How to Read Caves

From Tennessee's Tuckaleechee Caverns to the

Caves of John Keats, Virgil, and Virginia Woolf

When I was a kid, I went on a class trip to Moaning Cavern in the Gold Country of California. Moaning Cavern. The name was horrifying: the sense that this place moaned, that it had a voice. We had to walk down into the earth, down a metal spiral staircase that was enclosed like a cage, and I was sure that the stairs would collapse, and I would fall, just like Alice in the rabbit hole, her pale blue skirt billowing out into a parachute, into nothing. In the cave, we saw old animal bones and rock formations. I felt trapped, and the only way out was back up the spiral staircase. Now it is called “Moaning Cavern Adventure Park and Zip Line,” which does not sound threatening at all. But the staircase it still there: 235 stairs, 165 feet down. It doesn’t seem like much. The numbers don’t account for it.

In Endymion, John Keats wrote that a cave is a place of despair beyond the limits we imagine for the soul:

There lies a den,

Beyond the seeming confines of the space

Made for the soul to wander in and trace

Its own existence, of remotest glooms.

Dark regions are around it, where the tombs

Of buried griefs the spirit sees, but scarce

One hour doth linger weeping, for the pierce

Of new-born woe it feels more inly smart . . .

(Book 4, lines 513-20)

Keats’s Cave of Quietude is interior to the self, but it is also a place where you can wander. It is a place of extraordinary sadness, of melancholy, of glooms that are both yours and remote—far from you. It is a place of sleep and death and the wish for death, of quietude and contemplation and the freedom from contemplation. It is a place where the soul traces its limits and feels them out, like a kind of searching and mapping. It is beyond all “seeming confines,” and it is itself a seeming confine. It is a place you can stay and dwell, a place hidden and secret. “Happy gloom! / Dark Paradise!” Keats writes (lines 537-38). A place of opposites. It is silent and articulate, the entrance ravaged by “woe-hurricanes,” but “still within and desolate” (lines 527-28). And the buried griefs, like cave formations, are always growing, always becoming more than themselves.

This cave is dedicated to your sorrow and pain. A “native hell,” he calls it: “ . . .the man is yet to come / Who hath not journeyed in this native hell” (lines 522-23). It is of you—native—and not of you: a hell, another place. The cave is a void, a lack that you can fill with your woes. It is what you feel in your chest, where you feel the worst things. “My hearts aches,” he writes in “Ode to a Nightingale.” This is not figurative, or at least it is not only figurative. It is actual. A physical thing, not an abstraction or a thing of the mind. He means that his heart aches, and that is his cave. There it is, he says. Over there. Here. Walk around. That is the Cave of Quietude.

“A cave is a place where the soul traces its limits and feels them out, like a kind of searching and mapping.”

So caves are sorrow, and caves are terror. And yet somehow, on a warm afternoon, I find myself in the souvenir shop of Tuckaleechee Caverns in Townsend, Tennessee, surrounded by shelves of figurines, waiting to go down into the earth again. I have bought my ticket. I pick up a rose-colored stone bear. He is cool to the touch, his face a series of angles, not round like a bear at all. There are also stone dolphins, turtles, and fish arranged in rows on the shelves, but these animals seem out of place, as if they have lost their way. I rifle through baskets of rocks and arrowheads for children. Some rocks are placed in little white boxes with cotton padding, like jewelry. I walk past sharks’ jaws and painted wooden ducks. Dreamcatchers and stained glass panels of mountain landscapes hang above me. According to an old brochure from the 1960s, the gift shop is “cooled by caverns.” Although this looks like any souvenir shop, it marks an opening in the ground.

Located right on the edge of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the town of Townsend is known as “the quiet side of the Smokies.” It is home to about 500 people and hosts many more during the tourist season. I stumbled on it years ago, and now I go there often. I drive from central North Carolina, picking up the 441 in Cherokee and heading through the park, up to the North Carolina-Tennessee line, where people stop to pose for pictures in front of a plaque set into a rock. 5,046 miles above the sea. Not all that high, but the Smokies don’t care much for height—not height on the scale of mountains out West. Their mountain-ness comes from something else. Sometimes I stand at one of the overlooks and watch the sun cut patterns in the green-gray distance, triangles like windows in shades of shadow. And then I continue along, descending into Tennessee, the two-lane highway hugging the Little River into town.

