Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (The Waiting) and Alexander Chee (How to Write An Autobiographical Novel) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a fall event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The driving force behind November’s conversation was Gendry-Kim’s second English-language release, The Waiting, of which Chee has written:

How can black and white drawings do this, you might ask. But maybe only black and white drawings can do this—Gendry-Kim offers us here a glimpse of the heart of a woman who has lost more than some might ever find, and who has never given up her love, if not her hope. The Waiting is a stunning achievement, and a testament to the power of her artistry. Not a line or word feels out of place.

This interview shares the highlights of their conversation, with interpretation offered by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.

*

Alexander Chee: I recently learned that my family is from the same town as yours, Goheung. I was even more excited than I was already after reading your work.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes, you were telling me that your father’s family is also from my hometown.

Alexander Chee: I was really taken with how The Waiting tells the stories of a family of Korean War survivors, whose daughter discovers that her parents are North Korean refugees who married each other, partly with the hope of separating as soon as the country was reunified and they could be with their separate spouses again. This is something that she’s never known.

Just past the novel’s end, you have an author’s note describing your mother’s own hope of reunion, and you’ve talked throughout about how the book is not your life per se and not hers because you hoped through fiction to protect the people whose lives you were describing, which I think is really beautiful. But it also describes an extraordinary resilience. And I wondered if you felt in writing this, this hope, is that the same as this resilience? Is there any difference between them?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: I remember I interviewed an old lady in a very similar situation. She had come down from the north. And I was surprised by her story. You cannot move on to the next chapter of your life. So that was something that I wanted to highlight, the kind of trauma that these people live with.

Could you perhaps repeat the question about resilience for me?

Alexander Chee: I suppose it’s a very subtle point in the end, but I was really struck by the relationship between hope and the will to survive. Nurturing the hope of a reunion in the mother seems almost cruel and yet it seems even more cruel to leave her without it.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes, that’s right. Most members of separated families, including my mother, had to get on with life. They had to make a living. They had to be resilient. They had to look after their children or take responsibility for their family. But at the same time, they had this very faint hope of one day being reunited with their separated family members.

It is something that they have deep inside, but don’t dare to take out and explore. But as they get older, in one corner of their mind, they cannot forget about the family members they have been separated from. So they go back to it every now and then on their own and express it whenever the opportunity arises.

Many of the separated family members are very old, and there are very few of them left. So many of them hope to meet their family members before they die, hoping that their separated family members are still alive. So they hold on to this hope of one day being reunited, and it keeps them going. I’m not sure if I’ve answered your question.

Alexander Chee: I think so. I’m sure many readers, like me, have been greatly moved by your signature style, which is black and white drawings. Is there a reason you work this way in just pen and ink without any color?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: There are actually many reasons. I actually love using colors. I’m not so sure what the weather is like in your country right now, but Korea is having a beautiful autumn. If I had to draw this scenery, I wonder whether I would use color or not. I think I’d want it to be black and white.

I think black and white is somewhat suitable because it conveys a certain atmosphere. It expresses sorrow and the depth of a person very well.If I draw in black and white, then I care more about the strokes. And in terms of drawing techniques, I think black and white is somewhat suitable because it conveys a certain atmosphere. It expresses sorrow and the depth of a person very well. I’ve been drawing that way a long time and I really like the feelings expressed by brush strokes. As I was creating this work, I thought that black and white was the most suitable.

