Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2019, Part 2

What We're Looking Forward to, July through December

Well, we’ve done it. For better or worse, we’ve made it halfway through 2019. So now that you’ve read all of the books we anticipated in the first half of the year (right?), it’s time for a new list to power us all through until December, a month in which full-on hibernation becomes an acceptable life choice. Until then, you can look forward to books from big names (Colson Whitehead, Téa Obreht, Margaret Atwood, Salman Rushdie, Stephen King, Lydia Davis, Ta-Nehisi Coates), buzzy debuts (Jia Tolentino, Kimberly King Parsons, Ruchika Tomar), and everything in between.

*

JULY

James Tate, The Government Lake

Ecco, July 2

I love James Tate’s poetry, which has a way of distracting you with humor so you don’t notice until too late that it has totally gutted you (read the poem “Distance From Loved Ones” if you don’t know what I mean. Or if you do know what I mean—it’s a perfect poem). Tate died in 2015, and this is his last collection. I expect to read it and proceed to press it on everyone I know.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Svetlana Alexievich, Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II

Random House, July 2

If God existed, or had an ear, she might listen the way Svetlana Alexievich does to the stories of her fellow ex-Soviets. This latest book from the Belarusian Nobel Laureate builds a cathedral from the tales of children. During World War II they were orphaned, uprooted, sold into labor, forced to work, and yet still, amidst it all, remained children. Their stories have a hallucinatory clarity, like visions or nightmares—except they are made simply from the stuff of life. Would that we could live long enough to absorb what their stories tell us.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Marcy Dermansky, Very Nice

Knopf, July 2

Based on the descriptions I’ve read of this novel—a sexy summer read that’s also very funny and which takes place in “the rarefied circles of Manhattan investment banking, the achingly self-serious MFA programs of the Midwest, and the private bedrooms of Connecticut” it may have been written specifically to appeal to me. Or maybe I just like things that a lot of other people also like? Either way, I will be reading Very Nice this summer, hopefully outside.

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Lisa Taddeo, Three Women

Simon & Schuster, July 9

Over eight years, Lisa Taddeo interviewed three women from different parts of the country about desire, sex, marriage. As narrative nonfiction, it’s a page-turner, but as a look at the state of erotic America, and American women, it also feels timely and new.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Tawfiq al-Hakim, tr. William Maynard Hutchins, Return of the Spirit

Penguin Classics, July 9

When Naguib Mahfouz won the Nobel Prize, the great writer’s reaction was: “If Tawfiq al-Hakim were alive, he would have won it.” Although Mahfouz is read still the world over today, al-Hakim has been forgotten. Known primarily for his dramas, he was also a novelist, and it’s exciting to see Return of the Spirit, his 1933 masterpiece, finally ennobled with a Penguin classic spine. This trailblazing Egyptian novel about the days leading up to the 1919 revolution has a vibrancy and immediacy which makes it feel like it was written in 2019, not about events of a century ago. Mahfouz once put his finger on why. “Return of the Spirit I believe marked the true birth of the Arabic novel,” he said in an interview. “It was written using what were then cutting-edge narrative devices. Its predecessors, on the other hand, had turned toward the Western novels of the nineteenth century for inspiration. Return of the Spirit, in that context, was a bombshell.” Using a free-indirect style and cinematic cross-cutting, Return of the Spirit tells the tale of a patriotic young Egyptian and the crisis of faith he undergoes as the state around him implodes. In a terrific introduction, Alaa Al Aswany describes the book’s effect on Egyptian letters and politics, tracing its impact to the 1952 revolution which ended the British occupation of Egypt and led to the start of the Nasser Era. In a year when one of the most exciting publications is of a seventy-year-old 1000-page novel translated from the Russia (Vassily Grossman’s Stalingrad), this is should be equally of note.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Martin Clark, The Substitution Order

Knopf, July 9

Clark, a retired judge-turned-author, has been injecting new life into the legal drama in recent years. Now he’s back with another engaging, subversive story, this time about a Virginia attorney who finds himself disbarred and down-on-his-luck. Clark spins an intricate crime story around his protagonist, one that will draw readers in deeper and deeper, but the atmospherics and surprising relationships are what really drive the story.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

Helen Phillips, The Need

Simon & Schuster, July 9

Helen Phillips is one of our most inventive and exciting contemporary writers; I will read pretty much anything she writes. In this case, it’s a surrealist psychological thriller about a paleobotanist who, when a masked intruder enters her home while she’s alone with her two young children, spirals into a strange existential journey. Horror stories about motherhood are so hot right now.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Kevin Alexander, Burn the Ice

Penguin Press, July 9

If you were an early naughties reader of Chowhound and Serious Eats, can remember Williamsburg when it wasn’t too young for you, and still recall when “vegetarian restaurant” meant “Angelica’s Kitchen,” then you’ll share the same kind of thrill I had reading Kevin Alexander’s exploration of the rise (and fall) of American food culture. Alexander posits that American cuisine has had its heyday, and his mini-biographies of dozens of chefs, mixologists, food-celebrities, and restaurant owners is one of the most informative, insider-y, fun reads I’ve had in a while. Even if you haven’t been to a cool restaurant in ten years because, you know, kids and money and not standing on line for things, it’s the kind of book where even inside-baseball feels accessible.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Ruchika Tomar, A Prayer for Travelers

Riverhead, July 9

This hybrid missing-person-mystery/coming-of-age novel from California writer Tomar—a former McDowell Colony, Center for Fiction, and Stegner fellow—is sure to go down as one of the outstanding debuts of 2019. The story of an unmoored young woman who sets off on a dangerous quest across the California/Nevada desert in search of her missing friend, A Prayer for Travelers is a structurally audacious, suspenseful, and deeply-felt story of female trauma and friendship.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Lila Savage, Say Say Say

