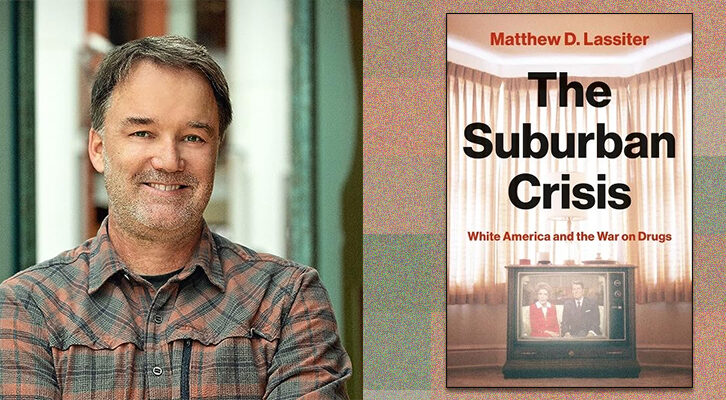

Jhumpa Lahiri on Editing an Anthology of Italian Fiction

The Editor of The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories on the Need for More Literature in Translation

The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories edited by Jhumpa Lahiri, is available now.

*

What was the genesis of this anthology?

Three years ago, I began teaching creative writing at Princeton. I had just returned from Italy, where I had lived in Rome with my family for three years. During that time, I immersed myself completely in Italian literature. Many of the writers I discovered had touched me deeply, and I wanted to share their stories with my students. Unfortunately, I found few English versions of the stories I wanted to talk about (most were outdated, out of print, or difficult to track down). A few months later, during a brief trip back to Italy, I was sitting with a friend (the Italian writer Caterina Bonvicini) and told her how much I wanted to assemble a collection of Italian short stories translated into English. She began pulling books off her shelves and added a dozen more authors to the dozen I already had in mind, and that became my wish list. Then, not long after my second semester had come to an end, Penguin Classics asked me to assemble this anthology.

What were your criteria when selecting these 40 stories?

I cast a wide net and, as is inevitably the case, a somewhat arbitrary one. My aim was to gather together as many of the authors who have inspired and nourished my love for Italian literature, and for the Italian short story in particular. I wanted a volume I and others would be excited to teach from, and that students, ideally, would be eager to read. I wanted to include a wealth of styles, and a range of voices.

The first was to eliminate all living authors from my list. The second was to arrive at a number. Fifty felt celebratory and auspicious, but I worried that it would amount to an unwieldy physical object, and so, with some anguish, I whittled the list down to the forty featured here. Some authors—including several particularly dear to me—were consciously excluded due to one rationale or the other.

I have focused predominantly on the 20th century, though a few of the authors were born and began writing in the 19th, and others remained active into the 21st. It was my priority to feature women authors, lesser-known and neglected authors, and authors who practiced the short form with particular vehemence and virtuosity.

Every anthology bears the imprint of its editor. How does this one bear yours?

The resulting collection, by no means comprehensive, reflects my judgement and sensibility, and also encapsulates a specific moment of my reading trajectory. As I said in an interview in the Financial Times, I see it as a fragmented self-portrait in forty voices that speak to me and for me.

Like me, these writers were all, by and large, hybrid individuals, with multiple proclivities, identities, signatures and shadows. They were writers of fiction and at the same time they were almost always other things: poets, journalists, visual artists, musicians. Many had demanding editorial responsibilities, were critics, were school teachers. Some were professional scientists and politicians. They served in the military, held bureaucratic positions, had diplomatic careers.

You also make the point that they were artists who questioned and redefined themselves over time.

Yes. Some defiantly distanced themselves from earlier phases of their work. Whether linguistic or stylistic, their creative paths were marked by experimentation, by willful mutation.

Speaking of willful mutation, you point out that many of these writers were using pseudonyms long before Elena Ferrante, a pseudonym that has recently taken the literary world by storm.

Some did it for political reasons, either to protect themselves from the law or to disassociate themselves from their origins. Natalia Ginzburg was Jewish and couldn’t publish under her own name. For others, like Anna Banti, a pseudonym was a way to experiment and adopt different identities. Not surprisingly, many of these stories address the theme of identity, of fluctuating selfhood, and accentuate the issue of naming in particular. Many of the writers in this book had conflicted relationships to who they were.

Like you, the vast majority read and wrote in other languages, and the vast majority were also translators.

Yes, they were living, reading and writing astride two languages or more. The majority of these writers shuttled between dialect and standard Italian; though they all wrote in Italian, it was not necessarily the language they grew up speaking, or the first they learned to read and write in or were originally published in. Four were born outside of present-day Italy, and most of them spent significant amounts of time either studying, traveling or residing abroad. A few turned to other languages, writing novels in French or Portuguese, experimenting with German and English, teaching themselves different dialects, complicating their texts and their identities further still. The act of translation, central to their artistic formation, was a linguistic representation of their innate hybridity.

You consider Italy home now, and shuttle between Princeton and Rome. How is your life as a writer different in Italy than it is in the States?

The separation between writers and publishers is less rigid in Italy, and the editorial milieu, more intimate, less corporate than its American counterpart. Tracing its evolution and dynamics is fundamental to understanding how and why so many short stories were written in Italy in the course of the previous century, and in such a rich array of styles. The chronology at the end of this volume operates on two tracks: providing background on the historical and political events that accompanied these authors’ lives, while paying attention to the country’s publishing history as well.

Until recently, schools of creative writing were unheard of in Italy. What has happened in the United States and, to a lesser degree also in Great Britain—the reign of the Master of Fine Arts and the calculated marriage between art and academy—has not yet been sanctioned in Italy, and as a result, most Italian writers still have, by and large, a different center of gravity, either as journalists or scholars or editors, or, in some cases, all of the above.

You write in your introduction that this volume is as much a tribute to the Italian short story as it is validation of the need for translation itself. Explain this.

Language is the substance of literature, but language also locks it up again, confining it to silence and obscurity. Translation, in the end, is the key. Only works in translation can broaden the literary horizon, open doors, break down the wall.

Every language is a walled entity. English is a particularly fortified one. To step outside the Anglophone world is to grow aware of the near-total domination of the English language when it comes to what is being read and celebrated as literature today. The fact remains that Italian writers, for good and for ill, for well over a century now, have looked outside their own literature for inspiration, and the tradition of translation out of English, at least on behalf of Italian publishers, is critical, not peripheral, to the literary landscape.

You write that the Italian language itself is not monolithic, and that any overview like this of Italian literature in the 20th century has to consider the history of the language.

Yes. Italian as we know it was imposed upon a linguistically and culturally diverse population, late in the 19th century, when the separate regions of Italy were unified in the name of national identity.

When you moved to Italy seven years ago, you devoted yourself to reading its literature, in Italian. How does reading a country’s literature help you understand it?

I would say it is the only way to truly understand a country. In literature you enter into the hearts and souls of people in ways no other art form allows.

What do you recommend for further reading?

Enzo Siciliano’s anthology dedicated to the Italian short story in the 20th century was indispensable to me, and I recommend it to those who read Italian and wish to broaden their perception of the short form in Italy. Even for those who don’t read Italian, the index alone, listing all the authors’ names, is the first place I would direct those in search of suggested further reading. To leaf through them is to glimpse the thrilling sweep of the ocean from above, as opposed to navigating the more manageable but partially uncharted bay I have demarcated.

You write in your introduction that your aim was to present a portrait of Italy that reflects its reality, rather than the more romantic version experienced by tourists. What aspects of Italy do you think will surprise readers as they read these stories?

I prefer to work against a reassuring but ridiculous perception encapsulated by an American who once said to me, “Nothing bad can possibly happen in Italy.” Of course, it is one thing to experience Italy as a tourist, another thing to live there. Then again, one has only to read the literature of any given place to recognize that bad things happen to everyone, everywhere.

Fascism and the Second World War loom large in these stories. Did you find they were an overwhelming influence in these writers’ lives, and their writing?

If there is a dominant point of reference, it is the Second World War. The writer Cristina Campo called it “the abyss that had split apart the century.” Indeed, this cataclysmic caesura is what links the vast majority of these authors. The entire 20th century can be read as a battle of wills between the wall Fascism sought to erect around Italy and Italian culture, and those—many of the writers represented here very much among them—determined, despite running grave risks, to break it down. Many lived under Fascism at some point or another, and were affected directly by its legacy. Two were in Nazi concentration camps, and another escaped en route to one. At least a dozen were forced to live, for a time, in hiding, either because they were members of the anti-Fascist Resistance, or because they were Jews.

You have made a particular effort to include women writers, and there are a number of discoveries here—Cristina Campo, Lalla Romano, Fausta Cialente, Anna Banti. What insight did the stories give you about women’s lives in Italy?

Many of these stories are portraits of women, some confronting and challenging patriarchal ideology, others revealing attitudes in which women are objectified, belittled, maligned. One option, on my part, would have been to protest against such stories by omitting them, to protest against these objectionable depictions. But this would misrepresent a society and its history as reflected in its literature. As a woman, and a woman writer, these stories help me to better understand the cultural context of Italian feminism, and to admire the great strides that Italian women have made. The fact of the matter is that many of the most moving depictions of women in this collection were written by men. Marriage is a recurrent theme—to be precise, how a woman’s identity can be altered, compromised and negated by a man, and also by maternity. But the whole of the 20th century, which witnessed the collapse of a series of powerful social institutions, including marriage, was a laboratory in which individual identities were being lost and found, regained and shed.

Many of these writers, like Alba De Céspedes and Luciano Bianciardi, are virtually forgotten in Italy. You mention haunting secondhand bookstores and flea markets in Italy, searching for many of the books by these authors.

It struck me that these 40 Italian authors would not necessarily be familiar to any one Italian reader. Many of them have fallen out of favor, or have been sporadically published, and are therefore hard to come across in Italian bookstores. A few never saw their work published in their lifetime. Ironically, I could only get my hands on them thanks to Firestone Library in Princeton or, if I was lucky, at the Porta Portese flea market, which brings hundreds of secondhand books, every Sunday, to Rome. Even after I had made my choices, people kept mentioning other writers I ought to have included, and suggestions will surely only proliferate now that the book exists.

You say that in immersing yourself in Italian literature, you discovered a “potent, robust tradition of the short form, a harvest far more vast and varied than I’d anticipated.” What distinguishes the Italian short story?

Indigenous to Italy, racconti have thrived for centuries, and they constitute a continuum, cross-pollinating with the world’s literature in ways that the longer Italian form has not. In some sense it is the novel, in Italy, which is the interloper, the imported genre. The roots of the modern Italian short story are themselves hybrid: at once deep and shallow, at once foreign and domestic. There was a period, particularly after the Second World War, when small literary journals, many of them founded by the authors in this anthology, flourished in Italy. They put short stories at the forefront. They were proof of how individually published short stories, free from the economic machinery of book publishing, are by definition autonomous texts: a source of resistance, a means for creative risk and experimentation. Fortunately, there are still talented young writers in Italy who embrace the short form, and once in a while, in Italy as in other places, a short-story collection creeps on to the shortlist for a major literary prize.

You say you ordered these stories in reverse alphabetical order by author’s last name as an homage to Elio Vittorini, whose story appears first. Why an homage to him?

Vittorini was my guiding light as I assembled this book. In 1942, Vittorini published Americana, an anthology of 33 largely unknown American authors—among them, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James, and Willa Cather. But this was no mere gathering of authors; it was a massive, over one thousand pages long, collective translation enterprise, featuring contributions by some of the most important Italian writers of the time, including Alberto Moravia, Cesare Pavese and the Nobel Laureate poet Eugenio Montale. The objective of Americana was to introduce iconic American voices to Italian readers. For America, too, was a fabulous projection in the minds of many Italians of that generation: a legendary place that stood for youth, rebellion, freedom, and the future.

You write, “To leaf through the book today–– is to traverse a bridge that feels nothing short of revolutionary.”

This was no escapist disconnect from reality, but rather, a form of both creative and political dissidence, a heroic, courageous connection, by means of literature, to a new world. The first edition of Americana, published by Bompiani in 1940, was banned by Mussolini’s regime. It passed the censors only after Vittorini removed his critical commentaries on the individual authors, and Emilio Cecchi, a critic in good graces with the Fascist government, wrote an introduction. I followed his example in writing the brief author biographies—intended as partial sketches and not definitive renderings—that preface each story.

You call the short story form by nature “subversive” and “a source of resistance, a means for creative risk and experimentation.“

Fleeting by nature, short stories, in spite of their concision and concentration, are infinitely elastic, expansive, probing, elusive—suggesting that the genre itself is essentially unstable, hybrid, even subversive in nature. It is in homage to Vittorini and to his landmark work—to the spirit of saluting distant literary comrades, of looking beyond borders and of transforming the unknown into the familiar—that I offer the present contribution.

______________________________

The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories edited by Jhumpa Lahiri. Featured with permission of the publisher, Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2019 by Jhumpa Lahiri.