Lit Hub's Most Anticipated Books of 2019

What We're Looking Forward to, the First Half and Then Some

MAY

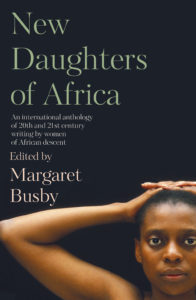

Margaret Busby, ed., New Daughters of Africa

Margaret Busby, ed., New Daughters of Africa

Amistad, May 7

Busby’s 1992 anthology curated a wave of cresting talent of the African diaspora, from Toni Cade Bambara and Maryse Conde and Dionne Brand to the already well known June Jordan and Ama Ata Aidoo. Twenty-five years later that wave has become a flood and this new volume showcases just how varied and geographically disparate the range of women writers with roots in Africa is today. And how many of these women are essentially transnational, from the British-Somali writer Nadifa Mohamed to the essayist and novelist Taiye Selasi, born of Nigerian and Ghanaian parents, raised in London and America, living today in Portugal. Featuring Aminatta Forna, Zadie Smith, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Andrea Levy and more, this book will be a cause for celebration and ought to be a textbook for years to come. (JF)

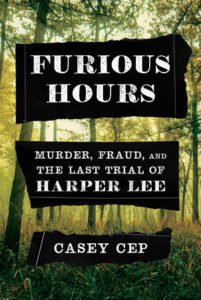

Casey Cep, Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee

Casey Cep, Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee

Knopf, May 7

Did you know that after publishing To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee spent a year reporting and researching for a true crime novel (yes, a la In Cold Blood) about an Alabama serial killer? Me neither, but Cep did, and this book tells the whole story—and gives a window into the life and obsession of one of America’s most beloved and mysterious writers. (ET)

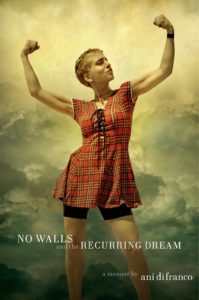

Ani DiFranco, No Walls and the Recurring Dream

Ani DiFranco, No Walls and the Recurring Dream

Viking, May 7

This is a memoir from Ani DiFranco. If this book is meant for you, you are already screaming right now. If not, it’s fine. You can’t go back. Just keep scrolling. (DM)

Aleksandar Hemon, My Parents/This Does Not Belong to You

Aleksandar Hemon, My Parents/This Does Not Belong to You

MCD x FSG Originals, May 7

With his departure of Chicago for Princeton, it feels like the re-narrativization of Aleksandar Hemon’s self has come to the end of one vivid orbit. These two extraordinary books form the comet tail of that circuit. On one hand My Parents chronicles the lives and histories of his beloved parents, their flight from Sarajevo and reconstruction of a home in Canada. It showcases Hemon’s great gift for carrying other people’s stories. On the other hand This Doesn’t Belong to You returns to the city of Hemon’s youth and beautifully depicts the awakening of his consciousness in language. These pieces, which cycle back to when the MacArthur winner was eight years old, are strange, dark lyrics to the feral qualities of childhood, some of them closer to poetry than prose. They feature some of his most shatteringly beautiful sentences yet. Together these two books present a powerful portrait of the forces which make us: the language we learn, which allows us to catch time in our hands; and the stories we inherit and witness, which teach us the stakes. Here is how memory’s mosaic, born out of love, becomes something almost holy. (JF)

Binnie Kirshenbaum, Rabbits for Food

Binnie Kirshenbaum, Rabbits for Food

Soho Press, May 7

If 2018 has prepared me for anything, it’s how to enjoy a novel about a nervous breakdown. During the forced reverie of New Year’s Eve, Kirshenbaum’s clinically depressed writer protagonist completely unravels and ends up in a psych ward. Instead of accepting treatment, she writes her way through the experience and her grief, and I could not be more excited for Kirshenbaum’s first novel in ten years (EF)

Chia-Chia Lin, The Unpassing

Chia-Chia Lin, The Unpassing

FSG, May 7

Chia-Chia Lin’s debut novel paints a devastating portrait of a family waking up from the American dream. This hard-working immigrant family from Taiwan struggles to make ends meet in Anchorage. Tragedy strikes when the children are infected with meningitis—and one of them doesn’t survive. The Unpassing is a moving story about grief, guilt, growing apart, and finding home. (KY)

Joanne Ramos, The Farm

Joanne Ramos, The Farm

Random House, May 7

Imagine the most luxurious Hudson Valley retreat: organic food, daily massages, personal trainers, beautiful sights, and all for free. Actually they pay you—if you submit to their rules, do not leave the premises, and leave after nine months having produced a perfect baby. Of course our heroine is a woman who wants to break all the rules—Jane, fearing for her child, is desperate to leave The Farm, but terrified of what will happen if she does. A chilling and all-too plausible vision of the future. (ET)

