Lisa Hanawalt: Drawing Progressive Westerns from the Horse's Perspective

The Visual Mind Behind BoJack Horseman is Having a Busy Year

Between launching a new Netflix show and art directing the critically acclaimed dramedy BoJack Horseman, LA-based illustrator Lisa Hanawalt wrote and illustrated a new book: out last month, Coyote Doggirl takes aim at the lack of women (and horses) in Westerns.

![]()

In the middle of Coyote Doggirl, a book named for its brash heroine, Coyote finds herself among a tribe of wolves as she heals from an arrow wound. One night, playing with the pups in the purple desert dusk, she gets a naughty grin and scrawls a charcoal horse on a boulder—complete with an enormous penis.

It’s a funny moment, sure. But in it, you catch a glimpse of the book’s author. Lisa Hanawalt, a Los Angeles-based illustrator better known for art directing Netflix’s critically acclaimed BoJack Horseman, has spent the better part of her career using art to subvert, to question, and to make people laugh.

Hanawalt’s new book, sparked by a Sergio Leone binge back in 2013, riffs on classic Western movies. Like all of Hanawalt’s creations, Coyote Doggirl mines the illustrator’s personal obsessions. Horses, anthropomorphic dogs, and technicolor washes of purple and orange render desert mesas and rushing rivers in vivid detail.

“I love Westerns so much, but they’re often really racist and misogynist, and most of them don’t even really acknowledge the horses,” Hanawalt, whose adoration of horses fills her comics, told an audience in 2015. “We don’t even learn their names half the time. That pisses me off. So I made a Western where horses were the focus.”

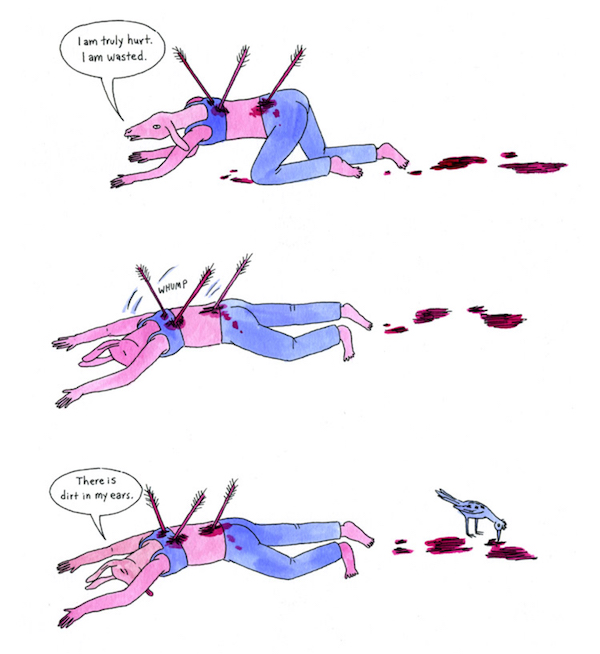

The story follows a loud-mouthed, hot pink dog named Coyote as she flees a trio of dogs who want her dead. When a shower of arrows separates her from her beloved horse, Red, Coyote has to befriend a tribe of wolves, cross rivers and deserts in search of her best friend, and ultimately confront a past she can’t outrun.

As the story evolved, Hanawalt drew early drafts with a male main character, but eventually realized it hadn’t been an intentional choice.

“The character’s basically a version of myself,” Hanawalt said when we spoke over the phone this summer. “So I put a sports bra on her and changed her to a woman.”

Hanawalt wrote 15 pages, and then she wrote more, gradually adding pages as she worked on television projects that demanded nearly all of her attention. At times, an entire year would slip by before she returned to Coyote and Red.

Still, each time she picked the comic up, Hanawalt found that the messy draft was better than she remembered. In 2017, she debated whether to buckle down and finish the story or throw the whole thing away. Her boyfriend, comedian Adam Conover, convinced her not to trash it.

“He was like, ‘That’s ridiculous. You need to keep doing this,’” said Hanawalt. “My worst fear is that I’ve wasted time on something that’ll never actually come to fruition.”

Finally, last summer Hanawalt found space to pick the pages up again. BoJack Horseman was on hiatus, and her new Netflix show, Tuca & Bertie, was still just a fledgling. Hanawalt penciled 80 more pages, and the book was complete as soon as the paint dried. Hanawalt’s agent persuaded her to bring the manuscript to Drawn & Quarterly, a Montreal-based publisher that released her two previous books, My Dumb Dirty Eyes and Hot Dog Taste Test.

Reviews of Hanawalt’s work typically focus on the surreal qualities of her comics, where birds might stream out of a horse’s mouth on an airplane piloted by a pile of worms. Hanawalt’s parents are both microbiologists, and, like them, she seems able to sense the teeming multitudes beneath the surface of things.

For all her art’s inscrutable, dreamlike qualities, Hanawalt admits that she thinks, sometimes obsessively, about how her work will be interpreted before releasing it into the world.

Coyote Doggirl skews less surreal and more skewering. Unlike Hanawalt’s previous books, which curate a selection of her comics and illustrated reviews, Coyote Doggirl offers a single, continuous narrative. Unlike an onscreen Western, Hanawalt’s illustrated characters can ride horses and dive into rivers with acrobatic abandon—but, like BoJack Horseman, they are drawn to a consistent scale, without the impossible mutations that might occur in Hanawalt’s other work. In this sense, Coyote Doggirl feels downright realistic.

