A crack echoed through the boreal landscape, a momentary chaos in the still afternoon air. In the near distance, a large bull moose fell to its side. Evan Whitesky stood and looped his rifle around his right shoulder, adjusted his neon orange hat, and began a slow walk over to his kill. The smell of gunpowder briefly dominated the crisp scent of impending winter.

His grey boots pushed through the yellowing grass of the glade. Evan was pleased. He had been out since early morning and had been tracking this particular bull since around noon. The fall hunt was drawing to a close, and he still wanted to put more food away. Food from the South was expensive and never as good, or as satisfying, as the meat he could bring in himself.

By the time Evan reached the moose moments later, it was dead. Massive antlers propped up its head. The eyes were open, vacant, and the bull’s long tongue flopped out onto the grass. Evan reached into the right pocket of his cargo pants and pulled out a small leather pouch faded and smooth from years of wear. He brought it up to just below his chest and balanced it in the centre of his palm. He ran his thumb across the small beaded pattern in the middle, feeling where the beads were missing in the simple bear design. I’ll ask Auntie to re-bead this later this fall, he thought.

Evan looked down at the beautiful design: a black bear in a red circle edged in white. At least half the outer white beads were gone and there was a bald patch near the bear’s head and hind legs. Most of the beaded bear itself remained, though. He untied the leather string and pinched some tobacco into his open palm. It came from a plastic pouch of rolling tobacco he bought at the trading post on the way out—he’d forgotten to get the dry, untreated tobacco, or semaa, from his medicine bundle before leaving the house. The shredded, manufactured leaves seemed to gum together. He bounced the tiny heap in his left hand before wrapping his fingers around it. He closed his eyes.

“Gchi-manidoo,” he said aloud. “Great spirit, today I say miigwech for the life you have given us.” He inhaled deeply and paused. This was still a little new to him. “Miigwech for my family. And for my community. Miigwech for our health. Chi-miigwech for the life you have allowed me to take today, this moozoo, to feed my family.” He still felt a little awkward, saying this prayer of thanks mostly in English, with only a few Ojibwe words peppered here and there. But it still made him feel good to believe that he was giving back in some way.

Evan expressed thanks for the good life he was trying to lead. He apologized for not being able to pray fluently in his native language and asked for a bountiful fall hunting season for everyone. He promised to keep trying to live in a good way, despite the pull of negative influences around him. He finished his prayer with a resounding, solitary miigwech before putting the tobacco on the ground in front of the moose. This was his offering of gratitude to the Creator and Mother Earth for allowing him to take this life. As he took from the earth, he gave back. It was the Anishinaabe way, as he understood it.

His head was clear. The adrenaline surge of the kill was brief, as was his remorse for taking a life. Evan had spent nearly his whole life hunting. His father had first taught him to identify and follow moose tracks in the deep bush around their reserve when he was five. Now, nearly twenty years later, he was on his own, tracking his own kill to support his young family. When he was new to the hunt, the sympathy and sadness he felt after pulling the trigger lasted days. Now he was a father himself and necessity overcame reluctance and regret.

“He still felt a little awkward, saying this prayer of thanks mostly in English, with only a few Ojibwe words peppered here and there. But it still made him feel good to believe that he was giving back in some way.”This is a big fella, he thought. He looked over the bull once more before turning back to where he’d parked his four-wheeler deeper in the bush that morning. He would have to butcher the animal here; it was too big for him to heft onto his ATV’s trailer by himself. On some hunts, he would leave his kill on the land overnight and return the next day with help. But he didn’t have any tarps or blankets with him to cover up the moose and mask its scent from other predators. And the chill in the air told him that he should move quickly.

A deep orange glow coated the northern landscape as the sun began to set, highlighting the deep evergreen of the pine and spruce trees that towered beyond the ridge. As he walked, the sky above became darker blue, and the air was markedly cooler. Overhead, a small formation of geese broke the silence, complaining about their migration south for the season. I thought they were all gone. Had he expected this delayed flock, he would have had his shotgun with him to add to the day’s bounty. But he already had a good stock of plucked and halved geese in a freezer at home; it didn’t matter that much.

He stepped up to the four-wheeler and straddled it, then turned the key in the ignition. The harsh rumbling of the machine racketed across the field, chasing the soothing off-beat cries of the geese. He hadn’t expected to find a moose this close to where he’d first stopped just after dawn. He’d covered vast amounts of open terrain and thick bush throughout the day and he was about to pack it in. But he found a decent spot overlooking the small meadow on the walk back to his vehicle and decided to stop and wait. It had paid off.

