In a Quiet London Enclave, Five Iconic Women Writers Forged a Home

Mecklenburgh Square Drew Virginia Woolf, Hilda Doolittle, and Others

In May 1917, T. S. Eliot described for his mother a visit to the American poet Hilda Doolittle, his new colleague on the Egoist magazine. “London is an amazing place,” he wrote. “One is constantly discovering new quarters; this woman lives in a most beautiful dilapidated old square, which I had never heard of before; a square in the middle of town, near King’s Cross station, but with spacious old gardens about it.” Somehow, Mecklenburgh Square has remained a quiet enclave out on Bloomsbury’s easternmost edge, separated from the better-known garden squares by Coram’s Fields and the brutalist ziggurat of the Brunswick Centre. It is bounded by a graveyard (St George’s Gardens) and the noisy Gray’s Inn Road, while its central garden—unusually for Bloomsbury—remains locked to non-residents and hidden behind high hedges. But for D. H. Lawrence, a one-time lodger there, Mecklenburgh Square was the “dark, bristling heart of London.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Mecklenburgh Square was a radical address. And during the febrile years which encompassed the two world wars, it was home to the five women writers whose stories form this book. Virginia Woolf arrived with her bags and boxes at a moment of political chaos; she deliberated in her diaries “how to go on, through war,” unaware that another writer had asked exactly that question in the same place 23 years earlier, as Zeppelin raids toppled the books from her shelf. Hilda Doolittle, known as H. D., lived at 44 Mecklenburgh Square during the First World War, and hosted Lawrence and his wife Frieda while her husband Richard Aldington was fighting in France.

In 1921, three years after H. D. had left the square abruptly for a new start in Cornwall, Dorothy L. Sayers created Lord Peter Wimsey, the swaggering hero of her first detective novel, in the very same room where H. D. had begun work on the autobiographical novel cycle that would occupy her for the rest of her life. From 1926 to 1928, Jane Ellen Harrison, the pioneer of classical and anthropological studies, supported a Russian-language literary magazine from the square, working among a diverse milieu of diaspora intellectuals. And at number 20, between 1922 and 1940, the historian Eileen Power convened socialist meetings to chart an anti-fascist future, scripted pacifist broadcasts for the BBC and hosted raucous parties in her kitchen.

These women were not a Bloomsbury Group: they lived in Mecklenburgh Square at separate times, though one or two knew each other, and others were connected through shared interests, friends, even lovers. H. D. and Sayers lived in the square when their careers had hardly begun, Woolf and Harrison at the very ends of their lives; Power lived there for almost two decades, Sayers and Woolf just one year each. But for all of them, in different ways, their time in the square was formative. They all agreed that the structures which had long kept women subordinate were illusory and mutable: in their writing and their lifestyles they wanted to break boundaries and forge new narratives for women. In Mecklenburgh Square, each dedicated herself to establishing a way of life that would let her fulfill her potential, to finding relationships that would support her work and a domestic set-up that would enable it. But it was not always easy. Their lives in the square demonstrate the challenges, personal and professional, that met—and continue to meet—women who want to make their voices heard.

Though I’ve lived in London all my life, I’d never heard of Mecklenburgh Square until I walked through it by chance one summer evening in 2013. Gazing up at the firmly drawn curtains above H. D.’s weather-worn blue plaque (the only commemoration of any of them there today), I tried to imagine the conversations that had taken place just a few meters away, almost a hundred years earlier. Later, at home, reading about this mysterious square and its illustrious roster of past inhabitants, I was astonished to learn that so many other women writers—some of whose names were unknown to me, but whose lives and work sounded as fascinating as the more famous ones—had made their homes here around the same time. I wanted to know what had drawn these women here, and what sort of lives they’d lived in these tall, dignified houses, where they had written such powerful works of history, memoir, fiction and poetry—often recreating the square itself in their work.

Was their shared address simply a coincidence? Or was there something about Mecklenburgh Square that had exerted on each of them an irresistible pull? They all seemed, on the surface, such different characters, preoccupied by divergent concerns and moving in separate, if occasionally over-lapping, circles—but was there anything fundamental that united them, beyond the simple fact that they had happened to alight, at some point, in this hidden corner of Bloomsbury?

The next time I found myself nearby, I took a detour to Mecklenburgh Square. As I wandered around looking for gaps in the thick hedge through which I might glimpse the garden, I remembered Virginia Woolf ’s famous declaration of 1929: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write.” Turning back for a last glance at H. D.’s balcony as I headed towards Russell Square tube, I wondered if Woolf ’s extraordinary essay might help me understand the texture of these women’s lives here, the prejudices they were fighting and the opportunities they grasped. I began to suspect that what H. D., Sayers, Harrison, Power and Woolf herself were seeking in Mecklenburgh Square was everything Woolf had urged women writers to pursue: a room of their own, both literal and symbolic; a domestic arrangement which would help them to live, work, love and write as they desired. Perhaps, I thought, it was this which attracted them all, in the interwar years, to Bloomsbury: a place already with a literary heritage, close to the British Museum Reading Room and the theatres and restaurants of the West End, where a new kind of living seemed possible, and where radical thought might flourish amid a political atmosphere founded on a zeal for change.

Mecklenburgh Square itself might hold within its history a female tradition of exactly the sort Woolf was looking for.

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf writes powerfully of the way women have been deprived of the conditions, material and emotional, under which artistic work can prosper. For centuries, she explains, women were barred from education and the professions, told that their worth depended on their marital status, and mocked or disparaged for any attempts to express opinions in public, let alone earn money for their work. No wonder, she writes, women’s lives are “all but absent from history.” The essay begins with Woolf on a visit to Cambridge, walking through a men’s college as she waits to meet a friend. The experience solidifies Woolf ’s feeling of exclusion from the scholarly establishment: a productive train of thought is interrupted when she is sternly reminded that the library is closed to women, its stores of knowledge jealously guarded.

But later that day, as she wanders the grounds of a women’s college in the spring twilight, Woolf is struck by the phantom appearance of a bent figure, “formidable yet humble, with her great forehead and her shabby dress,” striding across the terrace engrossed in thought: “Could it be the famous scholar,” asks Woolf, in awe, “could it be J—— H—— herself?” Her vision is of Jane Harrison, the classicist whose groundbreaking work on ancient religion influenced a generation of modernists, and who had died in her home on Mecklenburgh Street just months before Woolf delivered, at Harrison’s former college, the lecture that became A Room of One’s Own.

This ghostly apparition offers the first moment of hope in this dispiriting tale of sneers and locked doors. Fortified by Harrison’s example, Woolf’s despondency shifts to anger, as she investigates the corrosive effect on women’s imaginations of their confinement to a domestic sphere where they were expected to keep quiet, comport themselves correctly and deviate from conventional living arrangements at their peril. “We think back through our mothers if we are women,” writes Woolf, lamenting women’s absence from the canon of literature and the usual narrative of history. Jane Harrison offered a rare model of the sort of intellectual freedom Woolf wanted for women. Born in 1850, Harrison was one of the first women to establish, after decades of rejections and setbacks, a reputation as a professional scholar.

After leaving university, the academic posts she applied for went first to her male peers, then to the male students of her male peers; it was not until she returned to Newnham College, at the age of almost fifty, that she found an all-female community which gave her the validation, time and money she needed to produce the works which made her name—and which paved the way for female writers and public thinkers, such as Woolf, Power, Sayers and H. D. Now, as I examined their books, pored over letters in their archives and started to notice connections between their lives and work, it occurred to me that Mecklenburgh Square itself might hold within its history a female tradition of exactly the sort Woolf was looking for. These five women who lived there between the wars all pushed the boundaries of scholarship, of literary form, of societal norms: they refused to let their gender hold them back, but were determined to find a different way of living, one in which their creative work would take precedence.

__________________________________

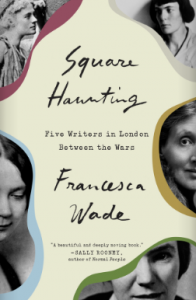

From Square Haunting by Francesca Wade. Used with the permission of Tim Duggan Books. Copyright © 2020 by Francesca Wade.

Francesca Wade

Francesca Wade is the author of Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars (2020). She has received fellowships from the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center, the Leon Levy Center for Biography and the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, and her writing has appeared in The New York Review of Books, London Review of Books, Paris Review, Granta, and elsewhere.