Knopf, July 9

I may be an easy sell, but it doesn’t take much more than Ottessa Moshfegh recommending a book (and calling it “subversive”—I mean, what a term, coming from her!) to make me want to read it. This debut is about a woman named Ella who works as a caregiver for a woman with a brain injury, and the way the year she spends with her and her husband challenges everything she thought she knew.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Colson Whitehead, The Nickel Boys

Doubleday, July 16

Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad is, to my mind, one of the finest novels of this still-young century, and wild horses couldn’t keep me from his follow-up. The story of two boys sentenced to serve time in a hellish reform school in Jim Crow Florida, The Nickel Boys promises to be another haunting, insightful, and propulsive work of historical fiction from one of America’s greatest living novelists.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Courtney Maum, Costalegre

Tin House, July 16

Maum’s latest novel is told through the perspective—in vignettes, unsent letters, sketches, and dashed-off thoughts—of a teenage girl toted off to Mexico in the late 1930s to live with her art-collector/socialite mother and her cadre of surrealists . . . so basically my dream. Can’t wait to read this one.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

David Szalay, Turbulence

Scribner, July 16

Hopping from time zone to time zone, Booker finalist Szalay’s latest is a Canterbury Tales for our modern era. If the feel of Chaucer’s great book was raucous, bardic, and earthy, Turbulence is an assembly of missed connections, loneliness and abrupt encounters. Each tale introduces us to one person and says goodbye to another, lending this brisk circuit of the globe—from a gardener in Doha to a woman who has taken a pilot to bed in Sao Paolo—the odd strobe-lit order of reality.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Brandon Shimoda, The Grave on the Wall

City Lights, July 23

In this memoir, Shimoda, an American poet of Japanese descent, tells the story of his family, starting with his grandfather, who was transformed into an “enemy alien” by World War II; and in doing so, tells a universal story of the horrors of war both physical and emotional, and the tensions that linger among people long after the wars are over. “Sometimes a work of art functions as a dream,” wrote Myriam Gurba. “At other times, a work of art functions as a conscience. In the tradition of Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, Brandon Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall is both. It is also the type of fragmented reckoning only America could instigate.”

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Daniel Nieh, Beijing Payback

Ecco, July 23

This self-assured debut is both a rollicking good adventure and a stirring meditation on the complexities of modern identity. When college basketball player Victor Li’s father is found murdered, he teams up with his father’s mysterious business associates to investigate (against the advice of his very practical and awesome sister who I wish was real just so we could be friends), and ends up on the trip of a lifetime.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Laura Lippman, Lady in the Lake

William Morrow, July 23

Lippman’s latest takes us back to Baltimore to explore the world of journalism in the 1960s, and the lives of two women—Maddie Schwartz, a 37-year-old Jewish woman who, after leaving her husband and son, doggedly pursues a career as a reporter; and Cleo Sherwood, a black waitress whose body was recently found in a city fountain, and about whom little is known. As the overconfident and naive Maddie obsessively investigates the murder, she encounters characters at the margins of society, from a bartender to the first black policewoman. Lippman tells a story both personal and political, painting a vivid picture of a city, its newsroom, and the privilege and tragedy that characterized the time.

–Camille LeBlanc, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Dunya Mikhail, In Her Feminine Sign

New Directions, July 30

These new poems by Iraqi poet Dunya Mikhail are delicate, beautiful, day-stopping. Mikhail sings of the longing and undoing of exile, mourns the loss of her language, describes its gendering and the re-engineering on her tongue, a poet’s most important muscle. The long sequence at the heart of this book is strong, but oddly not the work which haunts or moves the most. The poems “Eva Whose Shadow is a Swan”—a fitting portrait of a woman at 90, still chased by where she isn’t, and “Rotation,” a poem of exquisite balance—turn in the mind long after the book is closed.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

Kalisha Buckhanon, Speaking of Summer

Counterpoint, July 30

In this strong, atmospheric debut from Kalisha Bukhanon, protagonist Autumn is searching for her missing sister, Summer, while living in a guilt-ridden relationship with her sister’s ex-boyfriend and contemplating the many missing and murdered women of Harlem. This is social justice noir meets psycho-noir, with an end twist you’ll never see coming.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Richard Russo, Chances Are…

(Knopf, July 30)

Richard Russo is often compared to Dickens, to whom he clearly owes a debt, but the ghost hovering over his fabulous new novel, Chances Are . . . feels more like Sam Shepard. Three Vietnam War era classmates get together on Martha’s Vineyard for a high school reunion at age 66 to relive the past. At first this feels like familiar territory. Indeed, Tim O’Brien wrote that novel (July, July). But here the expected layers peel away, and mingling among the regrets of that time, the war, the feelings that maybe they’ve all traveled too far from their working class roots, lies a cold case, and some questions about love that cut to the heart of how these men have spent their hours on earth. Next to Colson Whitehead’s new book, there’s not a better-paced summer read in 2019.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor

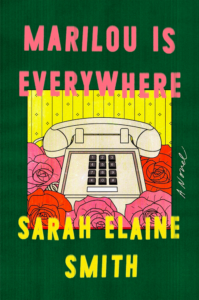

Sarah Elaine Smith, Marilou is Everywhere

Riverhead, July 30

Haven’t we all, at some point, sort of wanted to slip into someone else’s skin? The story starts with an overlooked 14-year-old girl, more or less abandoned by her mother and left to her own devices. Her deep desire to lead a different life causes her to take advantage of the disappearance of another girl, becoming a replacement of sorts. This eerie exploration of desperation and the complexities of maternal love is sure to be a page-turner.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor