Kenny Loggins on How Buck Teeth Saved Him From Vietnam, and the Magic of a Great Audition

Getting Serious About a Career in Music While Avoiding the Draft

Dropping out of school to tour with the Electric Prunes, a psychedelic rock band from the San Fernando Valley, had deeper implications than my ongoing education (or lack thereof). Without course credits to my name, I became eligible for the draft, and was saved from Vietnam only by… my buck teeth.

The late 1960s were the right time for a kid like me to be on the scene. Growing my hair out allowed me to cover up my big ears, leaving my teeth as my primary point of personal embarrassment. Getting braces took care of that. It also took care of the army.

A number of friends from high school had been drafted, and several were killed in action, including our class president. The more I learned about the war, the less sense it made to me. I didn’t support an invasion of a country that was not a threat to the United States. I never saw it as anything close to the moral equivalent of World War II, which had so affected our parents.

When we asked big questions about why we were fighting, we got no answers beyond “this is your country right or wrong—love it or leave it.” If you didn’t offer blind obedience, you were treated like an enemy by the establishment. That made no sense to me. When the National Guard started shooting kids at Kent State, it became a very real issue—of good vs. evil, the old guard vs. the younger generation.

I remember standing in a long line of young men at a pre-induction physical in downtown Los Angeles one sunny afternoon, listening as the sergeant recited a long list of questions designed to weed out the undraftable 4-F losers. “Anyone here with flat feet?” he yelled. “Hernias? Metal in the mouth?” He went on and on, but my attention never left the phrase “metal in the mouth.” What the hell could it mean? The more I thought about it, the more sense it made. There was probably no such thing as an army orthodontist, and since braces were so damn expensive, I figured the military wouldn’t want to be on the hook for replacing them after your service ended.

My childhood braces were long off by that point, but I hadn’t worn my retainer as instructed, and my teeth had begun another slow journey forward in my mouth. It was a perfect exit strategy. I went to my parents, told them I didn’t believe in the war, and they agreed with my stance. Also, they agreed to pay for new braces. I had them reinstalled.

Knowing that hundreds of young men had to show up for those induction physicals in Los Angeles, and having heard that the LA draft board didn’t accept many exemptions, I began to worry they’d somehow learn that my braces were a recent addition. So with the help of a friendly college professor who let me use his address in Fresno, I changed my board to the northern part of the state. Mark Tulin, the Prunes’ bass player, drove me up there in his Datsun convertible. There were only about twenty guys in my group, and sure enough—armed with a letter from my orthodontist—I was given a temporary draft exemption. Luckily for me, when the lottery system was implemented shortly thereafter, my number was so high that there was no way I would be drafted.

I left the braces on until my teeth were straight, which was perfect timing. Just a few months after that I was on the road, touring for the first time with Loggins & Messina.

That would come later, though. Back home following my Prunes experience, I tried to melt back into the scene as seamlessly as possible. I jammed at the same parties I’d jammed at before, and increasingly wondered what I would do with myself. I was still living in my parents’ apartment and going stir-crazy. I felt like an arrow pulled back in a bow, ready to be released. All I needed was a target. It didn’t matter that my time with the Prunes had been difficult; I was readier than ever to commit myself to a career in music.

Enter Colin and Mac. Colin Cameron and Malcolm Elsensohn—a bass-drums duo who were so ubiquitous together that in my memories they appear strictly as “Colin and Mac”—were all over the LA scene. They’d played in Southern California bands for years, backing all sorts of musicians along the way. I first met Mac at the Glendale Ice House after a Second Helping show; I guess he was impressed enough to introduce himself, and I’m really glad he did. He opened some vital early doors for me as I tried to make a name for myself.

Notably, Mac was the one who introduced me to Jeremy Stuart, my conduit to the Electric Prunes. Mac was also the drummer who dropped off of the tour at the last minute, having received a late offer to record an album for Elektra Records with a singer named Diane Hildebrand. Needless to say, Colin was also on that record.

Colin and Mac were my mentors in the world of pro musicians, showing me things like how to prepare for auditions and studio sessions. Seeing my desperation to leave my parents’ apartment, and knowing I had no money for my own place, they let me stay at their pad in East Hollywood for about six months. That was a seminal period. We were either playing or listening to music at all times. I felt like I was finally living the dream.

One night after we dropped some acid, a young woman knocked on the door. None of us had ever seen her before. She looked angelic to me, beautiful in a California way. Best of all, she was holding a guitar. “A friend of mine told me to come and sing my songs for you,” she cooed. Hell yes. We invited her in and she began to play and sing, casting a deep spell over the room. Her songs were part folk, part jazz, and one hundred-percent magic. It was as if Joni Mitchell herself had decided to drop in on a bunch of stoned-out strangers, just to blow their minds. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t Joni, but that’s the kind of impression this girl left.

After an hour or so, she departed as mysteriously as she’d arrived. Somehow, even though everyone in the room was blown away, none of us had the presence of mind to get her name or phone number. To this day, I have no idea who she was. That night might have ended up as the mythology of a collective hallucination had I not asked her to teach me some of her chords, which I used the next day to write a song called “I Ain’t Gonna Stay Here.” I never finished it, but it would prime my jazz-pop pump for many years to come.

One of Colin and Mac’s regular gigs was backing Don Dunn and Tony McCashen, who played together under the name—wait for it—Dunn & McCashen. They were recording an album for Capitol Records, and Mac brought me in to play lead guitar on a few songs. I don’t remember much about the session, except that I wasn’t really a lead guitar player. I mean, I had my moments, but the environment had to be just right, and I had to be feeling it, and then things had to flow—otherwise the possibility of disaster was significant. What Mac suggested—and what I ended up doing—was listening to a demo of their songs the night before the session, and then humming lead guitar ideas into a tape recorder, which I then used to work up my solos.

Another thing that happened during the session was a studio drop-in taking note of my singing during the few minutes he spent in the recording booth. His name was Jim Messina, and he knew a few of the guys in the band. He liked what I was doing well enough to get my name, and then promptly forgot it until we put two and two together some years later while rehashing our histories for an interview.

That session must have gone pretty well, because the group asked me to play lead guitar for them at some of their shows. This might have worked in smaller rooms, but Dunn & McCashen had landed a gig at the Forum opening for Sly and the Family Stone. I was a big fan of Sly, and knew it would be a huge audience. I’d never come close to performing in front of that many people. The Pasadena Civic, where the Second Helping had appeared with the Association, held three thousand people and was half empty when we played there. The Forum held nearly eighteen thousand, and Sly Stone knew how to fill a room.

My theory about auditions is that if I’m not where I belong, I suck. Totally. That’s always been true. I think some part of me just knows when something is right, and that’s when the magic happens.

That gig was like going to the big leagues for me. I wanted to make sure we presented ourselves in a professional way, so when we were working on a new tune of Tony’s, I jumped in and suggested an arrangement. I had an idea for a solo section where each instrument would take one beat to start the breakdown in the middle of the song: Colin would hit beat 1 on bass, I’d hit beat 2 on lead guitar, etc.

Honestly, it was a pretty cool idea, but when it came time to perform it onstage, Tony completely blanked out. He was supposed to be the fourth guy to enter, on rhythm guitar, but he began early, which changed the arrangement in disastrous ways. We all tried to scramble to cover for him. I know now that you have to practice the shit out of an arrangement like that.

That was the final song of the set, the big closer, and it fell apart. As it turned out, that wasn’t the only thing that fell—so did my belt. I really wanted to look like a rock star, so I bought a mock-silver conch belt that I wore low on my hips. Trouble was, nobody told me I should secure it to a belt loop or something, because during my final solo, with the spotlight firmly on me, that damn belt slid down over my hips and around my ankles, and stayed there until the final note of the song.

I was so focused on not fucking up that I didn’t even have the wherewithal to step out and kick it away. It just stayed there like rock ’n’ roll manacles. Don’t think about the belt, I told myself. Don’t think about the belt! This mostly ensured that I did nothing during my solo but think about the damn belt. At least I didn’t try to walk. When the song ended, I quietly bent over and pulled it up enough to shuffle offstage with the rest of the band.

Actually, that belt was a pretty good metaphor for my playing: If I didn’t seriously study my options before showtime, my solos tended to slide downhill in embarrassing ways. I was self-taught, and such an optimist that I trusted my fingers to find their way to whatever amazing solo I was imagining only to discover that I didn’t have the slightest clue how to translate my ideas to the fretboard. I was all about feel. If I was in the zone, or if I’d had the time and self-discipline to work things out in advance, I could usually pull it off.

Too often, though, any good licks I laid down were equal amounts of practice and luck. If I started to think too much about what I was doing, I would panic. It was almost as if I suddenly remembered that I didn’t know how to play lead guitar. I’d get lost, and with minimal technique to find my way back, all those frets would start to look like a corn maze. Way too many of my solos ended up in ashes. I tend to be overly self-critical, but I’m pretty sure I’m not exaggerating here.

I managed to get through that slot opening for Sly, but had less luck with a subsequent show at the Ice House’s other location, in Pasadena, after which Don Dunn pulled me aside and said, “Look, Kenny, you’re way too good to be standing in the shadows with our backup band. You should have a band of your own.” Don was a good friend, and that was a classy way to fire somebody. Also, it was damned good advice.

Still, I kept on trying. I auditioned for a Bay Area band called Sunbear, but got so high while waiting my turn to perform that I could barely speak, let alone play guitar. I auditioned my songs for a spot on the Moody Blues’ label, Threshold Records, but they weren’t looking for my kind of acoustic music. Years later, I met and wrote with Justin Heyward, and he told me the band never heard my audition tapes. Hmmm. Colin and Mac helped land me an audition for Linda Ronstadt’s band. I loved her music—I’d seen her play at the Troubadour a half-dozen times—but for some reason I sabotaged myself by not boning up on her repertoire.

That would have helped, given my inability to read more than a simple chord chart. Linda was sweet and encouraging, but I never had much of a shot at the gig. I think I was mostly hoping for a chance to show her a few of my tunes. Then again, becoming her backup guitarist might have actually been an unnecessary detour from the path I was about to take.

My theory about auditions is that if I’m not where I belong, I suck. Totally. That’s always been true. I think some part of me just knows when something is right, and that’s when the magic happens.

_____________________________

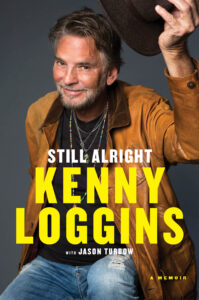

Excerpted from STILL ALRIGHT: A Memoir by Kenny Loggins with Jason Turbow. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Kenny Loggins with Jason Turbow

Kenny Loggins emerged with Loggins & Messina, one of the bestselling musical duos of the 1970s, with their six releases between 1971 and 1976 (plus three live albums and four compilations), counting for 16 million units sold. Loggins has released 14 solo records since then with more than 25 million albums sold, charted five top-10 singles, and won two Grammy Awards for “What A Fool Believes” and “This Is it,” and received one Academy Award nomination for “Footloose.” Loggins’ song “Conviction of the Heart” was hailed as the “unofficial anthem of the environmental movement” by Vice President Al Gore, and his environmental television special for the Disney Channel, This Island Earth, won Emmy Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Writing and for the title track.