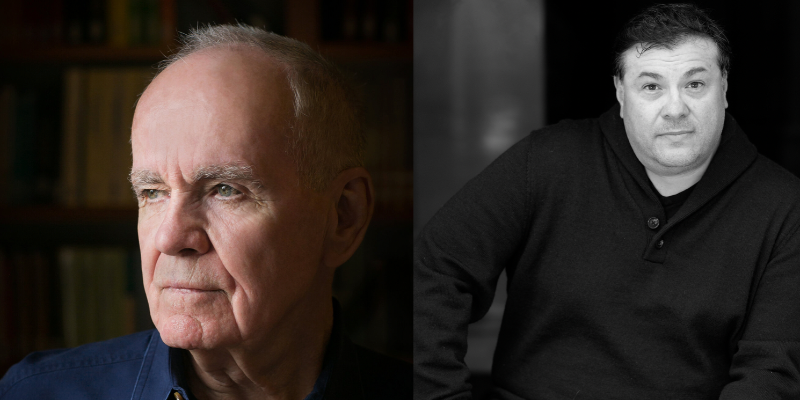

In Memory of Cormac McCarthy: Oscar Villalon on an Iconic Writer’s Life, Work, and Legacy

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Editor and literary critic Oscar Villalon joins V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to celebrate the life and legacy of the novelist Cormac McCarthy, who died last month.

The hosts and Villalon reflect on McCarthy’s vast vocabulary and cinematic descriptions, in which he juxtaposed lyrical prose with graphic violence. Villalon considers McCarthy’s use of regionally accurate Spanish in the Border Trilogy as evidence of the author’s broad understanding of the US’s multilingual diversity. Villalon also reads and discusses a passage from McCarthy’s 1994 novel The Crossing, the second book in the trilogy.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Todd Loughran.

*

From the episode:

Oscar Villalon: I think it’s very interesting that he thought it important to include Spanish in those books. It’s all through The Border Trilogy as well—not just not just in All the Pretty Horses. I think that speaks to somebody who has an understanding of the U.S. that isn’t narrow. Just reading his books he has a grand view, a cosmology of… I guess you would call it menace.

The cosmology of evil versus good. I think that vision allows him to see things differently; it allows him to see things as they are as opposed to the way people want them to be. So what I found thrilling was to say, “Oh, my characters—these Anglos who grew up on the border–would know Spanish. They would be, to a degree, bicultural.”

The late Carlos Fuentes talked about this all the time, about the U.S.-Mexico border being its own thing. I think he had a whole story collection, The Crystal Frontier, that this is a specific region, and a region with its own culture and its own understanding of history. And he reflected that, which I found to be tremendous but also found to be liberating. Because if he can do this, then other folks… Why not you? If you want to employ Spanish or whatever other language you want to employ with English… why not? If it’s integral to the story—if it makes sense.

Whitney Terrell: Roberto Bolaño is the other writer that I think of who wrote about the border but was influenced by McCarthy’s work, like 2666. If you look at the way that the book is written, it seems to me that he’s at least read McCarthy.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Not only did McCarthy pay homage to Hispanic communities, but in Blood Meridian, he covers conflict between Native Americans and the novel’s white protagonists during the Mexican-American War. An article in the LA Review of Books discusses how Blood Meridian is viewed as a “paralyzing critique on the violence of America’s westward expansion.” I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how his work intersects with Native American history.

OV: Well, I don’t know if I could speak to that intelligently, but I’ll say this. Let’s back up a little bit—someone else who I think would agree with this would be Larry McMurtry. The settlement of the West was horrifically violent. It was not an intellectual endeavor at all, but something of just blood and earth. I mean, it was horrific. Killing was lingua franca.

That’s what it was—genocide was the order of the day. And what McCarthy does in Blood Meridian is presents that to us through a filter of what seems to me like almost the King James Version of the Bible. He presents that as biblical, as something almost Old Testament—a deep-seated, ancient evil that is perpetuated upon the land and upon the people.

We could talk about this later, too, but there’s definitely something in his work that speaks to the Apostle Paul and the idea that we are born of flesh. So you’re just damned to sin, you know? There’s a constant fight for redemption, the constant struggle to try to rise above your ugliness. In Blood Meridian, he lays that out in terms of “these guys are getting paid for each scalp, are they not?” As I recall, they’re out there to kill. They’re being paid to kill—both, I believe, by the Americans and by the Mexicans—these Native people.

WT: And what they do–because they’re afraid of Apaches—is start killing Mexicans, scalping them, and then selling the scalps back to the Mexican government. These are all also, notably, ex-confederates. People who are on the wrong side of American history who have been depicted positively in the past being depicted here as agents of pure transactional horribleness.

OV: Yeah, and there’s a sense of—and I will use the word again, because I think this is what it really is—this evil being difficult to extinguish. It rears its ugly head often. And to be in front of it, like with the character the judge, is awesome in the true sense of that word. It inspires awe because the enormity of cruelty—of their capacity to just destroy—is jaw dropping.

WT: The only passages in that book that sort of make me uncomfortable—and they’ve been quoted recently a lot—are the descriptions of the Apaches. They’re described as immensely horrific, weirdly bedraggled… and I just thought that those don’t work for me. I don’t know if those are gonna last that well. And I would think that Native American readers would not like them.

OV: The cloud of dust… the Apaches are described as these monstrous creatures that are coming toward the judge and his troops. Although I will say, too, you could probably make an argument that these are almost like the harpies and that they are now getting their comeuppance, and that this is what it looks like. In other words, maybe not that as being what those people are, but rather as avenging angels—terrible in their fury. Inspiring horror.

WT: The best way to read that passage for me—the most forgiving way—is that they are being seen by these men, and this is how those men would have seen them.

OV: Yeah. Again, I think it should be emphasized, too, that the West he’s depicting is both fictional and real. And by the fictional part, I mean that it does feel biblical. You read that and, to me, it hearkens to reading the Old Testament—the terrible tribulations, the wars among people, the fight for land, etc. It has that mythic quality. So that may be something to take into consideration. It’s this sort of fever dream.

VVG: We’re talking a little bit here about what characterizes his prose, and I think that’s not just in Blood Meridian. I think of so much of his prose as having this biblical force. And Saul Bellow once described McCarthy’s style as “an absolutely overpowering use of language, his life giving and death dealing sentences.” I love this description. So when thinking about McCarthy’s prose, are there other hallmarks of his writing that we haven’t mentioned yet that you think have kept readers with him?

OV: Oh, it has to be the dialogue, doesn’t it? I mean it is just entertaining and delightful. It’s wonderful. It’s hilarious. It’s menacing. I mean, the dialogue, for many people, might be the draw to McCarthy. He’s a great talker. It’s very hard to do on the page, but he is a great talker.

WT: Here’s some dialogue from Blood Meridian—early on, just two people talking. “Kindly fell on hard times, ain’t you son? I just ain’t fell on no good ones. You ready to go to Mexico? I ain’t lost nothing down there.”

OV: You think of the dialogue from No Country for Old Men. The dialogue from The Border Children. All of it has rhythm. It has texture. You could definitely hear the Faulknerian in there; you can hear all sorts of influences. But there’s also just a lot of humor. It has gravitas, too, which is really hard! These sentences carry. Even what you were reading from, Whitney—these lines, which should perhaps be even toss-away lines, don’t feel that way. They feel like they have a lot of balance to them. I read that people said that there were Hemingway influences, and I think if there are, it’s in the dialogue. It’s quick and it’s short, but what’s not being said is huge. And what’s being implied is huge as well.

*

ZYZZYVA • LitHub • “Barbarians at the Wall,” by Oscar Villalon, from Virginia Quarterly Review • Oscar Villalon (@ovillalon) · Twitter

The Orchard Keeper (1965) • Outer Dark (1968) • Child of God (1974) • Suttree (1979) • Blood Meridian, Or the Evening Redness in the West (1985) • All the Pretty Horses (1992) • The Crossing (1994) • Cities of the Plain (1998) • No Country for Old Men (2005) • The Road (2006) • The Passenger (2022) • Stella Maris (2022)

Others:

“Cormac McCarthy, Novelist of a Darker America, Is Dead at 89,” by Dwight Garner, The New York Times • “Cormac McCarthy Had a Remarkable Literary Career. It Could Never Happen Now,” by Dan Sinykin, The New York Times • “Albert R. Erskine, 81, an Editor For Faulkner and Other Authors,” by Bruce Lambert, The New York Times • Paul Yamazaki on Fifty Years of Bookselling at City Lights, by Mitchell Kaplan, Literary Hub • “Crossing the Blood Meridian: Cormac McCarthy and American History,” by Bennett Parten, Los Angeles Review of Books • Oprah’s Exclusive Interview with Cormac McCarthy – Video – June 1, 2008 • Oprah on Cormac McCarthy’s Life In Books • Oprah’s Book Club • William Faulkner • Cormac McCarthy, MacArthur Foundation Grant • City Lights Booksellers and Publishers • The Crystal Frontier by Carlos Fuentes • Roberto Bolaño • Larry McMurtry • King James Version of the Bible/Old Testament/Apostle Paul • Saul Bellow • Ernest Hemingway • Caroline Casey • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 1, Episode 7: What Was It Like to Care About Books 20 Years Ago? • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 1, Episode 24: Oscar Villalon and Arthur Phillips on Getting That Big, Fat Writer’s Advance • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 5, Episode 10: ‘How on Earth Do You Judge Books?’: Susan Choi and Oscar Villalon on the Real Story Behind Literary Awards