Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2019, Part 2

What We're Looking Forward to, July through December

*

NOVEMBER

Carmen Maria Machado, In the Dream House

Graywolf, November 5

Like pretty much everyone else I know who reads books, I’ve been obsessed with Carmen Maria Machado since her 2017 short story collection Her Body and Other Parties (well, actually before that, but this is neither here nor there). Her sentences are like spells; I don’t know how else to say it. Her second book is a memoir about surviving an abusive relationship, the chapters divided by narrative tropes, themes, and forms—Dream House as Picaresque, Dream House as Mystical Pregnancy, Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure—and it is weird, innovative, and affecting to the core.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Liska Jacobs, The Worst Kind of Want

MCD, November 5

A literary noir about a fortysomething woman who travels to Rome after a long spell of serving as her mother’s caregiver, ostensibly to keep an eye on her teenage niece, this novel sounds dark, fascinating, and like any noir worth its salt, sexy. According to its publisher’s page, The Worst Kind of Want has “the sharp-edged insight of Ottessa Moshfegh and the taut seduction of Patricia Highsmith,” and if that doesn’t sell you then we have nothing more to say to one another.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

H. J. Golakai, The Score

Cassava Republic Press, November 5

Golukai’s reporter-activist heroine Vee Johnson returns for her second investigation, as she and her partner stumble upon a murder in the midst of what was meant to be a punishingly boring assignment reviewing a dusty tourist lodge in the middle of nowhere. As the journalists investigate, they’re drawn into an intricate web of corruption, murder, and dog-walking. Cassava Republic is one of the coolest indie international presses around, and I read all their releases religiously.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Susannah Cahalan, The Great Pretender

Grand Central, November 5

In the 1970s, Stanford psychologist David Rosenhan and seven other “normal” people went undercover into mental health institutions across the country to test the validity of diagnosis and treatment. The result was groundbreaking; their findings closed down whole facilities. To this day, their experiment is still often referenced as a milestone in our understanding of “madness.” But is it the whole story? Susannah Cahalan digs deeper, and brings the conversation David Rosenhan and his colleagues started to today’s mental health debates.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Jenny Slate, Little Weirds

Little, Brown, November 5

I am just going to leave the official description of this book here, and you can decide whether it appeals:

Hello! I looked into my brain and found a book. Here it is. Inside you will find:

The smell of honeysuckle

Heartbreak

A French-kissing rabbit

A haunted house

Death

A vagina singing sad old songs

Young geraniums in an ancient castle

Birth

A dog who appears in dreams as a spiritual guide

Divorce

Electromagnetic energy fields

Emotional horniness

The ghost of a sea captain

And more

I hope you enjoy these little weirds.

Love,

Jenny Slate

I think you’ve got the idea.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Johannes Anyuru, tr. Saskia Vogel, They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears

Two Lines, November 5

One of the impoverishments of most terrorist attack fiction is how hard such novels find it to imagine anything else. Anger, radicalization, brutality, shock and the aftermath of trauma: it often feels too much like a replay of what television has already shown us. This new novel by Swedish writer Johannes Anyuru departs fantastically from this script. It begins with an assault on a comic book store during an event by a cartoonist who has made jokes at the Prophet’s expense, but where it goes from there is strange, magical, and one of the first books to emerge out of our modern time to touch terrorism the way Vonnegut did war. Anyuru doesn’t shock the mind, but rather force us to ask new questions about what being a spectator truly means.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Kevin Wilson, Nothing to See Here

Ecco, November 5

I can always count on Kevin Wilson to a) make me laugh and b) make me feel things. His newest novel, in which a woman is tasked with taking care of two young children—who, not for nothing, tend to burst into flames when agitated—is certain to keep the trend going.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Erin Morgenstern, The Starless Sea

Doubleday, November 5

I was at the American Library Association conference in DC a week ago and the line to acquire an early copy of this one—a sweeping love story set in a secret underground world of pirates, painters, lovers, liars, and magical ships—was so long that I just assumed there was some wonderful new drug or open bar at the end of it. If that isn’t a good omen for this follow-up to Morgenstern’s beloved 2011 fantasy debut, The Night Circus, I don’t know what is.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Mark Z. Danielewski, The Little Blue Kite

Pantheon, November 5

I’m going to level with you: I have no idea what this book is about. All I can find is an enigmatic description, a cover, a category (literary fiction) and a length (96 pages). Other than that, who knows? But it’s Danielewski, so I thought you might like to know. Here’s the description:

We all have fears, but if we can’t face the small ones how will we face the big ones? Kai is afraid to fly a little blue kite. But Kai is also very, very brave, and overcoming this small fear will lead him on a great adventure.