Rebecca Solnit, ill. Arthur Rackham, Cinderella Liberator

Rebecca Solnit, ill. Arthur Rackham, Cinderella Liberator

Haymarket, May 7

Rebecca Solnit is so good at demolishing broken narratives we tend to forget she’s equally skilled at raising new ones from their rubble. Essay by essay, as she’s done this in pieces about women, landscape, community action and the West, she’s enlarged the possibilities of what wasn’t working to begin with—often using genres we don’t typically associate as being in the wheelhouse of a political essayist. In one essay for this site, for example, she used the tones of a fairy tale to tell of Trump’s isolation; in another, riffing on a species of masculinity unwilling to change, she drew on the syntax of biological studies. So here comes Solnit in the open court with the yarn of Cinderella. What do you think she would do once she got the classic folk tale in her hands? It would have been so easy to make this a new story of revenge. Solnit’s version turns out to be a parable of intergenerational power sharing. Her Cinderella indeed is poor and also has a wicked stepmother. Like the Grimm’s edition, she’s also rescued by a fairy godmother, and loses a shoe. Upon coming home, though, Solnit’s heroine can’t help but marvel at the fairy godmother’s power. You turned mice into horses and a rat into a footman, she asks, what else or who else can we liberate? And off they go taking this miraculous wand and turning it to good, even freeing up the prince, who never really wanted to be a prince after-all. This is an inspired take on this time-worn tale. Someone smart will turn Solnit’s new version into a blockbuster film and Liberator will forever after be attached to the little girl’s name, not Disney. (JF)

Ted Chiang, Exhalation: Stories

Ted Chiang, Exhalation: Stories

Knopf, May 8

Early in May there’s a high likelihood a book of short stories will shoot up onto the New York Times bestseller list. And unless you’ve been an avid reader of the journals “Subterranean online” and “e-flux,” or happened to catch the Best American Short Stories edited by Junot Díaz, chances are the name Ted Chiang will be new to you. After Exhalation it probably won’t be. Seventeen years after the publication of his debut collection, Chiang is back with and it’s clear he’s now the Alice Munro of science fiction. These nine long stories run the gamut in scenarios from a world where everyone is lifelogging to a heartbreaking tale of software developers trying to rescue digital animals from increasingly utilitarian corporate greed. What they share is a profound concern with the impact of a technology on civilization and the way culture and belief collide depending on where we grow up. Chiang is a master of different modes of fiction. One story begins in Baghdad in the long ago past where a gate allows travelers to glimpse their future selves. An air-driven mechanical being narrates the title story, and it concludes at an odd destination for science fiction in our age: hopefulness. “It cheers me to imagine that the air that once powered me could power others,” it says. Chances are these tales will project readers straight back to Chiang’s first collection for more mind-expanding work. (JF)

Kathleen Alcott, America Was Hard to Find

Kathleen Alcott, America Was Hard to Find

Ecco, May 14

I love intricate alternate histories, and I especially love them when they’re penned by authors with that rare ability to combine vivid, dazzling prose with sensitive and nuanced character building. Kathleen Alcott is one of those writers, and that’s why I’m especially excited to read her new novel, America Was Hard to Find—a reimagining of the Cold War era focusing on an activist and an astronaut who, after a short-lived affair, go their separate ways and become heroes to different sides of the political spectrum of 1970s America. (DS)

Hybrida, Tina Chang

Hybrida, Tina Chang

W. W. Norton, May 14

Tina Chang’s third collection moves like a tour-de-force of fury and love. Further proof that poetry’s power to negotiate polarized space explains why it’s so potent now. At the hub of Chang’s project lies a robust reclamation of motherhood as a hybrid form. To do this she deploys multiple poetic modes, from the zuhitsu to ghazals, which spoke outward from the book’s centerpiece, wherein she writes: “Vocabulary is the future we’ve all been waiting for.” Around the collection’s ancient title word Chang fashions a new definition: one that puts hybridity at the heart of American existence. She sings lyrics to her young children, as if giving them permission to be more than their pasts — while warning them not to forget where they come from. “Revolutionary Kiss” traces the threads of history which led to the improbable miracle of her boy, born of Haitian and Taiwanese upheavals into Brooklyn today. In some poems, Chang wends compassionately around the figures of Michael Brown and Noemi Álvarez Quillay, showing how her own concerns—for safety, against racial bias in schools—are questions of life and death for so many mothers. In other poems, like “Portraits,” she gazes into art works—such as Kara Walker’s “Woman Beneath a Woman”—and shifts sideways into abstract space. For all the intimacy of Chang’s lyrics, a number of which ought to be anthologized into the next century, it’s in these poems where she forges some of her finest lines, such as: “If I could walk out from under this thunder/there would be such air.” Who hasn’t made a tent of care above a child’s head in stormy times and felt the same? (JF)