“Hanawalt’s work typically focus on the surreal qualities of her comics, where birds might stream out of a horse’s mouth on an airplane piloted by a pile of worms.”

The stakes also feel higher. Putting a female character at the center of a Western felt comfortable to Hanawalt, a vocal feminist, but subverting the genre’s problematic portrayal of Native Americans, less so.

“I wanted to subvert the tropes about Native Americans in Westerns,” Hanawalt said. “Then I started to worry that I was just adding to the negative stereotypes that are already out there, which would be my worst fear.”

Hanawalt’s Native American tribe are coded as a pack of wolves who rescue Coyote after she’s struck down by a volley of arrows. The tribe’s tan teepees dot the yellow and pink desert, where they collect quartz crystals and stitch intricately beaded crop tops while horses graze all around.

In a story told through illustrations, each word carries heavy weight. On one page, Coyote recaps wolves she’s met recently, including River, a blue wolf whose German Shepherd-like ears are adorned with feathers. “Soooo smart,” Coyote notes. “And kind. Kinda aloof but I think they like me?”

I initially read River and Coyote’s scenes with the same anticipatory butterflies I feel while hoping my favorite Terrace House contestants will start dating. On the second read, I sensed something else—a compatibility and friendship durable enough to make romance seem unimportant.

I felt as if I could hear Hanawalt smile through the phone when I asked if the choice to use a nongendered pronoun was intentional. While writing, Hanawalt restlessly switched River’s gender each time she wrote a new draft. Eventually, she realized that the character was nonbinary.

More than any other character, River pushes Coyote to grow. Unperturbed by Coyote’s rude banter, they take Coyote on an overnight hunting trip where, huddled by the campfire, Coyote reveals the painful secret that cost her her horse and earned her an arrow through the chest: She killed a man who attempted to sexually assault her. Romance is ultimately irrelevant to the scenes’ intimacy.

“Making a new friend feels like starting a romantic relationship in so many ways,” Hanawalt said. “It really does feel like a courtship.”

Still, Hanawalt felt uneasy about writing Native American characters. So she brought the manuscript to a sensitivity reader who is also a member of the Navajo tribe. Sensitivity reading is a relatively new trend in publishing, in which an author hires a member of a marginalized group to screen a story for harmful or inaccurate representation.

“I feel like a bull in a china shop sometimes,” said Hanawalt, recognizing the risk of harm and destruction that lurks just beyond the edges of her best intentions. “I’m trying to [create] in the most sensitive way possible, but it’s not entirely avoidable at all times.”

To Hanawalt’s relief, her sensitivity reader found the book to be unambiguously satirical and pointed out several areas—a ceremonial mask, for example—that Hanawalt should tweak. “It was less painful than I thought it would be,” Hanawalt said.

Since she began writing the book in 2013, however, other things have become more painful. During a 2014 Reddit AMA with BoJack co-creator Raphael Bob-Waskerman, a commenter complained that the show spent too much time shoving politics down viewers’ throats.

Hanawalt remembers firing back a joke: “I wish they would slide it down their own throats, but I’m happy to help by shoving!”

The comment sparked social media backlash from Men’s Rights Activists.

“The show was created by feminists,” Hanawalt said while recounting the incident on her podcast, Baby Geniuses. “Fuck you!”

Since Trump’s election and the rise of a national conversation about the prevalence of workplace sexual harassment, Hanawalt has seen the dialogue deteriorate even more.

“Our country is more divided than before. Everything is seen as being for or against the correct team,” Hanawalt said, “which really saddens me because we have more in common with each other than not. People generally want the same things—they want to live a nice life with people they love.”

In Coyote Doggirl, Hanawalt spins a revenge fantasy, but it’s more Ocean’s 8 than Kill Bill. Instead reveling in endless showers of bullets and blood, the story suggests that violence only begets more violence.

“Up until like I penciled it, I intended for her to kill all the bad guys,” said Hanawalt, who’d envisioned a shootout like the ones that movies such as My Darling Clementine always seem to culminate in. “Then I thought maybe that wasn’t the most interesting thing to do.”

The book’s final twist prioritizes Coyote’s ability to take risks and tell her own story. Despite the book’s feminist backbone, Hanawalt chose not to include the word “feminist” in the book’s packaging. “I don’t just want other women to read it,” she said. “I want men to read it, to be changed by it and reconsider things.”

On the morning we spoke, Hanawalt was looking at a busy schedule of Coyote Doggirl promotion, followed by Tuca & Bertie meetings all afternoon.

Nonetheless, things finally seem to be settling down for her, at least by comparison. Earlier in the year, she’d been finishing the book while simultaneously art directing BoJack Horseman and starting Tuca & Bertie’s writers room. She and co-host Emily Heller decided to stop booking guests on their podcast, Baby Geniuses, to save time. The intensity felt like a constant sprint between fires that needed to be put out.

“Not to compare what I do to firefighting, which is way more important,” Hanawalt said, voice abruptly serious. “It was kind of fun, because I didn’t have time to have a panic attack. At one point, I started to cry and I had one tear come out. And then I just sucked it back in because I was like, ‘Nope! No time!’ It was good to know that I can actually handle it.”

But for now, or at least on the day we spoke, Hanawalt finally has enough breathing room to enjoy the ride. “The whole process is much more joyful than I expected,” she said.

Michelle Delgado

Michelle Delgado is a journalist in Washington, DC. Her culture reporting has been featured in The Atlantic, CityLab, VICE, and others.