How Polar Explorer Ernest Shackleton Became an International Celebrity

Glorifying Disaster in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

“The fascinating thing about Mr. Shackleton’s report,” the New York Evening Globe commented one day after its publication on March 24, 1909, “is the story of the struggle rather than the results of the struggle. All of us feel loftier in our inner stature as we read how men like ourselves pushed on until the last biscuit was gone.” At the dawn of the 20th century, after the rise of industrialized technologies that promised to make all results possible and before the Great War that made even the most self-sacrificing human struggle seem meaningless while, at the same time, tarnishing technology’s gleam, the Globe’s comment captured the essence of heroism as extraordinary efforts by ordinary people.

Ernest Shackleton had an advance contract with a leading newspaper for an exclusive first report on his expedition—income from the contract helped to finance his efforts. For newspapers—then at the height of the publishing wars that marked the era in journalism—disasters, battles, and harrowing expeditions sold best. Publishers paid top dollar for exclusive accounts. On March 22, the Nimrod stopped for a day at Steward Island, just south of New Zealand, where a special telegraph operator waited to dispatch Shackleton’s report to London’s Daily Mail.

*

A master storyteller and a family man with a gift for attracting women and befriending men, Shackleton knew what the public wanted and, in his report for the Daily Mail, dished it out in due measure. Newly discovered mountains and the world’s largest glacier; waist-deep snow with crevasses that swallowed ponies and left men hanging by their harnesses; man-hauling 500-pound sledges over blue ice; and struggle, always struggle, filled this first narrative. “For sixty hours,” he wrote at one point, “the blizzard raged, with 72 degrees of frost and the wind blowing at seventy miles per hour. It was impossible to move. The members of the party were frequently frostbitten in their sleeping-bags.” The race to survive ran through the account, underscored by the repeated refrain “food had again run out.” These were Shackleton’s own words. The ghostwriter who helped transform his sledging diary and this first narrative into a bestselling book, In the Heart of the Antarctic, would not join him until New Zealand.

To capitalize on its investment, the Daily Mail solicited dozens of celebrity endorsements for Shackleton’s feat, which it published along with the queen’s “very hearty congratulations,” though her telegram mistakenly credited Shackleton with hoisting her flag at the magnetic pole. Mountaineer Martin Conway hailed the ascent of Mount Erebus as “a great achievement,” while Albert Markham of former farthest-north fame called the polar trek “a wonderful performance.” Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, and Robert Scott added their tributes, though for personal reasons each was pleased that Shackleton had fallen short of the pole. By the time his first report had circled the globe, Shackleton had stepped out of Scott’s shadow and into the limelight of worldwide fame.

“For newspapers—then at the height of the publishing wars that marked the era in journalism—disasters, battles, and harrowing expeditions sold best.“

After the humiliation of the Boer War and with the rising German challenge to its military superiority, the British Empire needed heroes, and Shackleton seamlessly fit the bill. First in New Zealand, then in Australia, and finally in England, he was cheered by the masses and feted by the elites in the upstairs-downstairs Edwardian swirl. “I am representing 400 million British subjects,” Shackleton said before his departure, and upon his return, they all seemed to adopt him.

It was the struggle more than the results that won plaudits. “An amount of pluck and determination has been displayed by Lieut. Shackleton and his companions which has never been surpassed in the history of Polar enterprise,” the Royal Geographical Society proclaimed. The Standard spoke of his “intrepid heroism,” the Morning Post of his “extraordinary endurance.” “The benefit,” the Spectator said of Shackleton’s expedition, “is to be seen in the proof it gives that we are not worse than our forefathers; that the blood of the Franklins, the Parrys, and the Rosses still flows in a later generation; and that men of the various ranks and various callings are still found ready to encounter great risks and endure prolonged privation and suffering for no gain to themselves beyond the joy of mastering difficulties.” A knighthood followed. It scarcely mattered that Shackleton had failed to reach the pole. “His adventures,” the Nation observed, “appear to have been brilliant, if not extremely valuable.”

Shackleton wanted to go back as soon as possible to finish the job. He discussed it with Frank Wild during the grueling return march and received Wild’s commitment to return. The fame, money, lectures, and elite social invitations only made him want to go more. “The world was pleased with our work, and it seemed as if nothing but happiness could enter life again,” Shackleton wrote with some candor, but he recognized the fleeting nature of celebrity and knew that it needed feeding by new fame.

Seeking new feats in the Antarctic before interest waned, Shackleton planned the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition for 1914–16. The ambitious plan involved sending a support party to the old British huts on Ross Island to lay resupply depots as far as the Beardmore Glacier while he took the main party to the Weddell Sea, from which he would march across the continent to the Ross Sea. The Ross Island party was stranded at Scott’s old huts when its ship drifted out to sea in a gale, however, and Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, was icebound and crushed before reaching the Weddell Sea coast.

These setbacks provided the path to lasting glory for Shackleton, whose leadership skills always rose in crisis situations. With an air of confidence that masked his own fears, Shackleton led his men on a storied five-month journey across drifting sea ice and by lifeboats to Elephant Island. From there, Shackleton and five others sailed 800 miles across the notoriously turbulent Southern Ocean by open boat to a whaling station on South Georgia Island. The leadership displayed by Shackleton during this epic trek and open-boat voyage was much like that shown by him on the Nimrod Expedition’s southern journey, writ large for everyone to see. Yet there was more. On the fourth attempt, in the teeth of midwinter storms, he rescued all his men on Elephant Island and turned his attention to the Ross Sea sector, where three had already died. But after joining the imperial effort to rescue the survivors, Shackleton returned to an England consumed with the bloodiest war of its history. Amid the Great War, no one much cared about polar heroics. Lasting fame for the Endurance Expedition came too late for Shackleton to enjoy. Following World War I, he tried one last time for Antarctic glory with an expedition in 1921–22, but died at the age of 47 from a heart attack on South Georgia Island. Rather than bring his body back to England for a hero’s funeral, Shackleton’s wife, Emily, asked that it be buried on South Georgia near his beloved Antarctic. The tombstone bears Shackleton’s favorite words, drawn from the poet Robert Browning, that a man should strive “to the uttermost for his life’s set prize.”

__________________________________

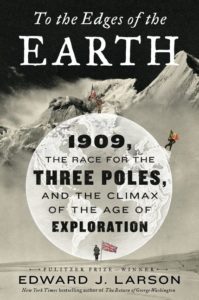

From To the Edges of the Earth. Used with permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2018 by Edward J. Larson.

Edward J. Larson

Edward J. Larson is the author of many acclaimed works of history, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning account of the Scopes trial, Summer for the Gods, and the recent study of liberty and slavery at the founding, American Inheritance. A chaired professor of history and law at Pepperdine University, Larson lives with his family near Los Angeles.