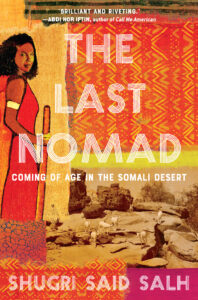

“I Am the Last Nomad.” What It Means to Be the Sole Keeper of a Family’s Stories

Shugri Said Salh on the Transition from Her Nomadic Somali Childhood to Parenthood in California

I am the last nomad.

How can I be the last one? Nomads still exist in that faraway desert where I grew up, so how can I make such a bold statement? What I am really trying to say is, I am the last person in my direct line to have once lived like that, and now I feel like the sole keeper of my family’s stories. As I sit here in my home in California, weaving my tale for you, the weight of that responsibility urges me on. All of my ancestors on both sides of my family were nomads; they traveled the East African desert in search of grazing land for their livestock, and the most precious resource of all—water. When they exhausted the land and the clouds disappeared from the horizon, their accumulated ancestral knowledge told them where to move next to find greener pastures. They loaded their huts and belongings onto their most obedient camels and herded their livestock to a new home.

My nomadic family was at the mercy of the weather. At the end of jilal, the long dry season, when the clouds finally rumbled with rain, we looked up at the sky with renewed hope. As the desert quenched its thirst, the red earth crackled back to life. Responsibility eased, adults welcomed the rain with drums, singing, and dancing. Children got fat and healthy. Sitting around the fire at night, they soaked in the folktales and poems passed down from generation to generation. But despite the renewed abundance of food, we knew we had to preserve some of it for the dry season to follow. Sometimes, the drought hit harder than usual, killing both livestock and people. Bones and twigs soon littered the terrain where goats and sheep once happily grazed. In those times, my ancestors ceased singing under the moon, their drums hardened, and they longed for good news. Children no longer heard stories by the fire, and an old poet would bellow to the desert, voicing his agony. He would speak of a dying land taking his precious camels. His mournful poem would then travel through time and across borders, to remedy the pain of his people for years to come.

My three children, raised in California, know nothing of nomadic life except from the stories I have shared. As I sit here now in my comfortable suburban home listening to my teenage son excitedly tell me about his favorite YouTuber, I am reminded acutely of the void between my past and my present. I speak of a world of which he has little understanding. An old African proverb says, When an elder dies, a library is burned. I am not yet an elder, but I do feel like a portal between two worlds. I am the last person in my immediate family who holds this particular library of knowledge. As the years pass, the sense of urgency I feel about sharing my experience with my children and the world grows.

In my imagination, I have shared my story with each of you many times as we gathered under a clear black sky, its shiny stars guiding my ancestral wisdom. I have imagined you leaning in to me, as if I had brought news of water after a drought. I have poured us more tea, for I knew it was going to be a long night under the luminous moon; I wanted to get this tale of mine right. The fire between us has crackled with excitement, as if to nudge my story along. But now it is no longer enough for me to just imagine telling you my stories; I feel the need to bring you all to the fire and into my world.

Stories have always created understanding and connection between humans. In this era of great misunderstanding, I wish to help rein us back in to our shared humanity. The beauty of my culture was imprinted on me when I was very young, and I cherish it so deeply that my desire to share it only grows. Like an archeologist desperately excavating a forgotten world, I want to bring the details of my nomadic upbringing to life before it is lost forever. I don’t want the library of my past to die with me. The resilience I learned from surviving life in the desert carried me through the unexpected death of my young mother, being chased from my country by civil war, and defying my clan’s expectations after I dared to fall in love with a man from the “wrong” country. Though I was torn from nomadic life too early, it gave me a strong foundation and anchored me to that world despite the tumultuous twists and turns that followed.

