Frédéric Chopin in Exile: The Making of a Romantic

How Poland's November Uprising Inspired the Composers Best-Known Music

The decisive moment in Frédéric Chopin’s story, and that of Poland during the first half of the 19th century, came in 1830, when he was 20 years old and a spark of independence flew in Warsaw. The year before, Nicholas I of Russia had crowned himself King of Poland, disregarding the national constitution and parliament. The czar’s brother and factotum, Grand Duke Constantine, unleashed his secret police, abolished press freedoms, imposed taxes, closed Vilnius University, and deported Mickiewicz, the country’s most famous poet.

The final insult was a Russian scheme to use Poland’s army against the people of France to suppress their July Revolution, which deposed the last Bourbon monarch and put Louis Philippe—the “citizen king”—on the throne. On November 29th, 1830, a cadet at the Warsaw officers’ school led a group of co-conspirators in an attack on Constantine’s palace. The grand duke managed to escape (according to one historian he scurried off in women’s clothing), but the failed rebellion launched six months of unrest and turmoil.

Chopin had left Warsaw three weeks before the November Uprising for a European sojourn of music and adventure, traveling through Dresden, Vienna, Salzburg, and Munich, going to the opera and immersing himself in the local musical life. It being his first long-term trip abroad, a group of friends sent him off with a silver cup filled with earth they had collected in Żelazowa Wola, the small town where Chopin was born, thus allowing him to carry a bit of the beloved homeland away with him on his travels.

When the uprising began, Chopin’s friends rushed home to join the fight, but insisted he remain in exile and use his music to give voice to Poland’s struggle. Traveling the Continent, keeping in touch with friends and family through a regular stream of letters, he went to parties, dinners, plays, and operas. Then, as he wrote to a friend, he would return home around midnight, sit down, “play the piano, have a good cry, read, look at things, have a laugh, get into bed, blow out my candle and always dream about you all.”

Chopin was voiceless, homeless, and alone, “beyond ten frontiers” from friends and family, and to make matters worse his passport had expired.The November Uprising lasted less than a year, and in September 1831 the Russians brought the hammer down in Warsaw. From Stuttgart Chopin learned there was hand-to-hand fighting in the streets, including in the cemetery where his younger sister Emilia had been buried after suffering a massive tubercular hemorrhage at age 14. Being separated from his family was, for Chopin, a type of death. Only a month after he left home, he described himself as “a corpse” and began using the metaphor of the crypt to convey his melancholia. “Graves behind me and beneath me, everywhere,” he wrote to a friend; “a gloomy harmony arose within me.”

In Stuttgart, his separation anxiety developed into a morbid, fantastical obsession with death. He imagined his family butchered, the woman he loved in the hands of the Muscovites . . . “seizing her, strangling her, murdering, killing.” In his notebook Chopin wondered: “is a corpse any worse than I? A corpse . . . knows nothing of father, mother or sisters . . . it cannot speak its own language to those around it.”

He was voiceless, homeless, and alone, “beyond ten frontiers” from friends and family, and to make matters worse his passport had expired and there was no safe way back to Poland. Stuttgart was an abyss; “I pour out my grief on the piano,” he confided to his diary. It was during this time, as he faced his first Christmas alone, that he likely began composing the harrowing B-minor Scherzo op. 20, a work that begins with a piercing cry at the top of the keyboard followed by an anguished growl at the bottom.

It then proceeds on a frenzied, anxious journey until suddenly, and surprisingly, the music devolves into a melody known and loved by all Poles, the Christmas carol “Lulajże Jezuniu” (“Hush Little Jesus”), only to be rudely interrupted again by the tonal lacerations that began the piece. The scherzo concludes with the repetition, nine times in a row, of a single dissonant chord, a piece of musical language that always elicits in me the same tragic pain I experience when King Lear exclaims, over and over, the word Howl! after discovering the hanged body of Cordelia.

This early work contains Chopin’s musical signature: a collision of worlds fueled by the polar opposites of mood, tempo, melody, and emotional shadowing he would later deploy with such power in the funeral march of Opus 35. During this period he experimented in many genres, taking, for example, the mazurka, a lively, traditional Polish national dance, and reimagining it with startling rhythms and chromatically induced inner conflict. Leonard Bernstein loved these pieces, especially the op. 17, no. 4 Mazurka in A minor, because Chopin put him in “a bliss of ambiguities.”

