Lit Hub Staff Picks: Our Favorite Stories This Month

The Best Writing at the Site in September

From essays to interviews, excerpts and reading lists, we publish around 150 features a month. And though we’re proud of each week’s offerings, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of our favorite pieces of writing from the month at Lit Hub.

![]()

“How the Great Lorraine Hansberry Tried to Make Sense of It All“ by Imani Perry

Imani Perry’s essay, excerpted from her new biography Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, is a clarion call for reengagement and remembrance. Perry encourages us to look beyond the flattened legend of Hansberry’s most famous work and premature death, to achieve a fuller understanding of who she was as a artist, an activist, and a person. As Perry writes in this piece: “She did things that were politically dangerous. She was brave and also fearful; experimental and superb. She failed and hurt. Her tradition, then, cannot be reduced to the picture of greatness. It has to entail the vagaries of imagination and the many circumstances that excite it.”

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

“Don’t Write A Book About Cancer, And Other Advice” by Shirley Barrett

“Don’t Write A Book About Cancer, And Other Advice” by Shirley Barrett

Along with the noted writerly advice to write what you know, Barrett recommends not writing a character with cancer because after she wrote The Bus on Thursday where the main character has cancer, she got it too. Barrett is acerbic and funny. Do I want to laugh at a woman dealing with a horrible disease? No, but when she describes not wanting to wear an expensive wig because, being in humid Sydney, it “felt like having a small wombat perched atop my head” you kind of have to.

–Emily Firetog, Managing Editor

“The Debut Novelist’s Guide to Battling Imposter Syndrome” by Sharlene Teo

“The Debut Novelist’s Guide to Battling Imposter Syndrome” by Sharlene Teo

No matter how much time we spend with imposter syndrome on our own—staring at blank screens, crumpling up half-used notebook pages, scouring ZipRecruiter for alternate professions—I don’t think we give it a lot of air time when we talk about writing. In Sharlene Teo’s essay, the imposter rears its ugly head. I don’t think I’ve ever read anything that pinpoints this feeling so specifically. Imposter syndrome follows you everywhere. It’s, as she says, “cleaved to the breastbone.” The imposter takes on a life of its own. It becomes a she. She comes to parties and does “a drunken victory dance.” But she doesn’t just show up and then disappear after Teo’s first novel, Ponti, gets published. This is important. This essay is so wonderfully honest and is definitely recommended reading for every writer who feels “like a hard-boiled egg that has been shelled and left out on the counter.”

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

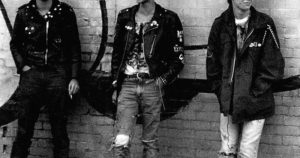

“A Life of Crime Fiction and Gangster Rap” by Tod Goldberg

“A Life of Crime Fiction and Gangster Rap” by Tod Goldberg

In this essay, Goldberg draws the connection between the crime novels he grew up with—greats like Elmore Leonard and Lawrence Block—and the gangsta rap coming out of the West Coast in the late 80s and early 90s, in particular NWA and Ice Cube’s iconic opening line: “Straight outta Compton, crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube.” “This wasn’t a third-person story anymore,” Goldberg writes, “nor was there any equivocation, instead, this was a first person narrator telling you that he was a crazy motherfucker, which tells the listener, in seconds, that anything can happen.” Goldberg frames rap as an evolutionary crime fiction and grapples with his own audio history, from the thrill of bumping NWA during a summer job on a golf course to his adult reckoning with hip hop’s misogynistic threads. This is one of those essays that takes you in a dozen directions you didn’t see coming, each one an insight into an art form and an individual.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Editor

“Why Literature Loves Lists” by Brian Dillon

“Why Literature Loves Lists” by Brian Dillon

As Literary Hub’s resident listmaker, I think I’m contractually obligated to choose this one, if only because it soothes my existential angst and justifies my place in the world. (But also: it’s good.) In this essay, Dillon examines the use of the “list, catalogue, enumeration, inventory, schedule, register, tripos, tally, syllabus, almanac, table, atlas, index, calendar, rota, ledger, scroll, manifest, invoice, prospectus, program, menu, census, directory, gazetteer, dictionary, lexicon, gradus” in the work of William Gass, Rabelais, Joan Didion, James Joyce, Georges Perec, Lynne Tillman, Oscar Wilde, and oh look, this has become another list. Seems inevitable, really.

–Emily Temple, Senior Editor

“How I Went From Writing Ads About a Stone Puppet to Writing a Memoir” by Leah Dieterich

“How I Went From Writing Ads About a Stone Puppet to Writing a Memoir” by Leah Dieterich

I have claimed in more than one cover letter that writing poetry is great preparation for other, more lucrative kinds of writing (copy, speech, shopping listicle), so I loved reading an essay about a different direction of influence—bringing the lessons of advertising to the realm of literary memoir. Dieterich also speaks to the familiar (to me, at least) fear of wasting your time on the wrong kind of writing, as if you’re somehow dulling your rapier wit by grinding it against the stone of capitalism (please note that I do not blame my employer for that horrible metaphor).

–Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

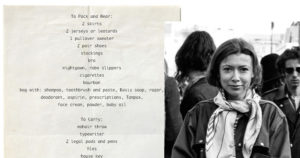

“How the First Punk in East Berlin Became an Enemy of the State” by Tim Mohr

“How the First Punk in East Berlin Became an Enemy of the State” by Tim Mohr

I’m a sucker for people’s subculture origin stories, so of course I’d pick this account of how a 15-year-old girl became the first punk in East Berlin. This excerpt from Tim Mohr’s Burning Down The Haus is a cut above the usual thanks to the sociopolitical context in which Britta Bergmann, said teenager, transformed into Major (a nickname acquired after she started wearing epaulets and other punk paraphernalia), and the alarm she caused. With its exploration of Major’s political upbringing and desires, the piece struck me as an apt homage to the power and interiority of the “weird” teenage girl, a figure relegated too often to cartoonish stereotype.

–Miriam Kumaradoss, Editorial Fellow

“How George V. Higgins Invented the Boston Crime Novel” by Scott Von Doviak

“How George V. Higgins Invented the Boston Crime Novel” by Scott Von Doviak

I once went to a fiction workshop where the author leading the workshop used the first chapter of The Friends of Eddie Coyle as his example of the best crime opener of all time. I think everybody who’s read the book will understand why I still wince at the memory, but the outsized impact of this novel is more about the many works influenced by it than the many readers scarred by the terrible things that happen to hands in this scene. Here, Scott Von Doviak examines how this dialogue-heavy hard-boiled tale of petty criminals and their woes helped set the tone for many a Boston crime novel to come.

–Molly Odintz, Associate CrimeReads Editor

“My Best Friends Are Books” by Sara Gran

“My Best Friends Are Books” by Sara Gran

Sara Gran, known in the crime fiction community as a writer’s writer, here rounds up six of the books that have made the most impact on her own writing. I love how eclectic this list is, and especially the shout-out to The Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, one of my all-time favorites, and up until now, probably never before included on a list that also prominently features Rex Stout and Maggie Estep. Gran writes that “Here are some of my best friends, and the crime writing lessons I learned from them; I hope these introductions will make new friendships, and I hope these friendships will serve you as well as they’ve served me.” Her love of books as more than impersonal objects gets to the heart of our emotional attachment to our libraries, and I think most readers can relate to her object-love, and the emotional fulfillment we can get from stories.

–Molly Odintz, Associate CrimeReads Editor

“Power Walking” by Aminatta Forna

“Power Walking” by Aminatta Forna

Aminatta Forna’s essay about the perils of moving through and occupying public space is so bold and fresh and furious, it makes me wish everyone who ever read Garnette Cadogan’s 2016 “Black and Blue” reads this too. The tales assembled here remind that for every flaneur of Cadogan’s stripe, who dresses and moves to anticipate the gaze of the police, there’s a woman like Forna who is making a similar set of adjustments, as she’ll be dealing with the unwanted attention of non-uniformed men, too. Forna’s stories about the way she does this, when she talks back, and how race, gender and location change the manner in which she is spoken to is just dazzling. We have our Didion of the 21st century, by the way, she just doesn’t drive a Stingray–and her name’s Aminatta Forna.

–John Freeman, Executive Editor