Lit Hub's Most Anticipated Books

of 2020, Part 2

A Reading List for Our Cursed Timeline

SEPTEMBER

Kerri Arsenault, Mill Town

St. Martin’s, September 1

What happens to a town created by an industry that then poisons it? Can people leave—why wouldn’t they? How many cities across America, let alone the world, would fit this category? Kerri Arsenault’s devastating debut book Mill Town is very much about a Maine village and its paper mill. She vividly brings to life the pride and lack of opportunities that keep people trapped there when the mills shut down, and cancer rates explode. But it’s also a story for our time, in which corporations decreate the environment with acts of slow violence. Drawing on deep and compassionate reporting, talking to her classmates from high school, neighbors, her own mother—Arsenault’s father died of cancer he probably contracted at the mill—this book makes visible the people whose lives have been treated as expendable, rendering them with humor and complexity. There are no answers here, just mourning. This book will be a classic of American nonfiction reporting for years to come, right up there with Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family, Matthew Desmond’s Evicted, and Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Emma Cline, Daddy

Penguin, September 1

As previously described: I must confess that I never got around to reading The Girls—Emma Cline’s blockbuster 2016 novel about a listless California teenager who gets sucked into the orbit of a Manson-like cult—but after reading Daddy, the author’s dark and brilliantly disquieting debut story collection, I fully intend on adding its predecessor to my TBR pile. Cline’s sharply-drawn characters are the cowed, contemplative survivors of self-inflicted trauma, both seismic and quotidian—from the father whose past anger issues have irreparably damaged his relationship with his daughter, to the nanny hiding from the paparazzi after the affair with her movie star boss is discovered, to the radioactive editor fleeing a workplace sexual misconduct scandal. We join them in the paralyzed aftermath—elegantly conjured limbos where regret is a constant companion. This all sounds dour, and I suppose it is, but Cline writes with such grace and precision that every sentence is a joy to absorb. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Etel Adnan, Shifting the Silence

Nightboat, September 1

Like the sea at night, this stark, but warm book moves in waves, the 93-year-old Lebanese poet and painter casting her mind back and forth in the room of its container. She contemplates the Greeks, the endless battle in Picasso between the sexes, coming tides which remain obscure. Hers is a restless moonlit searching, unassuaged before the big questions. Who is she speaking to, she wonders, and why? “There is a loneliness to any ending,” she ponders, then adds, mysteriously, “but we have felt even lonelier.” As if to prove it, “Shifting the Silence” evolves into a kind of diary, friends emerge and even call, come to visit her in Paris, which she describes with the brisk movements of a master painter. “It’s Paris now, under fog. The Eiffel tower is turned into a smudge, a faint mark on pure space. People’s hands are in their pockets, the river Seine feels icy. You have to walk fast to keep some warmth in you. All the international negotiations sound ridiculous compared to the simple, basic questions that we ask: do angels still care? Is the human species going to survive, and by the way, is this question really important?” –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Ricky Riccardi, Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong

Oxford University Press, September 1

Ricky Riccardi has devoted much of his professional life to the preservation of Louis Armstrong’s legacy. His next book looks at the under-recognized middle period of the musician’s life, when Armstrong laid the foundations for swing music and bebop. We remember Armstrong as that smiling man with the unforgettable voice, but Riccardi restores the great complexity of his life, highlighting a formative phase in which the musician experienced some of the lowest points of his career. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Arundhati Roy, Azadi: Freedom, Fascism, Fiction

Haymarket, September 1

Azadi is the Urdu word for freedom, and in these nine new essays, written over the last two years, Roy beckons readers to ponder its meaning in a world in which authoritarianism has crept to every corner of the globe, a world in which Modi—let alone Trump—seem stubbornly undefeatable. You will not find a polished riff here on the benefits of the shutdown. Roy watches and notes how the crisis was exploited before it was even a crisis, perhaps hastening its effects. That doesn’t mean it can’t still be a portal for us, however, she writes. “It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest—thus far—in the richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism to a juddering halt.” Where do we want to go from here? Is it really just simply getting that engine restarted? Was it really working for us she asks? –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Maxim Loskutoff, Ruthie Fear

Norton, September 1

Loskutoff is one of the most interesting and imaginative writers of the American West at work today. His 2018 debut, Come West and See, was a haunting and brutally beautiful collection of stories set in isolated parts of Montana, Idaho, and Oregon, and in his first novel he returns to rugged landscape of the Mountain West. Ruthie Fear is our eponymous heroine, raised in Montana’s imperiled Bitterroot Valley by a troubled single father, trying to find her place in a society shaped by violent men. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Eliot Weinberger, Angels and Saints

New Directions, September 1

In this remarkable book, Eliot Weinberger deploys his trademark deadpan equipoise to describe one of the world’s most startling beliefs (or phenomena): angels. Drawing from a wide variety of texts, from the Middle Ages and others much further back, and framed by illustrations of grid poems attributed to the eighteenth century Benedictine monk Hrabanus Maurus, Angels and Saints is a virtuoso demonstration of a writer getting out of the way of his subject’s fabulous detail. What to make of the fact that the word hierarchy was invented to describe angels? Or that the gravity-driven movement of blood in the body of a corpse might bring discolorations to the back in the shape of wings? Juxtaposition, as always in Weinberger’s work, does stark work here, too. In the second half, Weinberger tells many short biographies of the saints, from Columba from Ireland, to one pour soul, “a forest hermit…killed by a hunter who mistook him for a deer.” Angels, though speaking in tongues, are generally agreed to be incorporeal, to have almost no personality in the Bible (with the exception of Gabriel). The Saints however are all body—and in their flesh we see, perhaps, ourselves. Parts of this book feel as private as prayer; others like lamentation that there can be no meaning without pain. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Hari Kunzru, Red Pill

Knopf, September 1

Hari Kunzru’s White Tears is one of my favorite works of literary horror—part ghost story, part history of music, part meditation on race and privilege—so I can’t wait to read Red Pill, a novel that deals with the alt right and the commodification of state violence. I have no doubt Kunzru will handle both with terrifying deftness (and deft terrifyingness). –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Social Media Editor

Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Kurt Beals, Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces

New Directions, September 1

This collection of essays, memoirs and critical pieces forms an intellectual biography of Europe’s most history-obsessed writer. Beginning with her childhood in East Berlin in the early ‘60s and ‘70s, the book moves in concentric circles, from the intimate and understatedly moving – such as her essay on the bureaucracy of her mother’s death—to the moment History collides with her life and gives it a feeling of having been seen, such as the night the wall fell. In the aftermath, Erpenbeck remembers, there is a rush to suddenly move forward and erase the shameful past. “Recently, I opened the newspaper to find an obituary for my elementary school,” she writes. “Places always disappear in two stages,” she notes. “The first stage: the place is emptied out, grown over, it collapses . . . and then the second: the place is wiped out and replaced.”

In the book’s second and third sections, Erpenbeck moves on to culture and music, to Europe’s recent convulsions – yet there remains a feeling of bewilderment and curiosity in all of Erpbeck’s essays. Writing on her grandmother and great-grandmother’s past, on now unfashionable influences like Mann and E.T.A. Hoffman, this book is an attempt to resist these two-prongs of forgetting. It’s the sound of a powerful voice singing the past into the present’s melody. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, A Girl Is a Body of Water

Tin House, September 1

Best title award goes to this book, hands down. Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s novel centers on a young Ugandan girl named Kirabo, raised by women, none of whom are her mother, and who have specific ideas about how a girl should be. Kirabo tries to understand the conflicting forces within her: rebellion, submission, power, timidness, as she also tries to grapple with her histories, both the knowns and unknowns. We are taken on Kirabo’s journey as she attempts to fit all the pieces of herself together. –Julia Hass, Lit Hub Editorial Fellow

Elena Ferrante, tr. Ann Goldstein, The Lying Life of Adults

Europa, September 1

I mean, it’s the latest Elena Ferrante—we’re all going to anticipate it, and then we’re all going to read it. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Eula Biss, Having and Being Had

Riverhead, September 1

Owning a house is a litmus test to your values—one Eula Biss’ gives herself with a clear eye and braced heart in this strong new meditation on buying and owning in a society as a white woman where some people descend from Americans once considered property themselves.

The book starts small, with tiny questions that feel almost like answers to questions a friend might pose. Where did she buy the place and why? Who does the house work and which neighbors are let in the door?=

Composed in lyric bursts, more similar to her early book of poems, The Balloonists, than her last, On Immunity, this new work has turned the interrogative mode into a sound. “To afford something like paint,” she writes in one chapter, “for someone of my class, is to announce your values, most often, not your financial capacity.”

The accumulation of these pieces disassembles and reassembles a class the way it is built—through time: by turning over its assumptions, policy, and language in the hand. “Consume,” a social historian reminds her, “is from the Latin consumere, meaning “to seize or take over completely.’ A person might consume food or be consumed by rage. In its earliest usage, consumption always implied destruction.” This is an essential book for our out-of-control times of greed. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Evie Wyld, The Bass Rock

Pantheon, September 1

The latest novel from the Granta Best of Young British Novelist and author of All the Birds, Singing (which also had an incredible, refracted cover) concerns three women, separated by decades but bound by place: the titular Bass Rock, off the coast of Scotland, and by violence, perpetrated, of course, by men. Wyld can always be counted on for a haunting and propulsive experience, and I expect this book will be no different. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Joshua Bennett, Owed

Penguin Books, September 1

Joshua Bennett can do it all. A scholar, teacher, poet, critic, and performer, he’ll have two books out in 2020—the first of which, May’s Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man, you can sample here, and the second of which is his second collection of poetry, Owed, which is described as “a book with celebration at its center,” is sure to be an equally essential text. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, Likes

FSG, September 1

I’ve been a fan of Sarah Shun-lien Bynum since her genre-bending debut Madeleine Is Sleeping, which was a finalist for the National Book Award (soon to be reissued! Buy it.), so I’m obviously itching to pick up her latest collection, which Danzy Senna describes as “a cunning, electrifying work by one of the best writers of our times.” This is for fans of Aimee Bender, Karen Russell, Joy Williams, and all that is good. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Lucille Clifton, ed. Aracelis Girmay, How to Carry Water: Selected Poems

BOA Editions, September 8

Lucille Clifton’s vast gifts have been scattered among many collections, and one too big to carry. This fantastic selection, which brings together ten newly discovered poems, and the best of the rest, ought to give her a new life in the hand. Has there ever been such a tenderly caring poet—more various and vulnerable? Open to any page and there is Clifton’s huge, gentle, spoken voice, its awesome tonal shifts—the deep cackle and the way it could hoist sorrow. What Clifton inherited from Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks she turned into her own unique sound. One this book makes clear will be eternal. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Ruth Ware, One By One

Gallery/Scout Press, September 8

I adore all of Ruth Ware’s books, but one concerned with a group of coworkers trapped in a ski valet during a blizzard who slowly hack each other to pieces sounds tailor-made for the current pandemic. In One by One, the Silicon bros that make up the elite of a tech company head to Switzerland for a bonding trip that soon enough goes sour when a blizzard traps them in their luxurious abode with a sadistic killer, who may or may not be one of them. Hilarious, well plotted, and vintage Ware, this one is not to be missed. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

K-Ming Chang, Bestiary

One World, September 8

I am a sucker for novels by poets, and K-Ming Chang’s debut, which combines myth with family history, promises to reward my fixation. Young queer love, family secrets, and a girl who grows a tiger tale, all told by a language obsessive? Extremely sold. –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Social Media Editor

Tatiana Ryckman, The Ancestry of Objects

Deep Vellum Press, September 8

A dizzying story of girl meets boy, meets her all-encompassing desire, meets her equally fervent wish to end her life, meets the mysteries and ghosts that have circled her whole life, meets . . . so much more. The girl in question, an unnamed narrator, has wells of need and want at her core, for which the boy, David, is an unwitting receptacle. Told in fragments, and memories, and various voices, The Ancestry of Objects whirls the reader through the narrator’s many selves as our she attempts to reckon with the voids that we all contend with. –Julia Hass, Lit Hub Editorial Fellow

Claudia Rankine, Just Us

Graywolf, September 8

Like her beloved Citizen, Rankine’s latest is a riveting combination of poetry, essay, and image, incorporating both narrative and data, which here includes pie charts and excerpts from Twitter, snatches of conversation, art, as Rankine fact-checks herself, or proffers extratextual examples or context, on nearly every page. Rankine’s work is always essential, and this volume is no different: it is a rigorous examination of whiteness—but in particular, of the way white people understand (or do not understand) their own whiteness, or whiteness itself. Fans of Rankine will recognize the book’s opening, but here she goes much deeper and inserts much more of herself into the equation, and the result is disturbing, illuminating, and powerful. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Susie Yang, White Ivy

Simon & Schuster, September 8

White Ivy begins, “Ivy Lin was a thief but you would never know it to look at her.” What follows is a wonderfully plotted, page-turning novel about the lengths we will go to to get the life we want. Inside Susie Yang’s debut, you will find: a Chinese immigrant family, the lure of the alleged American Dream, something that feels like fate, the ghosts of people you used to know, a love triangle, and (bonus!) a kleptomaniac grandmother. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Sue Miller, Monogamy

Harper, September 8

A story of marriage, heartbreak, grief, and the question of fidelity: what more could we want? Graham and Annie were married for 30 years before Graham died suddenly; Annie had never once questioned whether he was faithful, until, after his death, she discovered evidence of his affairs. She is broken by the news, but also by the loss of her husband, and is left revolving around the questions of, how can you forgive someone who is no longer here? And can you ever really know anyone at all? –Julia Hass, Lit Hub Editorial Fellow

Kevin Young, ed., African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song

Library of America, September 8

We are living through a new heyday of African-American poetry, and this enormous book is a milestone of what actually has been an ongoing moment. Beginning in the 1780s with the great Phillis Wheatley, Young assembles three centuries of verse into discrete movements and periods, from bondage to what is being called “a furious flowering,” the explosion of the last ten years. Publication of the book ought to be an event.

No is better suited to the task of arranging than Young As a poet, scholar, director of the Schomburg center, anthologist and New Yorker editor, he hears and recognizes more sounds within poetry than just about any poetry person at work today. Breaking out Paul Laurence Dunbar and at James Weldon Johnson into their own period (with other poets), rather than seeing them primarily as precursors to the Harlem Renaissance, for example, he allows us to see their work as more than just a bridge. Furthermore, grouping Bob Kaufman and Gwendolyn Brooks in a period of their own—1937 to 1959—he shines a spotlight on that period’s class struggles.

Throughout, Young judiciously edits and resurrects, bringing back poets like Margaret Walker, the first Black poet to win the Yale Younger Poets Prize, and Shirley Anne Williams, not forgotten but somehow not fully appreciated, back into a little more light. A book this big allows all the vectors creating African American poetry to co-exist—from songs of slavery, to jazz to hip hop and modernism and collective work, none of them definitive, all deepening. What a glorious collection it is—full of voices of compassion and longing and celebration and mourning, it is a companion, a teaching touchtone, a mansion with many doors. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Jenny Bhatt, Each of Us Killers

7.13 Books, September 8

I’ve been waiting for Jenny Bhatt’s debut ever since she put together this excellent list of debut works of fiction by women over 40 for us in 2018; her collection, whose stories span the American midwest, India, and England, is already gilded with praise—Chaya Bhuvaneswar writes that this “collection works brilliantly both as an evocative amalgam of insightful observations about race, class, gender, aspirations, as well as on the sentence level,” which sounds like exactly what I want to read right now. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Sulaiman Addonia, Silence Is My Mother Tongue

Graywolf, September 8

In an East African refugee camp, teenage Saba and her brother Hagos—who refuses to speak—pass their days with others like them, forced to flee, fearful for their safety, and desperate to assemble some kind of stable realm. It wasn’t long ago Saba was simply a girl at school in a world which could be predicted. Here she takes on the role of protector and interpreter for her mute brother. Addonia is a poetic and compressed writer, he keeps the narrative eye focused close on the world Saba must navigate. Once, not long ago, Adonis was a similar position—having fled Eritrea to a refugee camp in Sudan, only to have to move again and go to school in Saudi Arabia. He came to England with his brother as a young man, where he learned English, the language in which he wrote this book. No he lives in Belgium and teaches writing to refugees in the position he was once in. Even more remarkable than Addonia’s journey is how he manages to put us inside Saba and her dilemma, rather than have us gaping at it from the outside—where it might be possible to turn away. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Sigrid Nunez, What Are You Going Through

Riverhead, September 8

From the National Book Award-winning author of The Friend comes a new novel about human connection and companionship. (Yes, if you are craving these things from wherever you are quarantined, take note!) The story begins with a recounting of various interactions, both minute and monumental (with an Airbnb host, with a childhood friend dying of cancer). Sigrid Nunez orchestrates a beautiful chorus of humanness here, and the novel asks a question we might all be thinking in these distant times: What does it mean to really be there for someone in times of hardship? –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Ross Gay, Be Holding: A Poem

University of Pittsburgh Press, September 8

Thanks to “The Last Dance,” Michael Jordan’s grace and poise are back to the front of mental highlight reels. But before him there was Dr. J, Julius Erving, whose airborne style of play and end-to-end wizardry made the sweat and squeak of a game played on hardwood seem like poetry. In his first collection since the National Book Critics Circle winning “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,” Ross Gay returns with a book length ode to the great Doctor—as he soars through the air in one of his greatest moves.

You do not need to have touched a basketball to appreciate how this book sings the man’s praises, how it describes the free movement of a body in space—“have you ever decided anything / in the air?” he asks, replaying Irving’s famous baseline scoop, part Frank Lloyd Wright, part of Michelangelo—the way he made of improvisation an art.

Pausing, beginning again, rewinding, Gay makes his own virtuosic loops from these three seconds, outward from that scoop, that game, the players there, to what was unfolding in America and still is, a country of people falling with no net. He asks himself, “I wonder if, no, / I wonder how, / I, too, am a docent / in the museum of black pain.” Gay watches the Doctor again ducking his head to avoid smashing it on the backboard, “the daily evasion of which is, / as you know, / a version of genius.” He remembers playing himself, body to body, “as though ascending a great staircase / made of air with joy.” This poem asserts its right to remember a moment and a person can be caught up in all these things, all at once, floating. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom

Knopf, September 8

The follow-up to Gyasi’s PEN/Hemingway Award-winning 2016 debut novel Homegoing is a psychologically complex portrait of a Ghanaian family in Alabama, focusing on Gifty, the lone member born in the States who, as part of her doctorate in neuroscience at Stanford, is attempting to see if she can alter the neural pathways leading to addiction and depression. Gifty’s struggles to reconcile her scientific pursuits (motivated by her brother’s death from a heroin overdose) with her family’s evangelical background. Gyasi’s debut was a marvel and this new work looks to be every bit as searing and emotionally resonant as its predecessor. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

André Leon Talley, The Chiffon Trenches: A Memoir

Ballantine, September 8

I am, in equal measure, fascinated and terrified by fashion people, so a juicy memoir about their bad behavior is exactly what I want to read. Add to that the fact that Andre Leon Talley, consummate fashion insider, has not been shy about his Anna Wintour criticism lately, and you have my undivided attention. –Jessie Gaynor, Lit Hub Social Media Editor

Daniel Mendelsohn, Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative and Fate

University of Virginia Press, September 8

This essay ought to become a beloved handbook for writing Annie Dillard’s Holy the Firm was in its time. Like Dillard, who was staring at infinity and the endlessness of human suffering, Mendelsohn, too, struggles with how to frame and scale stories in a world which chucks them into the oven of a hyper-active news cycle like coal. He comes up with a very old strategy, the ring method, as defined by Homer and others, in which patterns are repeated and deepened with movement and transformation. Mendelsohn goes one step further here, however, beyond defining it and describing it. He then performs it with a piece of fabulist writing which is a thrilling new mode in a career made of dramatic shifts in register, from fire breathing reviewer to meditative memoirist on desire (The Elusive Embrace, to mournful Sebaldian archivist in the face of the Holocaust (The Lost). In his last, book, The Odyssey, he wrote as a mensch-of-a-son giving his father one last tour through the classics “Danny” teaches at Bard. The ring structure allows him to be all things at once. The way this book feels so expansive in a space so small, you don’t even have to ask if the ring structure applies to things other than writing. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Marie Ndiaye, tr. Jordan Stump, That Time of Year

Two Lines, September 8

Marie Ndiaye’s That Time of Year has been described as a “literary horror story about power and assimilation” and praised by Laura van den Berg as a “shape-shifting masterpiece.” I’m sold. But in case you need a little more: Herman’s family is missing. They were on vacation, and now it is time to return home. Their normal life in the city is calling. The weather is turning. Despite his desperate attempts to find his wife and kids, Herman keeps hitting dead ends. And something seems to have shifted in the local community, something more sinister is taking root in their hospitality. Beautifully translated by Jordan Stump, That Time of Year is a gripping downward spiral into the uncanny. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Aimee Nezhukumatathil, World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks and Other Astonishments (illustrated by Fumi Nakamura)

Milkweed, September 8

As previously described: Should the wonderful David Attenborough ever retire, my hope is someone at BBC has read the work of Aimee Nezhukumatathil. What a great new naturalist of the airwaves she would make. As a poet, in books like Fishbone and Miracle Fruit, Nezhukumatathil has consistently reminded, through lucid description, that nature doesn’t need a metaphor. On its own it presents a wealth of wonder. “A snake heart can slide up and down the length of its body / when it needs to,” she writes in a poem from Oceanic, her most recent collection.

Now, in her first book of prose, Nezhukumatathil moves from water back to land, mostly, weaving a shadow memoir around catalpa plants, fireflies, saguaro and other plants, insects and animals. What a lovely book this is, gentle in its pacing, well-illustrated by Fumi Nakamura, and quietly subversive in the way he channels its gusts of joy. The child of two doctors, one from the Philippines, the other from India, as she moved around the country growing up, Nezhukumatathil was often the only brown girl in her classes.

World of Wonders doesn’t just gently reverse the gaze—to borrow a phrase from the novelist Aminatta Forna—applied to her, but refracts it too. “If a white girl tries to tell you what your brown skin can and cannot wear for makeup, just remember the smile of an axolotl.” And thus we come to know how a walking neotenic salamander will look right back at you and grin. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Alex Ross, Wagnerism: Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music

FSG, September 15

“Wagner’s effect on music was enormous,” writes Alex Ross in the opening of Wagnerism, his first book in over a decade, a brilliant cultural history of the German composer and his aftermath. “[B]ut it did not exceed that of Monteverdi, Bach or Beethoven. His effect on neighboring arts was, however, unprecedented, and it has not been equaled since, even in the popular arena.” Patiently, with a range which is breath-taking, and never bullied by the wonders of pop culture’s omnivorousness, this sumptuous book charts that ripples of Wagner’s influence—all those over-the-top tales of Gods, the psychosexual dramas, the booming doom complexes—into the work of poets (William Butler Yeats), novelists (Thomas Mann), artists (the Pre-Raphealites), and of course filmmakers (like Hitchcock and Francis Ford Coppola of “Apocalypse Now”). Even Bugs Bunny makes an appearance in this companionable book, which arrives just in time for what some days feels like the end of the world. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Micah Nemerever, These Violent Delights

Harper, September 15

This debut sounds extremely my shit: pitched as The Secret History meets Call Me By Your Name, it follows two college freshmen—Paul and Julian—who meet and soon develop a deep, dangerous obsession with one another. I don’t know what happens next, but I do know what happens in the second part of the line from Romeo and Juliet quoted in the title: “These violent delights have violent ends . . . ” I’m here for it. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

David Nasaw, The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War

Penguin Press, September 15

The best single book on Europe after 1945 is Tony Judt’s magisterial Postwar, but even in 880 pages, it didn’t have the room to address one of its key fact: that there were “some forty million in transit, moving within countries, between countries and into Europe from overseas” in the wake of the World War II. Here’s the book that does, and Nasaw—who won a Pulitzer for his biography of William Randolph Hearst—makes an important decision from the start. He begins in 1944, when millions were still in refugee camps, classified as POW, or were still being liberated from the Holocaust.

Beginning here allows him to study the catastrophic effect of some serious errors by the U.S. and others. In the melee of grappling with this multinational population, the Allied forces—through overwork, anti-Semitism, or just sheer lack of knowledge—allowed scores of Nazi sympathizers into the US. A juddering, contradictory policy on refugees also meant some people didn’t leave this purgatory until the 1950s. So many films of this period fade to tones of victory and congratulation—this book reminds that for some, the pain had just begun. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Alyssa Cole, When No One Is Watching

William Morrow, September 15

After a month of being too stressed out by the pandemic to finish anything, this is the book that got me going again and restored my faith in the power of books. It’s very Jordan Peele influenced, and it’s about a woman whose block is in the throes of gentrification—and her neighbors are mysteriously disappearing. The houses on the block are being sold at obscene prices, partially because the city is funding a new opioid recovery center in the old neighborhood hospital, shuttered for decades, and that adds insult to injury since the neighborhood didn’t get much help from the medical community during the crack cocaine epidemic. I can’t give too much away, but it was AWESOME, and I literally cheered at the end. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Susanna Clarke, Piranesi

Bloomsbury, September 15

I’ve been anticipating this one since it was announced last September: 15 years ago, Susanna Clarke published her genre-bending debut, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, which has now become a modern classic. Her long awaited sophomore novel, Piranesi is set in a new kind of dreamlike labyrinth: a strange, irreal house with infinite rooms and infinite statues and an ocean trapped within; the eponymous Piranesi lives there with The Other, and the two research A Great and Secret Knowledge. But what is beyond the infinite house? The wait is almost over. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Vigdis Hjorth, Long Live the Post Horn!

