How New York City Ended Up With a Giant, Beautiful Park

On the Citizen-Driven Origins of Central Park

Disappointed but not discouraged by the lack of support for the notion of a group of citizens forming a partnership with city government for the purpose of restoring and maintaining Central Park, I remembered that it was in fact a group of citizens who had advocated the creation of Central Park in the first place.

*

First Proponents

In 1844 poet and newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant encouraged the establishment of the kind of park that would satisfy the ambitions of civic-minded New Yorkers who wished their burgeoning metropolis to emulate great European cities in this regard. Yet, unlike the Old World parks, which had their origins as the domains of kings and princes, and in spite of the fact that some proponents were initially uneasy over the proposed admission of the hoi polloi, the New York park was intended to be a people’s park open to all classes of society. In promoting this democratic objective, Bryant suggested that the forested area known as Jones Wood, a 154-acre parcel bounded by 66th and 75th Streets between Third Avenue and the East River, would make an ideal location. Featuring rocky outcroppings and sparkling streams, Jones Wood was already a de facto park, a popular haunt for botanists, picnickers, and seekers of solitude. “Nothing is wanting,” he wrote, “but to cut winding paths through it, leaving the woods as they now are and introducing here and there a jet from the Croton Aqueduct, the streams from which would make their own waterfalls over the rocks, and keep the brooks running through the place always fresh and full.”

On the heels of Bryant’s advocacy, after returning from a trip to England in 1850, Hudson River Valley nurseryman–turned–landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852) also proposed the creation of a public park worthy of the citizenry of a metropolis-in-the-making. In his magazine The Horticulturist, Downing touched the tender nerve of his American readers’ cultural inferiority complex with these words: “What are called parks in New York are not even apologies for the thing; they are only squares or paddocks.” A year later outspoken newspaper editor, politician, and social reformer Horace Greeley announced in his New-York Tribune: “The parks, squares and public gardens of London beat us clear out of sight.”

Legislative Debate

Spurred by such publicity, the popularity of the park cause grew among civic-minded New Yorkers, becoming a political issue in the mayoral campaign of 1850. Both candidates endorsed it, and in 1851 the winner, Ambrose C. Kingsland, issued a message to the Common Council calling for “the purchase and laying out of a park, on a scale which will be worthy of the city.” With the concurrence of the council, a bill was sent to Albany recommending Jones Wood as the most desirable site for a new park, and on July 11, 1851, legislation authorizing the taking of that property was passed.

Aghast that potentially valuable commercial water frontage would be set aside for a non-economic use, business interests sought to have the bill rescinded. The park’s champions responded with an alternate suggestion: a larger park on another site. Indeed, Downing thought Jones Wood ridiculously small to meet New York’s future recreational needs. “It is only a child’s playground!” he cried. “500 acres is the smallest area that should be reserved for the future wants of such a city, now, while it may be obtained.” While Bryant felt that the beauties and waterfront location of Jones Wood made it a particularly apt choice for a park, he did not believe that it was the only suitable location; in fact, he thought it would be a fine idea if the public were to gain both Jones Wood and an additional property known as “the central reservation.” Stretching northward from 59th Street for nearly two and a half miles, the reservation encompassed the land that had been set aside for the construction of an additional reservoir within the midpoint of the system of basins built to hold water from the recently constructed Croton Aqueduct.

“Unlike the Old World parks, which had their origins as the domains of kings and princes . . . the New York park was intended to be a people’s park open to all classes of society.”

A select committee of the state senate was appointed to consider the comparative merits of the two locations. Expert testimony was collected. The botanist John Torrey, who had frequented Jones Wood since boyhood, told the committee of its “fine specimens of oaks, tulip trees, liquidambar, hickories, birch, and some cedars,” and he said he preferred Jones Wood to the “more bald and unpicturesque” central site. Others who appeared before the committee remarked on its rocky barrenness, since many trees in the southern half of the park had been cut down for firewood and those in the center removed to make room for a receiving reservoir when the Croton Aqueduct system of water distribution had been built ten years earlier. However, it was agreed that with a large expenditure for draining, topsoil, and tree planting, the land around the planned reservoir could become a park. Furthermore, it would increase the value of property surrounding it. After weighing what it had heard, the committee recommended that both parks be acquired, but urged that Jones Wood be developed first, since its landscape attractions were immediate rather than long-range. With humane pragmatism, the authors of the report summarizing the committee’s findings argued:

The panting and crowded families of the less wealthy, whose children fill the bills of mortality, are entitled to ask, what has posterity done for us? Why should they be taxed now to plant groves, which 70 years hence may shelter those who come after them, when health and pure air, wafted from the breezy river, through ample shades, are within their present grasp?

The passage of the 1851 bill by the state legislature in Albany authorizing the acquisition of Jones Wood and the counterproposal to acquire a larger site in the center of Manhattan resulted in the creation of a special committee of the city’s board of aldermen, to study their respective merits with regard to “Extent, Convenience of Locality, Availability, and Probable Cost.” respective merits with regard to “Extent, Convenience of Locality, Availability, and Probable Cost.”

In their January 2, 1852, “Report Relative to Laying Out a New Park in the Upper Part of the City,” the committee members foresightedly argued that “Central Park would probably be one of the largest city parks in the world, but not too large for the use of a city destined, in all probability, to exceed in population every other,” thereby concluding that “the proposition of Central Park is greatly to be preferred.” In addition to its greater size compared with Jones Wood, Central Park’s long and narrow rectilinear shape was no defect in their eyes, since such a park “was capable from its extent, of being laid out in a very great length of serpentine road, which a judicious engineer can so contrive as not only to produce startling effects of the distant landscape, and also bring the peculiar natural and artificial beauties of the place into the best points of view, but at the same time, to turn and wind this road through the place, so as to allow a very long drive through constantly varied scenery.”

Being in the middle of Manhattan rather than on the waterfront, like Jones Wood, was a further asset in their eyes, inasmuch as Central Park would be surrounded on all sides by Manhattan’s street grid and therefore have multiple points of access from four sides when the platted streets were constructed, whereas Jones Wood was a half-mile-square parcel with single-side accessibility in an out-of-the way locality that would necessarily be bisected by the construction of Second Avenue. Moreover, they maintained that the proposed alternative site was not deficient in scenic potential, being “so diversified in surface, abounding so much in hill and dale, and intersected by so many natural streams.” They thought as well that the location within its precincts of the reservoir that was part of the recently constructed Croton Aqueduct’s distribution system, far from being an obstacle, was an asset because it would provide an unlimited supply of water for artificial lakes and fountains within the park. Capping their argument in its favor, they noted that since the tops of the large outcrops of Manhattan schist were elevated above the surrounding landscape, they would be able to serve as platforms from which to gain magnificent views in all directions.

The committee reasoned that, whereas thinning many of the venerable trees of Jones Wood would be necessary to create a park, “Central Park will be furnished, of course, with a very choice assortment and great variety of new trees, much more ornamental, and casting more agreeable shade than the natural forest trees, [and] besides, a proper variety of park scenery requires that certain large portions should be improved as sloping lawns, or mounds for statuary and monuments, and points of view for distant landscapes—all of which allow no trees whatsoever.”

Acting on the report, the state legislature in 1853 passed two bills, one authorizing the designation of Jones Wood as future parkland, and the other the acquisition of 760 acres extending from 59th to 106th Streets between Fifth and Eighth Avenues (subsequently increased to 843 acres when the northern park boundary was extended to 110th Street). A board of commissioners, along with an advisory board chaired by Washington Irving, was established to oversee the design and development of the park. A civil engineer, Egbert Viele (1825–1902), made a topographical survey of the site and a general plan for its development in the hope that he could eventually receive “compensation suitable to the time and skill . . . expended on the work.” Since the clearance of the site was already under way, candidates were interviewed for the position of superintendent of the land-clearing operations that had begun under Viele’s direction. They included 36-year-old Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903), a farmer-turned-journalist-turned-author-and-publisher.

__________________________________

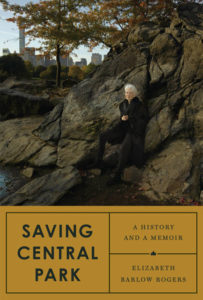

From Saving Central Park: A History and a Memoir. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers.

Elizabeth Barlow Rogers

Elizabeth Barlow Rogers is the president of the Foundation for Landscape Studies and the author of several books, most recently Saving Central Park. She has long been involved in historic landscape preservation and was the first person to hold the title of Central Park administrator, a position created in 1979. In 1980, she was instrumental in founding the Central Park Conservancy, a public-private partnership supporting the restoration and management of the park. She served in both positions until 1996. A native of San Antonio, Texas, she has made New York her home since 1964.