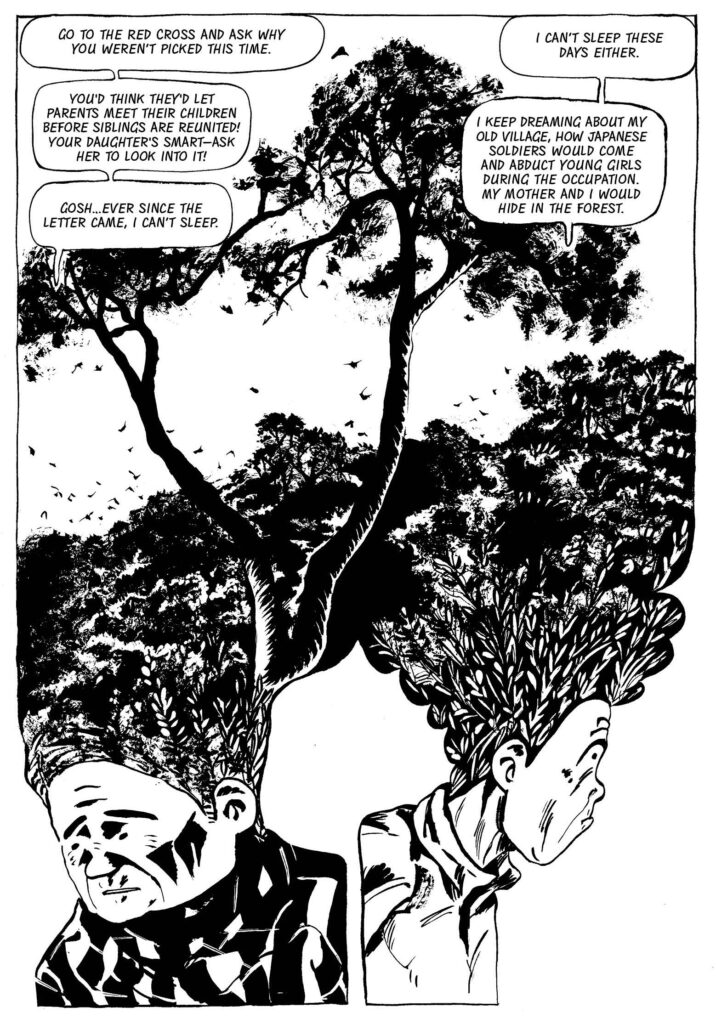

Alexander Chee: I also noticed that you seem to love drawing trees.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes, that’s right. I love drawing nature.

Alexander Chee: This is one of my favorite images in the book. It’s such an extraordinary moment in their conversation. These two women are talking about the possibility of being reunited with their family members. Are trees important as a symbol in this book?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes. Trees often show up in many of our works because of the root network. I lived in France for a number of years and while I was living there, I often found myself thinking about my identity. So whenever I look at a tree, I think about its roots and how that represents a person’s life. It’s a very important symbol for me.

Let’s say the wind is blowing, and if there’s a major event in your life, it seems like the wind is howling and the waves are high, your life has been shaken. And then you experience all these changes. I wanted to convey this using the tree.

Alexander Chee: The use of the tree symbolism is very subtle in The Waiting. No one in the book ever alludes to it. It’s entirely symbolic in the background, kind of a mesh of images. It comes through really beautifully.

I wonder if you remember the first graphic novel you ever read and if that is the one that drew you towards making this kind of art, or if there was another one.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Well the first graphic novel that I read, I don’t exactly remember. I started reading mostly foreign graphic novels. But Korean graphic novels (manhwa) actually made me draw this way, especially the artist Lee Hee-jae. I translated his graphic novel Vedette into French. That was how I came to learn about and feel the sorrow of the characters in it. That process made me realize that graphic art as a medium was really amazing. It doesn’t matter whether you draw well or not. You can convey so much in comics. So I started, and that’s why.

Whenever I look at a tree, I think about its roots and how that represents a person’s life. It’s a very important symbol for me.Alexander Chee: That’s such a beautiful entrance into the form, being able to study it by way of translation.

Both Grass and The Waiting deal with major historical events through the intimate experiences of people who lived through them. Both stories take the reader back and forth between the present and the past, modern day and mid-century Korea. It clearly required extensive research. I know that you visited the places that you wrote about and spoke with people affected by these events. How is research different for a graphic novelist than say an ordinary novelist or a historian? What do you look for?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: When I spoke to these people, I even went to Japan to speak to some of them. I spoke to victims of Hiroshima and I spoke to comfort women, who were subjected to Japanese military sexual slavery during the war.

When I heard their stories, I was so moved and touched, and the experience was beyond anything I could have imagined or gotten out of reading. How could something so horrendous happen to a person? This is not from a very distant past, either. These people are our neighbors. Of course, not everyone shared exactly what they’d been through.

But I realized that quite a few people around me have had these horrific experiences. To my surprise, they don’t end up lost in despair. They remain positive, and hopeful, and have this real desire for life. Through these encounters, I realized just how valuable life was to everyone. It was very moving.

I think even for a fiction writer, the experience of meeting and talking to other people, the piece of listening to their stories, all of that is very important.

Alexander Chee: Can you give an example of some aspect of the story you had imagined that changed after your research? Or do you write your stories after you’ve done the research?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: What I discovered for The Waiting was that it often wasn’t a dramatic moment of separation, but rather very mundane. For some people, the separation happened when they were on their way down south for some reason and they had promised their family they would come back up north. So a father would say to his family, “I’ll come back tomorrow. Stay here with your mother.” But then he would never be able to return.

Sometime after 1968, this man was successfully reunited with his younger brother, who was upset because he thought that his older brother had abandoned them. Both brothers were very surprised to hear the other’s story. It was a great moment of misunderstanding, which was quite common.

Alexander Chee: Would you say it was doing that research that gave you the understanding of how ordinary those separations were? Maybe before doing the research you didn’t understand that it was almost anticlimactic?

If I find a graphic novel particularly touching, then I’ll probably keep going back to it, perhaps every night before I go to sleep, all so that I can relive the moment.Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes. That’s right. They didn’t have to run for cover from bomb attacks or anything. Even after these people came down south, they had no citizenship registration numbers to look one another up, no way to find their family members. Sometimes, brothers and sisters didn’t even realize that they were living in neighboring villages or in the same neighborhood for many years.

Alexander Chee: Wow. The graphic novelist Marjane Satrapi has said of this art form, “I write what I can’t draw and I draw what I can’t write. This has always helped me think of the distinct characteristics of graphic novels, how they differ from prose novels, for example.”

What do you think distinguishes this literary form of graphic novels/comics from other genres, like novels, TV series or even music?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: What I like about graphic novels is that it really strikes a chord with your inner self. It creates a kind of echo. You can linger on even a part of a picture, a single panel, for a very long time. If I find a graphic novel particularly touching, then I’ll probably keep going back to it, perhaps every night before I go to sleep, all so that I can relive the moment.

It’s different from TV, films or music in that it brings out this very calm inner story and allows you to listen to it with your own voice or interpret and analyze it from within yourself. The format of books means you can go back and forth between different pages at your own pace, which I think is also very interesting.

Alexander Chee: It’s that paradox of how the still image somehow seems so alive. Looking at another moment from The Waiting, the mother has met her future husband, and he has no eyes. I was trying to think, “How would I do that?” I use a lot of visual storytelling in my own prose, but something like that is a different challenge.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: About that panel, I was inspired by those Magritte paintings where the faces are draped in cloth. I decided not to draw in his eyes because Gwija, at that point, hadn’t seen her future husband’s face. So that was a symbolic representation of them not having met yet.

Alexander Chee: How do you account for the growing interest in Korean literature in the global literary market?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Well, when I’m reading, I don’t really read because the author is from France or the US. I just like the author. So much of Korean literature is translated. I think it’s a very welcome trend—a positive change. There are plenty of good books that had previously never been translated. Now that they have, it’s becoming easier to reach wider audiences.

There are so many great translators these days. I hope that continues.

Alexander Chee: Janet Hong who translated The Waiting is a phenomenal translator. Whenever I see her name on a translation, I definitely always think, “Oh, I want to get that.”

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Oh thank you, and many thanks to Janet Hong.

Alexander Chee: Part of what moved me about The Waiting was how this novel explores an intergenerational silence that has existed for many years, perhaps hoping to show each generation that this is what the other is going through. It seems that the things that the older generation feels they cannot tell the younger generation or that they hope to protect them from have left that younger generation feeling very distant from the crisis that they are still in.

It’s this painful separation not just of families by the war and the division of the country, but also a separation along a generational divide in a strange way. Was this on your mind when you were putting this story together, trying to repair that gap?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: Yes, of course. Personally speaking, my parents are very old and frail. Were my father still alive, he would be over 100. We have a generation who experienced the Korean war, and those in their 40s through to their 50s who experienced the democratization movement in Korea, and their children, the younger generation of today, who have perhaps little interest in the impact of the war because they haven’t experienced it.

One thing I think should be made clear: Korea is a divided country. The Korean War has not stopped. So in The Waiting, I wanted to look at this universal issue of separated families. I wanted to draw more attention to this defining issue of North and South Korea. I wanted to remind the younger generation, perhaps not for educational purposes, but just to make sure they are aware.

Alexander Chee: I learned so much from this book. It was an extraordinary experience for me, even as much research as I have done, trying to educate myself, both as a writer and as a Korean-American. All these little moments that helped me make some more sense of what happened. So thank you.

When did you first feel inclined to start writing? Like maybe how old were you and are there better times in life to start? When is the right time to begin writing?

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: The first comics short story I made was in 2007. I wrote a story about family separated by the war. And that was my entry point to comics.

__________________________________

The Waiting by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim is available now from Drawn and Quarterly.