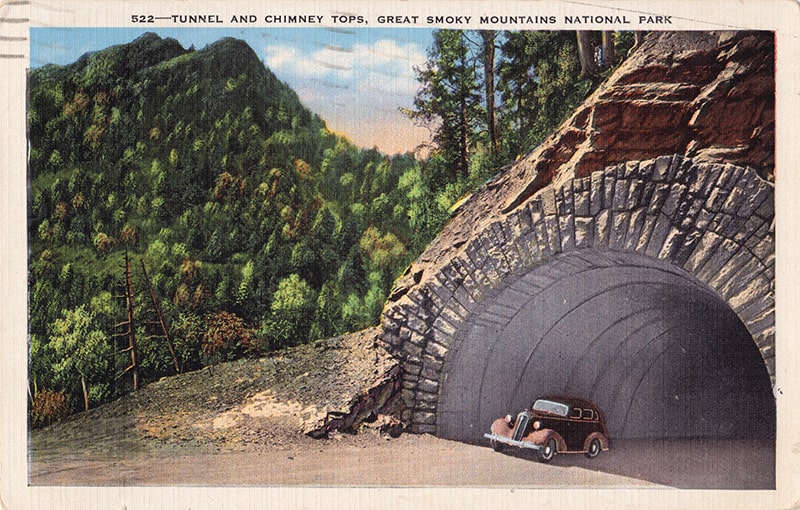

A vintage postcard from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

A vintage postcard from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Seventeen miles down the two-lane Highway 321—past the wood carving place where you can buy trees and bears, on the other side of Wears Valley—is Pigeon Forge, home of attractions including Dollywood, the Pigeon Forge Gem Mine, the Hatfield McCoy Dinner Show, and the Biblical Times Dinner Theater, which bills itself as “The #1 Christian Dinner Show in Pigeon Forge.” If Pigeon Forge and neighboring Gatlinburg serve up endless copies of the Smokies, a barrage of nostalgic mountain mythology, Townsend offers visitors the national park itself. No spectacle. There are barbeque joints and family-style restaurants, a train museum, the Great Smoky Mountains Heritage Center, a dulcimer store, and tubing businesses and motels. The place where I always stay is on the side of town closest to the park, right past the KOA. There is an old rusty LODGE sign out front. The town is silent after about 9 p.m., and few cars pass through at night. There aren’t many lights, so when it’s clear, the sky looks like a planetarium, and the air smells of campfire.

There is a big sign for Tuckaleechee Caverns on the other side of town, but you have to drive a few miles further to reach it, past two churches, a cemetery, the Davy Crockett Riding Stables, and through green hills. The red building trimmed with white resembles a Swiss chalet. The caverns are open from April to October, the high season in the area, and then they close for the winter, as does most of the town, hibernating like a bear.

![]()

There are caves, and then there are caverns. Both are formed naturally by the weathering of rock. But a cave is any cavity in the ground large enough that a portion of it doesn’t receive direct sunlight: a hollow in the earth with an opening, either horizontal or vertical. There are all sorts of caves, including ice caves, sea caves, volcanic caves, and glacier caves. Caves formed by the wind are called “Eolian Caves.” They are named for Aeolus, the Greek god of wind, and Aeolian harps—beloved by poets from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Henry David Thoreau—are instruments played by the wind. Maybe the wind makes a sound as it carves out a cave like this, as it does on the harp. But a cave is a lesser thing than a cavern. A cave can only be a cavern if it is large, underground, and can form speleothems, or cave formations. Caverns involve many caves that are linked to one another by passageways. They are caves, plural. And they are not so obvious as caves. They may not have openings; sometimes their entrances must be created.

Caverns need to be discovered, or at least rediscovered. They are lost things, things hidden in the earth that may or may not be there. I have never been to Lascaux in the Dordogne, but I like to think about it, decorated with paintings of animals made with pigments and minerals mixed with animal fat. Made with animals. It was discovered—or found again—by teenagers in 1940. Imagine stumbling on a cave filled with Paleolithic paintings. I wonder if they ever got over it. As its website indicates, Luray Caverns in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley was “found” in 1878, but the caverns contained human bones and a skeleton believed to belong to a Native American girl. The men who came across it had noticed a protruding limestone outcrop. They dug for hours and then slid a rope down and explored by candlelight. Likewise, the Cherokee knew about Tuckaleechee Caverns long before the white European settler-colonizers of the area, as another old brochure notes: “A secret the Cherokees discovered.”

Detail from the cave paintings at Lascaux.

Detail from the cave paintings at Lascaux.

Tuckaleechee Caverns is less famous than Luray Caverns or Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, the longest cave system in the world. According to the National Caves Association, there are are over 8,000 caves in Tennessee: more than one-fifth of the known caves in the United States. Tennessee is a land of caves, but most are not open to the public. Tuckaleechee opened briefly in 1931 and then closed during the Depression. The original owners W.E. Vananda and Harry Myers had explored in the cavern as boys, sometimes scooting along on their bellies. They carried kerosene lanterns fashioned out of soda bottles. When they were students at Maryville College in the late 1940s, they talked about opening the caverns, and after years of working construction jobs in Alaska to raise the funds, they opened in 1953. Electricity wasn’t installed until 1955.

![]()

The man who sold me my ticket walks up to me. “The tour is ready to start,” he says. “It’s this way.” I put down the souvenir arrowhead I have been examining and follow him into another room, past postcards and a wooden rack of books about the Smoky Mountains and glass display cases filled with stones and minerals. A dozen of us gather at the entrance to the caverns and await instructions from our guide, who introduces himself and beckons us inside, down some stairs and along a concrete path.

“Are there any stalactites or stalagmites in this cave?” a man ahead of me asks, and the guide says yes, there are.

“Stalactites are the ones that come down, and stalagmites come up, right?” he says, and the guide says yes, that’s right.

I feel compelled to duck as we walk along the pathway, even though I don’t need to. The ground is slippery, so I hold the pipe railing, which is reinforced in places with heavy black tape. The caverns’ stairs, bridges, and walkways were all originally wood, but in time they molded and had to be replaced by concrete. Vananda and Myers carried in the sand, cement, and gravel themselves and worked, just the two of them, for four years, to build the new walkways. I think about them exploring this space as children with no walkways or proper light. Now there are cables and lights strung throughout.

The tour of Tuckaleechee Caverns covers a mile, but as I walk it, I lose all sense of distance; I can’t trace it as Keats could trace his Cave of Quietude. I don’t know where its borders are, where its limits are located. There is no distance in a cave, or at least not under your feet. The distance is above and around and always shifting. The height of the ceiling, the space between walls. These things are not set.

We walk along a stream that runs the length of the caverns, and I put on my sweater as it is a little cold, and the cold is wet and heavy. A few people walk up to the stream and look down into the water. The guide tells us that as kids, Vananda and Myers kept to this stream as this was the only way to know where they were. It kept them from getting lost. If they had set off in any direction, they might never have found their way out. I squat down by the rocks that the water runs over, each one flat and smooth like sea glass, and our guide’s flashlight flickers over the surface. He says that we can drink the water, that it is absolutely pure and untouched by anything, so I take a mostly-empty Poland Spring bottle out of my purse, drink the rest of the water in it, and fill it up.

“There is no distance in a cave, or at least not under your feet. The distance is above and around and always shifting.”

A woman next to me turns to her friend. “No way am I drinking that,” she says. Her friend laughs.

I take a few sips, and the water seems somehow different from normal water, although I don’t know how. One small pool has been turned into a wishing well. The coins look like part of the stone and blend together in a patchwork of copper and silver, reflecting the artificial lights. Things from the world above. The dragon in Beowulf lives in a cave and hoards things from the outside world. The things in his treasure trove are valuable to humans, but they are not valuable in the same way to the dragon. The dragon is an outsider, like Grendel and his mother: figures who attempt to destroy this world that excludes them. Maybe the dragon loves his treasures. In the end, he is killed and pitched over a cliff into the sea.

In this real cave, I see only fictional ones. Invented places. Its stone is the stone of books.