I sometimes experience visions of my nomadic life here in California, despite the 20-plus years and thousands of miles of distance between me and my homeland. Am I trying to assuage a longing left unfulfilled, or do these visions exist to keep me grounded and remind me of my roots? Just the other day, as I was sitting in the sun in front of Whole Foods eating sushi, a woman passed me carrying an African-style basket and an empty plastic water jug. Instantly, I was standing in front of my desert hut, eyes fixed on the scorching terrain, waiting for a glimpse of my uncle to appear, leading our camel back from collecting water. Water was often a day away, sometimes more, and the wait was trying on my young body. I actually laughed out loud at how odd it was for someone to be fetching water in a place where it is just a faucet away.

All of my ancestors on both sides of my family were nomads; they traveled the East African desert in search of grazing land for their livestock, and the most precious resource of all—water.Certain stretches of highway that meander through the hills and valleys near my Northern California home always remind me of the lands where I once lived. My innate compass guides me as easily through this maze of roads and highways as it did through the endless, unmarked terrain of the desert. Driving one day, my eyes scan the horizon as I’ve always done, in an instinctive search for danger. No lions or hyenas, but I spot a car ahead of me swerving erratically. As traffic slows around me, my eyes settle on the golden, dry grass and the scattered green trees, mimicking the landscape of my past. Suddenly, I see myself sitting under an acacia tree with my herd of goats, vigilant in my mission to protect my precious animals from hungry predators as I wait for the heat of the midday sun to abate.

As the traffic resumes its pace and I drive on, my thoughts deepen and I ponder the journey my life took to bring me to this very road. I begin to shake with laughter. The man driving the car next to me stares at me like I’m crazy. You have no idea who I am or where I come from, I think as he speeds away. Dear Strange Man, I am laughing in the comfort of my minivan, not because I am crazy, but because my journey to this highway began so very far away. It is ironic that I, of all my mother’s nine children, am living this life. My mother’s plan was for me to live permanently as a nomad, to be my grandmother’s helper. Right now, I should be married to an old nomadic man, leading a nasty-tempered camel through the desert in search of water. If I failed to birth him sons or showed any signs of aging, he would not hesitate to take a younger wife. Despite my love for the culture and traditions of my youth, the guiding force of my grandmother, and my occasional longing for that simpler way of life, I am thankful for the life I have today.

My mother and father came from a world governed by a complex, conflict-filled clan system and the importance of your line of forefathers. A world where warring clans gave each other their young, virginal daughters to create allegiances and hoped-for peace. Could my parents ever have imagined a world where their desert daughter laughed with joy while skiing down a snowy mountain or drove endless hours to take her children to soccer practice, dance class, gymnastics, or simply to play with their friends?

As a teenager, my father left his family in the deserts of western Somalia, despite his mother’s objection. He traveled a thousand kilometers, to Dire Diwe, Ethiopia, to get an education, and he never looked back. While visiting his nomadic sister decades later, my father spotted my 15-year-old mother herding her goats, her brown skin shimmering with the tone of the very desert she sprung from. He was instantly smitten by her beauty, but when he asked to take her hand in marriage, her mother refused. The men of her clan intervened, my grandmother relented, and my mother moved to the city with him.

My young mother found it more painful to disentangle herself from nomadic life than my father had. She was close to her mother and still wanted to be near her. She visited her mother often and sent each of us to stay with her mother—our ayeeyo—from time to time, usually during the rainy season so we could get fat and healthy. When I was a baby, my grandmother carried me on her back as she herded her goats and sheep, singing me old lullabies as she walked. As I got a little older, I sat by the fire while she told me stories and recited poems. My ayeeyo was a tall, regal woman who kept me close at night while the calls of lions and hyenas echoed in the distance. From my earliest childhood, my ayeeyo taught me how to be brave and resilient.

Because my mother had moved away, she felt it was her duty to provide a helper for her aging mother. In a society that saw daughters as a burden, I was my mother’s fourth girl. Early on, she realized she would have to sacrifice one of her daughters to help our ayeeyo. I was that daughter, the chosen one. I would not grow up in the city with the rest of my family. I would not get an education, despite my father’s wishes. I am the last nomad.

__________________________________

From The Last Nomad © 2021 by Shugri Said Salh. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.