In études, short practice pieces traditionally designed to explore different aspects of performance technique, Chopin experimented with tones, harmonies, and syncopations that would, a century later, become standard features of modern jazz. He also took a salon genre, the nocturne, and repurposed it.

An early example is the otherworldly op. 15, no. 3 in G minor, composed in the early years of the 1830s. It begins in one style, that of another Polish folk dance, the kujawiak, and then, after passing through a dark, sometimes jagged melody, he pauses, almost like a novelist reaching a chapter break, and changes the voice of the piece entirely, moving into a chorale, a form of plain chant one might hear in a church service. Then, before sending it off to his publisher, he slapped onto this strange-sounding work the label “Nocturne,” a brand-new genre pioneered by an English composer, John Field, which Chopin undertook to reinvent in his own voice and style.

These were startling creations, works that threw listeners into an unfamiliar musical landscape. For scholar Jim Samson it was this sojourn, far from home and with news trickling in week by week of the worsening situation in Poland, that saw Chopin’s now unmistakable tone journey from a post-Classical to a Romantic idiom. Responding to the turmoil at home, he “renovated” the old forms, mixing styles and bending genres, using a new kind of musical language to disrupt a listener’s expectations and tell a different kind of story.

Exiled from his homeland, wandering through Europe trying to decide where to settle, Chopin began developing the voice that would come to define his music deep into the future. He arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1831, just weeks after the uprising had been brutally put down, and virtually overnight became the poetic embodiment of “captive Poland.”

It would be just a few years later when the story of the failed revolution and Chopin’s poignant separation from family and friends crept into his writing and, without his planning it, formed the basis of what would become his most famous composition. For not only is a love of homeland deeply embedded in the funeral march; it’s where it all started.

The earliest clue in the composition story of Opus 35 turns up in an unlikely place: an auction house on Madison Avenue in New York City. It was a Tuesday in March 1969 when the Parke-Bernet Galleries held a sale of “Important Autographs and Manuscripts” that was noteworthy for its scope and variety: rare original documents spanning three centuries, authored by notable figures in politics, science, and the arts.

Virtually overnight Chopin became the poetic embodiment of “captive Poland.”Just a partial list includes Alexander Hamilton, Napoleon Bonaparte, Clarence Darrow, Henry David Thoreau, Queen Victoria, Washington Irving, Charles Dickens, John James Audubon, the abolitionist John Brown, items from 23 American presidents (including a letter from Thomas Jefferson stating “I am out of wine”), and a handwritten manuscript by John Steinbeck. Also included was a musical fragment in the hand of Frédéric Chopin, a manuscript consisting of just eight measures with no title except the notation Lento cantabile: an instruction to the performer to play slowly, in a singing style. (The word comes from the Italian verb cantare, to sing.)

It’s the melody of the Trio, the major-key lullaby that breaks up the two statements of the minor-key march—the music that so startled me when I first heard it in the Polish Consulate. This is the sweet, nocturne-like tune that invites you to forget, at least for a moment, the heavy, violent dirge that precedes and follows it.

Little is known about the Parke-Bernet fragment, which immediately disappeared into private hands after being acquired at the auction for $1,500, but the best guess of scholars is that Chopin inscribed the music into someone’s autograph album. These were popular in the 19th century: large, blank books bound in leather that friends (and the occasional celebrity) would “autograph” with a poem, drawing, musical sketch, or personal greeting. Some of these albums apparently had pages with music staves that made it easy to dash off short compositions, and Chopin was known to have inscribed his music into the albums of friends and admirers.

Once, for fellow composer Ignaz Moscheles, he wrote out eight measures from the celebrated refrain of the 17th Prelude from op. 28, popularly known as “Castle Clock” for the low A flat that is intoned 11 times in a row, like a tolling bell. The e’s something touching in this gesture: one great musician copying a famous lick for another. In the case of the Lento cantabile fragment there’s an intriguing clue about Chopin’s intentions, and reason to believe he attached great sentimental value to that lovely, portentous melody. It’s right there in the date near his signature, November 27th: the eve of the 1838 November Uprising in Warsaw six years earlier.

__________________________________

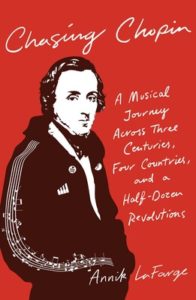

From Chasing Chopin: A Musical Journey Across Three Centuries, Four Countries, and a Half-Dozen Revolutions. Copyright © 2020 by Title TK Projects, LLC. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.