How Stephen Miller Abandoned the Lessons of His Jewish Ancestors

Fleeing Pogroms in Russia, Miller's Mother's Family Escaped to the US

Stephen Miller’s earliest years were choreographed mostly by his mom, who took care of him and his siblings at home. He learned to play percussion, including a marimba. They occasionally traveled to Miriam’s hometown of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. They rode the Inclined Plane, a cable-traction funicular for rescuing people from floods by carrying them up a large hill. Stephen learned his maternal family history. “He was inculcated in his heritage and the story of his immigrant forebears,” recalls Richard Burkert, president of the Johnstown Area Heritage Association.

Decades before, Stephen’s maternal grandmother, Ruth Glosser, had decided to record the family history in a 47-page document, completed in 1998, “A Precious Legacy.” Ruth dedicated it to Izzy, her husband and partner in crime, who taped relatives’ recollections. “Some may ask my reasons for devoting the time and energy necessary to compile a family history. Why bother? Who cares? . . . [Our family] survived the worst two anti-Jewish excesses of the twentieth century—the pogroms which took place in the Russian empire and Russian-held Poland, and the Holocaust which exterminated six million Jews during World War II. They survived because they emigrated . . . to remember is to defy the objectives of the czarist regime and the Nazis.”

She believed her generation was “the bridge between the past and the future,” and felt a responsibility to help her kids and grandkids remember their great-grandparents: “The ones who came to this country with virtually nothing but the clothes on their backs . . . the generation who all their lives spoke English with the trace of a Yiddish accent.”

Wolf Glosser was Stephen Miller’s maternal great-great-grandfather. He was born in a town of marshes and forests, Antopol, in what is now Belarus. He and his family lived in a small house with a thatched roof and a dirt floor, no plumbing. One of Wolf’s daughters, Bella, recalled: “I was always scared.” The Jews were being scapegoated for political and economic instability in the region after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. “Between 1903 and 1906, pogroms were perpetrated in 64 towns and 626 townlets and villages. Thousands of Jews were slaughtered,” wrote Ruth. The Glossers lived in fear that they were next.

Armed Cossacks galloped through on horseback, and peasants who visited the shtetls to conduct business mimicked the Jews’ speech and sicced their dogs on the children. “Under the instigation of nationalist agitators or zealous local clergy, such confrontations would occasionally turn into public ‘blood’ accusations, collective attacks on Jewish shops, and, ultimately, full-fledged pogroms,” wrote Ewa Morawska in her history of small-town Jews at the turn of the century, Insecure Prosperity. Wolf asked the local rabbi for advice. According to Ruth: “[He] urged people ‘(with the help of God) to take things in their own hands’ . . . and emigrate to America, ‘Go . . . you will make a living there,’ adding, ‘Observe the Sabbath.’ ”

Wolf arrived at Ellis Island on January 7, 1903. He peddled bananas in New York City and changed his name to Louis. “One of the main things everybody wanted to do when they came to America was become Americanized,” recalled his grandson Izzy. Louis’s oldest son, Nathan, came and found a small Pennsylvania town that appealed to him, called Johnstown. He found a job as a tailor, and soon bought the shop when a Jewish neighbor lent him money on a handshake. Johnstown was becoming one of the nation’s top steel producers. Every day, the steel mills rained ash on the red-hued community, cradled between verdant hills and the Conemaugh and Little Conemaugh rivers.

All their lives, the Glossers would strive to help the poor and persecuted.Louis and Nathan expanded the store to sell secondhand clothing. They sent for Louis’s wife, Bessie, and their unmarried children. By the 1920s, the family business became a full department store: Glosser Bros. It marketed itself as the “working man’s friend” with the “lowest prices.” They sold trunks, which migrants shipped full of gifts to loved ones in the Old World, including portraits of themselves in nice outfits, encouraging family migration. Every afternoon when the mills closed, masses of dusty-faced men poured out in hard hats. Many stopped at the store.

Most of the Glossers worked in the store, with forays. Sam, one of Louis’s sons and Stephen’s great-grandfather, tried joining the United States armed forces, but was rejected because of his blind left eye. When a Jewish Legion was organized in 1917 by Zionist leaders, Sam memorized the eye chart and enlisted to help the British seize Palestine. He traveled through the arid region, where Jews were setting up agricultural settlements. Sam started a friendship with David Ben-Gurion, the man who would later become the founding father of Israel. “Sam and Ben-Gurion stood guard duty together many times; according to family legend, they had been known to share a tent and became good friends,” Jeschonek wrote. While in the service Sam met Pearl, the Palestine-born daughter of Russian Zionists. Ben-Gurion was at their wedding in 1919. The couple sailed back to the US. Izzy—Stephen Miller’s maternal grandfather—was born three years later in Johnstown.

