Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2019, Part 2

What We're Looking Forward to, July through December

*

SEPTEMBER

Salman Rushdie, Quichotte

Random House, September 3

Rushdie’s latest novel is a literary satire—a picaresque inspired by (and working in homage to) Cervantes’ Don Quixote—in which a mediocre thriller writer assumes a gallant identity and sets off across the country with his imaginary son Sancho to win the heart of a TV actress. Hilarious by all accounts.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Walter Mosley, Elements of Fiction

Grove Press, September 3

Mosley, an icon of contemporary crime fiction, brings his many insights on craft and storytelling to bear in this instructive and illuminating new guide. Elements of Fiction is clearly the work of an artist who has spent a lifetime thinking about what makes a story powerful, how to tell it, and how to hone and improve your craft.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Etgar Keret, tr. Sondra Silverston, Nathan Englander, Jessica Cohen, Miriam Shlesinger, Yardenne Greenspan, Fly Already

Riverhead, September 3

Like Lydia Davis, Etgar Keret has written stories of such singular diminutive style it took the culture a few years to realize: this is not a novelty act. This is the work of a genius, and he can pack more comedy and heartache into a single tale than just about any writer alive. A new book is cause for celebration.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Nick Flynn, I Will Destroy You

Graywolf, September 3

Nick Flynn’s poems are gritty and emotional, grim and loving, funny and also about death and addiction and grief. I can’t wait to sleep with this volume under my pillow.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Monique Truong, The Sweetest Fruits

Viking, September 3

From the acclaimed author of The Book of Salt, the diaries of Gertrude Stein’s fictional queer Vietnamese-French personal chef, comes another novelization of a famous writer’s life. Three of Lafcadio Hearn’s lovers narrate The Sweetest Fruits, each from a different country—Greece, the US, and Japan—and each wielding a distinctive voice and talent for storytelling. In The Sweetest Fruits, Monique Truong does what she does best, painting a vivid portrait of privilege, restlessness, and tenacity through the conflicting experiences of characters grappling with their senses of love, family, and home.

–Kevin Chau, Editorial Fellow

Rebecca Solnit, Whose Story Is This?: Old Conflicts, New Chapters

Haymarket, September 3

In her latest book of essays, some of which appeared in this space, Rebecca Solnit continues to question the terms of public debate, highlighting broken narratives and reinstating context in the culture of no context. As ever, the range of forms Solnit calls upon, let alone her varieties of tone and language, is simply awesome. Also, as in her books A Paradise Built in Hell and Hope in the Dark, she can be surprisingly, comfortingly sanguine in what can seem like times of flagrant corruption, revitalized hatreds, sexism, and climate suicide. There are no dirges here, no tone-poems to the apocalypse: here, she shows, in one essay after another, is how you unpick the tangle unreason has made for us. For a long time, some of us feared that the torch-light of Solnit’s voluminous mind would only be recognized in the future. That gap no longer exists, and it has happily closed just when she’s at the height of her powers and needed most.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

David Koepp, Cold Storage

Ecco, September 3

David Koepp, a screenwriter who wrote the original Mission: Impossible movie as well as, um, Jurassic Park and also Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull (not his best), sold his debut novel to Ecco in 2018 for “a significant seven figures.” Obviously, there’s already a movie in the works, and why not? It’s a climate-change-tinged disaster thriller in which rising temperatures activate a long-buried fungus poised to destroy humanity—unless our heroes can stop it. I’m already biting my nails.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Lara Prescott, The Secrets We Kept

Knopf, September 3

Prescott’s debut is an epic of passion, daring, and art. Part spy thriller, part intimate drama, The Secrets We Kept is the story of two women working for the government during tense days in the Cold War, enlisted for an audacious plot: smuggling Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago out of the Soviet Union and into worldwide publication.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Tash Aw, We, the Survivors

FSG, September 3

In We, the Survivors, a man named Ah Hock recounts his life to a well-off American-educated journalist, from his childhood in a small Malaysian village, to his various jobs in restaurants and fish farms, to the murder of a Bangladeshi immigrant that landed him in prison. Navigating the tumultuous political landscape of Malaysia through the experiences of an impoverished laborer who nevertheless benefits from the combination of racial privilege and sheer luck, Tash Aw has crafted a complex, tense story of power, violence, loss, and hope.