Remember: all great adventures start with one little moment. You know the one. It’s like a gentle breeze whispering in your ear what you already know by heart:

not even the sky is the limit . . .

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Charles Wright, Oblivion Banjo

FSG, November 5

For decades Charles Wright has been America’s backwood Buddhist, its metaphysical gardener, its lore collector, a most cosmopolitan local. He’s never donned a farmer’s costume or heckled the trees without dignity. He simply listens, taking in what the land says without speaking. As a poet he creates a similar effect, whether working in a sestet or a sonnet, or in the long, wending lines of his 1995 volume, Chickamauga, Wright sounds the same: Like a poet looking inward and outward at the same time. The measure of his breath is timed for trance states and revelation, but it’s never a mist machine. A Tennessean by birth and longstanding Virginia by residence, he knows too much blood was spilled across the South to go looking for transcendent relief. So he listens to the ghosts, even the culture around him hasn’t. “The grill net of history will pluck us soon enough,” he once wrote. This book collects all of his work as if that time is near.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Margaret Wilkerson Sexton, The Revisioners

Counterpoint, November 5

Sexton’s follow-up to her National Book Award-nominated debut, A Kind of Freedom, tackles generational legacies, the echoes of history, and strength of bonds between women. R. O. Kwon called it “a time-bending epic about family, desire, strength, and terror, as well as the possibly supernatural power of the stories we tell ourselves,” which is good enough for me.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Fintan O’Toole, The Politics of Pain: Postwar England and the Rise of Nationalism

Liveright, November 5

Fintan O’Toole is one of Ireland’s sharpest and most compassionate political and social commentators (not to mention our foremost theater critic) and his analysis of the national obsessions, psychological hang-ups, and colonialism-derived paranoias that led to Brexit is an absolute must-read for anyone looking to understand why exactly Britain voted to self-immolate three years ago.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Virginie Despentes, tr. Frank Wynne, Vernon Subutex 1

FSG Originals, November 5

Throughout Europe, Despentes’ gritty trilogy of novels about a down-on-his-luck Parisian record store owner are front and center at most bookstores. At last volume one will bolt from its gate in America this fall, unleashing Despentes’ terrifying vision of 21st-century Paris. If you haven’t seen her film, Base-Moi, or read her essays on gender and porn or power, hang on tight. Hers is a world gusting on mountains of coke, dirty couches, never-ending parties hosted by sentimental stock-brokers, and a teetering sense that the phantasmagoria of modern life is so poisonous it may not be survived. Despentes’ unnerving ability to render gargoyles of humanity into believable—sometimes even touching—characters keeps these books’ hooks in you, even if you try to pull away.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Tommy Pico, Feed

Tin House, November 5

Releasing his fourth book of poetry in as many years, Tommy Pico rounds out the Teebs saga with Feed, a sprawling love letter to himself and the universe. Teebs seeks to feed himself emotionally by grappling with the idea of reconciliation, and stomach-ly by grappling with mac and cheese. Hilarious, inventive, and insightful, it’s Feed like your Twitter feed, or like a setup and the punchline is your feelings.

–Kevin Chau, Editorial Fellow

Jorge Comensal, tr. Charlotte Whittle, The Mutations

FSG, November 12

I firmly believe that all tragedies benefit from comedy (and vice versa). Jorge Comensal’s debut novel is a comedy about cancer of the tongue, after which the Ramón, the afflicted protagonist—a “successful lawyer and militant atheist”—can no longer speak. One review called it “hilarious and funereal,” which is what I hope for from all books, as well as from my own funeral.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

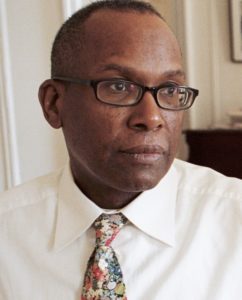

Darryl Pinckney, Busted in New York and Other Essays

FSG, November 12

“White supremacy isn’t back,” Pinckney tells us in this book of 25 essays about black intellectual, social, and personal history in America and beyond, “it never went away.” Pinckney’s essays tackle Ferguson, James Baldwin, Kara Walker, Moonlight, the Black Panther Party and more with sharp intelligence and a keen historical sensibility. As Zadie Smith writes in the introduction to the book: “How lucky we are to have Darryl Pinckney who, without rancor, without insult, has, all these years, been taking down our various songs, examining them with love and care, and bringing them back from the past, like a Sankofa bird, for our present examination. These days Sankofas like Darryl are rare. Treasure him!”