All their lives, the Glossers would strive to help the poor and persecuted. Louis donated relief for victims of pogroms back home. During the Depression, the Glossers left bags of free groceries on the doorsteps of the needy. Ruth wrote, “The misery, fear and economic deprivation of their earlier years were forever etched into their psyche. As a result, almost from the time of their arrival in the United States, and long before they had achieved financial stability they were already ‘giving something back’ . . . They had been on the receiving end of charity. And they never forgot this.” They abided by the Jewish tradition of tzedakah, from the Hebrew word “justice.” Unlike the Western concept of charity—to give out of a spontaneous desire to be kind—tzedakah is an ethical obligation to be just: to help the needy is to do what one must.

The family donated to an immigration organization, schools, hospitals, an orphans’ asylum and more in the Old World.

Stephen’s mom, Miriam, grew up in Glosser Bros., a playground for her and her siblings. In her testimony to Jeschonek, she described her childhood as “a great adventure.” She recalled “the wonderful aroma of hot roasted nuts that wafted through” the store. Her father, Izzy, had managed the toy department. At closing, Izzy would let Miriam and her siblings “raid the candy department.”

*

Miriam and her cousins grew up learning about their refugee roots. Before leaving for Columbia University, Miriam worked in the Glosser Bros. lingerie department, and learned all about “excellent customer service,” she told Jeschonek.

She delighted in entertaining people. She was in her high school pep club. She starred as the main character in at least one play. A photograph of Miriam in dramatics class shows her kneeling at the feet of her fellow students as they pretend to stone her. They were performing the classic Shirley Jackson short story “The Lottery.” It describes a fictional American small town where the residents are convinced that to survive, they must select someone to be the annual sacrifice. Miriam played the scapegoat. Mouth agape, pretty face in profile, she held an arm up to protect herself. The other hand lay at on the ground. She wore a skirt and a dark sweater. “It isn’t fair,” cried Miriam’s character in the short story. Her classmates seemed bored and distracted as they feigned killing her. One girl fixed her hair and stared at the camera. In the narrative by Shirley Jackson, the victim’s son participates. She screams, surrounded by her loved ones, “and then, they were upon her.”

*

Glosser Bros. expanded to operate in three states and was listed on the American Stock Exchange. But in the mid-eighties, the company began to experience cash flow problems. It had been made private through a leveraged buyout. After decades of success, it led for bankruptcy and was liquidated. “When they pulled out, they pulled the heart out of Johnstown,” says Jack Roscetti, a hairstylist and long-time resident who counted many Glossers among his customers.

The Glosser descendants spread out across the country. Ruth wrote, “Through the example of their lives [the Glossers] exemplified for their children and their children’s children the importance of the values of tzedakah, a caring, harmonious family life, a personal commitment to make the world a better place . . . It is indeed a precious legacy.” She concluded by listing the names of twenty-three families related to the Glossers who were killed in Antopol during the Holocaust. In 1924, as the eugenics movement gripped Americans with hatred of non-whites, legislation set quotas based on national origin, severely restricting the number of people who could come in from southern and eastern Europe, China, Italy, Japan and other areas. The Glossers’ home in the Old World was obliterated by the Nazis and nearly all two thousand inhabitants who had stayed were murdered. “By the time Antopol was liberated in June of 1944 only seven Jews were still alive to bear witness to the massacre,” wrote Ruth.

It was a memory the Glossers held on to, the memory of the annihilation. As Miriam raised Stephen and his siblings, it’s unlikely she knew that the lesson her mother had tried to keep alive—about the dangers of demonization, about the value of those who came to the United States in rags, penniless and illiterate—would come under direct assault by her son.

__________________________________

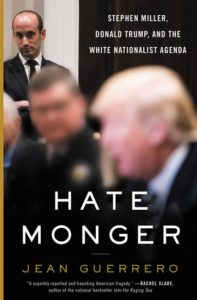

From Hatemonger by Jean Guerrero. Used with the permission of William Morrow. Copyright © 2020 by Jean Guerrero.