–Kevin Chau, Editorial Fellow

Naja Marie Aidt, tr. Denise Newman, When Death Takes Something from You Give it Back

Coffee House, September 3

This beautiful, exquisitely made memoir is Didion 4.0: a shattering recounting of how the death of Aidt’s son in a freak accident knocked the author sideways, compelling a whole-scale reorganization of what she once knew. This is a book about more than shock, grief and mourning, though. Drawing on the work of poets Anne Carson, Inger Chirstensen and others, it’s a meditation on time and the way our narration of what happens during life sieves through a slippery gear—our selves—how consciousness is the sound of trying to get it turning again.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

William Kent Kreuger, This Tender Land

Atria, September 3

Krueger’s latest novel is more epic adventure than traditional thriller, but the author’s many ardent fans will be no less anxious for its fall release, as Krueger takes on a grand and ambitious story about four orphans traveling during the Great Depression after breaking free from the Lincoln School for Native American children. This Tender Land is a moving portrait of a time and place receding from the collective memory, but leaving its mark on the heart of what the nation has become.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Angie Cruz, Dominicana

Flatiron, September 3

Ana Cancion comes to the US as the wife of Juan Ruiz—but theirs soon becomes an unhappy marriage that leaves her lonely in a city where she knows no one. After her husband leaves, his younger brother shows her a glimpse of what her life could be in New York.

–Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Jennine Capó Crucet, My Time Among the Whites

Picador, September 3

Aside from being smart and fearless when it comes to writing about her experience (or lack thereof) of the so-called American Dream, Jennine Capó Crucet is also… funny. Of course, a sense of humor is a necessary survival mechanism when navigating America’s hypocritical self-mythologizing, as you quickly discover that laudatory boot-strap immigrant narratives are generally reserved for the lily white Irish ancestor. Capó Crucet’s essays of her Cuban-American experience—as it occurs across the country, from Disney World to Nebraska—assert new narratives of what it means to come to this country, at once hopeful and dispiriting, infuriating and comic.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Dina Nayeri, The Ungrateful Refugee

Catapult, September 3

What is it like to be a refugee? Expanding on her fantastic Guardian article, Nayeri describes fleeing Iran as a child and living in an Italian hotel before being granted asylum in America. Weaved together with the stories of more recent asylum seekers Nayeri confronts notions like “the swarm,” and, on the other hand, “good” immigrants. An incredibly timely book.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Matthew Zapruder, Father’s Day

Copper Canyon, September 3

One of our funniest, most technically virtuous poets enters an intimate, new stage of work in his moving fifth collection. Full on un-celebratory anthems and disquieting odes, this is not just the testament of a man who has entered the permanent stage of life. These poems also read like the record of a poet wrestling with wreckages too big and too circumambient to laugh off.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Hanif Abdurraqib, A Fortune for Your Disaster

Tin House, September 3

Poet, essayist, and critic Hanif Abdurraqib’s new poetry collection A Fortune for Your Disaster invokes a host of pop cultural iconography, including the ghost of Marvin Gaye, Fall Out Boy, and Nikola Tesla as he appears in The Prestige, using them to understand and enact the tripartite magic trick of coming to terms with loss. Abdurraqib asks “how can Black people write about flowers at a time like this?” and shows us how and why he must, capturing all the beauty, vitality, and brevity of flowers and music and the lives of Black people.

–Kevin Chau, Editorial Fellow

Pico Iyer, A Beginner’s Guide to Japan

Knopf, September 5

Pico Iyer isn’t one to rest on his laurels. With the release of Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells earlier this year, his next book from Knopf will be his second this year. Iyer is a longtime writer for TIME and a man whose love for Japan is deeply affecting. A Beginner’s Guide to Japan is just that: Iyer uses conversations he’s had with friends to help him characterize the nation for those who don’t know it well, beyond the superficial “kiss and fly” of what we see on the news, in movies and, well, less deftly-written books.

–Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Caitlin Doughty, Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs

W. W. Norton, September 10

Doughty’s From Here to Eternity took her on a trip around the world to discover how other cultures care for the dead. Now, the mortician and funeral director answers real questions from kids about death, dead bodies, and decomposition. “What would happen to an astronaut’s body if it were pushed out of a space shuttle?” Kid, I want to know too.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Margaret Atwood, The Testaments

Nan A. Talese, September 10

Does this pick even need an explanation? Margaret Atwood’s brilliant dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, has been enchanting readers since 1985. (And Hulu’s adaptation has been engrossing audiences since 2017.) Partially inspired by questions posed to the author these past few decades, partially inspired by the current political climate, The Testaments welcomes us back into Atwood’s Gilead.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Emma Donoghue, Akin

Little, Brown, September 10

As we know from Room, Emma Donoghue is excellent at writing children (no easy feat). In Akin, the child is slightly older, an 11-year-old in need of a guardian, who he finds in a great uncle about to embark on a trip from New York to his birthplace in France. The two make the journey together, in what sounds like the perfect blend of historical mystery, family saga, and odd-couple travelogue.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Jhumpa Lahiri, ed., The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories

Penguin Classics, September 10

What a wonderful thing that 20 years after the publication of her Pulitzer Prize-winning story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, Jhumpa Lahiri crowns her public turn as an Italophile and translator with an edited collection of stories, more than half of them translated into English for the first time, by more than 40 Italian authors, from Elsa Morante to Italo Calvino. It could hardly come at a better time, when Elena Ferrante’s novels and the American revival of Natalia Ginzburg are igniting new interest in the literary traditions of the Belpaese.

–Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Petina Gappah, Out of Darkness, Shining Light

Scribner, September 10

“This story has been told many times before, but always as the story of the Doctor.” In this new novel, from the Zimbabwean author of The Book of Memory, the story will be told as that of the men and women who carried the body of Doctor Livingstone from inner Zambia, where he died of malaria, to the coast, so that it could be returned to England. (As a person who wrote poems about Dr. Livingstone in the third grade, but was told nothing of this side of things, I am avid to read this one.)

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Vigdis Hjorth, tr. Charlotte Barslund, Will and Testament

Verso, September 10

Long described as the Dorothy Parker of Norway, so revered in that country young feminists wear t-shirts there that say, “What Would Vigdis Do?,” Vigdis Hjorth has taken a perplexingly long time to be brought into English. The energy and fury of Will and Testament only increases that feeling. This devastating, short novel tells the story of what happens when the inheritance of a family summerhouse includes a terrible Trojan horse: the trauma which was wrought on children there. Houses have played a significant part of Hjorth’s work, but here it is haunted, an echo-chamber for an unforgivable past.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Howard Jacobson, Live a Little

Hogarth, September 10

Howard Jacobson stole my bitter, angry heart with his blackly comic novel J, and each of his works that I’ve read since has further affirmed that he is one of the great comic geniuses of our time. I can’t wait to read his new tale of septuagenarian romance and chuckle, bleakly, at the absurdity of it all . . .

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Jean-Baptiste Amo, tr. Frank Wynne, Animalia

Grove Press, September 10

Three generations of a pig farm in rural France come vividly to life in this powerful novel about the industrialization of food and the belief systems which bolster a way of life that depends on treating land and its animals like “resources” to plunder. This is not a novel that says just try to recycle a bit more: it is a book that confronts a reader with a stark moral reckoning of the costs of eating meat. There are characters too, but the main character, here, troubled and chased through these pages, is the farm. Fans of Édouard Louis will find a thrilling fellow-traveler here.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Nicholas Lemann, Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

FSG, September 10

Because it is mysterious and has an impact on us all, we often think of the economy as if it’s the weather: a roughly cyclical pattern of naturally occurring events whose extremes are most devastating to those on the margins. Yeah… but no. The economy is made of people, people who make decisions, sometimes bad ones. As we find ourselves in the middle of new and amped up Gilded Age, Nicholas Lehmann, a staff writer at The New Yorker, traces the decline of American institutions in the face of unchecked corporate growth, focusing on individual lives and how they’ve changed—and been changed—by an American economy that seems to pump prosperity ever upward.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Joy Harjo, An American Sunrise

W. W. Norton, September 10

Joy Harjo, who in June became the first Native US poet laureate, told The New York Times recently that her work is “about confronting the kind of society that would diminish Native people, disappear us from the story of this country.” Her new collection continues that work, weaving her life with the history of the Mvskoke Nation and their ancestral land with a stunning new series of poems.

–Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Sarah Pinsker, A Song for a New Day

Berkley, September 10

The beginning of Pinsker’s near-future novel is all too possible: after endless shootings, bomb threats, terrorist attacks, and viral outbreaks, the government forbids large public gatherings. Before this, Lucy Cannon was about to become a rock star—now, with concerts illegal, she begins performing in small, clandestine shows. This is where Rosemary Laws, who, being born in the “after,” lives almost entirely in virtual reality, must find her—in an attempt to turn what’s left of the real into more of the virtual.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Amitav Ghosh, Gun Island

FSG, September 10

The scale of the climate crisis we are facing and the consequences it is producing is so undeniably huge as to seem, at times, surreal. Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island responds to it, and the waves of migration resulting from it, with a narrative that brings the supernatural and folkloric into everyday life as its protagonist Deen Datta—a rare book dealer—travels the world, confronting these consequences in the lives of a various cast of characters.

–Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Jake Skeets, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers

Milkweed, September 10

Jake Skeets’ debut collection Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers examines homosexuality and homosociality among Diné men in Drunktown, New Mexico, a southwestern desert town where desire and violence go hand in hand. The poems’ spare verse and direct language offer no shield from the brutality and beauty of the landscape, like flesh mauled by dogs and stuffed with a mouthful of flowers.

–Kevin Chau, Editorial Fellow

Stephen King, The Institute

Scribner, September 10

As we wait for the follow up film to It to come to theaters, King once again puts enormous powers in the hands of babes—but what will the gifted children starring in his latest do with their special abilities, and what do their strict taskmasters at their mysterious training facility plan to do with their vulnerable, yet dangerous, young charges?

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Diego Osorno, tr. Juana Adcock, Carlos Slim: The Power, Money, and Morality of One of the World’s Richest Men

Verso, September 10

One of the world’s best reporters tells the story—what can be told of it—of Carlos Slim, Mexico’s richest person, and the first from a developing country to make it to the top of the Forbes list. Based on over 100 interviews, and three lengthy ones with his very private subject, Osorno tells a remarkable tell of how the child of Lebanese immigrants slowly put together an empire that stretches from airlines to telecoms and health care. First as a trader, then as investor, then as an owner. The breadth of Slim’s interests are jaw-dropping, from soft drinks and construction to mineral extraction and hotels, tobacco and tile companies. He even allegedly bought the building in which the New York Times is housed. (He’s also the single largest share-holder in the paper). Osorno’s take on this tentacular growth is largely just making it legible, but he comes to a conclusion that aside from Slim’s gift at mathematics, his ability to work within a political power structures is what’s made him a behemoth.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Jesse Ball, The Divers’ Game

Ecco, September 10

A new novel by Jesse Ball is almost always worth reading—in large part because you don’t know what you’re going to get, though in general terms you can expect a sort of highbrow playfulness and oddball experimentation, and I’m always here for that. The Divers’ Game is set in a society marked by extreme social inequality—one class (they began as refugees) is forced to amputate their thumbs and wear a brand on their faces, and can be killed by members of the higher class at any time, without consequence. The novel is a series of short views of life from different perspectives in such a world—a recipe for a chilling satire.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Jacqueline Woodson, Red at the Bone

Riverhead, September 17

The second novel for adults (after 2016’s extraordinary Another Brooklyn) from National Book Award-winning YA writer Woodson, Red at the Bone is the story of two families from different social classes, brought together by a surprise pregnancy and the child that it produces. Woodson always writes with such insight and lyricism about race, class, and sexuality, I cannot wait to read this multi-generational family saga, which Publishers Weekly has already called “a wise, powerful, and compassionate novel.”

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Anne Boyer, The Undying

FSG, September 17

A week after her 41st birthday, poet and Whiting Award winner Anne Boyer was diagnosed with a highly aggressive triple negative breast cancer. In her memoir which explores the “gendered politics of illness” and her treatment’s aftermath, Boyer writes beautifully “meditation on pain, vulnerability, mortality, medicine, art, time, space, exhaustion, economics, care,” exploring topics as diverse as the ecological costs of chemotherapy to the poet John Donne. I’d place her alongside other writers who have so expertly and candidly written about their own ongoing illnesses and deaths: Audre Lorde, Kathy Acker, Susan Sontag, and others. As a teaser, you can read the amazing excerpt which appeared in the New Yorker.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon (restored edition)