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

D. H. Lawrence, ed. Geoff Dyer, The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays

NYRB, November 12

The son of a coal miner father and a mother who worked in lace-making industries, David Herbert Lawrence has become such a monolith it’s sometimes hard to seem him in plain sight. How a man so frail, who spent so much time restlessly moving across Europe and the globe, and who died at just age 44, managed to produce more than fifty volumes of poetry, drama, and fiction in such a short life—upending, for better or worse, how sex was written about—remains a marvel. He was also, clearly, a prolific essayist, writing on everything from porcupines to government to the morality questions of literature. Late in his life, he was often doing it at great speed, alongside reviewing, for money, still with a lot of style. Here Geoff Dyer, one of literature’s slyly prolific writers himself, and author of the funniest book on Lawrence to date, edits and selects what ought to be seen into this compelling, not too fat volume.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Wole Soyinka, Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions

Yale University Press, November 12

Playwright, poet, essayist, and Nobel laureate Soyinka is also an avid art collector, and this book of essays is a personal look at his journeys in the art world and his impressions of the complex position of African art—making it, collecting it, exhibiting it—today, and how that relates to its history and tradition.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Nicola Gardini, Long Live Latin

FSG, November 12

As a failed Classics major, I still have a soft spot for all things Greek and Latin-adjacent. In Long Live Latin, novelist and Oxford professor Nicola Gardini makes a case for the “dead” language he loves. I have found Classics professors to be some of the most passionate people on earth, so I expect this book will have me digging out my Wheelock’s Latin and making flashcards for at least a week or two. I’m also excited by the fact that the books translator, Todd Portnowitz, has previously translated several collections of poetry, which seems very promising for this book’s linguistic potential (pun intended? I don’t even know anymore).

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Lydia Davis, Essays: One

FSG, November 12

Lydia Davis’ Varieties of Disturbance changed the shape of storytelling for me. It is one of the few books I return to time and time again, so I’m excited to see what happens when she turns her wit and carefully chosen language into nonfiction. Essays: One is a collection of five decades’ worth of essays, lectures, and wisdom.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Vladimir Nabokov, Think, Write, Speak: Uncollected Essays, Reviews, Interviews, and Letters to the Editor

Knopf, November 13

To be perfectly honest, I can’t imagine what’s in here. After all, we’ve all been fully obsessed with Nabokov for years, and after Strong Opinions, what could be next? His grocery lists? I mean, let’s get real, there is no world in which it was Vlad and not Vera who wrote the grocery lists, but I guess what I’m trying to say is: it doesn’t really matter what’s in here, because I am going to read it. Such is the power of Nabokov.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Elena Ferrante, Incidental Inventions

Europa, November 19

Yes, I know I could have read Ferrante’s year of op-eds in The Guardian, but I didn’t. So I’m going to read them in this nice little edition that Europa Press put together, because it’s Elena Ferrante and she’s great.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Burhan Sönmez, tr. Umit Hussein, Labyrinth

Other Press, November 19

As this book opens, a blues singer attempts to take his life by jumping five-hundred feet off a bridge into the Bosphorus. He survives but his memory is shattered—he knows the last Sultan has died, but the rest is a maze. This short, elliptical novel by the author of Istanbul, Istanbul follows him into its pathways, conjuring the ineluctable entanglement of place and person.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Nina MacLaughlin, Wake, Siren

FSG Originals, November 19

It’s been a long time coming. Women are standing at the helm, holding the mic, wielding the pen now. But what about the stories of old? What have we missed in the telling of those tales? In Nina MacLaughlin’s Wake, Siren, we venture back into myth, to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, to hear from the seductresses, the nymphs, and the goddesses. Finally.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Dexter Palmer, Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen

Pantheon, November 19

I’ll admit it: I was anticipating this novel based on the title alone—and then I saw the cover, and then I found out that it was based on the true story of a woman in 1726 in Godalming, England, who, it seemed, kept giving birth to dead rabbits. Of course it was eventually proven to be a hoax, but still, I definitely need to read a novel about it. Maybe I’ll rewatch The Favorite after I’m done reading.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Fleur Jaeggy, tr. Tim Parks, Sweet Days of Discipline

New Directions, November 26

Listen: if you have not read this exceptional novel, please take the opportunity of its reissue (with a perfect new cover by Oliver Munday) to do so. It is a slim novel, glorious, acerbic, and sad, about one young girl’s obsession with another at a Swiss boarding school. I have never gasped so much in sheer literary joy as while reading this novel; just trust me.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor