooler in the woods in 2012, they claimed to do it on behalf of a mysterious figure known as Slenderman. Hysterical parenting sites spread a moral panic about CreepyPasta, the website where stories of Slenderman originated and then became memes. However, undiagnosed schizophrenia, midwestern stoicism, and intense friendship dynamics are much more to blame for the attack, as Kathleen Hale illustrates here. –MO

Gary Snyder, Uncollected Poems, Drafts, Fragments, and Translations

Counterpoint, August 16

Counterpoint Press continues to dole out the Gary Snyder goods: after such a long and storied career, with twenty-plus books under his belt, it’s impressive there is still new Snyder work to be read. Many of the works gathered here have been published in magazines or as singular broadsides, but just as many have been culled from Snyder’s letters and journals, and have never been published nor read by the public. –JH

Daisy Lafarge, Paul

Riverhead, August 16

In Lafarge’s debut, inspired by the exploits of artist Paul Gaugin, a young British graduate student goes to the south of France to work on a farm, and finds herself captivated by an older man, the eponymous Paul. Aja Gabel calls it an “essential portrait of the toxic power dynamics in romantic relationships, and a beautiful, immersive story about a young woman finding her voice,” which sounds like pretty decent summer reading to me. –ET

Anna Deforest, A History of Present Illness

Little, Brown, August 16

Anna Deforest’s brisk and brilliant debut follows a young woman beginning on her first day as a student doctor. Deforest (a physician herself) brings wit and beauty to scenes of cadaver dissection, brain death, abortion, and other matters routine to doctors and often shrouded in mystery to civilians. While comparisons to other beloved fragmentary writers will be inevitable, this book is unique, and spectacular. –JG

Édouard Louis, tr. Tash Aw, A Woman’s Battles and Transformations: A Novel

FSG, August 16

Edouard Louis’ latest book is an autobiographical novel, much in the vein of his earlier novels (his debut The End of Eddy chronicled growing up gay in working-class northern France and the more recent Who Killed My Father?, detailed his father’s accident and the ensuing emotional and physical violence he endured growing up). Now Louis turns the lens on his mother, Monique Bellegueule. Although he uses her real name, the narrative is non-linear, interjected with philosophy and family history, and maintains some of the mystery that keeps French journalists busy trying to fact check Louis’ art. While the narrative is pulled from his life, the personal is always political—and Louis tracks his mother’s violence and pain as intertwined with capitalism, patriarchy, and systems beyond our control. Translated by his friend and novelist Tash Aw, this is not to be missed. –EF

Brenda Lozano, Witches

Catapult, August 16

Two narratives come together in Brenda Lozano’s newly translated Witches: that of Feliciana, and Zoe, a journalist, who meet when Feliciana’s cousin, Paloma, is murdered. Feliciana tells the story of her experience as an Indigenous healer in Mexico, and her life with her trans cousin Paloma before her death. Eventually, these stories change the way Zoe sees not only the world but herself, and allow her to find her own path and voice. –JH

Beth Macy, Raising Lazarus: Hope, Justice, and the Future of America’s Overdose Crisis

Little, Brown, August 16

Macy’s follow-up to her bestselling Dopesick brings her essential reporting on the American opioid epidemic up to the present day, examining not only the political, financial, racial, and social elements at play, but also what happens when you throw a pandemic into the mix. –ET

Julian Barnes, Elizabeth Finch

Knopf, August 16

Barnes’ reputation precedes him as an immersive and gentle storyteller, someone transfixed with humanness, the mystery at the center of personhood, and most importantly, the fallibility of memory and story. In typical Barnesian fashion, Elizabeth Finch’s narrator, Neil, can trace the origin of his person, the turning point of his life, back to one season of his young adulthood. In this case, it is a class he took with the larger-than-life Elizabeth Finch, or EF, as we come to know her. She is a stoic, awe-inspiring professor who leaves her imprint on the minds of all those that come into her sphere—with nods to The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Barnes new novel revolves around this woman, what we know of her, what we will never know.

Perhaps one of Barnes’ most personal novels, he pulls almost direct quotes from his 2016 obituary of his real-life friend and novelist, Anita Brookner as he describes EF, a stand-in for Brookner, whom Barnes admired, respected, and never really understood. Elizabeth Finch is an interrogation of what it means to make a study of someone else, love someone, to be changed by someone, and to realize we maybe never have known them at all. –JH

Nina Mingya Powles, Magnolia

Tin House, August 16

At the risk of being reductive, I love a collection that combines poetry and pop culture, which Nina Mingya Powles’s Magnolia does to excellent effect. We begin with “Girl Warrior, or: Watching Mulan (1998) in Chinese with English Subtitles”; several stanzas in, Powles reveals to us where she’s coming from: “once a guy told me mixed girls are the most beautiful / because they aren’t really white / but they aren’t really Asian either.” The collection goes on to explore mixed-race girlhood and the confines of language and translation, as well as longing—for others, for a sense of home—in poems that play with both form and subject. I read it in my backyard on a warm spring day, just as everything was beginning to bud, which felt like the just right setting. –ES

Lauren Acampora, The Hundred Waters

Grove, August 23

Lauren Acampora’s The Paper Wasp, was one of my favorites of 2019. It was one of the most surprising and suspenseful novels I can remember reading. It’s strange in a way that feels elemental and necessary, as well as sad and scary and thrilling. I’m delighted to report that her latest novel, The Hundred Waters, manages to be both wholly different from The Paper Wasp, and every bit as exciting.

The Hundred Waters follows Louisa, a former model and artist, now living in a wealthy, staid Connecticut town while raising her 12-year-old daughter Sylvie and running the town’s sleepy art center. She and her daughter both become enchanted by the teenage son of a new couple in town, an artist and climate activist who seems both alluring and sinister. Questions of the pursuit of art, stagnation, youth and aging, and how to exist on a planet that is, increasingly, made up solely of emergencies, are grounded in the richness (no pun intended) of Sylvie and Louisa’s characters. And, as in The Paper Wasp, Acampora’s descriptions of the strangeness of artworks are not to be missed. –JG

Gaia Vince, Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape Our World

Flatiron, August 23

“We are facing a species emergency,” writes Vince, whose new book draws on two years of frontline research and a career in environmental journalism. “We can survive, but to do so will require a planned and deliberate migration of a kind humanity has never before undertaken. This is the biggest human crisis you’ve never heard of.” More good news, then. But better to be prepared, especially considering it’s already happening. –ET

Casey Parks, Diary of a Misfit

Casey Parks, Diary of a Misfit

Knopf, August 23

Casey Parks knew it would be a cataclysmic event when she told her Southern family about her queerness, but she didn’t know it jumpstart her own quest for answers. After telling her family she was a lesbian, her grandmother told her about “a woman who lived as a man,” Roy Hudgins, who used to live across from her many years ago. Her grandmother instructed Parks to track him down and find out what she could—and this she did, spending years looking for Roy, finding out how he lived, what he thought, how he managed his otherness in a place that did not celebrate it. Parks ends up finding a lot more than she bargained for, more about Roy, queer lineage, and her own relationship to her identity, faith, and family. This one’s not to be missed. –JH

Anya Kamenetz, The Stolen Year

Basic Books, August 23

You might know Anya Kamenetz as a voice on your radio reporting on the many ways in which American social policy—at the local, state, and federal levels—is letting down the nation’s children. As NPR’s education correspondent, Kamenetz has had a first-hand look at the impact of this country’s systematically dismantled social safety nets, the result of a multi-generational campaign that has left those most vulnerable with nowhere to go. And those most vulnerable are children.

If there was any doubt about the inability of American government to take care of its own, it was put to rest by our disastrous response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As Kamenetz documents in The Stolen Year—in which she interviews families across America, from all walks of life—children are always the first to suffer when there isn’t enough of anything, be it food, money, time, care, or shelter. We still cannot know the cost of these terrible years on the younger generation, but with The Stolen Year, we can at least begin the reckoning. –JD

Robert Crawford, Eliot After the Waste Land

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, August 23

The much anticipated follow up to Crawford’s Young Eliot, Eliot after ‘The Waste Land’ does what it says on the tin: tells the story of the poet’s life after the release of his grand opus. Eliot’s letters with long-time love, Emily Hale, were unlocked in the year 2020, and Crawford draws upon this unearthed trove of documents among others in his final biography. What emerges is the completed portrait of a man who has been in the public eye for over a hundred years, but has never before been seen in quite this way: the reader is treated to the intimate and tender correspondence between him and his great love, as well as a more comprehensive understanding of his work and career. –JH

Rasheed Newson, My Government Means to Kill Me

Flatiron, August 23

You don’t want to miss My Government Means to Kill Me, the debut novel from Rasheed Newson, producer and writer of such acclaimed series as Bel-Air, The Chi, and Narcos. His novel is a powerful story about Trey, a young, gay, Black man in 1980s New York City as he comes of age personally and politically. Newson’s writing is crisp and clear, witty and engrossing—the kind of prose that pulls you in so quickly you’ll miss your subway stop (and I did). Do you like footnotes? If so, then this is the book for you: extremely thoughtful and clever on narrative, thematic, and formal levels, unfolding meaning in every possible place, My Government Means to Kill Me is a tour-de-force. –OR

Ella King, Bad Fruit

Astra House, August 23

Bad Fruit occupies that liminal space between psychological thriller and horror, beautifully written and incredibly disturbing. In this lushly poisonous tale, we follow a teenage girl on the cusp of freedom from her tyrannical mother. Things take a turn towards the supernatural when she gains access to intergenerational memories and begins to finally understand her family’s strange behavior. Perfect for those who enjoyed Natsuo Kirino’s underrated mishmash of thriller and body horror, Grotesque. –MO

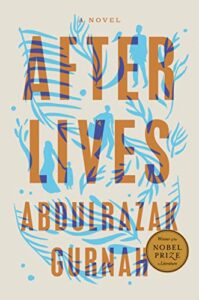

Abdulrazak Gurnah, Afterlives

Riverhead Books, August 23

When Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Nobel Prize in 2021 for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fates of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents,” American readers rushed to purchase his books; they found very little to buy, as many were out of print, and publishers soon began racing to correct the problem. Now, Afterlives—which was published by Bloomsbury in the UK in 2020—is coming to the US via Riverhead.

Afterlives is a sweeping look at multiple generations of a family as they navigate the shifting political climate in east Africa (present-day Tanzania), beginning with the era of German colonization through World War II. We’re introduced to Ilyas, who was kidnapped as a young boy and forced to serve with German forces, and his sister, Afiya, who, after Ilyas was taken and their parents died, lived with another family who abused her and forced her to work. When Ilyas comes back, he takes his sister to live in a nearby town, where she settles with friends as he voluntarily returns to the German army. It is in that town that Afiya encounters Hamza, reeling from his time serving with the same forces—the two of them fall in love and build a life together.

This is a look at the impossible decisions and violences that a community faces as the savage force of colonization rips through its social fabric; Gurnah’s deep insight into history, and his attentive narrative eye, make this an engrossing, moving read. –CS

Emma Donoghue, Haven

Little Brown, August 23

Twenty-first century living got you down? Wish you could disappear, even for a few hours, into an older, simpler, purer way of life? Well, it doesn’t get much purer than an extraordinarily inhospitable island off the west coast of Ireland, inhabited only by a massive colony of puffins and three severely under-resourced seventh century monks. In this brilliantly realized, utterly transporting new novel by Irish-Canadian author Emma Donoghue (Room, The Wonder), a pious traveling scholar-priest called Artt has a dream telling him to seek out a far-flung island, cut off from the sin and sloth of the modern world, on which to build a monastery. Taking with them minimal supplies (“God will provide”) Artt and a pair of bewildered but loyal new disciples—the awkward-but-seaworthy teenager Trian and the battered, late-in-life convert Cormac—set out in a currach, with nothing but faith as their compass, to discover what we now know as Skellig Michael (where, if you recall, old, bearded Luke Skywalker lives in one of those interminable new Star Wars movies).

Donoghue’s detailing of the island’s rugged geography and the methodical subsistence work of its dogged new stewards is masterful, almost hypnotic, but it’s the author’s quietly devastating depiction of the conflict between faith and survival, obedience and self-preservation, that powers this extraordinary novel. –DS

Joyce Carol Oates, Babysitter

Knopf, August 23

The latest novel to spring from the macabre imagination of octogenarian Twitter dynamo Joyce Carol Oates (the iconic, multi award-winning author of them, Blonde, Blackwater, and The Wheel of Love, to name but a few) is set the dying days of the 1970s as a series of unsolved child murders—committed by a serial killer known as Babysitter, who stalks the wealthy Detroit suburbs—upends the lives of a disparate group of residents. A slow-burning, 70s-set, serial-killer-in-suburbia yarn by one of the masters of American horror sounds to me like the perfect book for the waning days of summer. –DS

Alissa Quart, Bootstrapped: Liberating Ourselves from the American Dream

Ecco, August 30

Alissa Quart has long been an outspoken advocate for those millions (upon millions) of people left out of late capitalism’s endless get-rich-quick pyramid scheme, as a writer, journalist, and even a poet. In her latest work of longform journalism, Quart interrogates the pervasive—and pernicious—American myth of “bootstrapping,” that magical idea that if you only work hard enough, if you just dig a bit deeper, you too can have it all (regardless of the material circumstances of your birth). As income inequality grows ever wider in a country that seems to survive solely through a ragged network of GoFundMes and pay-day loans, Bootstrapped is an important reminder that sometimes asking for help is the real act of heroism. –JD