Fernando A. Flores, Tears of the Trufflepig

Fernando A. Flores, Tears of the Trufflepig

MCD x FSG Originals, May 14

One of FSG Originals’ distinctive, beautifully designed offerings, Fernando A. Flores’ debut novel Tears of the Trufflepig is an oddball, picaresque ode to Mexican myth, life on the border, as well as an investigation of loss and a warning against the one percent’s determination to speed up society’s decline. Tears of the Trufflepig takes place in a near-future South Texas where narcotics are legal and the new contraband is Olmec artifacts, shrunken indigenous heads, and “filtered” animals brought back from extinction to feed and amuse the wealthy. If that isn’t enough to draw you in, Trufflepig also contains legends of a long-disappeared indigenous tribe and their object of worship, the curiously-named Trufflepig. It seems that Trufflepig could be one of the most simultaneously wild and sobering books you’ll read in 2019. I’m looking forward to finding out for myself. (MK)

Adam Foulds, Dream Sequence

Adam Foulds, Dream Sequence

FSG, May 14

Henry is a TV actor, who does fine on a show that has a core group of obsessive fans, but who longs for bigger and better things; Kristin, recently divorced, doesn’t think there is anyone bigger or better. than Henry She’s sure the two of them are meant to be together, and decides to fly to London to make it happen. Turns out celebrity isn’t always as great as we think it is. (ET)

Emily Nussbaum, I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution

Emily Nussbaum, I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution

Random House, May 14

A very exciting book of new and collected essays from your favorite TV critic and mine. (ET)

Max Porter, Lanny

Max Porter, Lanny

Graywolf, May 14

Porter’s second novel, after the poetic Grief is the Thing with Feathers, concerns an English town near London, where Dead Papa Toothwort has recently woken up from a nap. He has woken up, and now he is waiting for Lanny. Another fabulist feat from Porter. (ET)

Xuan Juliana Wang, Home Remedies

Xuan Juliana Wang, Home Remedies

Hogarth, May 14, 2019

Wang’s excellent collection is filled with memorable characters, unusual jobs, and the juxtaposition of modern life and cultural heritage. You might have read her brilliant essay on The Cut this past summer, which you can read as an autobiographical introduction to this remarkable debut. (EF)

Julia Phillips, Disappearing Earth

Julia Phillips, Disappearing Earth

Knopf, May 21

Fulbright fellow Julia Phillips’s debut begins with the abduction of two girls from a remote Russian peninsula—and goes on to tell the stories of several of the women in their community and how they are affected by the loss in the months afterwards.

John Waters, Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder

John Waters, Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder

FSG, June 4

Honestly, I thought I couldn’t love John Waters any more, and then I read the subtitle of this book. Another volume of wisdom and wit from our transgressive weirdo sophisticated smut king is always welcome. (ET)

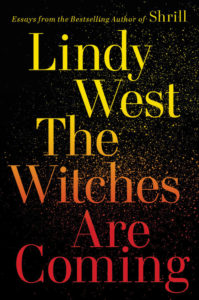

Lindy West, The Witches Are Coming

Lindy West, The Witches Are Coming

Hachette, May 28

“Yes, This Is a Witch Hunt. I’m a Witch and I’m Hunting You.” This op-ed by Lindy West for The New York Times last October was a welcome look at what happens when society stops overlooking the behavior of some predatory men. Now, with a mix of incisive wit and sharp culture criticism, West’s new book promises to untangle the systems of power that have allowed American culture to disempower women and people of color while propping up misogyny, racism, and other forces that propelled our current president to the White House. (CS)

Saskia Vogel, Permission

Saskia Vogel, Permission

Coach House, May 29

If Joan Didion had written about the BDSM community in LA it may have felt a bit like Permission, Saskia Vogel’s evocative debut novel. When Echo’s father dies in a freak accident, grief pulls her under like a rip curl into a world of art models, dominatrixes and sex workers. Many of them are part timers hoping for a break into a Hollywood’s dream machine. Step by step Echo doesn’t just watch, but there are risks. Vogel is deeply perceptive of how a desire to be seen can grow out of acute loss, and how friendships made in enclosed worlds waver due to the way shame can dart in. Like Didion, Vogel is all about atmosphere and can burnish a sentence down to a Stingray’s tail bulb’s perfection. Didion was a tourist though in some of the worlds she explored, like Salvador or a murder scene. On occasion, it was hard for her not to sneer. Vogel only loves her characters, even when they’re making bad decisions, sometimes to an almost utopian degree. For the past five years the LA native has been a big reason why some of Sweden’s best young writers are finally making it into English, novelists like Lina Wolff, Lena Andersson, and Karolina Ramquist. Many of them feminists interested in the warp of sex and love. There’s a quest in all these writers to grapple with the shape of society and what it could be if certain assumptions could be changed. Here with her own work Vogel starts more modestly, but no less ambitiously; she just shows us what is there, barely underground, and by treating it with dignity rather luridness, gives us permission to visit. (JF)

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.