Scribner, September 17

How shall I describe the many reasons I love Arthur Koestler? First of all, the man was unkillable—he escaped certain death during the Spanish Civil War and barely escaped being subjected to a Stalinist purge, then became an assisted suicide advocate and, refusing to let anything else get to him, ended up killing himself. But that has little to do with his magnum opus, Darkness at Noon, a book which I was assigned to read in not one, not two, but three separate history seminars in college, which is both a sign of its brilliance and its didactic nature. The premise of Darkness at Noon is simple: an interrogator attempts to convince a stalwart Old Bolshevik to confess to betraying the revolution. While his path to the interrogator’s conclusion is circuitous, the Old Bolshevik eventually finds his sense of guilt in his behavior during the purges, and they arrive at the same bleak, emotional truth. I can’t wait to read the glorious new translation, complete with recovered lost material, to be released by Scribner this fall. If you like your books like your dinner parties (i.e. long conversations about politics), then this one’s for you!

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Jonathan Safran Foer, We Are the Weather

FSG, September 17

In which Jonathan Safran Foer makes the case that animal agriculture is the biggest cause of climate change—for one thing, “sixty percent of all mammals on Earth are animals raised for food”—and that the only way to slow it will be for us all to eat less meat. “We must either let some eating habits go or let the planet go,” he writes. “It is as straightforward and as fraught as that.”

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Attica Locke, Heaven My Home

Mulholland, September 17

Attica Locke’s second book to feature Darren Matthews has the deeply ambivalent ranger tracking down a missing boy, stranded in the midst of Lake Caddo. First introduced in Locke’s Edgar-winner Bluebird, Bluebird, Darren’s on a quest to save the boy—and take down his white supremacist family at the same time. We’re recommending this book because it, like all of Attica Locke’s previous works, is bound to be amazing, but also because the Texan on staff is chuffed to have an opportunity to mention that Lake Caddo is the only natural lake in Texas.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Naomi Klein, On Fire

Simon & Schuster, September 17

For a quarter century, now, Naomi Klein has been an outspoken and fearless voice on that which late-stage hyper-capitalism has wrought upon the world: income inequality, overreaching corporate power, for-profit empire building and, of course, the consequent climate crisis. Honestly, we don’t deserve her, and looking back at her seven books one can’t help but think of Cassandra, her warnings ever accurate yet unheeded… For all that, with her eighth book, On Fire, Klein collects her longform writing on the climate crisis—from the dying Great Barrier Reef to hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico—and somehow manages to strike a hopeful not as she calls for a radical commitment to the Green New Deal, the kind of collective mobilization that saved us from the brink in WWII, and might be our only hope now.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Kevin Barry, Night Boat to Tangier

Doubleday, September 17

I am an OG Kevin Barry fan, down since day one when he published his first collection with the small Irish press (and my old place of employment) The Stinging Fly. Barry’s new book, the story of two Irish criminals biding their time in the Spanish port city of Algeciras, is full of foreboding and of ghosts, not least that of Samuel Beckett, and is continuing proof of this writer’s ability to pack more personality and mordant wit into a single sentence than most writers can manage in a novel.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Brian Allen Carr, Opioid, Indiana

Soho Press, September 17

Brian Allen Carr isn’t messing around. Opioid, Indiana drops you right in with seventeen-year-old Riggle and his dire situation: his parents are dead, his uncle is missing, and he needs rent money fast. His desperation leads him face-to-face with the opioid crisis. Sometimes gut-wrenching, sometimes heartwarming, Opioid, Indiana paints an empathetic portrait of a survivor.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Marc Randolph, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea

Little, Brown, September 17

I can remember my shock when video rental stores were shuttered and the pastime of browsing aisles for movies and video games went out of vogue. Fast forward some years, and here I am with my friends and family streaming content on Smart TVs, or squirreling away in a restroom to watch Mad Men on my phone [Ed. note, Aaron what?]. Netflix has changed more than just our viewing habits. It feels like it has also relocated the family room and shifted the hearth. I’ll admit that memoirs by business executives have never interested me, but I’m making an exception for Marc Randolph, co-founder and former CEO of Netflix. I’m hoping Randolph’s story will give me something more than a basement start-up origin story. I suspect I’ll need something to dab my eyes while reading the chapter on Blockbuster.

–Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Craig Johnson, Land of Wolves

Viking, September 17

No “most anticipated” list for fall 2019 would be complete without including the latest Longmire novel from Craig Johnson, whose beloved Sheriff Walt is back in Wyoming after his most recent and tumultuous investigations in Mexico. No time for him to recuperate, though, as a would-be suicide in shepherd country draws his attentions and a new Basque crime family rears up.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Eric Foner, The Second Founding

W. W. Norton, September 17

It feels especially important, right now, to be reading about both the Constitution and the Civil War. The Second Founding traces the history of the Reconstruction amendments, which abolished slavery, granted all people equal protection under the law (theoretically, anyway), and gave black men the right to vote. Sounds like a necessary read.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Benjamin Moser, Sontag

Ecco, September 17

One of the most important American intellectuals of the 20th century ever also happened to be one of the most interesting Americans ever (if any of that gives you pause, please A) reread her work B) check out her diaries C) why not both!). So it’s fitting that she’s getting a MASSIVE and IMPORTANT biography that manages to capture her life with the same balance of erudition and flare she brought to living it. If you’re reading this, you’re probably already aware of Benjamin Moser’s intellectual sleuthing and if that even remotely piqued your interest, you’ll find the whole book pretty damn compelling.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Water Dancer

One World, September 24

We know by now that everything Ta-Nehisi Coates writes is required reading, whether it’s a case for reparations, a letter to his son about the realities of being black in the United States, a trenchant examination of the of Obama years, or an installment of the Black Panther comic series. September sees the publication of Coates’ debut novel—the harrowing, fantastical story of a young man, born into bondage on a Virginia plantation, who develops a mysterious power that saves his life and sends him on a journey “from the coffin of the deep South to dangerously utopic movements in the North.”

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Alice Hoffman, The World That We Knew

Simon & Schuster, September 24

The latest novel of the beloved and prolific Hoffman (author of Practical Magic, among other things) is a historical novel set in Berlin in 1941 that tells the story of three women, one of them a golem, escaping from the Nazi regime. “Hoffman’s exploration of the world of good and evil, and the constant contest between them, is unflinching; and the humanity she brings to us—it is a glorious experience,” wrote Elizabeth Strout of this novel. “The book builds and builds, as she weaves together, seamlessly, the stories of people in the most desperate of circumstances—and then it delivers with a tremendous punch. It opens up the world, the universe, in a way that it absolutely unique. By the end you may be weeping.”

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Kathleen Jamie, Surfacing

Penguin, September 24

One of the UK’s finest poets, Jamie is also a sensitive and earthy essayist, a Scottish cousin to the Rebecca Solnit of The Field Guide to Getting Lost. These linked essays sound the echoes of a woman in her home landscape, watching and seeing its animal life, tending to the chaos of aging parents and friends. In each one, her consciousness surfaces like a diving bell, rising for air, hands on something still slick and wet from the deep.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Nicolás Giacobone, tr. Megan McDowell, The Crossed-Out Notebook

Scribner, September 24

You know how sometimes you lock yourself in a room and promise yourself you’re going to write something and it never actually happens? Well, The Crossed-Out Notebook is sort of like that, plus kidnapping. A failed novelist is kept in a basement by a world-famous director and forced to write a masterpiece. He spends the day writing, gets threatened with a gun (you know what Chekhov said about that), toils all night, crosses out everything he’s written (relatable), and begins again. This dark comedy/suspense novel is a page-turning take on the conditions in which we can create. Misery sure loves company.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

László Krasznahorkai, tr. Ottilie Mulzet, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming

New Directions, September 24

If you’re a fan of Krasznahorkai, you already know that you need to read this one: the final volume in his four-part series, in which the aging Baron Bela Wenckheim proceeds home to Hungary, to the highly absurd town of his birth.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Maaze Mengiste, The Shadow King

W. W. Norton, September 24

It took Maaza Mengiste the better part of a decade to research and write her second novel, a war epic set during the Italian invasion and occupation of Ethiopia from 1935-41. The Shadow King is largely about the Ethiopian women who joined the anti-European resistance, picking up guns, hauling firewood, or steeling the male warriors who frankly could not have gone on without them. A confession: I have read the novel already and look forward to reading it again. Mengiste’s prose is light and piercing, and she addresses a rarely discussed period in 20th century history that now finally has its place in the sun.

–Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Patti Smith, Year of the Monkey

Knopf, September 24

The warmth and curiosity with which Patti Smith observes her own life makes her one of the finest living companions to living. In M Train and Just Kids, she rendered her own experience ours, then slipped out of the frame like a ghost—leaving behind the mist of memory’s memory. In this elegant new book, though, she shifts into a slightly more present note, chronicling the year of 2016. Drawing on photographs and her experience traveling the country, she manages to make that fateful year both bigger and more mysterious than one would think possible. Traveling from California to Arizona, visiting friends, well and ill, facing loses of her own, this diary of change and destruction is at once a solace and a charge to double down on love.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Lauren Duca, How to Start a Revolution

Simon & Schuster, September 24

There are going to be a lot of genuine exclamation points in this blurb because it is about how young people are changing the world, and I—office baby—enthusiastically agree! Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the youngest woman ever to sit in Congress! David and Lauren Hogg, Parkland survivors, have made themselves the face of gun control advocacy! This list could go on, but maybe you should just read Teen Vogue columnist Lauren Duca’s new book, which celebrates these victories and lays the groundwork for what’s next.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

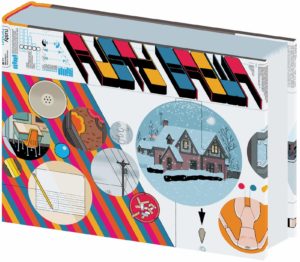

Chris Ware, Rusty Brown

Pantheon, September 24

A new graphic novel from Chris Ware, author of Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth and Building Stories, is always a major literary and artistic event. This one, described by the publisher as “a fully interactive, full-color articulation of the time-space interrelationships of three complete consciousnesses in the first half of a single midwestern American day and the tiny piece of human grit about which they involuntarily orbit,” is 16 years in the making, and I expect it to be spectacular.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Patrick Modiano, Family Record

Yale University Press, September 24

If you’ve read one book by the French Nobel laureate, you’ll recognize the set up here: the familiarity of Paris, the present’s judder when a figment of the past reappears, the sudden vertigo as Modiano or a stand-in peers at the source of shame, wondering why he alone, in his shattered family, seems to care. It’s all here and yet, as ever with Modiano, the tiny alterations to this script mean this is not just more of the same, but a new tack into his dreams of a gone world. Driven by sumptuously perfect vignettes—tales of collaboration nearly forgotten, run-ins with a deposed King, the chronicle of life as a father—this book deepens the sense of unease and candor from which Modiano’s work so endlessly proceeds.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Sara Quin, Tegan Quin, High School

MCD, September 24

Tegan and Sara Quin helped me, and many others, survive adolescence with their particular combination of upbeat angst, effervescent queer pop, and they-just-don’t-understand anthems, so I’m beyond excited that the legendary sisters are publishing a memoir about the earliest days of what would become one of the most popular bands in the US—the lifespan of which covers an entire era of new legal rights and recognition for queer people in this country.

–Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Leslie Jamison, Make It Scream, Make It Burn

Little, Brown, September 24

Leslie Jamison is a writer of supreme eloquence and intelligence who deftly combines journalistic, critical and memoristic approaches to produce essays that linger long in the memory. Her eclectic latest includes examinations of the museum of broken relationships, the community of Second Life players, and the loneliest whale in the world, as well as personal reckonings with marriage, maternity, and becoming a stepmother. The thought of that whale alone is enough to compel me to pick up this collection.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Ann Patchett, The Dutch House

Harper, September 24

I’m always here for another novel from Ann Patchett: she can be reliably counted on for rich, textured worlds and captivating characters. This latest is a big family novel set over five decades, and it revolves around the titular Dutch House—a mansion meant to signify success that leads to endless trouble.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Antonio Lobo Antunes, tr. Jeff King, Until Stones Become Lighter Than Water

Yale University Press, September 24

Lobo Antunes’ experience as a soldier stationed in colonially occupied Angola marked and altered him—perhaps made him the writer he is today. The brutality and mendacity of that time surges back to the fore in this new book, which unfolds in 23 chapters, each just one long sentence. The story revolves around a Portuguese soldier who adopts an Angolan child after the army destroys the boy’s village. Weaving in and out of a symphony of voices, the novel feels more like music than prose, and its horrific climax a past that never accepts being past.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Anne Serre, tr. Mark Hutchinson, The Fool and Other Moral Tales

New Directions, September 24

From The Fool and Other Moral Tales, we’ve been promised a tricky tarot deck, a writer-hero, and a happy polyamorous family in three wild novellas. Tied together with dream logic, each of these stories plumbs the depths of desire, morality, and our willingness to go on an unpredictable ride.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor