This essay owes a great debt to Angela Bourke’s essential biography,

Maeve Brennan: Homesick at The New Yorker (Jonathan Cape, 2004)

Yesterday afternoon, as I walked along Forty-second Street directly across from Bryant Park, I saw a three-cornered shadow on the pavement in the angle where two walls meet. I didn’t step on the shadow, but I stood a minute in the thin winter sunlight and looked at it. I recognized it at once. It was exactly the same shadow that used to fall on the cement part of our garden in Dublin, more than fifty-five years ago.

Here is Maeve Brennan hanging on, recording a solitary encounter in her last published piece in The New Yorker. On the sidewalk of the city where she had come to live in her twenties and spent the rest of her life, she recognizes, that sunny winter’s day in 1981, the stamp of the house in Dublin where she had passed her childhood. Maeve Brennan and her work had already been lost to public view when she died in 1993. Never eager to establish a home, moving from one rented room to another, staying in friends’ places while they were away, she disappeared by degrees, at last joining the ranks of the homeless. But four years after her death, with the publication of The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin, her work appeared in a new edition. For the first time the Irish stories could be read in a sequence that made strikingly clear the remarkable depth and originality of her art.

An exile whose imagination never abandoned its native ground, Maeve Brennan was in perpetual transit. Her emigration was not chosen, although in time it became so. She would not have left Ireland at the age of 17 if she’d been given the choice, and yet in her adult years she didn’t choose to return. A displaced person, always on provisional ground. When writing about New York City she described herself as a “traveler in residence.” She was staying for a while, poised to depart. And in that displacement she may be a figure for the Irish American a little disoriented as to notions of home, or for any immigrant who finds herself elsewhere without having chosen to leave where she came from. In time, Maeve Brennan’s status as traveler had become a habit, a preference, an identity. But at one time there had been a home, a fixed address at 48 Cherryfield Avenue. Lost, it could only be remembered.

The particulars of Maeve’s wandering life were often elusive, even to her friends. But in her art, for which she sacrificed so much, she is everywhere felt in her dedication to the poetry of place, whether in Dublin or New York. It is in her work we find her.

*

In June 1948, Maeve’s father wrote to her from Ireland referring to the recent visit she’d made to see her parents not long after their return from his ambassadorship in DC. By then, she’d lived for five years in New York City, working briefly at the public library on 42nd Street before being hired at Harper’s Bazaar in 1943 by the editor Carmel Snow, also Irish. There she’d been drawn into a world that included writers and editors, some at Harper’s and others, like Brendan Gill, at The New Yorker. She frequented Tim and Joe Costello’s, at 44th and Third Avenue, a favorite drinking and eating place for Irish writers, and increasingly writers of any stripe. As a young man Tim Costello had known her father as a fellow Republican in Dublin, and he now kept an eye out for her. While she’d adopted many aspects of American fashion and culture, her speaking voice remained the one she’d grown up with. She was “effortlessly witty,” as William Maxwell wrote of her later, had a lively sense of the ridiculous. She was generous, sometimes extravagantly so, bestowing lavish gifts, pressing on friends things of her own they admired. Costello’s was only a few blocks away from The New Yorker, and on the basis of a few short pieces she’d written for that magazine she was hired there by William Shawn, in 1949, at Brendan Gill’s urging.

But during those years at Harper’s she began and completed a novella, The Visitor, that was only discovered years later, in 1997, in the library of the University of Notre Dame among the papers of Maisie Ward—of Sheed and Ward—who with her husband had founded a Catholic publishing house in London that had moved to New York. The manuscript can be dated by the address—5 East Tenth Street—written on its cover sheet. Brennan was living there in 1944, when she was 27 and working at Harper’s. By the late 1940s she’d moved. Maisie Ward must have read the manuscript or at least received it. But who else? And why was it never published? Did Brennan, who sometimes worked on a story for decades, never revisit it? Did she keep a copy herself? This novella announces her great themes and obsessions, and who can say but that she herself was shy of it.

“The particulars of Maeve’s wandering life were often elusive, even to her friends. But in her art, for which she sacrificed so much, she is everywhere felt in her dedication to the poetry of place, whether in Dublin or New York.”

With The Visitor, the harrowing novella that seems to have been Maeve Brennan’s first completed work, the reader, with a jolt of recognition, enters a world that is at once new and strangely familiar. How simple the writing, evoking the crowded but lonely mood of a train arriving in Dublin on a rainy November evening. And then, seamlessly, the story opens, and we’re in a place known better in dreams, in the murkier places of the unconscious. “Home is a place in the mind. When it is empty, it frets. It is fretful with memory, faces and places and times gone by. Beloved images rise up in disobedience and make a mirror for emptiness. Then what resentful wonder, and what half-aimless self-seeking. . . Comical and hopeless, the long gaze back is always turned inward.”

In 1949, the following year, Maeve was hired by The New Yorker, and her life changed again. While Harper’s had been a woman’s world—run by a woman who hired other women—The New Yorker, arguably the most powerful literary magazine in America at the time, was a magazine dominated by men. As elsewhere during the 1950s, a woman’s value—however that might be assessed—would have been assumed to be different from a man’s. In her early thirties Maeve wore her thick auburn hair in a ponytail that made her look younger than she was. Later she piled it on her head. Just a little over five feet, she wore high heels, usually dressed in black, a fresh flower, often a white rose, pinned to her lapel, a bright dash of red lipstick across her mouth. Several of her colleagues would become good and constant friends—Joseph Mitchell, Charles Addams, Philip Hamburger, and, of course, William Maxwell—and some lovers as well. But she was an outsider, a stylish and beautiful Irish woman in a world of American men. As Roger Angell put it, “She wasn’t one of us—she was one of her.” Although she would live in an assortment of furnished rented rooms and hotels in Manhattan—and as the years went by, increasingly obscure ones—her place at The New Yorker, however alien at first, provided a kind of sanctuary where her work would be fostered and edited and published.

Early in 1954 Brennan began writing the unsigned pieces for the “Talk of the Town” in the voice of “the long-winded lady.” They would appear in the magazine for more than 15 years, but only in 1968 would the writer be identified as Maeve Brennan when she chose some of her favorites to be published as a selection. In a foreword Brennan describes her persona:

If she has a title, it is one held by many others, that of a traveler in residence. She is drawn to what she recognized, or half-recognized, and these forty-seven pieces are the record of forty-seven moments of recognition. Somebody said, “We are real only in moments of kindness.” Moments of kindness, moments of recognition—if there is a difference it is a faint one. I think the long-winded lady is real when she writes, here, about some of the sights she saw in the city she loves.

Indeed, she declares her love for the city in an ode to the ailanthus, New York City’s backyard tree, that appears like a ghost, like a shade, beyond the vacancy left by the old brownstone houses speaking of survival and of ordinary things: “New York does nothing for those of us who are inclined to love her except implant in our hearts a homesickness that baffles us until we go away from her, and then we realize why we are restless. At home or away, we are homesick for New York not because New York used to be better and not because she used to be worse but because the city holds us and we don’t know why.”

When Brennan was 37 she married St. Clair McKelway and joined him where he lived in Sneden’s Landing, a community just north of the city on the west bank of the Hudson. He worked at The New Yorker as a nonfiction staff writer, was three times divorced and 12 years older than herself, and known to be a compulsive womanizer. Like Brennan, he was volatile, hard-drinking. And like her too, incapable of handling money. “I think I feel as Goldsmith must have done,” Maeve wrote to Maxwell, “that any money I get is spending money, and the grown-ups ought to pay the big ugly bills.” During the three years she was married, her mother died, a death she grieved for a long time, and she and St. Clair fell into calamitous debt. Her stories from that period are often set in Herbert’s Retreat, as she calls Sneden’s Landing: unlike the Dublin stories, they tend to be ironic, even brittle, in tone; they have to do with affluent households looked after by knowing Irish maids who observe and appraise their employers’ lives from the kitchen.

And on St. Patrick’s Day, 1959, Brennan wrote a reply to a letter from a reader asking when more Herbert’s Retreat stories would appear in The New Yorker, a letter that was making the rounds in the office. When it reached her, she wrote a reply on the back before passing it on.

I am terribly sorry to have to be the first to tell you that our poor Miss Brennan died. We have her head here in the office, at the top of the stairs, where she was always to be found, smiling right and left and drinking water out of her own little paper cup. She shot herself in the back with the aid of a small handmirror at the foot of the main altar in St. Patrick’s cathedral one Shrove Tuesday. Frank O’Connor was where he usually is in the afternoons, sitting in a confession box pretending to be a priest and giving a penance to some old woman and he heard the shot and he ran out and saw our poor late author stretched out flat and he picked her up and slipped her in the poor box. She was very small. He said she went in easy. Imagine the feelings of the young curate who unlocked the box that same evening and found the deceased curled up in what appeared to be and later turned out truly to be her final slumber. It took six strong parish priests to get her out of the box and then they called us and we all went and got her and carried her back here on the door of her office. . . We will never know why she did what she did (shooting herself) but we think it was because she was drunk and heartsick. She was a very fine person, a very real person, two feet, hands, everything. But it is too late to do much about that.

It was only after she had amicably separated from St. Clair during the winter of 1959 and was alone once more that Brennan returned to the Dublin stories she’d been working on during the years leading up to her marriage. The solitary life had fostered her writing earlier, and now she would again live by herself, accompanied by her beloved black Labrador retriever, Bluebell. During the early 1960s when Brennan was writing steadily, she spent the summers in the city and the winters alone in East Hampton, renting houses off-season close to her devoted and nurturing friends Sara and Gerald Murphy, on whom F. Scott Fitzgerald in Tender Is the Night had modeled Dick and Nicole Divers. She wrote about the sea and shore and seagulls, and about children too. She wrote about the progress of the day as seen through the eyes of her animals—her cats and Bluebell—with the radiant simplicity of Colette.

But most of all she continued to work on the stories for which she is remembered, the Derdon stories, to publish them, and began to write about the Bagots. What she required, it seemed, was a room where she could be alone with her typewriter.

“She had unequivocally become an outsider now, one of the poor and afflicted among whom she’d always counted the visionaries.”

She would go on writing of lonely marriages as lived out in the house at 48 Cherryfield she’d grown up in. And though by this time she’d had her own intimate experience of marriage, and there are many echoes of her parents’ lives in the stories, her portraits are originals. Both couples—Hubert and Rose Derdon and later on Martin and Delia Bagot—are shadowed by fear and regret and shame. They experience self-misgivings, a ravished sense of having made some first mistake, of having missed out on some crucial knowledge that everyone but themselves has grasped and so are condemned to solitude.

Brennan’s first collection, In and Out of Never Never Land, was published by Scribner’s in 1969 and included the Bagot and the Derdon stories that had been published up to that point. It included neither “The Springs of Affection” nor “Family Walls,” two of her greatest stories, which would appear in The New Yorker only three years later. In 1974, another collection, Christmas Eve, was also published by Scribner’s that included these newer stories as well as several from the 1950s. There was no paperback edition of either one. And as she had no Irish publisher, her Dublin stories went largely unnoticed in Ireland where so many of them were set. At about this time William Maxwell said he thought her the best living Irish writer of fiction, but in her own country she was almost entirely unknown.

By the early 1970s Brennan’s friends had become aware of painful changes in her behavior. She was no longer a young woman in a working world still dominated by men: she was middle-aged now and alone. Her father and Gerald Murphy had died within a few weeks of each other in the fall of 1964, and her nearest companion, Bluebell, was also dead. She was having trouble writing. Pursued by an accumulation of debts and creditors, she stayed in increasingly rundown hotels. She had always moved from place to place, but now she began moving rapidly, as her father had done long ago when he was on the run and staying in safe houses during the Irish Rebellion. Sometimes she camped out—like a similarly bereft Bartleby—in the offices where she worked: in the New Yorker offices in a little space next to the ladies’ room, at one point tending a wounded pigeon. Then she had a severe breakdown and was in the hospital for a time. When things were better she returned to Ireland, thinking perhaps to remain there. But it must have been too late. For a few weeks she stayed with her cousin Ita Bolger Doyle. She wrote to William Maxwell from the garden studio on September 11, 1973:

The typewriter is here in the room with me—I hold on to it as the sensible sailor holds on to his compass. . . What I am conscious of, is of having the sense of true perspective. . . that is in fact only the consciousness of impending, imminent revelation. “I can see.” But “I can see” is not to say ‘I see.’ I don’t believe at all in revelations—but to have, even for a minute, the sense of impending revelation, that is being alive.

Sometime after her return to New York from Ireland, things again fell apart; her movements became increasingly hard to track. She’d always been known for her generosity; now she began rapidly to divest, handing out money in the street. She was occasionally seen by her old colleagues sitting around Rockefeller Center with the destitute. Then she fell out of the public eye altogether. She had unequivocally become an outsider now, one of the poor and afflicted among whom she’d always counted the visionaries. It wasn’t until she seemed quite forgotten—until after her death in 1993 in a nursing home in Queens where she wasn’t known to be a writer—that she again swam into view.

Christopher Carduff, a senior editor at Houghton Mifflin at the time, encountering Brennan’s work by chance in the late 1980s, “fell in love,” as he put it, and undertook to get it all in print, including the recently discovered novella The Visitor. In 1997, for the first time, the Derdon stories as well as the Bagot stories could be read in sequence when they appeared in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin. William Maxwell wrote a foreword to the volume. One of the many writers who greeted the publication was Mavis Gallant: “How and why the voice of these Dublin stories was ever allowed to drift out of earshot is one of the literary puzzles. Now The Springs of Affection brings it back, as a favor to us all, and it is as true and as haunting as before.”

One of the literary puzzles indeed: Perhaps her colleagues and friends at The New Yorker tried and failed to intervene on her stories’ behalf when Brennan was unable to do so herself? To help see her existing volumes into paperback? Or press for the Dublin stories to be compiled and arranged, as did Christopher Carduff? Would things have been different if she had been “one of us”? A man rather than a woman, a compatriot? Unknowable and complex factors, surely, must have played their part, but it’s painful to remember that Brennan’s furious dedication to her art had been witnessed by so many.

__________________________________

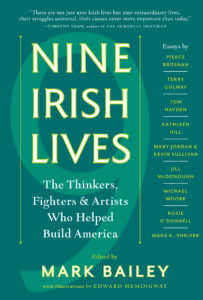

From Nine Irish Lives. Used with permission of Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2018 by Kathleen Hill.