Verso, September 15

Before she became famous for taking Norwegian autofiction deeper into spaces formerly clouded by shame, Vigdis Hjorth was already beloved for her paper-cut wit and ability to make a story from small absurdities. Long Live the Post Horn! first published in 2012, is a classic example of this writing. The book follows a 35-year-old woman named Elinor who is having a crisis of existence, her diary so boring she can barely read it. When a coworker commits suicide, Elinor is thrust into a more active role at work on ginning up public support for privatization of postal services. What should be mind-numbing work turns into a new flowering, when she discovers the story of a long lost letter and the postal worker who wouldn’t give up on delivering it. Wrenching tenderness from the mouth of irony, Hjorth proves how major effects don’t always come from the heavy-foot pedals. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Rachel Howzell Hall, And Now She’s Gone

Forge, September 22

Rachel Howzell Hall goes into new territory with her upcoming mystery, where we meet the shy new girl at a private detective agency as she gets her first case—track down a stolen dog and return him to his owner, a pompous doctor. Problem is, the dog was stolen by the doctor’s ex-girlfriend who’s surprisingly good at vanishing, and as details of her case surface, Hall’s protagonist finds herself immersed in a wave of traumatic memories and new dangers that threaten to upset the careful new life she’s built for herself. And Now She’s Gone brings Hall’s trademark wit and slow-build suspense to the table once more, and it kept me turning the pages well into the night. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Christina Lamb, Our Bodies, Their Battlefield: What War Does to Women

Scribner, September 22

Civilian fatalities in wartime have climbed from 5 per cent at the turn of the century to more than 90 per cent in the wars of the 1990s and today. “Armed conflict kills and maims more children than soldiers,” noted Graça Machel, during her time as the UN Secretary-General’s Expert on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children. And women too suffer disproportionately as victims in war. The world now finds itself a place in which, perversely, the safest people in a war zone are likely to be the combatants. Christina Lamb’s Our Bodies, Their Battlefields: What War Does to Women, gives the phrase ‘women and children first’ a chilling, new meaning as she catalogues the violence done to women and girls in wars the world over. –Aminatta Forna, Lit Hub contributor

Eileen Myles, For Now

Yale University Press, September 22

Eileen Myles is back, thank god, and better than ever with their new writing-centered memoir, For Now (Why I Write). Yes, theoretically all memoirs by writers are inarguably pretty writing-centered, but this one tackles the big question, of why. This memoir, of course, wouldn’t be a Myles memoir without raucous vignettes of their young New York days, starting out as a writer, and stories of friends, lovers, and idols, because, after all, writing is about life, honoring it and being of it. This is something Myles has always managed to do: not only live life to the fullest, but also to go on and tell us all about it. –Julia Hass, Lit Hub Editorial Fellow

Susan Taubes, Divorcing

NYRB, September 22

Susan Sontag found the body of her friend, Susan Taubes, after Taubes committed suicide in 1969, soon after the publication of her sole novel, Divorcing. Critics at the time (mostly, snobbish men) panned the book, which tells of Sophie Blind, a woman who is getting a divorce from her husband and reflecting upon the many other split seams that defined her life, and the lives of her parents. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Laila Lalami, Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America

Pantheon, September 22

Laila Lalami’s exploration of belonging in America follows her experience as an immigrant from Morocco and her path to becoming a citizen, revealing much about the country’s troubled relationship with people whom it simultaneously values and pushes away. Her story is deeply personal and an essential testimony. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin, Climate Crisis and the Global Green Deal

Verso, September 22

One of the overarching fallacies behind resistance to a Green New Deal is that it’d wreck the economy. Not only is this morally bankrupt, Noam Chomsky points out in this brisk and lucid new book, cowritten with economist Robert Pollin, it’s also wrong. Stupidly wrong. In a little under two-hundred pages, they present a portrait of where the world is heading, and the necessity for retooling for a globe run by new energy sources, better habits and practices, and investment in industries that repair the earth rather than continue to treat it like a carcass to be picked at. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Smith Henderson and Jon Marc Smith, Make Them Cry

Ecco, September 22

Henderson’s first novel, Fourth of July Creek, was one of the most powerful debuts in recent memory. His follow-up, co-authored with Jon Marc Smith, is sure to have thriller readers feeling very encouraged, as he turns to a high-octane world of drug violence, dangerous borders, and government conspiracies. Make Them Cry is reminiscent of the best 1970s thrillers, but its secrets are of the moment, as a former prosecutor turned DEA agent gets wind of a cartel secret and heads to Mexico City to investigate. This is chiseled, adrenaline-fueled thriller writing at the highest level. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Juan Felipe Herrera, Every Day We Get More Illegal: Poems

City Lights, September 22

As previously described: Syncopated by a series of song-like addresses to a firefly on a road north, this dexterous and luminous new book by former US Poet Laureate is part Basho, part protest poem. Herrera’s roving eye captures all, from moments of ephemeral calm, to the way workers work—Herrera, the son of farm workers, laments how hard it has been for high culture to even regard people like them. The migrants who travel in shadows. Here as in other books, Herrera has stripped punctuation from many of the poems, leaving his lines to blow as if a holy wind moves through them. A prolific voice for justice, Herrera continues to see the world with love and sympathy, a goofy sort of humor, and a liberationist’s roving kind of care. These are warm poems for hard times. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Marilynne Robinson, Jack

FSG, September 29

She’s back! Much beloved Pulitzer Prize winner Marilynne Robinson is back, to guide us once more into the world of Gilead, Iowa. This new novel follows the son of a Presbytarian minister and his relationship with a high school teacher, also the child of a preacher. Jack is a love story, but it is also a story of power and guilt (like I said, a love story) and an interrogation of race and the hypocrisy in America. If you haven’t read the other novels in the series (Gilead, Home, and Lila), treat yourself to these contemporary classics. You have until the end of September to catch up. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Emily Gray Tedrowe, The Talented Miss Farwell

Custom House, September 29

Two things I love: female con artists, and novels about the art world. This book is both, and it also comes with high praise from Rebecca Makkai, who called its titular character “a Machiavellian marvel, a modern Becky Sharp, a character to root for despite your better judgment.” I would like to read about her, please. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

Ruth Stone, Bianca Stone, ed., The Essential Ruth Stone

Copper Canyon, September 29

Like her near contemporaries, Stanley Kunitz and Jack Gilbert, Ruth Stone’s rough honesty continues to seduce and haunt nearly a decade after her death. Over fifty years her poems steadily emerged with the grapple marks of wild things wrestled into form. It wasn’t always clear whether that wildness was life itself, or language. But an aesthetic appeared in Stone’s work which her granddaughter, the fabulous poet and visual artist Bianca Stone, has honed and enlarged in this terrific selection. Stone was a hilarious poet, a great chronicler of resistance to the thieves and pigs of state, and a mystic when she wanted to be. So much is on display here this is the kind of book that can kick off a renaissance, if you let it inside. If you’re hungry for poems which land square on the chest, full of hurt and feeling, but impatient with mere sentiment—look no further. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Namwali Serpell, Stranger Faces

Transit Books, September 29

Transit Books recently started a very cool project: the Undelivered Lectures Series. The Old Drift author Namwali Serpell has written the second one. Stranger Faces explores the idea of beauty, it interrogates the notion that the face is the way we understand humanity, and it forces us to confront what happens when we encounter something more unrecognizable. From this unique vantage point, these essays touch on technology, race, disability, death. You’ll never look at a face the same way again. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

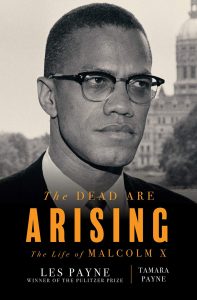

Les Payne with Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Rising: The Life of Malcolm X

Liveright, September 29

Thirty years ago, Les Payne—the Pulitzer Prize-winning former editor of Newsday, the same newspaper which created Robert Caro—set out to interview anyone who crossed paths with Malcolm X. Payne died two years ago, before he could complete his decades long biography of the Nebraska-born civil rights leader, but with the help of his daughter, Tamara Payne, we now have an indispensable portrait of Malcolm X’s life, from his Depression era childhood to his terrible death too early. Probing and well paced, full of new glimpses of the man becoming the man we still don’t quite know today, The Dead Are Rising does not read like a book unfinished, but rather a deliberately and beautifully written portrait. One sure to stand next to Manning Marble’s biography of ten years ago. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.