The four-wheeler flattened the tall grass as Evan made his way back to the moose. He made a quick inventory of the meat they’d have for the winter: three moose, ten geese, more than thirty fish (trout, pickerel, pike), and four rabbits, for now—more rabbits would be snared through the winter. It was more than enough for his own family of four, but he planned to give a lot of the meat away. It was the community way. He would share with his parents, his siblings and their families, and his in-laws, and would save some for others who might run out before winter’s end and not be able to afford the expensive ground beef and chicken thighs that were trucked or flown in from the South.

The thought of eating only packaged meat if all that game ran out made Evan shudder. “Bad moose meat is always better than a good pork chop,” his father always said. Evan ate southern meats when he had to, but he felt detached from that food. He’d learned to hunt when he was a boy out of tradition, but also necessity. It was harder than buying store-bought meat but it was more economical and rewarding. Most importantly, hunting, fishing, and living on the land was Anishinaabe custom, and Evan was trying to live in harmony with the traditional ways.

The four-wheeler rolled up to the dead moose. Evan turned it off and reached for the green canvas bag strapped to the rack on the back. He pulled out four large game bags for the smaller cuts of meat and the innards, then tossed the bags on the ground next to the animal and brought out his foldable razor knife. It would be dark soon so he had to cut quickly.

The bull’s spoor was strong in his nose as he moved in to bring a hind leg to rest against his torso. He began to cut swiftly and methodically on the inside of the hip, and the skin opened easily, exposing the white tendons and purple muscle beneath. Cutting through further, he pressed against the leg with his opposite shoulder, dislocating the hip joint.

“Bad moose meat is always better than a good pork chop,” his father always said. Evan ate southern meats when he had to, but he felt detached from that food. He’d learned to hunt when he was a boy out of tradition, but also necessity. It was harder than buying store-bought meat but it was more economical and rewarding.Once he had severed the hindquarter, Evan lugged it over to the trailer. He felt the burn in his arms and shoulders as he heaved the meat over the edge and onto the plywood base. He did this for each limb, arranging them neatly on the wide trailer bed, then he cut the meat from the back and neck, gutted what was left, and filled his game bags.

He would have liked to have kept the hide intact. If his dad and a couple of his cousins or buddies were with him, they could have loaded the whole moose onto a truck and done all the skinning and cleaning at home. There they could clean and eventually tan the hide to use for drums, moccasins, gloves, and clothing.

By the time Evan was finished, the sun had crept below the horizon and it was nearly dark. It wasn’t a long trip home and he knew this bush intimately, but he didn’t want Nicole to worry, so he steered his vehicle back to the trail that led to his community.

*

Evan rolled up to the simple rectangular box of his home. The lights were on in the living room but the rest of the house was dark. The kids must be in bed, he thought. He pulled up his jacket sleeve to check his watch. It was well past Maiingan’s and Nangohns’s bedtime. He would see them in the morning.

He backed up to the shed that contained a freezer, a refrigerator, a large wooden table, hanging hooks, and everything else he’d need to finish preparing the moose. It would get cold overnight but not so much that the meat would freeze. He loaded everything inside, shut the heavy door and locked it, and headed into the house.

Evan walked through the front door to an unusual silence. The flat-screen television on the living room wall was off. By now Nicole would usually be watching a sitcom or a crime show. “Aaniin?” Evan announced himself, accentuating the uptick at the end of the word as if to question what was going on.

“Oh, hey,” his partner said from around the corner. “You’re back.”

“It’s so quiet in here,” Evan replied, taking off his heavy outer layer.

“Yeah, the satellite went out earlier,” Nicole said as she stepped into the living room. “I dunno what’s going on. Wind musta blew it offline or something.”

“That’s weird. I thought you’d be laid out on the couch this time of night, as usual,” he teased, with a playful smirk.

“As if. So how was it out there?”

“Got another moose.”

“Right on!”

“Yeah, it took all day. Didn’t see nothing out there all morning. I was gonna give up, then I seen him on my way back to the four-wheeler. Had to quarter him out there. Took longer than I thought.”

“We can give some of that to your parents, eh?”

“Yeah, that’s what I was thinking.”

He untied his boots and stepped out of them before moving into the living room in his sock feet.

“Phone died. Woulda called you to say when I’d be home.”

“I figured as much,” she said.

Evan reached for the charger cable that lay on the side table by the couch and plugged in his phone. He pulled off his black hoodie and threw it over one of the wooden chairs of the modest table set. In the still indoor air, he noticed his hunger.

“Hey, where’s my sugar?” Nicole teased, beckoning for a kiss. “Oh!” He stepped closer to her, his lips in an exaggerated pucker. He placed his hands softly on her hips and gave her a simple kiss.

“You hungry?” she asked.

“Yeah, I just noticed,” he replied. He had finished his last sandwich just before spotting the moose. “That chi-moozoo distracted me, I guess.”

“Well, I put a plate in the fridge for you. You just gotta throw it in the microwave. You’re lucky the kids saved you some.”

She nudged him toward the fridge, and he took out the plate, peeling back the tinfoil covering to reveal a sparsely seasoned chicken leg, mashed potatoes, and frozen peas. His stomach growled as he waited for the meal to heat up.

Evan Whitesky and Nicole McCloud had been in each other’s lives since childhood. He could trace the path of his own life by his signpost memories of her, and she could do the same. He remembered the first time he saw her, swimming at the lake the summer before kindergarten began. She wore a light blue bathing suit and her wet hair was tied into a long ponytail. Her older sister Danielle was watching her. Nicole was smiling and laughing.

They crossed paths again on their first day of kindergarten. She still teased him about the awkward outfit he wore that day: baggy overalls and a red T-shirt with fading yellow cartoon characters on the front and a bowl hair cut that made his head look big. He was shy and didn’t talk much most of the morning, and shortly before the school day broke at noon, he cried for his mother. He went home with wet cheeks and a runny nose.

Being somewhat unacquainted at such a young age was unusual in a community as small as theirs. Their parents knew one another but weren’t close friends or relatives—his mom and her dad both came from different reserves in the South. Basically, they weren’t cousins, and that perhaps destined them to bond as curious friends in elementary school and become a couple by high school. Innocent attraction became intense passion and, despite a year apart when Nicole went to college in the South, it eventually evolved into the loving partnership that bore two beautiful young children. The eldest, Maiingan, was five and had school in the morning. Three-year-old Nangohns was still at home with Nicole.

The kids were what pushed Evan through the bush on the hunt. Feeding them always motivated him to see the task through. He still hadn’t used up all his allotted hunting days from his maintenance job at the community’s public works department, so he decided he’d use the morning to finish dressing the moose. The microwave beeps interrupted his thoughts and he pulled open the door to grab his plate, sitting down across from Nicole, who’d come to the table to join him.

“Well, if the TV’s out, looks like you’re gonna have to entertain me,” he said.

“We might actually have to have a conversation!” she retorted. Her black hair that he loved unbound was pulled back into a tight, practical ponytail and her brown eyes squinted with her laughter. He chuckled and began to eat, careful not to get any mashed potatoes in his patchy black goatee.

“I don’t even remember the last time it was quiet like this in here,” she said. He nodded. “We should keep the TV and that computer off more often,” she continued. “Get the kids outside while we can.”

In the coming weeks, the temperature would drop and the snow would come. Soon after, the lake would freeze over and the snow and ice would be with them for six months. Like people in many other northern reserves, they would be isolated by the long, unforgiving season, confined to a small radius around the village that extended only as far as a snowmobile’s half tank of gas.

Evan finished eating, and his eyes drooped under the weight of his fatigue. He raised his thick black eyebrows to force his eyes open. “That moozoo took a lot outta me.”

Nicole reached under the narrow table and patted his thigh. “You’re a good man,” she said. “You should go to bed. It’s another big day tomorrow. My nookomis keeps saying this winter is gonna be a rough one.”

__________________________________

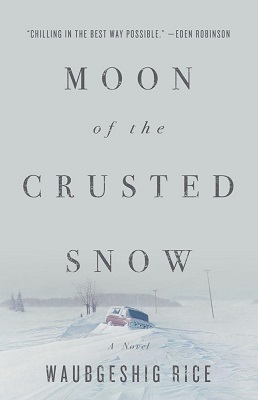

From Moon of the Crusted Snow. Used with permission of ECW Press. Copyright © 2018 by Waubgeshig Rice.