Epics love caves. In The Odyssey, the Cyclops’ cave is also filled with temptations. Odysseus and his men come upon it when the Cyclops is away:

So we explored his den, gazing wide-eyed at it all,

the large flat racks loaded with drying cheese

the folds crowded with young lambs and kids,

split into three groups—there the spring-born,

here the mid-yearlings, here the fresh sucklings

off to the side—each sort was penned apart.

And all his vessels, pails and hammered buckets

he used for milking, were brimming full with whey.

(Book 8, lines 244-251)

Odysseus’ men help themselves to the Cyclops’ store, which he does not appreciate. He murders many of them—“knock[ing] them dead like pups” (Book 8, line 326)—but more terrifying than this is his closing up of the cave. Before he goes on his violent rampage, he hoists a boulder—“a tremendous, massive slab” (Book 8, line 272)—in front of the entrance, trapping them inside. His cave is a home, but one that offers no hospitality. It is a home where visitors’ brains are dashed out, and blood soaks the floor. And this is not the only cave Odysseus encounters. In Book 9, Calypso tries to hold him back “deep in her arching caverns” (line 35). He compares the cave—and this holding him back, this desiring him for a husband—to Circe. Like Circe’s palace, Calypso’s cave is a place where the hero can lose himself, his memories of home, and his sense of duty. It is a false home, a dangerous simulacrum that invokes the absent home of Ithaca, a place to which Odysseus must return, but a place he returns to slowly, often losing his way.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, Aeneas also loses his way in a cave—for a time:

Now to the self-same cave

Came Dido and the captain of the Trojans.

Primal Earth herself and Nuptial Juno

Opened the ritual, torches of lightening blazed,

High Heaven became witness to the marriage,

And nymphs cried out wild hymns from a mountaintop.

That day was the first cause of death, and first

Of sorrow. Dido had no further qualms

As to impressions given and set abroad;

She thought no longer of a secret love

But called it marriage. Thus, under that name,

She hid her fault.

(Book 4, lines 227-38)

But I don’t see Aeneas in this cave or in my Tennessee cave. I see Dido. What happens between Dido and Aeneas in this cave is “the first cause of death” for her. It is a place of profound joy, but in an epic where the founding of nations is what matters most, the binding together of hearts and bodies will not hold. The happiness of their non-marriage marriage is circumscribed, as is the cave itself. The cave is the origin of Dido’s sorrow, a place where she can say: Yes, there it is. That is where it all began. Like Keats’ cave, it belongs to her, but it is also a place apart. The cave is not quite real, so everything that transpires in it and everything that it makes possible—the end of desire, and the beginning of it, too—will not last.

In this way, her cave is a place of freedom. Dido gets away from her author in the cave. She presses beyond the limits that he impresses on her. What happens in the cave remains hidden. Not private, certainly—the gossip in Carthage proves that—but shrouded nonetheless, like a curtain is drawn over it, like the cave is beyond the epic itself. Virgil’s Dido is a madwoman, a woman who destroys herself. But before she is his madwoman, she is Dido in the cave, with her desire, all of it, filling the space like Keats’ sorrow, before he can turn her into what he needs her to be. You can get away from things in caves.

![]()

Somewhere in Tuckaleechee Caverns, the sound of dripping water keeps the time, although I don’t know what time it is. A waterfall falls out of a crevice above that floods with light but seems to lead to nowhere. In the “Big Room,” which was discovered in 1954 by members of the National Speleological Society, we admire stalagmites that are 24 feet high. Monsters. The room is more than 400 feet long, 300 feet across, and 150 feet deep. Our shadows mark the walls.

“We call that one the Totem Pole,” says our guide, gesturing at one of the stalagmites. “And that’s the Dinosaur’s Toothpick.” He pauses and smiles. “But if you’re from Florida, it might be a gator.”

The word “room” suggests that a cave is a house, but not the kind you can paint, wallpaper, or decorate with mid-century modern furniture. In fact, enormous piles of odorless bat excrement in the Big Room remind you that this is no ordinary room. “They made gunpowder out of it during the Civil War,” our guide says. “We have bats the size of a thumb down here. Sometimes they get into the gift shop and sleep on the ceiling.”

The Big Room was opened to the public a year after its discovery—the same time that electric lights were added to the caverns. Under some of the bulbs are small ferns. Plants only grow in the artificial lights. When the cave is closed for the winter, the moss dries up.

Our guide says that he’s going to show us what it’s like in the dark, and everyone feigns fear. Or perhaps not.

“It’s darker than death,” he promises, walking over to an electrical panel and flipping some switches. The lights go out, and everything is gone. It smells like stone.

“It’s like your eyes don’t work anymore,” a woman next to me whispers. I think that she has leaned over because I feel a motion in the air, but I don’t know.

“It is,” I say, in case she is talking to me.

Once he turns the lights back on, we head back along the stream, passing columns formed when stalactites and stalagmites meet, having grown towards one another, slowly. The speed at which the water drops down determines the shape of the formations, so the water shapes the stone. If the formations are wet, they are still growing. Some look like caramel-colored fans. Others are tan fingers that beckon you somewhere unknown. A man walks over the wall and touches a lumpy, glossy rock. “It looks like a brain,” he says, eyeing the yellow, mossy goo that traces the contours of the stone. Another formation is a “chandelier,” and others are “drapery formations.”

“Maybe a cave is a place where the right words for things escape us and settle somewhere in the stone, in limestone grooves, because they don’t want to be seen or known.”

“The stalactites look like castles,” a woman says. “Or rockets.”

Caves are places so strange that they can only be accounted for by comparison. Stalactites also look like:

Icicles (so everyone says)

Teeth

Frosting

Dripping paint

Knives (or spears?)

Bangs (in the sense of hair)

Rope

Mushrooms

Tubers

Carrots

Mold

Pencils

Tentacles

Stovepipes

Cacti

Lanterns

Capillary tubes (stole this from the tour guide)

Jellyfish

Caves are places where things are like, not where things are. The formation known as “Chandelier” is also called “Palette” as it resembles an artist’s palette. These are such different objects, and neither quite accounts for the formation, so both are needed. All these words remind you that nothing is right. These comparisons plunge you into a figurative world, a world of language. What is a cave, and what are its limits and the limits of its language? Maybe a cave is a place where the right words for things escape us and settle somewhere in the stone, in limestone grooves, because they don’t want to be seen or known—they just want to be there—and maybe it is the constant drip of water that keeps them alive in a dark place, away from the sun, and maybe that is where they like to live best, apart from showy things and their showy need for light.

Virginia Woolf saw the writer as a maker of caves. Caves are imagination itself, how the author creates. On August 30, 1923, she wrote in her diary about Mrs. Dalloway, which had the working title of The Hours: “ . . . I have no time to describe my plan. I should say a good deal about The Hours, & my discovery; I dig out beautiful caves behind my characters; I think that gives exactly what I want; humanity, humor, depth. The idea is that the caves shall connect, & each comes to daylight at the present moment.” These caves aren’t necessarily visible to the reader, not as such. They hover behind the characters, making them what they are and imbuing them with humanity. And they connect and come to daylight: this is the nature of one character’s connection to another—the connections of caves, the passageways between them. The author carves out caves as water does, generating voids that she can manipulate, shape, and fill. On October 15, she wrote more about this discovery: “ . . . It took me a year’s groping to discover what I call my tunneling process, by which I tell the past by installments, as I have need of it. This is my prime discovery so far . . . ” Her tunnels tunnel behind characters, between characters, and into the past.

In time, we come up out of our tunnels, into the lights of the souvenir shop, and everyone thanks our guide for the tour and disperses, heading for their cars. I walk around the shop again, picking up the same fake arrowheads. Outside, the day is warmer than the cave, and the sun is getting low.

Susan Harlan

Susan Harlan is a writer based in Winston-Salem, NC, who is particularly interested in the relationship between place, memory, and objects. Her essays have appeared in publications including The Guardian US, The Paris Review Daily, Guernica, Roads & Kingdoms, Racked, The Morning News, The Awl, Curbed, Atlas Obscura, Nowhere, The Common, Literary Hub, The Bitter Southerner, The Brooklyn Quarterly,and Public Books. She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature from New York University and an M.A. in English Renaissance theater history from King’s College London and teaches English at Wake Forest University. Her book Luggage was published in the Bloomsbury series Object Lessons in March 2018. And her book Decorating a Room of One's Own, a humorous mash-up of home design reportage and literary homes based on her column for The Toast, was published by Abrams in October 2018.